A scene from the play. All photographs from Lusk, Wyoming, July 2019, by Balazs Gardi for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

Every year in Lusk, Wyoming, during the second week of July, locals gather to reenact a day in 1849 when members of a nearby band of Sioux are said to have skinned a white man alive. None of the actors are Native American. The white participants dress up like Indians and redden their skin with body paint made from iron ore.

The town prepares all year, and the performance, The Legend of Rawhide, has a cast and crew of hundreds, almost all local volunteers, including elementary school children. There are six generations of Rawhide actors in one family; three or four generations seems to be the average. The show is performed twice, on Friday and Saturday night.

Dan Henry Hanson in the role of the Indian Chief during a performance of The Legend of Rawhide. All photographs from Lusk, Wyoming, July 2019, by Balazs Gardi for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

The plot is based on an event that, as local legend has it, occurred fifteen miles south of Lusk, in Rawhide Buttes. It goes like this: Clyde Pickett is traveling with a wagon train to California. He tells the other Pioneers: “The only good Injun’s a dead Injun.” Clyde loves Kate Farley, and to impress her, he shoots the first Indian he sees, who happens to be an Indian Princess. The Indians approach the Pioneers and ask that the murderer give himself up. Clyde won’t admit he did it. The Indians attack the wagon train and, eventually, Clyde surrenders. The Indians tie Clyde to the Skinning Tree and flay him alive. Later, Kate retrieves her dead lover’s body and the wagon train continues west.

At the Friday show, the man who plays Clyde is blood-soaked and a little embarrassed. He let a smile slip during the skinning scene. He must have been thinking about something else, he tells me later. The man’s name is Weldon Tschacher, and when he’s not playing Clyde he works at an auto shop. He lives about ten minutes away, in Manville. When I ask what it means to him to play the role of the white man getting skinned alive by Indians, he says he’s never really thought about it. Rawhide, he tells me, is “pretty much a history of this territory. Just a history.” But aside from a few trace mentions in old frontier journals, there is no historical evidence that the Rawhide story is true. “Like many legends,” wrote James E. Potter, a research historian for the Nebraska State Historical Society, the Rawhide tale “achieved believability through frequent repetition, publication, and testimony, by persons who claimed to know the facts.”

Lusk is a desolate place, a high-plains town of about fifteen hundred people in Niobrara County, the least populous county in Wyoming, America’s least populous state. The town was once a trading center for ranching, dry farming, and oil production. An outdated electromechanical switch in the local telephone system meant that residents could not make direct international phone calls until 1993. The closest big city is Denver, a four-hour drive away. Cheyenne, the capital, is more than a hundred miles south. Lost Springs, population four, is right up the road.

In July, when I arrive, the air is sweet with the smell of clover and pine, and the sky is a pale dome. Downtown Lusk is made up of a scattering of low buildings on Main Street—the Family Dollar, the Silver Dollar Bar, Lickety Stitch Quilts, Lusk Game Processing—all of it quite diminutive in the vast prairie. Lusk feels less like a place to live than a monument to the frontier. The town is surrounded by the former routes of white settlers: the Oregon Trail, the Mormon Pioneer Trail, and the California Trail. Tourism sites in and around Lusk celebrate obsessively preserved Western origin stories. There are wagons everywhere: in the parking lot of the Best Western, on the roof of the Covered Wagon Motel, along Main Street, and in the yard of the Stagecoach Museum. At the Spirits Liquor Lounge, where the cowboys who play Indians in Rawhide like to drink after rehearsal, the walls showcase framed jigsaw puzzles that depict famous Native American chiefs. Ten miles south, off the old Cheyenne–Deadwood stagecoach route, is one of the few monuments in the country that is dedicated to a saloon’s madam.

The Rawhide performance is staged at the Niobrara County Fairgrounds, an easy walk from Main Street. The grounds are small, consisting of a rodeo arena, a livestock barn, and a community building, all surrounded by about two acres of green pasture. It’s the day before the first performance, and the arena has been transformed into a theater; bleachers overlook the dirt stage. On one side of the stage is what the script calls the “Indian Village,” which includes the Skinning Tree and three large canvas tepees that are painted with colorful symbols. On the other side, there is a forest of pine trees—real trees—next to Styrofoam boulders and a fishing hole. Behind the stage is a small hill. This is where the Indians perform their attack on the Pioneers.

All day Thursday before the dress rehearsal, RVs, horse trailers, pickup trucks, and covered wagons drive over to the pasture adjacent to the arena, where horses are feeding on grass. Residents claim that visitors from Germany, Norway, and Italy have attended the show. Today I see no foreigners, only people who seem like they’re from the same county and voted for the same president. I meet five or six residents who have played Clyde, including Dean Nelson, who met his wife on the set of Rawhide. She was playing Kate opposite his Clyde. They had a mock wedding in the arena. A few years ago, a man proposed to Dean’s niece on set.

Dean shows me the Skinning Tree, which is dead and leafless. “It’s the only tree we use, year after year,” Dean says. Decades worth of fake blood darkens the trunk. The performers use a mixture of red food dye and Ivory soap for blood; they paint Clyde with it, cover him with a type of tape to mimic skin, and peel it off to reveal the blood.

Dean’s mother, Holly, is observing us from nearby. She wanders over and introduces herself. She is a volunteer cook for the cast and crew and tonight she’s making enough beef noodles to feed everyone—about three hundred people. Holly has light red hair and small glasses. She’s a retired elementary school teacher who wrote her own third grade textbook, Niobrara County History, which begins with the primordial seas and ends with photos of crumbling frontier sites. It’s about twenty pages long, printed on computer paper and held together with a plastic spiral binding. The book includes a few brief mentions of Native Americans of the Plains, but it skips over their destruction, and jumps to when Wyoming became a state on July 10, 1890. Page thirteen memorializes George Lathrop—“Pioneer of the West, Indian Fighter, Veteran Stage Driver”—who played the role of Indian Chief in the Fifties.

“I get goose bumps when the wagon train comes around the hill,” Holly says. “It just gives you the chills. Then you see the Indians, from one side to the other side. Well, they don’t like to be called ‘Indians.’ But the reason we don’t have any real Indians in the roles is because there aren’t any in this county.”?*

I first heard about Lusk from a man who was from eastern Wyoming. He mentioned Rawhide after a mutual friend told us a story about a dream his girlfriend had. He recounted how she would wake up in the middle of the night and there would be a Native American man with long black hair standing next to her. He taught her things, medicinal things, and he also wouldn’t leave her alone, even when she asked him to go. The only way to get rid of him was to throw him in a river. The dream and its telling were not subtle in their colonialist perspective, and both exemplified the ways that non-Natives think and talk about Natives. In this case, the Native is fetishized, exotic, and mysterious; he is extinct but able to be used when desired, and then discarded.

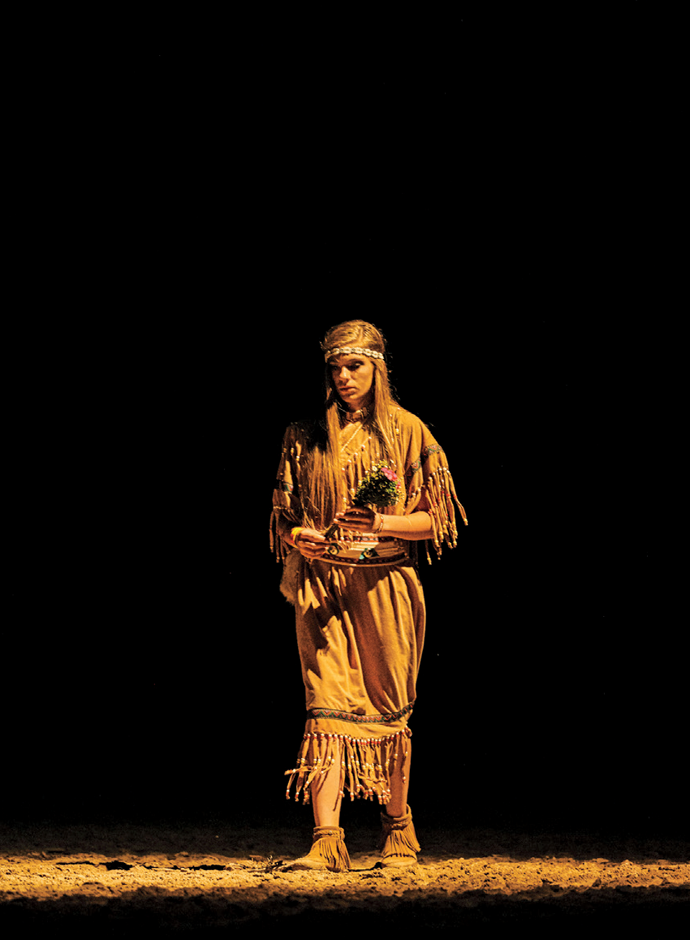

Courtney Rowley in the role of the Indian Princess

If you grew up white in America, you probably either played Indian or were witness to it in some way. Philip Deloria, a history professor at Harvard and author of the book Playing Indian, argues that white Americans have always articulated their identity through Indianness. In each historical moment, he writes, “Americans have returned to the Indian, reinterpreting the intuitive dilemmas surrounding Indianness to meet the circumstances of their times.”

Colonists throughout history often exaggerated the differences between themselves and the people they encountered in new territories. In early America, however, colonists also appropriated Native culture in order to distance themselves from the places they had left behind. “Indianness,” Deloria and other historians have argued, helped colonists define themselves as separate from their Anglo-Saxon roots and allowed them to fantasize about a connection to the continent’s history. In the eighteenth century, American colonists didn’t think that they needed the British anymore; they chafed at British attempts to control trade and to keep them near the coast for the sake of collecting taxes. “Indian” costume was adopted by militias and other groups of white men throughout the colonies to protest land-use laws and intimidate British officials. Native imagery appeared in colonial newspaper mastheads, military flags, and patriotic songs. In 1772, colonists pretended to be Native Americans and set a British ship called Gaspee on fire. In 1773, most famously, white men dressed up as Mohawks for the Boston Tea Party.

After the Revolutionary War, America’s relationship to Indianness changed. The “Indian problem,” as it was popularly called, was seen as an obstacle to western expansion, and enthusiastic performances of Indianness became a kind of neurotic response to the mass extermination of Native people. “Ironically, as the assault on Native religions and lifeways continued,” Angela R. Riley and Kristen A. Carpenter wrote in the Texas Law Review, “Americans increasingly fetishized the Indian.” Indian-inspired men’s clubs and societies proliferated in the mid-nineteenth century. In cities, fraternities gathered in dark halls to initiate white people into the mysteries of “Indianness,” and in rural areas they gathered around fires deep in the woods. The Tammany Society burned an effigy of “The Old Chief”—a make-believe “Indian saint”—in a fake wigwam to celebrate American abundance. The Improved Order of Red Men met throughout New England for monthly campfires where they dressed like Natives and called one another by what they believed were Native names. Out of the order grew an auxiliary group for women called the Degree of Pocahontas. The Boy Scouts of America grew out of a youth group called the Woodcraft Indians, which promoted “Indianness” as a way to teach Americanness to white boys. (Until last year, Boy Scouts were still allowed to dress up as Indians at official events.)

In the early nineteenth century, Americans wrote and staged dozens of so-called Indian dramas that romanticized the precipitous decline of the Native population. These performances popularized the tradition of the “stage Indian,” a term for the portrayal of Native Americans by white actors. The 1829 play Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags—which tells the story of the tragic defeat of an Indian chief during King Philip’s War in seventeenth-century New England—was the most popular Indian drama of the time. Edwin Forrest, the white man who played Metamora, was the era’s most famous stage Indian. Metamora opened the year before Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, ordering tribes to migrate to territory west of the Mississippi River and causing the deaths of thousands along the Trail of Tears. Historians have argued that Indian dramas were a device for white Americans to work out anxieties about the genocide of Native Americans. “There was,” Deloria writes, “quite simply, no way to conceive an American identity without Indians. At the same time, there was no way to make a complete identity while they remained.”

In both Indian dramas and minstrel shows, which were popular around the same time, the use of redface and blackface were often justified as necessary stage devices, required to make the show more realistic. Yet at the same time, plays needed to reassure audiences that underneath the red paint or shoe polish the performers were actually white. “The risk of playing Indian to become American was playing Indian too convincingly,” Jill Lepore writes in The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity. “If spectators were seduced by the tragedian’s seamless acting into believing that he really was an Indian then they were applauding a ‘bloody barbarian.’ ”

Left: Andrew Wasserburger (center) and Ben Hanson (right) at the Spirits Liquor Lounge. Right: A performer watches others apply iron-ore face paint.

In The Legend of Rawhide, there are lots of Indians: maybe forty or fifty white people in redface. About twenty of them play the role of “Brave.” Offstage and out of costume, they travel around in a pack, wearing ranch gear, muscle tanks, and iridescent Oakleys. One has a big tattoo of an “Indian chief” on his arm. I meet most of them by the horse trailers. When I arrive the animals whinny and stamp in the heat. Among the men playing Braves, there’s Cody, Cuinton, and Colt, who wears a shirt that’s torn and bloodstained at the elbow from a cattle-branding accident. J.V. Bolden is a blue-eyed, long-lashed white man in his thirties who plays the Indian Smoke Signaler. He wears a buckskin shirt decorated with animal bones. Another cowboy playing Indian, Shawn Thompson, is a redhead who works on his dad’s cattle ranch. “Only time the hordes come down to Lusk is for this event,” he says.

“Why do you do this?” I ask.

“Adrenaline rush,” Shawn says.

They had all either grown up ranching in Lusk or had come here to find work. Some ride every day in the spring, summer, and fall, and when the day ends they take the saddles off their horses to practice riding bareback. Rawhide is often on their minds, and most have been in the show since they were kids. This year, there’s a woman playing a Brave. “Might as well,” she tells me.

O.W. is a high school student; it’s his first year playing an Indian. “Some people say it’s fun,” he says. “Others say it’s the worst feeling of their life.” He’s with Bryce Sturman, a college student and steer wrestler with the wet eyes of a kitten. Bryce’s nephew, an infant, will also be in the show. “If you see a baby,” Bryce says, “in fifteen years that baby will be an Indian Brave.” About five years ago, Bryce went unconscious on set. “You fell right on your noggin,” another cowboy recounts, “and we were like, Holy shit, that’s what a dead guy looks like.” Bryce turns and spits. The men rein up to ride bareback. One of the bigger boys tries to mount but gets stuck with one leg over a pinto’s rear.

Closer to the arena I find Weldon, the man who plays Clyde, drinking beer with Rex Beuler, who plays the frontiersman Kit Carson. Weldon wears a lacy purple garter on his arm because the high school girls are selling them for a fund-raiser. “Five bucks,” he says. “Why not. I buy one every year.”

“What’s the best part about playing Clyde?”

“I’m the only one who gets to shoot an Indian,” he says.

Some look nervous when I tell them I’m a writer. Others ask whether I’m on the good side or the bad side, and I say the good side, even though I know we mean the opposite. In 2017, Wyoming Public Media ran a story on Rawhide with the headline legend of rawhide reenactment raises questions over native american stereotypes, and the residents of Lusk were not pleased. “They’ll shut us down one day,” says Dan Hanson, who played the Indian Chief for sixteen years but now plays the Drunk. This year, his son Dan Henry plays the Indian Chief and his son Ben plays a Brave. “They’ll do it because they want to make a splash in the news and be a big shot. Some people try to make it a racial thing, but people are pretending to be someone else in Hollywood all the time.”

The man who plays Old George the Indian Scout, Joe McDaniel, says Rawhide is about having a good time. “They are just actors. Do they get mad at people on TV for dressing up like a transvestite? As far as I know, they don’t,” he says. “It’s actually depicting the white people as the bad people. They’re the ones who started the conflict. So if we’re being racist, I guess we’re being racist against the pioneers.”

“They are good,” J.V., the Indian Smoke Signaler, says about the Braves. “They bring justice. The white guys pick the fight and the Indians finish it.”

But they seem to misunderstand the real critiques: that white people shouldn’t take on someone else’s narrative without asking, and that they shouldn’t benefit in any way from the injuries done to another group.

“Indian death is never private,” writes David Treuer in his book Native American Fiction, “it is always attended by larger meanings.” In Rawhide, the death of the Indian serves to stage the killing of the white man, which gives the settlers (and thereby the white audience) an opportunity to perform a false penance. The death of the white man conjures images of Christ’s resurrection and absolution for white sins. The white man’s death is staged to make the Indians look like barbarians. But in fact, the Lakota never skinned people alive. “Yes, it is all too safe to practice on us,” Treuer writes, “to express oneself through us and our predicament. It is not necessary (and this is the root of our appeal) to be informed, actually informed, about our realities.”

“It’s cool to us more than anything,” says Brian Clark, the Medicine Man. “This is one of the best adrenaline rushes I’ve ever experienced. I’ve seen fans climb over people to get away from us.”

“And with the utmost respect,” his friend says, holding two cans of Keystone Light. “Literally. I mean, we know we aren’t Indians.”

The Rawhide script was written by a college student in 1946 at the request of the town doctor, Walter Reckling, who wanted to give World War II veterans a special homecoming. It was performed pageant-style, outdoors, in the fairgrounds. Back then, all the costumes were made from materials and with tools that would have been available in 1849. The men playing Indian wore loincloths and rode bareback either without reins or with their reins in their teeth so they could still string a bow. Before the premiere, Reckling made a papier mâché body cast of the actor playing Clyde, and painted it red. He fitted it with flesh-colored long johns that Braves would then peel off as if skinning him.

The script hasn’t changed much since 1946, except for an edit changing “savages” to “hostiles” and removing the word “squaw.” The play doesn’t grapple with any real conception of Native Americans or any consideration of their plight in the new nation. Rather, it relies on images of the “noble savage” and stereotypes from popular culture. The Indians are not given any interiority or dialogue. They speak in grunts and hand gestures. They say “how” for hello, in what Barbra A. Meek, a professor of anthropology and linguistics at the University of Michigan, has termed “Hollywood Injun English.” An omniscient narrator describes the Sioux as “godless and primitive people with their different skin” and calls them “redskins.” The narrator also talks about an Indian “who bet his own scalp and lost,” adding that later the scalp “was won back and restored to its original owner,” as if he were a mythological creature who might survive this process unharmed. The Indian Princess, who is not given a name, appears in a single scene, the scene of her murder. She walks onstage only to die.

The participants I met were not mean-spirited, but they were uncritically handing down racist narratives. When I spoke with Rebecca Tsosie, a Regents Professor of Law at the University of Arizona, she reminded me that Native people have to deal with America’s frontier mentality everyday. “We see it in the Sauvage perfume advertisement, at fashion shows, sporting events, Halloween—Americans are playing out this mythology and it’s seen as an American thing to do. They say they are celebrating the past, but the past is still present for many Native Americans. These are images that are replete with physical and cultural genocide, and there is no good way to celebrate genocide.” She mentioned a case that took place not far from Lusk, in South Dakota, where Lakota schoolchildren attended a sporting event where they were sprayed with beer and called disparaging names. More recently, at a high school volleyball game in Arizona, members of the audience chanted racial slurs and referred to Native players as “savages.” “It’s important that the history of Native Americans and the contemporary experience are not delinked,” she said.

Redface, like blackface, is a sin of white supremacy: it assumes other cultures are there for the taking. To wear face paint and a headdress, smoke from a “peace pipe,” perform the so-called “tomahawk chop” of the Atlanta Braves, or speak broken English—these are examples of racist appropriation. But many Americans don’t want to recognize it.

Dan Henry Hanson, as the Indian Chief, and Brian Clark, as the Medicine Man, during a performance.

On Friday, there’s a station set up behind the tepees where the performers put on redface. It’s a disturbing scene. The station is stocked with supplies the organizers think will help white people look like Native Americans: buckets of iron-ore paint, brushes, towels, a plastic bin that holds what cast members call “Indian wigs.” The ground is covered with red puddles. A girl smooths the paint onto a boy’s back. “So gross,” she says. “This shit is so fucking gross.”

The cowboys also paint the horses—circles around the eyes, a lightning bolt on the rear. They swap their boots for moccasins, tank tops for rawhide tunics and vests, and Wrangler jeans for dirty khaki pants. They brush their hair into Mohawks or slip on ratty black wigs with loose braids. One boy wears a leather top hat from a garage sale, and another ties a rag across his forehead, Rambo-style. They fuss with their wigs. “Does it look ridiculous?” one asks. “Should I get another?”

They practice being Indian. They bellow imitation war cries and ride horses bareback in loops around the arena. In the daylight, the dark paint makes blue eyes shine brighter. Blond hair pokes out from under crooked wigs and patches of skin still need covering. They are all galloping by, their horses’ hooves tossing dirt. A group of them surrounds a man taking photos; he calls them wild, and they take it as a compliment.

The man who plays the Medicine Man, Brian, sips from a can of Arnold Palmer, and his friend, a Brave, drinks Keystone Light. The Medicine Man wears big buffalo horns on his head. “They are old,” he says. “I don’t know where they came from originally, but they’re real. Heavy and hot.” He points to the arena. “Someday my kids are going to be there and maybe my son will have these horns one day.”

The Indian Chief, Dan Henry, is off by himself, over by the arena. He stands with his legs apart and his arms crossed. He says being the chief is a big responsibility and he’d rather just play a Brave. He wears high-top moccasins, a fringed rawhide shirt, and khaki pants stained with fake blood. “It’s a little greasy,” Dan Henry says, touching the paint on his skin. “It’s really hard to wash off, but the Natives used it as sunblock and I thought that was really cool.” He also wears a faux eagle-feather headdress, an imitation of a sacred item worn by Lakota warriors such as Chief Sitting Bull and Chief Red Cloud. Each feather represents an honor. (Under federal law, only Native Americans are allowed to handle or possess headdresses with real eagle feathers.) “We used to have one that came from the Sioux,” he says. “It had real eagle feathers. I ordered this one online.” There’s a headdress at the Stagecoach Museum in town, in the small area on the second floor devoted to Native Americans. The plaque in front of the plexiglass display doesn’t say anything about the importance of the headdress to the Native Americans, only that it was a “Headdress worn by Chief Sitting Bull given to Honorary Lakota Chief George Earl Peet by Sitting Bull’s daughter, Standing Holy, sometime in the 1920s.” Nearby is a photo of Peet, a white man, wearing the headdress as Indian Chief in the 1955 production of Rawhide.

An hour before Friday’s show, a thunderstorm brings rain to the arena. Everyone ducks for shelter, and I follow the cowboys to the trailers. Girlfriends and wives frantically spray flaccid Mohawks, touch up face paint, and adjust wigs. I find Cuinton with his feet dangling off the back of a horse trailer. He’s a blond, blue-eyed teenager with freckles, and today he’s wearing a fringed suede vest and a black wig with two long braids. He looks like he’s dressed for the wrong show—more like a kid trying to be a hippie than an Indian. He’s from Oklahoma, and he’s been managing ranches since he was fourteen. He talks for a while about the Dust Bowl and then asks if I’m from PETA. I say I’m not, and he says he’s had it with them. We stare out at the rain. “I got a bright-red Make America Great Again sweatshirt I should totally put on when I ride,” he says. “This is the only thing Lusk does all year, and it’s fucking fun as hell. It’s where we all get to cut loose even when we are on probation.” He takes a big, gurgling sip of his drink. “Last year was my first year riding in it. If you’re our age and you’re not an Indian Brave, you’re a pussy.”

The Skinning Tree

To the west of Lusk is the Wind River Reservation, home to Wyoming’s Shoshone and Arapaho tribes, and to the northeast, across the border in South Dakota, is the Pine Ridge Reservation, home to the Oglala Sioux. While on my trip out West, I visited the Pine Ridge Reservation and the site of the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee, where U.S. troops opened fire on a gathering of Lakota, killing as many as three hundred men, women, and children. The memorial was hardly visible—it would have been easy to drive by and miss it. It was not busy with tourists, like the nearby Mount Rushmore. A small graveyard sits atop a hill, and across the road there is a small turnaround next to a historical marker. In the grass nearby, Native women were selling handmade souvenirs on folding tables. The first woman I approached was in her twenties. I told her about Rawhide and showed her photographs of the performance. “No, we don’t know about this,” she said. “It’s extremely offensive.” When I described the plot of the play, she shook her head. “That’s a bad story,” she said.

At the next table I met Valerie Brown Eyes and Germaine Red Cloud, a descendant of Chief Red Cloud. A relative of hers had survived the massacre. She works at this table every day making jewelry.

Again, I asked about Rawhide. “No,” Brown Eyes said. “No one told us about this. No one asked our permission. There are laws about this. You know, I used to get really mad when white people pretended to be black.”

“I’m sorry you had to see that,” a man sitting nearby told me. “We know how they are in Lusk and we try not to stop anywhere near there. We keep on moving through.”

“You know,” Germaine said, “the true meaning of ‘Indian’ is godless, savage heathen. That’s how they viewed us—godless, savage heathens. Because we didn’t look like them or talk like them. That’s why they have done what they have done to our ancestors. They killed us like we were nothing. But we are healing all the time, we are healing when we get to share our stories.”

Weldon Tschacher in the role of Clyde

The final performance of Rawhide is Saturday night. The flaps of the set’s tepees are smeared red from all the people entering and exiting. The Pioneer Women lift up their long prairie dresses to step over deep red puddles while Braves paint themselves. O.W. is trying to spread iron-ore paint over his back. “Did I get my butt crack?” another says. A teenager standing to the side jeers at the cowboys, “Hey, this is blackface—this is racist!” I stop him to ask about his comment, wondering if he’s serious. He backs away sheepishly. “Just kidding,” he says.

At twilight, hundreds of people fill the stadium seats. The light is soft and purple, and the insects sing. There are two ambulances parked by the bleachers because every year someone gets hurt. Actors fall off their horses, get trampled by hooves, crack a skull or break a bone. One year a man caught on fire. So far, no one has died.

After I sit down, I overhear a girl say to her friend, “Let’s sit up high in the stands. I’m scared of the Indians.” The performance starts out like a football game. Most of the performers gather on either side of the stage. The Braves and residents of the Indian Village stand by the tepees while the white settlers stand by a fake waterfall. A voice over the loudspeaker asks everyone to observe a moment of silence for veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Then a song by Toby Keith called “American Soldier” plays while women march by carrying flags and ride by on horses. Then it’s time for the national anthem. The crowd stands at solemn attention. Onstage, all the white people dressed like Indians put their hands on their hearts.

After the anthem ends, the actors disperse and find their places. There’s no more chatter of politics, no talk of the news of the world—only the bright stadium lights, the costumes, and the anticipation of the night’s return to that time in America’s past from which the fantasies on display originate. “So come with me,” the narrator says, “back to those long gone days some eight score and ten years ago. Come with me . . . into your imagination. See the West as it was.”

The play begins with residents of the Indian Village hunting antelope, starting fires, relaxing, betting on horse races, playing games, and throwing spears. The white settlers soon arrive, coming around the hill in covered wagons, and form a circle in the dirt onstage. There’s square dancing, gambling, and some prayers for Jesus. There are fires. A Brave steals a goat. The Drunk falls in a water hole. There are encounters with the Mountain Men, the Jesuit Priest, Kit Carson, the Cavalry, and Shady Ladies.

The Indian Princess is shot in the dark. Howling women drag her away. In the morning, a Brave confronts the wagon train and tells the Pioneers about the murdered woman. He requests that the killer give himself up, and says that if he doesn’t, they’ll go to war. Clyde is nowhere to be seen.

Braves gather on the hill behind the stage, and I can only see their silhouettes, backlit by real fires that have been set in the distance. They follow the Chief down the hill, and when they reach the stage they bring the horses to a sprint. They run circles around the wagons while the Pioneers take them out with blank guns. The air fills with the smell of gasoline and smoke. In an unscripted moment, a Brave falls off his horse and hits the ground. His girlfriend runs across the stage, screaming. An Indian wig is on the ground beside him. The emergency workers run to his side; give him oxygen; strap a brace to his neck; lift him onto a stretcher and into the ambulance, and speed away.

The show goes on. Clyde surrenders and the stage goes dark but for an orangish glow that illuminates the Skinning Tree. The Braves remove his shirt and tie him to the trunk. The Chief starts skinning Clyde while the performers make strange animal sounds and pump their fists. When they finish, Clyde is alone, stuck there on the Skinning Tree, dripping with blood, the purple garter still tight around his arm. Under the white stadium lights, he looks delicate, like a teenage Christ martyred in a school play. When the show ends, the Braves raid the bleachers and the crowd screams. “To make it more realistic,” one of the organizers explains.