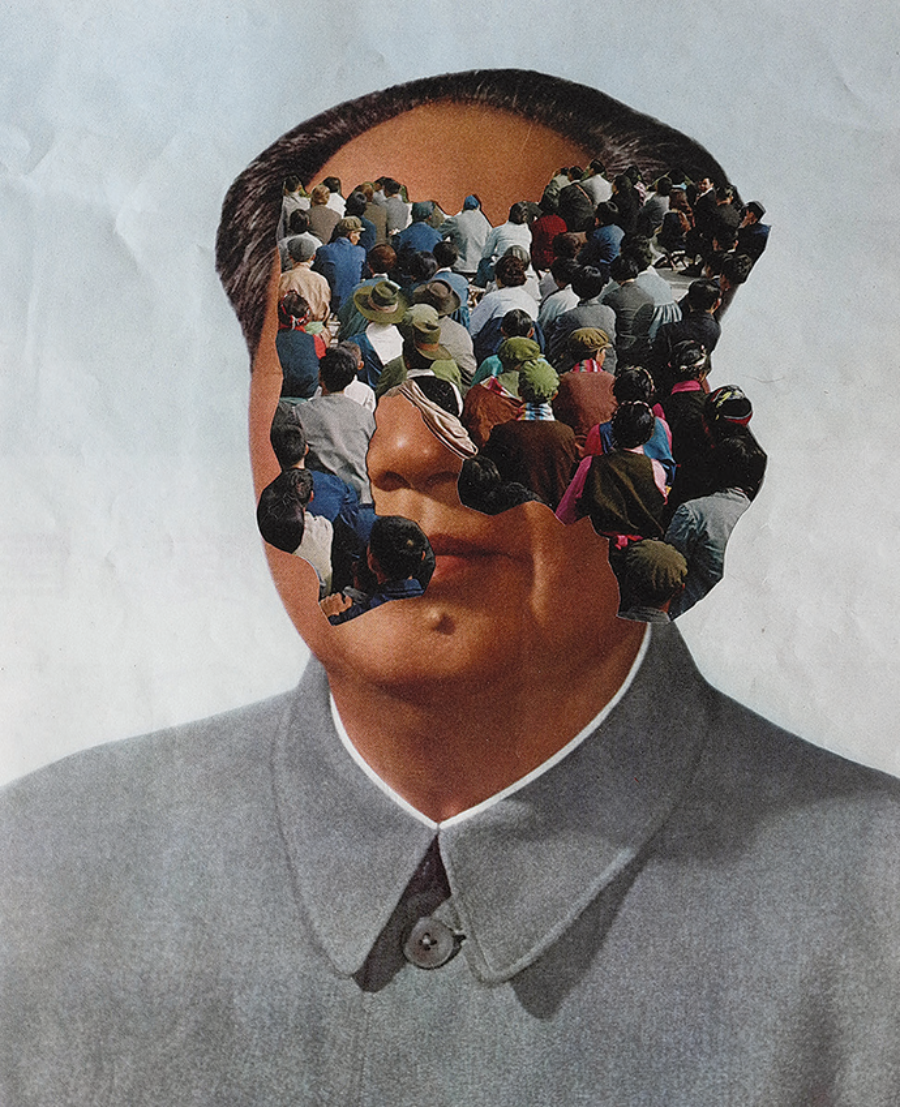

China X, by Caio Reisewitz © The artist. Courtesy Luciana Brito Galeria, São Paulo

Discussed in this essay:

Maoism: A Global History, by Julia Lovell. Knopf. 624 pages. $37.50.

In 1973, the year after Richard Nixon’s historic visit to the People’s Republic of China, Shirley MacLaine made her own trip to the country, which she recorded in her memoir You Can Get There from Here.

In China, we saw low food prices, and streets free of crime and dope peddling. Mao Tse-tung was a leader who seemed genuinely loved, people had great hopes for the future, women had little need or even desire for such superficial things as frilly clothes and make-up, children loved work . . . Relationships seemed free of jealousy and infidelity because monogamy was the law of the land and hardly anyone strayed . . . I had a growing feeling that the Chinese way might be the way of the future.

As Julia Lovell—a professor at Birkbeck, University of London—writes in her new book, Maoism: A Global History, a year after returning from China, MacLaine concluded, on further reflection, that Mao’s maxim, “serve the people,” was also an instruction to serve herself. She then opened a solo cabaret show, “announcing (while draped in zircon-studded peach chiffon) to perplexed reporters on the first night that ‘Mao Zedong is probably responsible for my being here.’ ”

MacLaine’s endorsement, though it may well have been the kitschiest, was hardly uncommon. Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, Maoism was embraced by intellectuals in Paris, Rome, Berkeley, and New York as a fresh “Third World” vision of equality; by revolutionaries in India, Indonesia, and Peru as a guide to guerrilla war that could transform society; and by dictators in Cambodia, Zimbabwe, and Albania who enjoyed the ample Chinese cash that came with their pledges of fealty to its leader. These legacies, and many others, began with the colossal ambitions of Mao Zedong himself.

Mao was a revolutionary, a murderer, a philosopher, an insomniac, a Svengali, a poet—and, according to the Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, “the baddest motherfucker on planet earth.” More than four decades after his death, in 1976, Mao is still an international celebrity; one of Andy Warhol’s silk screens of Mao’s face recently sold for $12.6 million. While he ruled China, his power was stunning. Mao’s word could transform a minister into an outcast or an ordinary worker into a revolutionary hero. His policies restructured China and led to some of the greatest disasters of the twentieth century, including a man-made famine that killed more than thirty million people.

Mao bequeathed to the world ten known children, countless poems and calligraphy, and numerous pithy sayings seemingly made for Twitter (“A revolution is not a dinner party”). But Mao also produced a voluminous body of writings that described his vision for China’s revolution and Chinese Marxism—a set of ideas and practices referred to as Maoism. Beyond China, Lovell writes,

and especially in the West, the global spread and importance of Mao and his ideas in the contemporary history of radicalism are only dimly sensed . . . They have been effaced by the end of the Cold War, the apparent global victory of neo-liberal capitalism, and the resurgence of religious extremism.

Yet to Lovell, understanding Maoism not only “unlocks the contemporary history of China,” but also allows insight into “global insurgency, insubordination and intolerance across the last eighty years.” Lovell’s ambitious and sweeping history of Maoism undertakes, in her own words, “to bring Mao and his ideas out of the shadows, and recast Maoism as one of the major stories of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.”

What is Maoism? For Lovell, as for many scholars before her, this question cannot be answered in simple terms. Maoism developed over the many decades of Mao’s life as, by turns, a doctrine of violent revolution adapted from Marxist-Leninist principles; a vision of the solidarity and shared development of oppressed people around the world; a set of military tactics for insurgency; and a cult of personality. Follow the thread of Maoism even briefly and it splits into dozens of strands.

Everybody Must Get to Work to Eliminate the Sparrows, 1956, by Liu Jiyou.

Mao derived most of his political theories from a process of analyzing and embracing what he lovingly called “contradictions,” that is, the oppositional forces within everything from plants to societies that propel their development. It is perhaps unsurprising that, as Lovell writes, “Maoism” as a term has been used “both admiringly and pejoratively,” with meanings “ranging from anarchic mass democracy to Machiavellian brutality against political enemies.” In English, she continues,

“Maoist” and “Maoism” gained currency in U.S. Cold War analyses of China, intended to categorize and stereotype a “Red China” that was the essence of alien threat. After Mao’s death, they became catch-all words for dismissing what was perceived as the unitary repressive madness of China from 1949 to 1976.

Lovell herself uses Maoism as “an umbrella word for the wide range of theory and practice attributed to Mao and his influence.” In other words,

The term is useful only if we accept that the ideas and experiences it describes are living and changing, have been translated and mistranslated, both during and after Mao’s lifetime, and on their journeys within and without China.

These characteristics of Maoism—as protean, contested, and portable—partly explain its extraordinary resonance: people could take from it selectively and eclectically. But, early on, Mao also developed several important and enduring ideas.

Marxism in its origins primarily focused on the industrial proletariat, but Mao’s model, unlike the one that guided Lenin and the Russian revolutionaries to victory, suggested that the peasantry could become the revolutionary social class. Born to farmers in Hunan province, Mao knew rural China well. The young Mao became an urban intellectual, working as a librarian at Peking University and spending time with Marxists and anarchists. Active in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from its founding in 1921, he began to consider the countryside anew. When Mao surveyed China, he found a land mired in rural poverty and near-feudal inequality, worsened by the oppression of foreign imperialists. The Chinese Communist Party would succeed by lifting up the peasants and “surrounding the cities from the countryside.”

This dictum was also Mao’s military strategy for winning the civil war that broke out between the CCP and the ruling Nationalist Party (the Kuomintang, or KMT) in 1927. Then, when Japan invaded China in 1937, Mao partnered with the KMT to defend the nation. This war against Japan’s expanding empire further seared a powerful commitment to anti-imperialism into the story of the Chinese Revolution.

As violence raged, Mao let the KMT do the bulk of the fighting while he focused on disciplining the CCP. In a series of “rectification” campaigns, Mao and his lieutenants developed techniques of “thought control” and repression to indoctrinate cadres and punish the disloyal; American writers would use the term “brainwashing” to describe it. (And as the Uighurs in Xinjiang are experiencing today, this aspiration lives on, horrifically, among China’s current rulers.) It was no coincidence that soon after these campaigns the CCP wrote “Mao Zedong Thought,” defined as the “sinicizing of Marxism,” into the party constitution.

Maoism became a governing ideology as the CCP declared the founding of the “New China” in 1949. The immense task of rebuilding the devastated country called for ideas that could inspire the people and give them a sense of direction. Yet it continued to evolve erratically in the decades that followed, in tune with Mao’s careening priorities—at one moment, he would demand that people work around the clock to surpass Britain in steel production, and at the next he called for all the sparrows in China to be killed in a campaign against “pests.” No matter how the official line shifted, Mao was right: Lin Biao, for a time Mao’s designated successor, explained, “The thoughts of Chairman Mao are always correct. He is never out of touch with reality.”

Maoism reached its frenzied peak of influence during the Cultural Revolution, when Mao’s sayings—collected in the Little Red Book—became pervasive in everyday life. Mao stood as a divinity to the millions of youthful Red Guards who were his foot soldiers in this rebellious, anarchic movement to “bombard the headquarters” and remake Chinese society and culture. They quoted his words as they assaulted senior political leaders, teachers, and people deemed to have bad class backgrounds: “To rebel is justified.”

The brutality perpetrated in the name of the Little Red Book was stunning. Between 1966 and 1969, according to the scholar Andrew Walder’s Agents of Disorder: Inside China’s Cultural Revolution, nearly 1.6 million people died in mob violence, factional warring, and sheer chaos. The decade of tumult ended officially only after Mao’s death, on September 9, 1976. Following the announcement, state-mandated public histrionics began immediately, though the historian Frank Dikötter found evidence of significantly less mournful private reactions. Overnight, the southern city of Kunming sold out of liquor.

Spring and Autumn—1949 50 Chinese Note (Workers and Peasants), embroidery on silk by Shao Yinong and Mu Chen © The artists. Courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong, and Yavuz Gallery, Singapore

Mao and Maoism, with all its nihilism and violence, found a surprising degree of international support. From the early years of Mao’s time as the leader of the CCP, Lovell shows that he focused on international propaganda—including many hours spent with the American writer Edgar Snow, who wrote the hagiographic 1937 bestseller Red Star over China, presenting Mao to the world as China’s humble savior.

Mao was not content with dominion over all of China; he craved recognition as a great leader of the worldwide Communist movement. Although the building of the New China owed a great debt to Soviet assistance, Mao soon grew impatient with this overbearing “elder brother.” After Joseph Stalin’s death, Nikita Khrushchev delivered a speech in 1956 denouncing Stalin’s cult of personality, just as Mao was building his own. Relations between the two countries deteriorated, and Chinese leaders bragged to Moscow in 1960: “The center of world revolution has shifted to China, and Mao Zedong is the greatest contemporary Marxist.”

Some left-wing thinkers in the West agreed. Mao’s writings became touchstones for disaffected youth and oppressed minorities from Berlin to Oakland. He earned the respect of many feminist leaders with pronouncements such as “women can hold up half the sky” and meaningful improvements to women’s opportunities (though the Party’s culture itself remained highly patriarchal, and as Lovell notes, Mao was notably priapic; he may have “knowingly infected his paramours with venereal disease”). The CCP also deliberately cultivated American civil-rights activists, feting W.E.B. Du Bois in Beijing in 1959.

For those who decided that armed struggle rather than peaceful protest was the way forward after the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., Mao and the Cultural Revolution offered a road map for ferociously remaking society. For others, Maoism seemed to be as much aesthetic as political. The French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard, who made the influential 1967 film La Chinoise, about Maoist college students in France, exclaimed rapturously, “What distinguishes the Chinese Revolution and is also emblematic of the Cultural Revolution is youth.” In the early 1970s, Andy Warhol told a friend, “I was just reading in Life magazine that the most famous person in the world today is Chairman Mao.” Soon thereafter, Warhol added Mao to his roster of ubiquitous subjects, alongside Marilyn Monroe and the Campbell’s soup can. Awareness of the horrors of China under Mao came slowly, and many of these acolytes were shocked when they learned how much trauma the regime had inflicted on its people.

Untitled (Chairman Mao and Sparrows), by William Kentridge © The artist. Courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

But Mao sought much more than fame and approbation. He wanted to change the world, leading the Global South in waging “people’s war” against what he derided as the “paper tiger” of imperialism. To realize Mao’s grandiose ambitions of sparking world revolution, the CCP engaged in a remarkable effort to support favorable regimes and train rebels who pledged allegiance to Maoism.

Mao gave generous financial support to sympathetic governments, no matter how thin China’s wallet grew. Lovell reports that China’s international aid totaled more than $24 billion between 1950 and 1978, a period during which China had a per capita gross domestic product well under $200—less than 2 percent of that of the United States at the time. Even as famine ravaged the Chinese countryside, Algeria pocketed 50.6 million yuan in 1960 (compared with only 600,000 yuan the year before), and Albania received vast shipments of grain that could have fed dying Chinese. In the early 1970s, China spent at least 5 percent of its national budget on foreign aid.

From southern Africa to Southeast Asia and Latin America, Mao’s China also fomented violent revolutions. The CCP specialized in supporting what Lovell calls “low-tech peasant insurgencies,” which used the strategies that had brought the CCP to power in China. Often these interventions led to disaster. In Indonesia, for example, Chinese leaders encouraged and trained the Communist leader D. N. Aidit alongside other guerrillas from across Southeast Asia. Aidit was killed after a failed coup in 1965, which was followed by murderous purges, led by the Indonesian army, that killed at least five hundred thousand suspected Communists and ethnic Chinese.

In the mid-1960s, Maoist China also trained the Peruvian Abimael Guzmán, who returned home to establish the militant Shining Path group, which grew slowly before attempting an uprising against the Peruvian government. Guzmán’s brutal tactics in Peru’s long conflict took direct inspiration from Mao. Similarly, the Indian Maoist rebel Charu Mazumdar received training and support from the CCP before launching an uprising in West Bengal in 1967 that grew into the enduring Maoist Naxalite insurgency, which continues to carry out high-profile attacks in India today.

Perhaps the most gruesome case is the Khmer Rouge regime, which was led by the avowed Mao disciple Pol Pot. On a visit to China, Pol Pot met with Mao poolside. “Since I was young, I have studied many of Chairman Mao’s works, in particular those concerning people’s war,” Pol Pot declared. “The works of Chairman Mao have led our entire party.” The result was stunningly murderous. The Khmer Rouge’s genocidal policies led to the deaths of approximately 1.8 million people between 1975 and 1979, more than one fifth of Cambodia’s population at the time. “Without China’s assistance,” the scholar Andrew Mertha concluded, “the Khmer Rouge regime would not have lasted a week.”

Of course, China was far from the only twentieth-century power to foment revolutions or seek to influence other countries’ domestic politics: both the Soviet Union and the United States far surpassed Mao’s efforts. But too often the Cold War is recalled as a story shaped only by the decisions of those two towering superpowers. Lovell’s book, building on work by historians such as Odd Arne Westad, Shen Zhihua, and Chen Jian, reminds readers that China was also a central player in shaping the conflict. China today claims to have a long history of nonintervention in other countries’ affairs, but historical evidence to the contrary is overwhelming.

Despite the violence it inspired, Maoism was embraced around the world not simply because of cash, guns, and propaganda; it offered empowerment to people fighting against empire, capitalist exploitation, or state-backed injustice. Mao’s China, Lovell writes, “provided an example of a poor, agrarian country persecuted by Western or Japanese expansionism standing up for itself.” Mixing socialist ideals with nationalist rebellion, Mao’s message resonated intellectually and emotionally. Its welcome was an indicator of how profoundly unjust many understood the world to be.

Yet Lovell ultimately concludes that Maoism failed to help many of the people it promised to benefit. From Cambodia’s killing fields to the Peruvian highlands, it helped to motivate and justify the persecution of vulnerable populations. As another example, Lovell cites Zimbabwe, where in the 1980s the dictator Robert Mugabe told Chinese premier Zhao Ziyang, “No country [has] helped [our movement] more.”

Maoism’s praise of violence and rebellion made it inherently unstable when its adherents came to power, Lovell argues, and its commitment to party and thought control was conducive to brutal authoritarians. But do these attributes of Maoism really explain Zimbabwe’s woes? After all, the United Kingdom, United States, Soviet Union, and even Cuba and North Korea played roles in the struggle that led to the creation of Zimbabwe. Lovell emphasizes Maoism wherever she finds it, but sometimes the label feels like ?it barely sticks.

Name-checking Donald Trump and Nigel Farage, for example, she claims that Maoism is “vital” to understanding what she calls the radicalism that has arisen across the world in response to material and political desperation. “Over the last two years,” she writes,

the election of Donald Trump and the rise of European populist politics have brought questions of sovereignty under new scrutiny. In the UK, for example, does it reside with “the people” (as a demagogue like Nigel Farage argues), or with Parliament? What is the relationship between the “will of the people” and the specialist elite who legislate in the capital? These are questions with which Maoism has grappled—often with violent results. . .

But Farage’s xenophobia and nativism seem at least as important as his populism. And the notion that desperation engenders “radicalism” was hardly invented by Mao—Trump certainly seems to have figured it out without bringing the chairman into the matter. It would be more accurate simply to say that though Maoism may not significantly help us understand Trumpism, Trump nevertheless has more than a few Maoish qualities. And in a world of worsening inequality, in which a majority of the poor live in rural areas, Lovell could have done more to acknowledge that particular aspects of Maoism’s radical message still resonate today.

Lovell’s critique of Maoism as conducive to the building of violent, repressive regimes is most persuasive when applied in a more limited fashion to Chinese politics. Mao bequeathed to the CCP a form of strongman authoritarianism that was built on the contradictory forces of struggle, upheaval, and obedience to an all-powerful leader. He has remained a core part of the narrative that justifies the CCP’s rule; Deng Xiaoping said in 1980, “We will not do to Chairman Mao what Khrushchev did to Stalin.” Xi Jinping took advantage of that legacy, becoming what Lovell calls the “most Maoist leader the country has had since Mao.” Xi strengthened Mao’s historical prestige, pushed for global power, and deployed many of Mao’s strategies of party governance and propaganda, including eliminating term limits and strengthening a twenty-first-century personality cult. On the 120th anniversary of Mao’s birth, Xi bowed three times in front of a statue of the man, paying homage. The People’s Republic that Mao founded still stands today.

But even within China’s borders, Mao’s legacy is more complex. Mao is also deployed by Chinese critics of the regime. Critics on the “right”—primarily classical liberals who call for freer markets and more open politics—argue that China’s rulers will never modernize unless they sanction a fuller and much more negative historical evaluation of Mao, including the horrors of the Cultural Revolution. Critics on the “left”—who are committed to more orthodox Marxist or Maoist ideas, as the analyst Jude Blanchette argues in his recent book, China’s New Red Guards: The Return of Radicalism and the Rebirth of Mao Zedong—contend that the feverish pursuit of economic growth over the past forty years has fundamentally broken the egalitarian promises of the Chinese Communist Revolution. For both sides, Maoism is a central issue shaping contemporary China, albeit in ways that are profoundly different from what Mao himself expected.

In the end, Maoism achieved few of its intended goals—whether eliminating rural poverty or placing China at the center of a worldwide network of communist states—and a host of unintended consequences: famine, failed revolutions, and the embrace of capitalism following Mao’s death. Outside of China, the only Maoist party in power in recent years was in neighboring Nepal, which waged a “people’s war” before embracing electoral democracy and ultimately merging into the ruling Nepal Communist Party. Perhaps the most delightful moment of this book so filled with tragedy comes when Lovell recounts an interview with one American former acolyte of Mao who had left the cause years before. He told Lovell that “Maoist techniques” remained highly useful to him: “I moved into a condo a year ago. I’m already on the organizing committee. I can analyze contradictions straight away. That’s what Maoism has done for me.”

Recapturing both the allure and the aggression of global Maoism illuminates the power shifts under way today, as the Chinese leadership under Xi Jinping is seeking anew to win recognition of its centrality to global affairs. Xi, born in 1953, grew up hearing constant claims that “the center of world revolution has shifted to China,” and these ideas seem to have powerfully influenced his outlook. He believes that China’s experience “offers Chinese wisdom and a Chinese approach to solving the problems of mankind” and revels in leaders of developing countries once again traveling to Beijing to learn and seek aid. This time, however, the delegations are governments in power, many of them elected officials, rather than ragtag bands of Communist rebels.

Indeed, the history of global Maoism is most significant for its striking differences from, rather than its continuities with, the present. In Washington, it is now a common refrain that China is “exporting authoritarianism,” spreading its political practices and ideas around the world. Commentators warn of a Cold War–style standoff between the United States and China.

But in painting fearful images of China trying to build an illiberal world order headquartered in Beijing, American policymakers risk several errors. First, they ascribe a coherent ideological agenda to a regime that is struggling to develop one. Xi’s attempt at theory-making is the verbose and vague “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” which offers up Chinese nationalism, total loyalty to Xi and the CCP, and the mixed economic system that has governed China for several decades. No other country has come close to adopting it; the most prominent international appearance of Xi’s The Governance of China was on Mark Zuckerberg’s desk when the Facebook founder was unsuccessfully courting Chinese regulators to open the Great Firewall to the social-networking platform.

One should not exaggerate the appeal and success of Beijing’s efforts to catch up to the United States in soft power and international influence. Some international leaders certainly are drawn to no-questions-asked Chinese aid and impressed by no-questions-allowed Chinese authoritarianism. But even in those societies—from Ethiopia to Ecuador—nationalism may push powerfully against total alignment with Beijing, just as it did against Washington and Moscow during the Cold War.

In reaching into democratic societies, the CCP’s primary focus appears to be undermining criticism of China. Influence operations and certainly electoral interference are deeply concerning and merit a strong response, but they have little in common with the ambitions of revolutionary Maoism. More fundamentally, the most significant cases of democracies sliding toward illiberalism—Hungary, Turkey, Brazil, even the United States under Trump—are not driven by CCP influence.

Lovell’s history underscores just how difficult it is to export a political idea wholesale, whether that idea is Maoism or the rule of law. Local context and the dynamics of interpretation, resistance, and adaptation shape how ideas flow, even from very powerful countries to much weaker ones. “However closely the party state has tried to mold and direct its global image,” she writes, “its initiatives forever spin off in unexpected, uncontrollable directions.” If we are on the verge of a new period of heightened competition between the United States and China, that world will be messy, uncertain, and driven as much by events far from Washington or Beijing as by the decisions made in those two capitals.