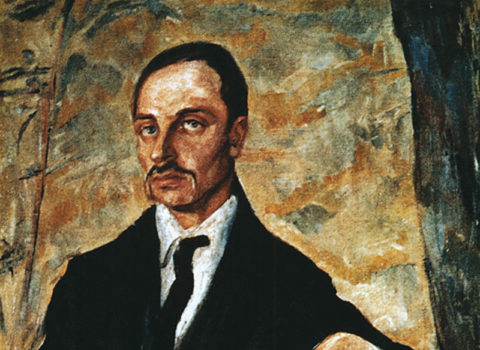

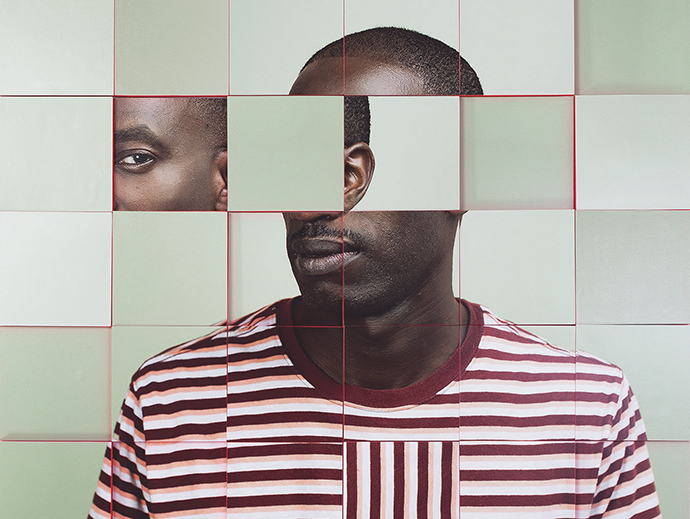

Fragment (detail), by Karen Navarro, whose work is on view this month in the exhibition Slowed and Throwed, at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston © The artist. Courtesy Foto Relevance, Houston

“Do you know why I always beat you, Daddy?” a Californian eighth grader named Sarah asks her father over chess. “Because you hate to lose pieces. . . . You can’t protect everybody. You just have to get the better of it or get the position you want.” It’s an especially ominous observation in Percival Everett’s new work, Telephone (Graywolf, $16), a novel already riddled with omens. The narrator, Sarah’s father, Zach Wells, is by his own account no more adept at life than he is at chess. Zach works as a geology professor—an expert in the remains of various bird species found in a small hollow in the Grand Canyon called Naught’s Cave—and is unenthusiastically married to Sarah’s mother, Meg, a poet. His enthusiasms, in fact, are few. Gruff with colleagues and students (especially two activists who ask him, as one of the college’s few African-American faculty members, to join a protest), lecturing on autopilot, uninterested even in the women who try to seduce him, he hides in his research and seems to find true enjoyment only in Sarah’s company. They hike—Sarah always hoping to catch sight of a bear—and compare notes on everything: the most overrated rock band, she says, is the Beatles; the most overrated painter, Georgia O’Keeffe. They agree, in unison, that Infinite Jest is the most overrated novel; “Still,” Sarah adds, “I’m sorry he’s dead.” (Neither offers a suggestion for most underrated novelist, though Everett himself would be a promising candidate.)

By the time Sarah delivers her warning about strategy, it’s almost redundant. The novel’s terrain is littered with corrupt cops and other untrustworthy, violent men, and Sarah herself is experiencing seizures and neurological lapses. As her condition worsens, Zach looks for distractions, but the ones he finds are increasingly unpleasant and threatening. A jacket he buys on eBay has an unsigned note in Spanish in a pocket, pleading for help. A drink in a bar ends with him having to physically subdue two aggressive strangers; a family vacation to Paris involves an encounter with an armed white nationalist. As the most important aspects of Zach’s life start to elude his control, it gets harder for him to judge where his responsibilities to other people begin and end. That question bends the narrative, sending Zach on a quixotic mission to New Mexico, where he plots to rescue a group of kidnapped Mexican women, one of whom seems to be the author of the anonymous plea.

Telephone is concerned with systems of meaning and communication—how they can be constructed and derailed. And like any serious novel, it’s an experiment with these systems, a game that tests its own rules as it’s played. The text is pockmarked with untranslated phrases in Latin, French, and German; with descriptions of Zach’s arcane professional findings; and with series of chess moves (“Nf3 Nxe4,” Everett writes between one paragraph and the next; “Qc2 f5”). These are clues as to how to read the story, yet they’re also, more affectingly, the tools Zach is using to try to make sense of and cope with what has happened to him—and none of them is remotely adequate to the task. The novel hints that whether one’s life is a domestic tragedy or a political thriller may depend mainly on emphasis, on how you interpret the world and which parts of it you pay attention to. Early in the book, Zach digresses from his family life to the infamous surge of femicides that began in Ciudad Juárez in the 1990s:

Some said that two hundred young women had been killed or disappeared in some twenty years. Others said it is closer to seven hundred gone. People are like that about numbers. They will say it is not seven hundred, but only three, two hundred, as if one hundred would not be truly horrible, fifty, twenty-five. . . . The numbers were so very large, obscene, fescennine. Olga Perez. Hundreds of women have no name. Edith Longoria. Hundreds of women have no face. . . . It was so uncomplicated, safe, simple to talk about numbers in El Paso, a world away. Nobody misses five hundred people. Nobody misses one hundred people. In Juárez, it was one. One daughter. One friend. One face. One name. Somebody misses one person.

The reader can’t understand at this point what these missing women have to do with Zach and his child, but it’s already clear that Zach is confronting forms of pain and injustice too vast to be understood. Like the events it mentions, the passage is hard to digest. Grief and guilt are like that, too.

Point Reyes Lighthouse with Containers, by Mary Iverson © The artist. Courtesy Paradigm Gallery + Studio, Philadelphia

The Mexican writer Jazmina Barrera also organizes her book, On Lighthouses (Two Lines Press, $19.95, translated by Christina MacSweeney), according to a deliberately alienating set of references. Each chapter begins with the coordinates and physical description of a particular lighthouse.

41° 4’ 15” N 71° 51’ 25” W

Montauk Point Lighthouse. Octagonal sandstone tower, 37 meters high, painted white with a brown stripe halfway up. The beacon uses the VRB-25 optical system. Single blink every five seconds. Foghorn: two-second blast every fifteen seconds.

A slim, idiosyncratic history of these structures and their appearances in literature—from Robert Louis Stevenson, whose father and grandfather engineered them, to Virginia Woolf, to Ray Bradbury—the book allows the reader flashes of Barrera’s emotional life amid the accumulated detail. She describes her fifth-floor apartment in New York, with views of a brick wall. “I wonder what will become of me, spending so much time without direct sunlight,” she writes. “I wonder if I’ll turn into one of those blind, transparent fish that live in subterranean rivers and caves.” In a later chapter, she visits the tiny, green-tipped, bright-red nineteenth-century lighthouse that clings to the shore of the Hudson, nearly hidden under the vast George Washington Bridge.

A lighthouse is a ready-made metaphor: for risk and rescue, aspiration and comfort, isolation and community. Barrera quotes a man in Puerto Escondido who is one of Mexico’s three hundred remaining lighthouse keepers. His problems turn out to be no more or less romantic than anyone else’s: loneliness, boredom, depression, the lure of unhealthy escapes from those things. Into this endearingly practical account of the life of a keeper, Barrera slips one of the more dramatic lighthouse stories she has collected. In 1906, Mexican president Porfirio Díaz sent Captain Ramón Arnaud; his wife, Alicia; and a hundred civilians to Clipperton Island in the Pacific, to secure its copious quantities of “white gold”—bird guano, then prized as fertilizer, which the United States, England, and France had been competing over. Forgotten after the start of the Mexican Revolution and the outbreak of World War I, stranded without supplies for years on end, the Mexicans succumbed to starvation and scurvy, or drowned in pursuit of hallucinatory ships. In 1917 only a handful of women and children remained, along with one man, Victoriano Álvarez, the lighthouse keeper, who declared himself the island’s king and set about raping and killing. It was only on the day the surviving women managed to join forces and dispatch Álvarez with a hammer that the good ship Yorktown arrived to save them. Barrera presents this as an extreme tale of how the isolation of lighthouse keeping might drive a man mad, though of course grand illusions, rape, and murder are just as easily found inland.

In any case, universality is key to the charm of Barrera’s subject. She’s aware of the lurking dangers of sentimentality, and of how unoriginal her lighthouse obsession is. It’s oddly cheering to know, while you fantasize about escaping everybody else, that most all of them are thinking the very same thing.

“Untitled (Banjo),” by Man Ray © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society, New York City/ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Katherine Jackson French: Kentucky’s Forgotten Ballad Collector (University Press of Kentucky, $50), by the music professor Elizabeth DiSavino, explores an equally popular fantasy, about unearthing living chunks of the past in some remote place. Jackson French, a well-to-do Southern woman, was studying for a doctorate in literature at Columbia University when she heard of the rich tradition of balladry in Kentucky’s eastern mountains. She traveled there with a wagon and team of mules in 1909; according to DiSavino, Jackson French’s findings—neglected until now—offer a different view from that put forward by the later and reigning scholar of Appalachian ballads, the Englishman Cecil Sharp. He argued, based partly on the pentatonic scales in the music, that the songs he and his coauthor Olive Dame Campbell encountered represented an Anglo-Saxon form that had been brought to America and survived for centuries in the backwoods, unspoiled by outside influences. As usual in such ballads—satirized memorably by Tom Lehrer in his faux folk song detailing the methods of a young woman who murdered her entire family, leaving only “occasional pieces of skin”—the wit is mordant and the body count is high. Lovers, spouses, and rival siblings fling each other off cliffs into the sea or run one another through with penknives. The closest you generally get to a happy ending (for music fans at least) is when a troublesome beauty’s tresses are retrieved from her watery grave and used to string a harp.

On her initial trip, Jackson French did find communities “cut off from modernity,” in DiSavino’s words, whose frames of reference included figures from Celtic mythology but little from later literary traditions. She visited towns called Sassafras, Viper, and Cut Shin Creek, attending funerals that had been delayed for months by inclement weather, driving up dry creek beds where there were no roads, and being welcomed into hovels, including a log cabin whose unfinished, smoke-blackened walls were pasted over with sheets of newspaper. People sang for her and played fiddles and dulcimers; one boy used knitting needles on the neck of his banjo. A woman shared her written collection of “ballets,” passed down through her family from the generation that settled Kentucky early in the nineteenth century. Another was able to sing a (deeply anti-Semitic) song that Jackson French knew from Chaucer.

What she witnessed was a livelier musical tradition than that described by Sharp. She gave far more credit to Appalachian women for preserving and performing the music; she observed that they were

keener in picturing the tragic situation and in sympathizing with the crying out of the soul of the woman in the ballad. The mother’s monotonous environment and condition of life make the story seem both natural and true.

Had Jackson French succeeded in publishing her results, DiSavino argues, the study of Appalachian balladry might have been redirected from mythologizing about racial purity into something more accurate and inclusive. This seems to require some wishful thinking (Jackson French, too, had plenty to say on balladry as “an immemorial record of the pure ancestry of the singer . . . the spirit and sap of the stock”). Yet the counterfactual scenario DiSavino invokes, in which mountain women and African-American string bands were granted their rightful, central place in early country music, is heartening to entertain.

There are nastier pleasures to be had in the Italian novelist Curzio Malaparte’s non-fiction account of his social life in 1947 and ’48, Diary of a Foreigner in Paris (NYRB Classics, $23.95, translated by Stephen Twilley), which is inflected by Malaparte’s characteristically sly, acid tone, and by the creeping neediness and affront he feels when treated coolly by the French upper crust. Not a sufficiently loyal Fascist to avoid several spells in jail under Mussolini, Malaparte was nevertheless Fascist enough to rouse suspicion in France just after the Resistance. Having spent periods of his youth in Paris, first after fighting in the French Foreign Legion and later as a diplomat, he was evidently keen to reestablish his credentials as a friend to the country—and to give some impertinent advice while he was at it. His postwar turn left might brand him an opportunist, but he reads more as a cynical aesthete, a sophisticate eager to puncture bien-pensant hypocrisies and reinflate them as absurdist entertainment.

There’s far less horror here than in The Skin, the novel of life in Naples under the American liberator-occupiers that Malaparte was working on in the same period and would publish in 1949. Malaparte’s clear-eyed treatment of desperate Neapolitans selling themselves and their children, and his weirdly affectionate caricature of the crass, exploitative American soldiers in love with their own innocence and superiority, still reads as shocking, bracing, more than half a century later. In comparison, this diary, with its generalizations about national character, goes soft at times, but it provides a usefully unromantic portrait of the era’s ideological realignments, in which many scrambled for the moral high ground, and it’s full of sharp jabs at the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. Malaparte is particularly pained by other people’s poor taste in clothes, and even has an anecdote about being dragged before Mussolini himself and upbraided for gossiping about Il Duce’s neckties. (“Will you permit me to say a final word in my defense?” Malaparte claims to have asked en route to the exit. “You’re wearing an ugly tie today as well.”)

Malaparte’s gift for the set piece, which made The Skin so memorable, is apparent here, too. Over several pages, he conjures the Count and Countess Pecci-Blunt, who gave a lavish ball in Rome every season, until in 1938 they fell afoul of Italy’s new racial laws (the countess being of Jewish origin). The guests all cancel overnight, abandoning them. Only Malaparte and one other friend show up, but they hide, not wanting to embarrass the hosts, and watch as the two feast and enjoy fireworks and an elaborate naval battle staged on a lake. A live orchestra strikes up a tune,

caressing the tree leaves wet with dew, the grass and the naked shoulders of the statues. It was a Chopin waltz, whispered by violins and occasionally accompanied by a raspy saxophone in a cypress grove.

The couple, surrounded by empty tables, begin to dance. The pathos of this scene reminded me of Zach Wells’s observation about Ciudad Juárez. The mind cannot process mass killings as it can the story of one or two individuals under threat—it’s easier to take in tragedy a little at a time. Less generously, one might say that this is the level at which Malaparte could empathize with the victims of Fascism, and make his readers feel its bite: a devastating social snub, weathered with grace by people who, no matter how bad things get and how few friends stand by them, are always impeccably dressed.