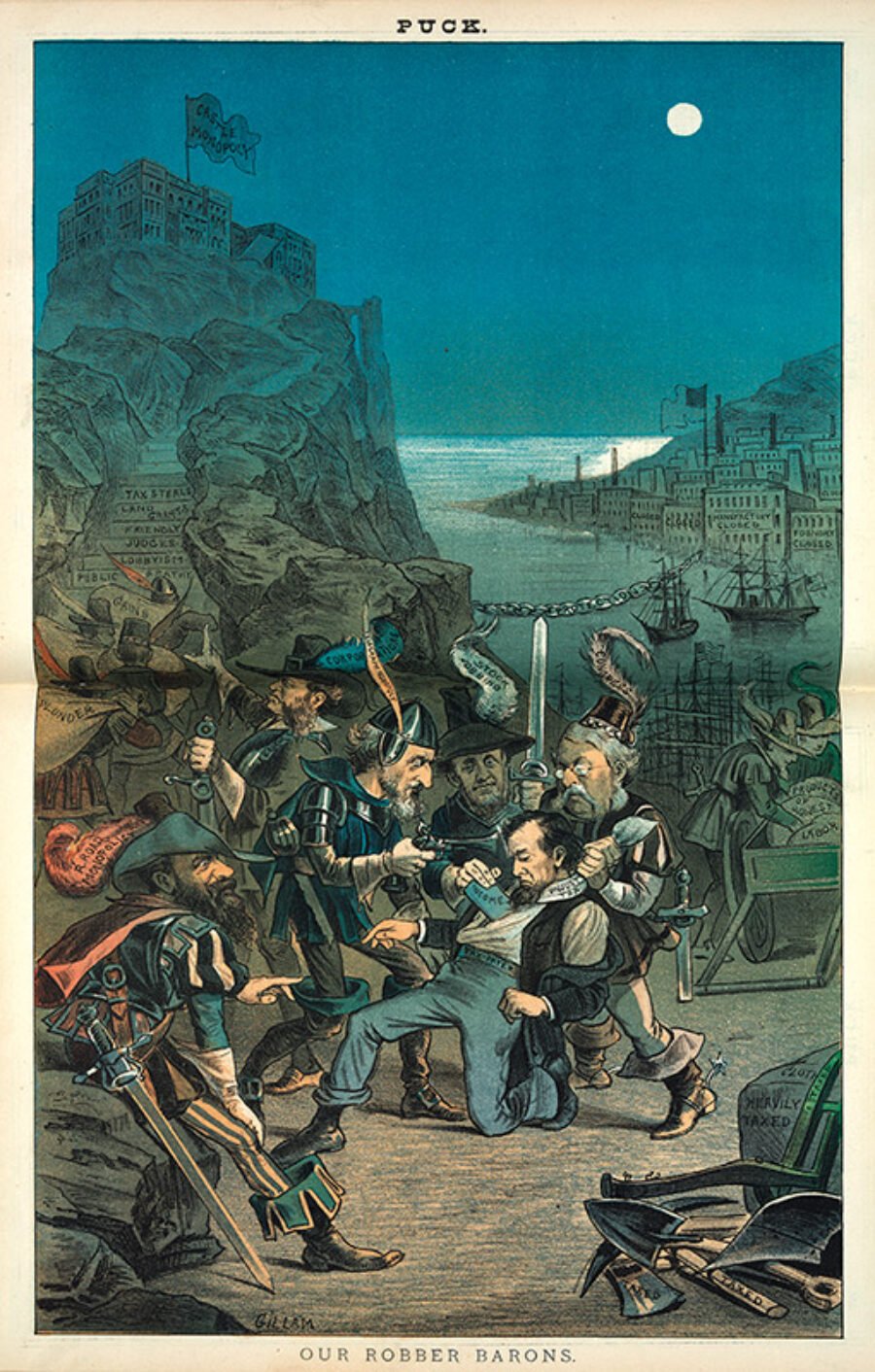

Our Robber Barons, by Bernhard Gillam, from the June 14, 1882, issue of Puck, with Jay Gould as r. road monopolist, William H. Vanderbilt as corporations, Cyrus W. Field as telegraph monopoly, Russell Sage as stock jobbing, and George M. Robeson as congress robbing a tax payer of his income. Courtesy Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington

Just a few short years ago we Americans knew what we were doing: making the world into one big likeness of ourselves. We had the experts; we knew how it was done. Our policy operatives would deradicalize here and regime-change there; our economists would float billions to the good guys and slap sanctions on the bad; and pretty soon the whole place was going to be stately and neat, safe for debt instruments and empowerment seminars, for hors d’oeuvres in the embassy garden and taxis hailed with smartphones. Democracy! Of thee we sang.

Now we stand chastened, humiliated, bewildered. Democracy? We tremble to think of what it might do next.

Government of the people? When we open the door to ordinary people—let them actually influence what goes on—they insist we make bigotry and persecution into our great national causes.

Government by the people? When we let the people have their say—unmanaged, uncurated—they choose the biggest blowhard on TV to be our leader. Then they cheer for him as he destroys the environment and cracks down on immigrant families.

Heed the voice of the plain people and all the levees of taste and learning will immediately be swamped. Half of them will demand that minorities be consigned to the back of the bus; the other half will try to confiscate the hard-won wealth of society’s greatest innovators.

So goes the wail of the American leadership class as they endure another year of panic. They know on some level that what has happened in Washington isn’t due to majority rule at all, but to money and gerrymandering and the Electoral College and decades of TV programming decisions. But the anxiety cannot be dislodged; it is beyond the reach of reason. The people are out of control.

“Populism” is the word that comes to the lips of the respectable and the highly educated when they perceive the global system going haywire. Populism is the name they give to the avalanche crashing down on the Alpine wonderland of Davos. Populism is what they call the mutiny that may well turn the supercarrier America into a foundering wreck. Populism, for them, is a one-word evocation of the logic of the mob: it is the people as a great rampaging beast.

What has happened, the thinkers of Beltway and C-suite tell us, is that the common folk have declared independence from the experts and, along the way, from reality itself. And so they the learned must come together to rescue civilization: political scientists, policy wonks, economists, technologists, CEOs, joining as one to save our social order. To save it from populism.

This struggle has a fundamental, almost biblical flavor. It is a battle of order against chaos, education against ignorance, mind against appetite, enlightenment against bigotry, culture against barbarism. From TED talk to red carpet, the call rings forth: Democracy must be controlled . . . before it ruins our democratic way of life.

The aim is not merely to resist President Donald Trump, the nation’s thinkers say. Nor is the conflict of our times some grand showdown of left and right. No, today’s political face-off pits the center against the periphery, the competent insider against the disgruntled sorehead. In this conflict, the side of moral right is supposed to be obvious. Ordinary people are agitated—everyone knows this—but our concern must lie with the well-being of the elites whom the people threaten to topple.

This is the core assumption of what I call the Democracy Scare: if the people have lost faith in the ones in charge, it can only be because something has gone wrong with the people themselves. As Jonathan Rauch, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a contributing writer at The Atlantic, put it in the summer of 2016: “Our most pressing political problem today is that the country abandoned the establishment, not the other way around.”

Denunciations of populism have been commonplace for years, but they flowered into a full-blown panic in 2016, when commentators identified it as the secret weapon behind the unlikely presidential bid of the TV billionaire Donald Trump. Populism was also said to be the mysterious force that had permitted the self-identified outsider Bernie Sanders to do so well in the Democratic primaries. Populism was also the name of the mass delusion that was leading the United Kingdom out of the European Union. Indeed, once you started looking, unauthorized troublemakers could be seen trouncing rightful ruling classes in countries all around the world. Populists were misleading people about globalization. Populists were saying mean things about elites. Populists were subverting traditional institutions of government. And populists were winning.

In basing our civilization on the consent of the plain people, it suddenly seemed, our ancestors had built on a foundation of sand. democracies end when they are too democratic, blared the title of a much-discussed essay by Andrew Sullivan in which the author applied his grad school reading of Plato to the 2016 campaign. Around the same time, an article in Foreign Policy expressed it more archly: it’s time for the elites to rise up against the ignorant masses.

Then came the unthinkable: the ignorant demagogue Trump was elected to the most powerful office in the world. His victory that November happened thanks to the Electoral College, an anti-populist instrument from long ago, but this irony quickly receded into the background. Although Trump had not actually won over a majority of the people, the Democracy Scare developed into a kind of hysteria. Across the world panels and convenings and academic projects dedicated themselves to analyzing and theorizing and worrying about this thing called populism.

A 2017 global report from Human Rights Watch was titled, bluntly, the dangerous rise of populism. In March of that year, former British prime minister Tony Blair rang the alarm with a New York Times essay titled how to stop populism’s carnage. He also founded the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, an organization whose website announces that populists “can pose a real threat to democracy itself.”

The Democracy Scare has been impressively pan-partisan. The liberal Center for American Progress came together in 2018 with its Beltway nemesis, the conservative American Enterprise Institute, to issue a report on “the threat of authoritarian populism” and to outline “the task facing America’s political elites,” which was to beat it back.

Populism works, these authorities assure us, by summoning up the worst features of democracy. It puts the common man on a pedestal; it promises him the strong leaders he craves; and it assaults the multiculturalism he hates. When populists come to power, they ignore norms and attack institutions that protect basic rights like free speech and the presumption of innocence. Simply defined, populism is the ism that goes with mob rule. It’s the headlong collapse into the tyranny of the majority that our Founding Fathers so dreaded.

Populist parties are “particularly prone to internal authoritarianism,” writes political scientist Jan-Werner Müller, since they believe there can be only one way of representing the people. For the same reason, populists are said to be suspicious of the media. They are would-be tyrants, claiming “that no action of a populist government can be questioned” because, of course, it’s really the action of the people. And populists are always hinting at a “massive disenfranchisement” of those parts of the population of which they don’t approve.

The movement is also said to be unavoidably hostile to intellectuals and ideas; this is said to be its most critical failing. It is a “celebration of ignorance,” as one pundit put it in the Financial Times. It fails because it regards “the voice of ordinary citizens . . . as the only ‘genuine’ form of democratic governance,” as a 2019 book on “Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism” tells us, “even when at odds with expert judgments—including those of elected representatives and judges, scientists, scholars, journalists and commentators.”

Thus the tragic flaw in the populist approach: its ideal of government of, by, and for the people doesn’t take into account the ignorance of the actual, existing people. The people can’t find Syria on a map; they think God created humans in one day in their existing form; and if you give them the chance, they will go out and vote for a charlatan like Trump.

This is what made the election of 2016 a veritable “dance of the dunces,” according to the Georgetown political philosopher Jason Brennan’s book Against Democracy, an accounting of the ignorance of the average American that offers hints about how an enlightened modern government might, in effect, disenfranchise the stupid and so deal with the problem of democratic error.

There’s something peculiar about all this. The English language provides a great many solid choices for someone wishing to describe a leader who plays on mob psychology or racial intolerance. “Demagogue” is an obvious one, but there are others—“nationalist,” “nativist,” “racist,” or “fascist,” to name a few. They are serviceable words, all of them. In the feverish climate of the Democracy Scare, however, none of those will work: “populist” is the word we are instructed to use. “Populists” are the ones we must suppress.

Let’s find out why.

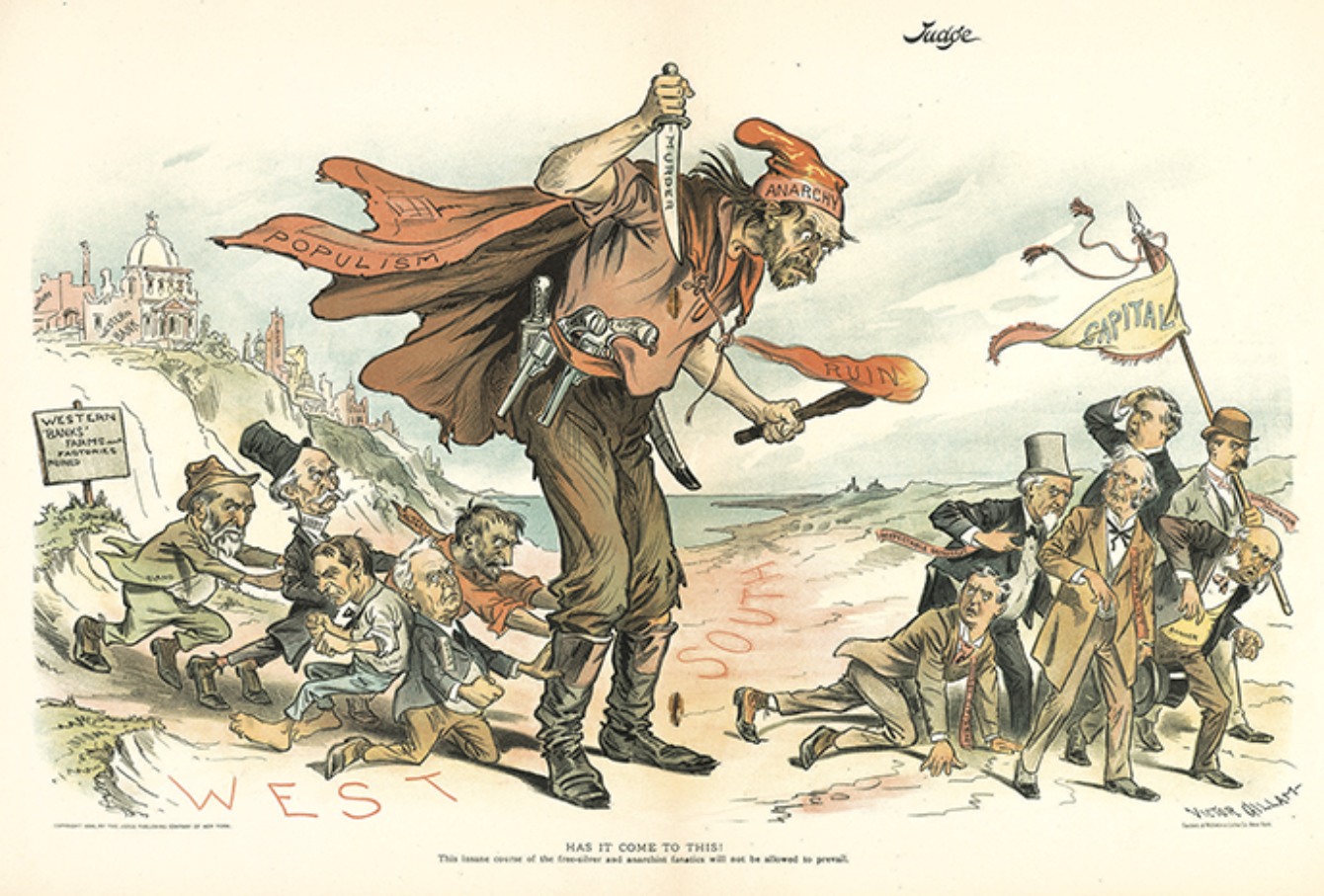

Has It Come to This, by Victor Gillam, from the August 8, 1896, issue of Judge

Drive the highway between Kansas City and Topeka and you will pass through a landscape of peaceful, rolling hills (and occasional scenes of violent tornado damage). In the fertile valley of the Kansas River, the farms are raising corn and soybeans; through the fields run the tracks of the old Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway.

It was somewhere in this bucolic setting that the controversial word “populist” was invented. There are no historical markers to indicate exactly where the blessed event took place, but nevertheless it happened—in this stretch of green countryside, on a train traveling from K.C. to Topeka—one day in May 1891.

Could they have peeked into the future, that group of Topeka-bound passengers would have been astonished by the international reach and malign interpretations of their deed. That they were inventing a noun signifying “mob-minded hater of all things decent” would have come as a complete surprise to them. By coining the word “populist,” they intended to christen a movement that was brave and noble and fair—that would stand up to the narrow-minded and the intolerant.

The People’s Party was the official moniker of the organization these men nicknamed, and it was one of America’s first great economic-political uprisings, a quintessential mass movement, in which rank-and-file Americans learned to think of the country’s inequitable economic system as a thing they might change by common effort. The party offered a glimpse of how citizens of a democracy, born with a faith in equality, could react when the brutal hierarchy of conventional arrangements was no longer tolerable.

It was also our country’s final serious effort at breaking the national duopoly of the Republicans and Democrats. In the 1890s, the two main parties were still largely regional organizations, relics of the Civil War; the People’s Party’s innovation was to make an appeal based on class solidarity, aiming to bring together farmers in the South and the West with factory workers in Northern cities. “The interests of rural and civic labor are the same,” proclaimed the 1892 Omaha Platform of the People’s Party, and “their enemies are identical.” By which the party meant those who prospered while making nothing: bankers, railroad barons, and commodity traders, along with their hirelings—corrupt politicians who served wealth instead of the people.

This bid for reform came during a period of unregulated corporate monopolies, in-your-face corruption, and crushing currency deflation—and also during a time when everyone who was anyone agreed that government’s role was to provide a framework conducive to business and otherwise to get out of the way. That was the formal ideal; the execution was uglier—a matter of deception and exploitation, bankruptcy and foreclosure, of cabinet seats for sale and entire state legislatures bought with free-ride railroad passes.

At the time, America was still largely an agricultural nation, and in many places farmers made up overwhelming majorities of the population. In the South, they tended to be desperately poor and heavily reliant on bankers, landowners, and shopkeepers. In the West, farmers found themselves at the mercy of a different set of middlemen—local railroad monopolies and far-off commodity speculators. Like their brethren in the South, they worked and borrowed and grew and harvested; they watched as what they produced was sold in Chicago and New York for good prices; and yet what they themselves earned from their labors fell and fell and fell.

In the 1880s, these farmers started signing up by the millions for a cooperative movement called the Farmers’ Alliance. To such people the Alliance made a simple proposition: let’s find out why we are being ruined, and then let’s get together and do something about it. Education was the first order of business, and the movement conceived of itself as a sort of national university, employing an army of traveling lecturers. The Alliance also promised real results for farmers, by means of rural cooperatives and political pressure. It demanded the regulation of railroads, federal loans to farmers, and currency reform of a kind that would help debtors.

Along the way, something profound took place. The farmers—men and women of society’s commonest rank—figured out that being exploited was not the natural order of things. So they began taking matters into their own hands. In Kansas and a few other Western states, members of the group went into politics directly, and the People’s Party was born.

The farmers’ revolt against the existing two-party system quickly spread to other states, and other labor-oriented reform groups began signing on. This brings us to that auspicious day in May of 1891. Early that month, a delegation of Kansans had attended a convention in Cincinnati and formally launched their People’s Party at the national level. By the time those reformers boarded the train home to Topeka, their movement looked to have a promising future: they had a platform, a cause, millions of potential constituents, and the ringing Jeffersonian slogan “Equal rights to all, special privileges to none.”

One thing the insurgent party did not have, however, was a catchy word to describe its adherents, and so, on that fateful train ride—and in conversation with a local Democrat who knew some Latin—they came up with one: “populist,” derived from populus, meaning “the people.”

The name’s likely debut in print followed immediately. The May 28, 1891, edition of the American Nonconformist and Kansas Industrial Liberator, a radical newspaper out of Winfield, used the new word as part of its excited coverage of the Cincinnati proceedings:

There must be some short and easy way of designating a member of the third party. To say, “he is a member of the People’s Party” would take too much time. Henceforth a follower and affiliator of the People’s Party is a “Populist”; for a new party needs and deserves a new term.

At the time of its premiere, “populist” was a term without ambiguity. It referred to economic radicals like Leopold and Henry Vincent, the two brothers who ran the American Nonconformist. Populists were those who supported a specific list of reforms designed to take power away from “the plutocrats” while advancing what the Vincent brothers called “the rights and needs, the interests and welfare of the people.” In the same issue of the paper, the Nonconformist spelled out the grievances of the People’s Party: it protested poverty, unbearable debt, monopoly, and corruption, and it looked ahead to the day when these were ended by the political actions of the people themselves. “The industrial forces have made a stand,” the paper declared of the events in Cincinnati. “The demands of the toilers for right and justice were crystallized into a strong new party.”

In fact, the Populist revolt against the two major parties would turn out to be even more momentous than that grandiose passage implied. The People’s Party was one of the first in a long line of political efforts by working people to tame the capitalist system. Up until then, mainstream politicians in America had by and large taken the virtues of that system for granted—society’s winners won, those politicians believed, because they were better people, because they had prevailed in a rational and supremely fair contest called free enterprise. The Populists were the ones who blasted those smug assumptions to pieces, forcing the country to acknowledge that ordinary Americans were being ruined by an economic system that in fact answered to no moral laws.

Not everybody thought Populism was such a wonderful invention. Kansas Republicans—whose complacent rule over the state the People’s Party rudely interrupted—insisted that a better term for their foes was “Calamityites,” because they complained all the time. The Kansas City Star, an influential regional paper, surveyed the Cincinnati convention where the party was born and sneered that it “bore a much closer semblance to a mob than to a deliberative assembly.” What’s more, the Star’s editorialist continued, “The conference, from beginning to end, was distinguished for its intolerance and extreme bigotry.”

The judgment of the Topeka Daily Capital, the leading voice of Republican rectitude in Kansas, was even harsher. The paper’s lively front-page news story on the gathering in Cincinnati was headed as follows:

third party!

Cincinnati Rapidly Filling Up With the Disgruntled Ravelings of the Old Parties

kansans to the fore

In Large Numbers and Making Themselves Ridiculously Conspicuous by Their Gab

hayseed in their hair

Kansas Alliancers Proclaim Their Politics by the Uncouthness of Their Personal Attire

This is how the Establishment welcomed the Populist revolt into the world, and this is pretty much how the establishment thinks about populism still.

From the very beginning, then, “populism” had two meanings. There was Populism as its proponents understood it: a movement in which ordinary working people demanded democratic economic reforms. And there was Populism as its enemies characterized it: a dangerous movement of groundless resentment in which demagogues led the disreputable.

The specific reforms for which the People’s Party campaigned are largely forgotten today, but the insults and accusations with which Populism was received in 1891 are alive and well. You can read them in best-selling books, watch them flashed on PowerPoints at prestigious foundation conferences, hear the long-ago denunciations of the Kansas City Star and the Topeka Daily Capital echoed by people who have never heard of Topeka: Populist movements, they will tell you, are mob actions; reformers are bigots; their leaders are blatherskites; their followers are mentally ill, or ignorant, or uncouth at the very least. They are cranks; they are troublemakers; they are deplorables. And, yes, they still have hayseed in their hair.

The name I give to this disdainful reaction is “anti-populism,” and when you investigate its history, you find its adherents using the same rhetoric over and over again. Whether defending the gold standard in 1896 or NAFTA in 2016, anti-populism mobilizes the same sentiments and draws on the same stereotypes; it sometimes even speaks to us from the same prestigious institutions. Its most toxic ingredient—a highbrow contempt for ordinary Americans—is as virulent today as it was in the Victorian era.

The first item in anti-populism’s bill of charges is that populism is nostalgic or backward-looking in a way that is both futile and unhealthy. Among the many public figures who have seconded this familiar accusation is none other than Barack Obama, who in 2016 criticized unnamed politicians for having “embraced a crude populism that promises a return to a past that is not possible to restore.”

Obama’s understanding of “populism” as a politics of pointless pining for bygone glories—exemplified by Trump’s slogan, “Make America Great Again”—is unremarkable, but as a description of the agrarian radicals of the late nineteenth century it would be largely without foundation. As modern historians remind us, the Populists believed in progress and modernity as emphatically as did any big-city architect or engineer of their day. Their newspapers and magazines loved to publicize scientific advances in farming techniques; one of their favorites was a paper called the Progressive Farmer. For all its gloom about the plutocratic 1890s, the Populists’ rhetoric could be surprisingly optimistic about the potential of ordinary people and the society they thought they were building.

Anti-populism is similarly misleading on the matter of international trade. In a 2017 paper about the “populist backlash of the late nineteenth century,” the Hoover Institution historian Niall Ferguson tells us flatly that hostility to free trade has always been among the defining features of populism, because populism is always a “backlash against globalization.” Lots of other scholars say the same thing: William Galston of the Brookings Institution, for example, tells us that populism has always been “protectionist in the broad sense of the term” and that all forms of populism stand “against foreign goods, foreign immigrants, and foreign ideas.”

Were we to apply these arguments to Gilded Age America, they would be almost entirely upside-down. If you examine where the parties stood on the issue of tariffs, you find that the era’s great champions of protectionism were in fact big business and the Republicans. William McKinley, the man responsible for crushing the People’s Party, first rose to fame as the author of the McKinley Tariff, the very definition of a backlash against free trade. It was William Jennings Bryan’s Democrats who were the true-believing free-traders of the period. And it was Populist leaders who dreamed of building a publicly owned railroad running from the Great Plains to the Texas Gulf Coast so that farmers could export to the world without having to pay the high freight rates imposed by private railways.

So it goes time and again with our contemporary anti-populists: when their denunciations are compared with the ideas of the people who invented the P-word, the stereotype of populists in general collapses. It does not describe historical reality. The Pops did not fear government, as we are often told populists do; they wanted it to grow big and strong. The Pops did not hate ideas; they meant to spread knowledge to the farthest corners of the land. The Pops were not socially regressive; they were unique among the major parties of their time in boasting numerous female leaders. Again and again, upon investigation, the hateful tendencies that we are told make up this frightful worldview are either absent from historical Populism or are the opposite of what it stood and stands for, or else far more accurately describe the people who hated Populism and who have opposed it ever since the 1890s.

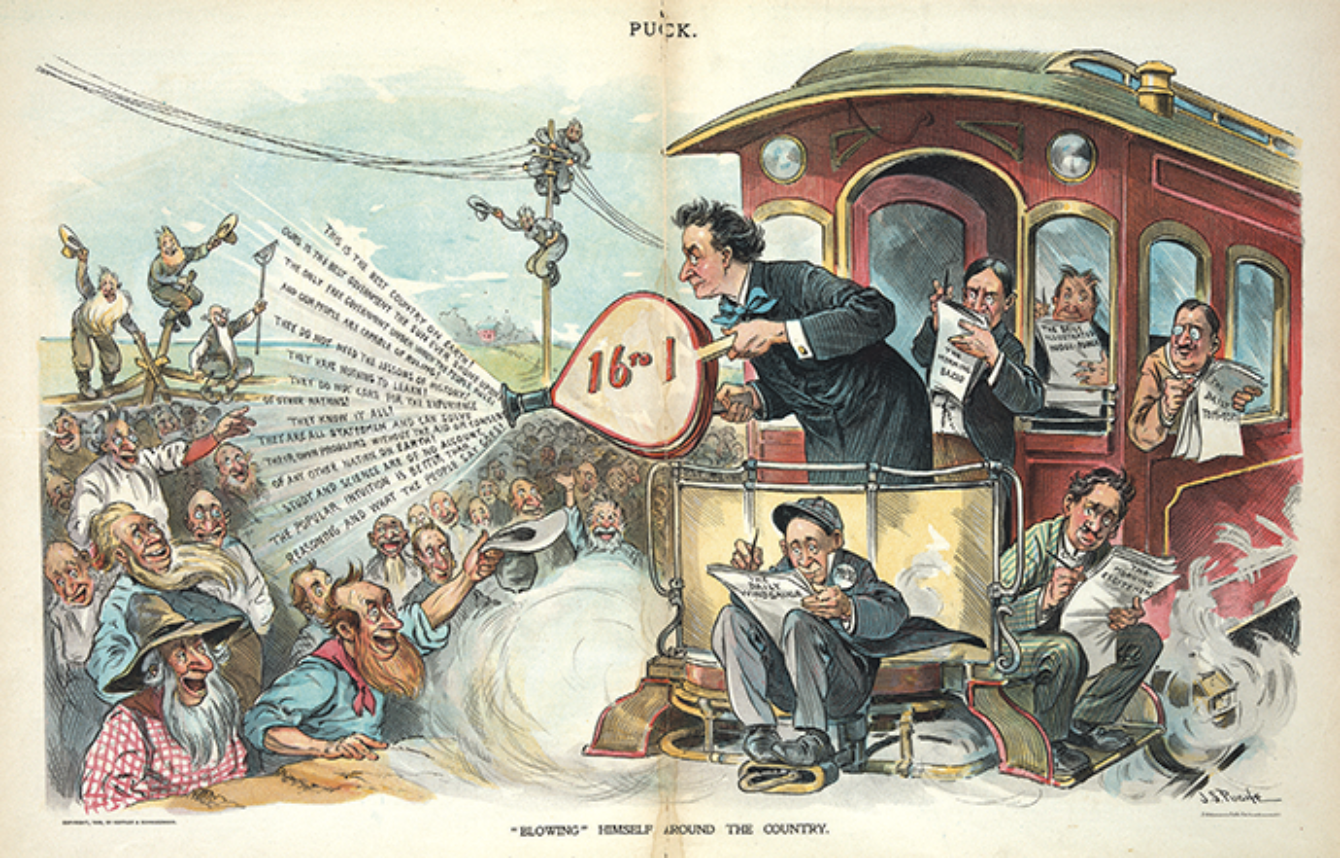

Blowing Himself Around the Country, by J. S. Pughe, from the September 16, 1896, issue of Puck

Courtesy Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington

Of course, language is mutable. Merely figuring out the intentions of the people who coined a given word doesn’t tell us a whole lot. But while the People’s Party is no more, the political philosophy that the Populists embodied did not die. The idea of working people coming together against economic privilege lives on; you might say it constitutes one of the main streams of our democratic tradition.

The populist impulse has been a presence in American life since the country’s beginning. Populism triumphed in the 1930s and 1940s, when the people overwhelmingly endorsed a regulatory welfare state. Populist uprisings occur all the time in the United States, always against the same enemies—monopolies, banks, elites, and corruption—and always with the same type of salt-of-the-earth heroes. The most obvious embodiment of the populist tradition today is certainly the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign, whose principal likes to describe it as a “grassroots movement” rising up against the nation’s grotesque economic inequality.

That is the word’s historical meaning, and when we use it as a handy term for demagogues and would-be dictators, we are inverting that definition. Populism in its original formulation was profoundly, achingly democratic; it was also, by the standards of the time, anti-demagogic, pro-enlightenment, and pro-equality. In its heyday, and alone among American political parties of the time, the Populists stood strong for human rights. Populism had prominent female leaders. Populists despised tyrants and imperialism. Although not entirely immune to the racialism of its era, Populism defied the poisonous idea of Southern white solidarity.

In these days of feverish anti-populism, my mind often goes back to a 1900 speech by one of the very last Populists in Congress, a Nebraska lawyer named William Neville. His subject was America’s imperial rule over the Philippines, and his party’s opposition to it. But first he denounced both Southern Democrats, for trying to “exclude the black man from the right of suffrage,” and Republicans, for “shooting salvation and submission into the brown man because he wants to be free.” Then Neville said this:

Nations should have the same right among nations that men have among men. The right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is as dear to the black and brown man as to the white; as precious to the poor as to the rich; as just to the ignorant as to the educated; as sacred to the weak as to the strong; and as applicable to nations as to individuals. And the nation which subverts such right by force is no better governed than the man who takes the law in his own hands.

Of course, scholars and pundits have a right to ignore such statements and to divorce any word they choose from its original meaning. It’s legitimate for them to take the term “populist” back to its Latin root and start all over again from there, to pretend that the train from Kansas City never arrived and the farmers’ revolt never happened.

But why do that? Why use such a fine, democratic word to mean “racist,” to mean “dictator,” to mean “anti-intellectual”?

The answer is that denunciations of populism like the ones we hear so frequently nowadays are part of a long tradition of pessimism about popular sovereignty and democratic participation. And it is that tradition of quasi-aristocratic scorn, rather than populism itself, that has allowed the paranoid right to flower so abundantly in our time.

Perhaps we should not be surprised to discover that modern-day thinkers who attack what they call populism only rarely bother to consider the movement that invented the word. Far more frequently they attach the term to the deeds of European politicians like the Le Pen family or the rhetoric of certain South American demagogues. Some of these experts seem unaware that the People’s Party of the 1890s existed. Others mention it only in passing.

What these present-day thinkers cannot escape are the roots of their own anti-populist tradition. Whether or not they have ever heard of Kansas Populists like “Sockless” Jerry Simpson, they are embracing a political philosophy that was pieced together long ago to stop radicals like him.

The anti-populist tradition came into its horrific own during the 1896 Democratic National Convention, when working-class unrest appeared to triumph in the person of William Jennings Bryan, then a young former congressman from Nebraska, who won the presidential nomination on the strength of his oratory against the gold standard. Bryan talked a lot like a Populist, and a short while after the Democratic convention, the Populists nominated him as well. To the Establishment, there could be no doubt about what this signified: one of the nation’s main political parties had been captured by radicalism, and the shock was as great as that of a stock-market crash. Before 1896, the differences between Democrats and Republicans on economic questions had been small; the two parties orbited each other within a tight system of limited government, gold-backed money, and friendliness toward big business. Bryan’s nomination signaled this arrangement’s collapse.1

The country was in a recession that year, which was the inescapable theme of the campaign, but the candidates addressed it via the proxy issue of the U.S. dollar. Democrats and their Populist allies blamed the deflationary gold standard for the unhappy fate of farmers. William McKinley and the Republicans believed the gold standard to be the central pillar of civilization itself, and regarded the threat to dismantle it as a deadly peril. The Republicans were wrong on this issue, but nevertheless they prevailed. They contrived to crush Bryan’s challenge and, in so doing, to build a lasting stereotype of reform as folly. The word with which they expressed that stereotype: “populism.”

Let us open the Judge magazine of August 8, 1896, to get a glimpse of how respectable Americans regarded the radical threat. Judge was one of the country’s premier humor magazines, with several large, beautifully drawn political cartoons in each issue. The rest of its pages typically featured grotesque caricatures of blacks, Irish, Jews, immigrants, and farmers. Between the jokes at the expense of these subordinate people, one could also catch glimpses of the demographic for whose amusement the chuckles were collected: refined, upper-class whites—people of manners and education and bank accounts—saying witty things about the burdens of good taste.

With this particular number of Judge, however, it is clear that something terrible has happened: the usual tone of genial mockery has given way to panic. At the magazine’s center is a foldout illustration of stark American disaster, brought on by a gigantic figure labeled populism. This colossus is rustic and tattered, but we are not meant to laugh at him: he glares with predatory eyes, he is armed with a brace of pistols and knives, he wears a Phrygian cap—the liberty cap of the French Revolution—marked anarchy, he wields the torch of ruin, and he towers terrifyingly over his fellow Americans. From this monster flee the sort of tidy white people who made up Judge magazine’s readership: banker, capitalist, honest citizen, respectable democrat. One of them cowers on the ground beneath Populism’s onslaught; another clutches his head in disbelief. “Has It Come to This!” blubbers the caption.

This was the Democracy Scare, 1896 version: our system was unraveling, with society’s worst elements rising up against its best. Similarly frightful images appeared that year wherever people were dignified and accomplished together, always expressed in the vocabulary of hysteria and hyperbole. Populism wasn’t merely menacing “norms”; it was bringing the country face-to-face with anarchy and repudiation.

On July 10, the New York Sun declared that the Democratic Party had been given over to “Jefferson’s diametric opposite, the Socialist, or Communist, or, as he is now known here, the Populist.” A lead editorial that ran in the Sun a few days later declared that there was no real Democratic candidate that year. Instead, “there are Populist-Anarchist candidates nominated on a Populistic-Anarchist platform.” Similarly, in a pamphlet distributed by the Republican Party that fall, the novelist and statesman John Hay claimed that the Democrats no longer existed: “The enemy which confronts us is the Populist party,” which had swallowed the Democrats “as a python might swallow an ox.”

Then as now, consensus among elites was the primary weapon of the anti-populist resistance. Thanks to William Jennings Bryan and “his new Red Circus,” something miraculous had happened, the Sun proclaimed: “the business interests of the country are all arrayed on one side.” E. L. Godkin, then the conscience of American journalism, clucked in The Nation that “no man has ever yet been elected President whom the business interests of the country . . . distrusted and opposed as unsafe; these interests in the controlling states are substantially unanimous against Bryan.” Godkin was pleased even better by the harmony with which the nation’s press came together against the Democratic challenger. Similar unanimity reigned in fashionable churches and in prestige academia.

From the heights of this consensus the men of quality denounced the rabble. Bryan’s campaign aroused “the basest passions of the least worthy members of the community,” announced an editorial in the New–York Tribune that ran on the day after the election. “It has been defeated and destroyed because right is right and God is God.”

Populism represented the world turned upside down. It came from a dark place where democracy’s guardrails were gone, where wealth and learning and status counted for nothing. “Populism” was a word used to express the horror of seeing hierarchies collapse and the lowly clamber to places where they did not belong. Populists, John Hay wrote, valued nothing, throwing “their frantic challenge against every feature of our civilization.” They longed to bind the hands of government “where it is inclined to protect order and property.” They appealed “to the openly lawless.” They waged a “shameful insurrection against law and national honesty.” Their plans for funding the government were “the merest babble of the loafers around a rural livery stable.” For the plumèd knights of the Republican Party, it was, he wrote, “as if a champion at a tourney, awaiting the onset of a chivalrous antagonist, should suddenly find himself attacked by a lunatic in rags.”

The familiar identification of populism with demagoguery, a core doctrine of modern-day punditry, is also descended directly from this original Democracy Scare. It began on the very day of Bryan’s surprise nomination. An editorial in the Evening Post declared the Nebraskan to be the Democrats’ “chief demagogue,” a man “who took the mob of repudiators off their feet by a speech of forty-blatherskite power.” It wasn’t so much Bryan’s arguments that won the Democrats over, the editor continued, as it was “his wind power, which is immense.”

A favorite trope of the anti-populists of the 1890s was the masquerade or the put-on. Bryan and his followers were not real Democrats, the men of quality agreed; they were “masquerading in the Democratic garb,” as Cornell’s president, Andrew D. White, put it. In a more gothic vein, Leslie’s Weekly depicted Bryan’s face as a mask, behind which lurked a hideous howling anarchy in a boar’s hide and bat wings. This was, as the caption put it, “The New (Not the True) Democracy Unmasked.” One of the monster’s hands held its name tag, a second gripped the throat of a working man, a third used a knife to cut the dollar in half.

Who was really in control of the uprising? Was Bryan some kind of mastermind, or was he merely the tool of sinister others? According to the New–York Tribune, Bryan was “not the real leader of that league of hell,” a verdict the paper handed down after the Democrat lost the election. “He was only a puppet in the blood-imbrued hands of Altgeld the Anarchist and Debs the revolutionist and other desperadoes of that stripe.”2

And if he wasn’t a puppet or a demagogue—if Bryan wasn’t fooling when he denounced plutocracy—oh my God, don’t even ask. “He is a dangerous man,” editorialized the New York Sun: “If he is sincere, dangerous even as a fool is dangerous when he raises a false alarm of fire in a crowded theatre; and if a demagogue, as he seems to be, doubly dangerous.”

Then as now, faith in the people’s wisdom was thought to be populism’s original sin. Bryan was mocked in The Nation for supposedly starting his speeches with empty salutes to the genius of the common people: “Your wisdom is inexhaustible and infallible,” he was parodied as saying. “I tell you that you are so great that you can ignore the rest of the world.” A cartoon in Puck imagined Bryan on his whistle-stop tour, blowing the same sort of bunkum out of a bellows at a crowd of happy farmers, snaggletoothed idiots wearing long agrarian whiskers. Bryan was driving them to ecstasy by saluting the wisdom of the hayseed:

Our people are capable of ruling!

They do not need the lessons of history!

They have nothing to learn!

They do not care for the experience of other nations!

They know it all! . . . Study and science are of no account,

the popular intuition is better than reasoning and what the people say goes!

That populism is at war with intellect, that it is an offense to meritocracy—these lasting axioms are also rooted in the original Democracy Scare, when Populism threatened to level both the hierarchy of money and that of credentialed technique. The institution where these two came together was the gold standard, the bedrock of both classical economics and the nineteenth-century banking system. For the Populists, the elites’ faith in gold was a favorite target for mockery. But for establishment figures like John Hay, the only legitimate way to settle the currency question was “by the investigations of the leading economists of the world,” gathered in solemn contemplation. The conclusion of such a gathering was certain: one couldn’t adopt a silver standard in just one country and hope to succeed. America’s economy was locked in an international system regulated by responsible expertise, Hay insisted, and upon this reasoning everyone who was anyone agreed. “All the intelligent bi-metallists of America . . . ; all those of England . . . ; all the German scholars . . . agree in this.”3

Many years later, the consensus-minded historian Richard Hofstadter would assert in these pages that Populism reflected status anxiety and even a “paranoid style.” His larger insight, which revolutionized social science in the 1950s and which persists in the anti-populism of our own day, was that mass protest movements in general could be understood as a reaction of maladjusted minds to the advance of modernity.

In truth, Hofstadter’s discovery had already been made back in 1896, when Populism was repeatedly diagnosed as a mental aberration. In September of that year, as the contentious presidential campaign unfolded, the New York Times announced the alarming discovery: William Jennings Bryan appeared to be clinically insane. It began with a letter to the paper from an anonymous “alienist,” or psychologist, who examined Bryan’s heredity, his heretofore mediocre career, and his behavior on the campaign trail, and concluded “without any bias” that “Mr. Bryan presents in his speech and action striking and alarming evidence of a mind not entirely sound.” Proof: the candidate was “an apostle of an economic theory without ever having a training in economics.”

It was a scary situation, the alienist continued. After all, having “a madman in the White House” would not only be dangerous, but would also damage democracy itself, since it “would forever weaken the trust in the soundness of republics and the sanity of the voting masses.”

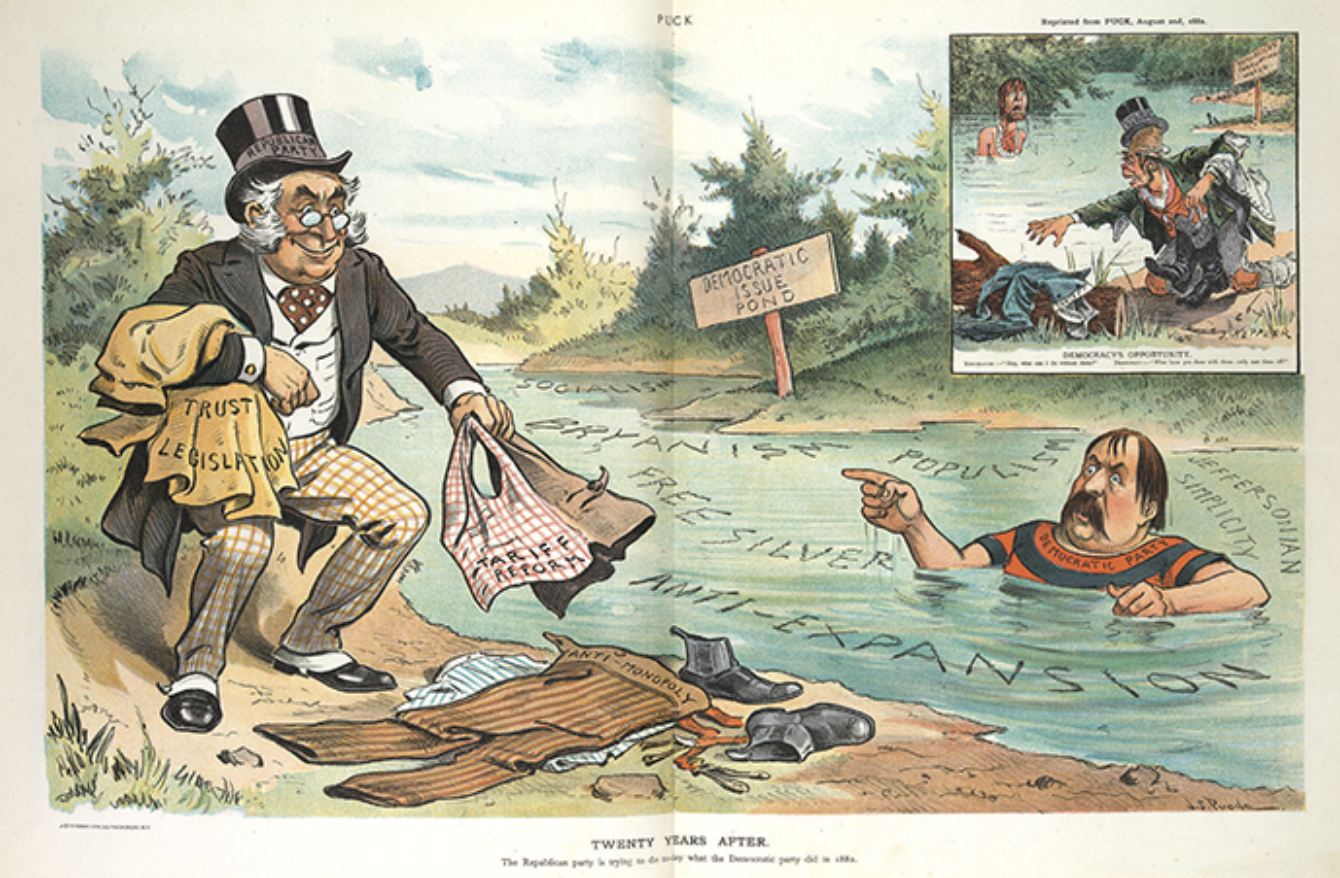

Twenty Years After, by J. S. Pughe, from the November 19, 1902, issue of Puck

Courtesy Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington

Further examples from the bitter, costly campaign of 1896 can be piled up almost without limit, but you get the point: we are in the grip of a remarkably similar distemper today. To be clear, I believe that President Trump richly deserves nearly any criticism he gets. He is not really a populist, and I have no intention of building sympathy for him. But the danger of anti-populism is that it goes far beyond objecting to one vile politician. This was demonstrated in March as the anti-populist establishment came together to pummel the campaign of Bernie Sanders. Whatever its target, anti-populism is always a brief for elite and even aristocratic power, an attack on the democratic tradition itself. That is ultimately what’s in the crosshairs when commentators tell us that populism is a “threat to liberal democracy”; when they announce that populism “is almost inherently antidemocratic”; when they declare that “all people of goodwill must come together to defend liberal democracy from the populist threat.”

These are strong, urgent statements, obviously intended to frighten us away from a particular set of views. Millions of foundation dollars have been invested to put scary pronouncements like these before the public. Media outlets have incorporated them into the thought feeds of the world. Just as in 1896, such ideas are everywhere now: your daily newspaper, if your town still has one, almost certainly throws the word “populist” at racist demagogues and pro-labor liberals alike.

Here is David Brooks, making the connection between “populists of left and right” in a New York Times column denouncing Sanders. The Vermont senator, Brooks asserts, embraces

the populist values, which are different [from liberal ones]: rage, bitter and relentless polarization, a demand for ideological purity among your friends and incessant hatred for your supposed foes.

And here is how The Economist made exactly the same point, whining that Americans may soon be forced to choose

between a corrupt, divisive, right-wing populist, who scorns the rule of law and the constitution, and a sanctimonious, divisive, left-wing populist, who blames a cabal of billionaires and businesses for everything that is wrong with the world. All this when the country is as peaceful and prosperous as at any time in its history. It is hard to think of a worse choice.

As it happens, the men of quality did their job, and working Americans will not face the ignoble prospect of voting for a candidate who takes their side against billionaires and businesses. The larger message of anti-populism, regardless of where it comes from on the political spectrum, is always one of complacency. Elites rule us because elites should rule us. They are in charge because they are the best.

And so we come to understand the real task before us today: to rescue from the enormous condescension of the comfortable the one political tradition that has a chance of reversing our decades-long turn to the right.

This essay is excerpted from The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism, which will be published next month by Metropolitan Books.