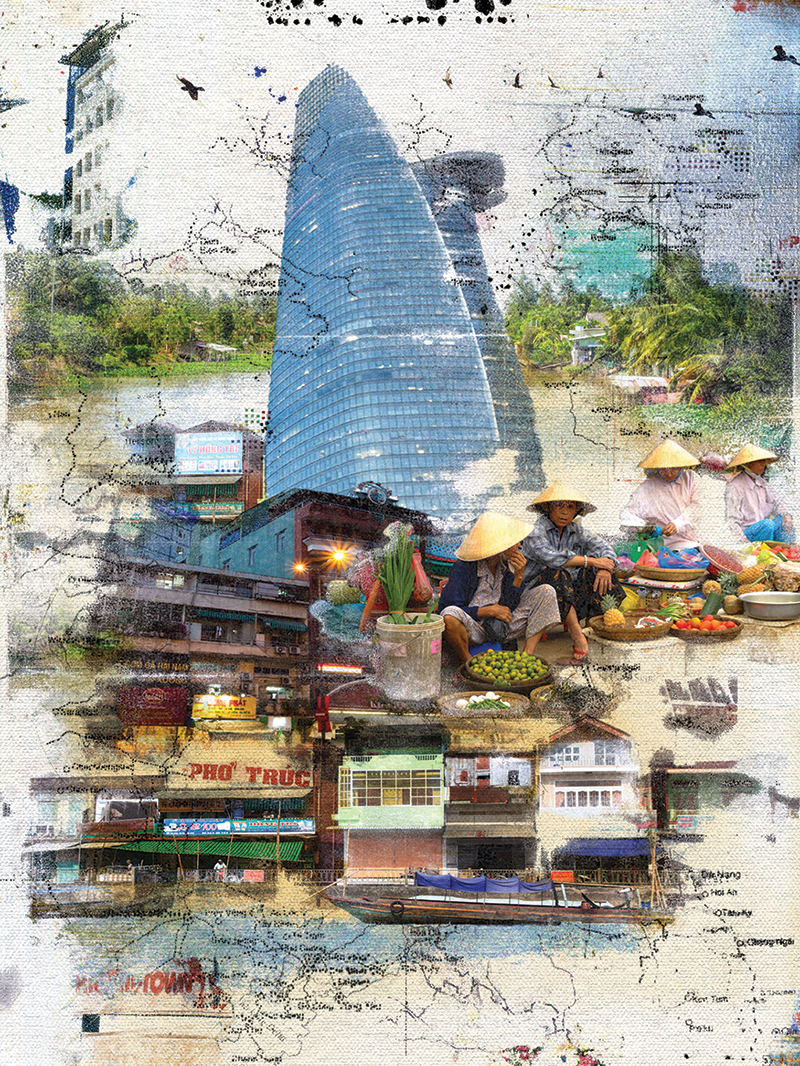

Illustrations by Brian Hubble. Source images: A motorbike taxi driver reading a newspaper in Ho Chi Minh City © Image Professionals GmbH/Alamy; Ho Chi Minh City skyline © John Michaels/Alamy; Mekong Delta © Jason Langley/Alamy

For three years in my twenties, I lived in Vietnam, in Ho Chi Minh City, which most people there still call Saigon. I arrived on February 4, 1995, the same year the United States reestablished diplomatic ties with the country, one it had expended much time and treasure bombing, napalming, saving by destroying, and bludgeoning by attrition, resulting in what optimistic souls like to insist was a tie.

I went to Vietnam originally on a college semester abroad, and stayed on after I graduated, supporting myself by writing articles and working as a copy editor at a government newspaper. This was an important period in my life, which is not all that important. I met my first wife, with whom I have a son. I made lasting friendships with Vietnamese people, very few of whom, I learned, could do much with the name Ted, which is practically unpronounceable to native speakers of Vietnamese. They would make a few attempts. I would correct them, like an asshole, in my mediocre Vietnamese. And then we’d give up.

I had an idea of making a life in Vietnam, as one of those louche forever-pats you would see at Apocalypse Now and Q Bar, two watering holes of the era. I would teach corporate English to private clients and dress in pleated slacks and forget how to say “carabiner” in English. I learned after a while that it did not suit me. But even so, I wanted very badly to connect with my Vietnamese friends, and names are a gateway to that.

I suppose I could have changed mine. My ex-wife, who was born in Vietnam but fled with her family by boat in the 1980s, took an American name when she was a child in the United States. Both of my grandfathers, refugees from Germany and what is now Ukraine, changed their names in the United States. But I was not an immigrant; I was an expatriate, and a white American one at that. My foreignness conveyed what academics describe as an “ethnic advantage,” something from which I had undoubtedly benefited back home but had never felt so keenly before or since. I never seriously considered taking a new name.

Names are powerful. It is no small thing to change one, or to leave it be. Last March, the novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen, who fled Vietnam with his family when he was a child, published an op-ed about his name in the New York Times. His parents had changed theirs, to Joseph and Linda, but he had refused, believing it would cut a “psychic tie” to the country. “I felt, intuitively, that changing my name was a betrayal,” he wrote. “A betrayal of my parents . . . a betrayal of being Vietnamese . . . [a] betrayal, ultimately, of me.” I spoke with Nguyen a few months ago, and I asked him whether he had ever thought of returning to Vietnam. He said he had visited as an adult, but doubted he would ever go back to stay. “I couldn’t imagine being a writer in Vietnam because of the political repression,” he said. “I’m not returning until my books can be published there.”

But there are many Vietnamese Americans who have chosen to return to Vietnam to live, a large portion of whom are refugees who left at the end of the war or who fled by boat in the years after, and even some who were born in the United States. Reverse migration from America is not unique to Vietnamese people. But it is an interesting phenomenon to observe at this particular moment in our country, one in which all manner of “patriots” and bigots, the president among them, are free to question the “Americanness” of our immigrants, in ways many had believed to be banished to history.

Neither of my grandfathers returned to their countries of birth, even to visit. They had been driven abroad, escaped mass slaughter, and arrived alone on America’s shores. Once there, they cast away the old world, rendered themselves in this country’s fabled melting pot, and became American in ways that made return genuinely unthinkable. Theirs was a story of America, maybe even the story of America, a tale I would say practically screams The American Dream—if I were the sort of American who would say such a thing, at any volume.

But this country needs a new story. There is no melting pot anymore, if ever there truly was one; no set of behaviors, values, tastes, and experiences that unanimously defines its citizens, born or made. To be American, today’s immigrants do not have to change their names, or slap freedom isn’t free bumper stickers on their cars, or develop a taste for hot dogs and the Indy 500. And that’s good, but different. Yet even as the cost of becoming “one of us” has gone down, if only slightly, some immigrants now seem unwilling to pay it. I wanted to understand why. For some writers, reckoning with this phenomenon might lead to a kind of nebulously defined American “heartland.” I chose instead to go to Vietnam.

Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the creation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in September 1945, in a speech in Hanoi’s Ba Dinh Square, a few minutes’ walk from what is now the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum, where his embalmed body lies eerily in state.* Ho opened his address to the Vietnamese people by quoting the Declaration of Independence, in a bid for U.S. support that he did not receive. What followed was war with two colonial powers, one waxing and the other French. There was civil war and guerrilla war and proxy war and a war of occupation and a war with China. There was reeducation, mass flight, collectivization, the failure of collectivization, renovation, the turn to markets and the unleashing of mercantilist energy. Through it all, the Communists clung to power, state-owned businesses unwound, corruption held fast, and the country hurtled from poverty into the global “middle class.”

Over time, there has been a slow and fitful return of the exiles, the Viet Kieu: the “Vietnamese overseas.” There are an estimated 4.5 million people of Vietnamese descent currently living outside the country. This is not just a byproduct of the war with the United States. Vietnamese people have gone abroad in sizable numbers throughout the nation’s modern history. Ho famously lived in Paris before returning to Vietnam to help free his people. During the later stages of the Cold War, Vietnam was a Soviet satellite state, and many Vietnamese went to Soviet-bloc countries to study and to work as contract laborers. Others went to Cambodia, many relocated there by the French during colonial rule and some arriving when Vietnam invaded the country in 1978. Viet Kieu communities remain there, as well as in parts of Laos and Thailand.

There are more than two million Viet Kieu in the United States, and nearly all of them are there because Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon had containment on the brain. In the early years after the war, the Vietnamese government and Viet Kieu viewed each other with distrust and hostility. Return was not feasible. The mass flight from the country had been illegal, at least according to the Communist government. It was possible that returnees would be harassed or punished. For many Viet Kieu, those fears persisted even after it became clear that they would be safe. Eventually, the government accepted that it had to offer rights to diasporic Vietnamese, in order to tap into their wealth and skills. There were several milestones in this relationship, but perhaps the most important one came in 2004, when Vietnam’s Politburo issued Resolution 36, which recognized the Viet Kieu as a valued part of the greater Vietnamese nation. (It also stated that some Viet Kieu still “go against the common interests of the nation, trying to destroy the country.”)

Regulations governing visas, residency, passports, real-estate purchases, other investments, and even how much Viet Kieu are charged for entrance to tourist sites have all steadily eased. The Vietnamese government does not reliably track how many have returned either permanently or semi-permanently. There are still brutal extremes of inequality in Vietnam, and a corrupt and repressive government that is almost universally regarded as opaque, sclerotic, and inept. There are other, more subtle obstacles to return as well, such as unhealed emotional wounds suffered during the war and years of separation.

And yet American Viet Kieu do go back. They upend the classic path of migration from poor country to rich. They rewrite the American dream as my grandfathers’ generation lived it, as my parents learned it, and which I have come to regard with something bordering on regret. For the Viet Kieu, the pull factors, as they are called, are strong and emotionally rooted.

Source images: Bitexco Financial Tower, in Ho Chi Minh City © Kevin Miller/Alamy; vendors in Hoi An © John Milligan/Alamy; Tra On, in the Mekong Delta region © Robert Harding/Alamy; Mekong Delta © Jason Langley/Alamy

“All Vietnamese have to come back eventually,” Peter Cuong Franklin told me. He was draped across a tall bar chair on the second-floor balcony of his restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City. “Mother Vietnam keeps calling.”

It was early on a weekday evening at the end of the dry season. The waitstaff and cooks were setting up for dinner service, and Franklin wanted to sit outside and smoke while we talked.

His restaurant, Ănăn Saigon, was located in a five-story, wedding-cake-style house, half-hidden behind the stalls of the Ton That Dam market. (Ăn Ăn means “Eat! Eat!” in Vietnamese; the second-floor bar was called Nhâu Nhâu, or “Drink! Drink!”) The market was slowing down as night came on, and the karaoke machines were firing up. Fishmongers had stopped cutting fish and begun steaming piles of clams and cockles and selling beer served on ice. Women squatted by pyramids of brilliantly colored tropical fruit. Shirtless men made repairs on things, or lashed stuff tight for the evening, or napped. Old men stared into the distance. Nattily dressed youths zoomed by on scooters or toyed with their smartphones.

The market was an increasingly incongruous artifact in a city whose mania for progress had pushed much of this sort of commerce to its periphery or indoors. It was wedged into an urban canyon created by glass and steel towers. At one end loomed the long, slender dart of the Bitexco Financial Tower, home to the Saigon Skydeck, a glass-walled observatory and shrine to the megalopolitan sprawl.

Franklin is one of what’s known as the 1.5 generation of Viet Kieu, those who were born in Vietnam around the end of the war but left as babies or young children. They typically speak a rough but fluent Vietnamese and often cannot read or write in the language. The 1.5 generation sits between the first-generation Viet Kieu, who were born in Vietnam and went to the United States as adults, and the second generation, who were born and raised in the United States.

Franklin’s story of exodus began, as many Vietnamese emigration stories do, in April 1975, a few days before the end of the war. He was twelve years old, and he made his way south from Dalat, in the Central Highlands, to Saigon with his younger brother. They had a relative at Tan Son Nhut Air Base, which was blasted with North Vietnamese rockets the night they arrived. They managed to get on a Huey, then onto a waiting American aircraft carrier, and then to Guam. After a month, a U.S. Navy chaplain adopted them and took them to Chicago, where he was stationed. Franklin had left his mother behind in Dalat, and he did not see her again for twenty years. It had been his first trip to Saigon.

“We came only to leave,” he said, and shrugged.

Franklin, a wiry man in his mid-fifties, was dressed in a chef’s black T-shirt and jeans and a black denim apron. He had a certain impatient kind of cool, even as he gulped from a glass of water and sweated in the stifling heat. I caught a whiff of the previous night’s after-work drinks and that day’s prep work. His straight black hair seemed to spring from his head, bowing to gravity at the tips and arcing toward his narrow mouth. He pushed it from his eyes every few seconds to pull from a cigarette, chewing at the filter between drags. His face was rutted and wrinkled, and his eyes guarded until something struck him as funny, when he would break into a sardonic smile.

Franklin spent his first years in the United States on naval bases. “I went to seven different high schools. I learned to adapt,” he said. “I know more about America than Americans.”

His adoptive father, whom he calls his father, eventually left the service, and the family settled in western Connecticut. (Franklin’s biological parents never married, and he told me that his biological father had multiple wives. He has seen him two or three times since returning to Vietnam. He is close with his mother, who still lives in Dalat.) Franklin graduated from an all-male, Jesuit prep school, went to Yale, and then got into investment banking, at Morgan Stanley. He was a model minority, tracing the well-worn trajectory of America’s vaunted social mobility, until 1993, when his father died and his sense of who he was and where he belonged began to change.

“I was severed from America,” he said. “It was freedom for me, mentally. He was my connection to the United States.”

He crushed his cigarette in an ashtray and lit another.

“A lot of Vietnamese Americans struggle with identity. I’m not like that,” he said. “One of the keys in the diaspora is when you left. I was twelve. The ones who got out when they were twenty or thirty, they’re fucked-up mentally. It impacts their memories and connections to being Vietnamese. My thinking is very American. I have that optimism. You see it in how I deal with problems.”

In-between can be an excruciating place to find oneself. It is one of the reasons why previous generations of Americans gave themselves so completely to conventional U.S. culture. It is a straight and dependable path forward for an immigrant. That path is harder to follow now. Compared with white immigrants, Vietnamese Americans cannot as easily costume themselves in middle-American cultural finery and hope people play along. This makes them no less American. But there are pressures and there are choices.

And, Franklin added, punctuating his words with a theatrical pull from his cigarette, “I know who I am.”

A couple of nights later, Franklin invited me to join him for drinks after the restaurant closed. The place he chose, The Pub, was an American-style bar, lit like an interrogation cell, heavily refrigerated, and decorated with a few football posters. (Soccer! It wasn’t that American.) There was a long bar and a pool table patrolled by Vietnamese hostesses dressed in the short-skirted promotional outfits of various beers: Carlsberg, Tiger, Heineken. A foosball table, which I did not recall ever having seen before in Vietnam, stood by the entrance, and Bon Jovi and other American stadium-rock favorites blasted from the sound system at tinnitus-inducing levels. It was nearing midnight, and there were only a handful of customers, white expatriates and a few backpackers dipping their Teva-sandaled toes into the local sex trade.

The Pub was an odd spot for Franklin, who was so confident of his Vietnamese identity, to ask to meet. It was not tailored to the tastes of Vietnamese men, who like to drink while seated at tables or on the floor, not at bar stools. They like to have food with their booze, and prefer that everyone drink the same thing, at the same pace, like civilized people. That is how Vietnamese men get drunk. The Pub was a place for foreigners.

Franklin had come that evening with the sous-chef from his restaurant, Steven, a Korean-American guy from New Jersey. Several more Western men joined later. There was the owner of a local taco restaurant, who I think was from the United States, and a super skinny Irish dude who was reputed to be a lethal foosball player. The hostesses knew Franklin and his friends well. One of them rushed to bring him a bottle of whiskey from a case behind the bar. It had his name written on it in marker and was about a third empty. (Steven stored a bottle there as well.)

“These girls are all from the Mekong Delta,” Franklin said. One of the hostesses brought me a beer, and I asked her where she was from.

“Hanoi,” she replied. (The Mekong Delta is in the south; Hanoi is in the north.)

Franklin had apparently been drinking already, and he was flushed and acting a bit dramatic. He broke into a weepy Vietnamese song about Ca Mau, the southernmost province of Vietnam, which was also his nickname at the bar. The hostesses knew the tune and joined in.

“All Vietnamese songs are like that,” Franklin said at the end. “Someone looking back with longing.”

One of the hostesses called out a Vietnamese toast: “Một trầm phăn trăm!” (“One hundred percent!”) It meant you were supposed to drain your glass. You could also call ““Nầm mươi phần trăm,” or “Fifty percent,” but she did not do that. Franklin took his whiskey on the rocks. I was drinking beer from a bottle. The hostess had a 7 Up. We swigged awkwardly.

Then the foosball games began. It was tense and athletic and loud, the men versus the hostesses. This lasted about an hour. Franklin played, and I sat with Steven, who had a Connect 4 match going with one of the hostesses. Occasional celebratory outbursts, mostly from the women, erupted from the foosball table, along with a few arguments.

Franklin returned to our bar table. The hostesses had won, and he looked genuinely crestfallen. “In my blood, there is food and gambling,” he had told me at the restaurant.

Narratives of reverse migration from the United States are often freighted with ambivalence. It is no small step to leave behind the so-called nation of immigrants. In Vietnam, the government is ambivalent about the Viet Kieu, whom they need for money and expertise but whom they do not really trust and cannot truly control. Viet Kieu fear the government but profit from its greed and ineptitude. Vietnamese people who have never left accept Viet Kieu as their extended family but find their attitudes arrogant and their behavior un-Vietnamese. Viet Kieu ridicule other Vietnamese as backward but take offense if they are treated as outsiders. I met one man, a clinical psychologist, who had returned to Vietnam in 1998. He told me that his “life and orientation is utterly Vietnamese,” and that his “home is here,” but he also referred to Vietnamese people, whom he treated in his practice, as psychological “Smurfs.” You cannot break a nation and restore it simply with a visa waiver program and some cant about family ties.

Viet Kieu returnees once held an elevated position in Vietnamese society, earned through their exodus, their foreign passports, education, language skills, and bank accounts. But Vietnamese people can travel now; they can speak English, and go to Harvard; and they have much more money than they once did. Vietnam remains a poor country, but not uniformly so. Last year, the research firm Wealth-X forecast Vietnam as the fourth fastest-growing country in the world in the creation of “high net worth” people—a term describing those with assets between $1 million and $30 million. Vietnam’s increased wealth has changed the way Viet Kieu are perceived in the country. A 2015 article in Sojourn noted that many Viet Kieu felt their identity was no longer “a big deal” and “no longer special.”

I encountered this belief myself when I talked to Tra Tran, who until recently ran the Come Home Pho Good initiative for the international recruitment firm Robert Walters. Tran told me that the firm was “open to all candidates of Vietnamese origin,” but in practice that did not include first-generation returnees. “First-generation Viet Kieu often approach me, but we don’t have anything for them,” Tran said. Their language skills are usually outdated or poor, and they have a harder time adjusting than do younger people. “Clients don’t need them.”

It is not easy to lose status, and it is made no easier by the lessons Viet Kieu returning from the United States have learned as Americans, particularly if they did not find snap success when they returned. “The internalized myth of model-minority success for Asian Americans gets reproduced in Ho Chi Minh City,” wrote the sociologist Mytoan Nguyen-Akbar in her 2016 study “Finding the American Dream Abroad?” “Those who feel a sense of failure in Vietnam . . . experience a double sense of failure: not making it in either the United States or Vietnam.”

“Just because you’re Vietnamese doesn’t mean you will fit in here automatically,” Franklin said. “It is a transformation of the self. An older person comes back, and he can’t adapt very well. Young people can adapt, but they lack understanding of being Vietnamese.”

He saw himself as someone who had avoided these pitfalls. He had moved from the United States to Hong Kong in 2001 to work, and found that he liked it. “People looked like me. They were my size,” he said. At one point, he gave a friend traveling to Vietnam a hundred dollars to try to find his mother. The friend found her, still in Dalat, and Franklin rushed back to rekindle their relationship. In 2009, he decided to learn to cook professionally, at Le Cordon Bleu in Bangkok, later working in restaurants in Hong Kong and Chicago and then Hanoi. He opened Ănăn Saigon in 2017.

The restaurant was a success, and Franklin felt he had confronted his identity issues before returning to Vietnam. And yet here he was, in The Pub, a liminal zone between Vietnam and the United States, playing foosball like a frat boy. As the night wore on, he repeated something else I had heard him say before, emphasizing it with a weird tenacity.

“I know where I was born,” he said. “And I know where I’m going to die. I know the beginning and the end. It gives me flexibility.”

Le Viet Phu was working on his PhD in economics at Berkeley when he “lost his faith in humanity,” he said, by which I assume he meant the United States. This was in 2012, and he had been in the country for seven years. Two black teenagers attacked him on a public bus in Oakland, he said, and tried to take his laptop, which had a draft of his dissertation on it. “I told my friends what happened,” Phu told me. “And they said ‘black kids do this.’ ”

I talked about a lot of things with people who had returned to Vietnam, but in many ways what I really wanted to know was whether America had failed them. Other than Phu, they all seemed to reject this idea, either implicitly or explicitly. I struggled to understand their reasons. Phu had a patently racist reaction to his misfortune in the United States, but many Viet Kieu had themselves been traumatized by racism and xenophobia. They had complaints about life in the United States. And they left. Whatever it was that becoming American was supposed to do for newcomers, whatever it was supposed to give them, had not been enough.

Phu showed me around Fulbright University Vietnam, where he was a professor. The Fulbright campus took up two floors of a squat building in an office park, in an exurban district cut from what had recently been a greenbelt of rice paddies and mangrove trees.

The office park seemed either in its early stages of development or nearing collapse. The building was framed by a man-made lake on one side and a sweeping grid of mostly unused roads and sidewalks on the other.

There was a Panera-like coffee and sandwich shop and a Shabu Kichoo restaurant running some sort of buy-one-get-one-free promotion. The university resembled a community college in a medium-size city short on zoning regulations, or the headquarters of a software startup in the Rust Belt. There were classrooms crammed with bright young men and women squinting under fluorescent lights, generic offices, a central cubicle farm in gray and white, and a few clusters of laptop desks and overstuffed chairs.

Fulbright opened in 2016 as Vietnam’s first independent nonprofit university. Its American pedigree and political backing left it well positioned to succeed in a country with a voracious appetite for private education. Ho Chi Minh City was bursting with private universities, international primary and secondary schools, test-prep and language centers, and the consulting firms and “educational agents” (and private-equity funding) that kept the market bubbling.

Yet its progress had not been without friction. Former Nebraska governor and senator Bob Kerrey, a Vietnam veteran, was the first chairman of Fulbright’s board of trustees. Kerrey had been an early advocate for renewed relations with Vietnam, along with John Kerry and John McCain, who had also fought in the war. But Kerrey was a contentious choice; he had been part of a 1969 raid on the Vietcong in the Mekong Delta that killed at least twenty women, children, and elderly men. His appointment kicked off a wave of criticism in the Vietnamese press and on social media. Kerrey was slammed by Vietnamese citizens, as reported by Politico, as “a killer in cold blood of women and children” and “someone who committed a horrific, evil massacre against a previous generation.” He initially resisted calls to step down, but quietly relinquished his title in early 2017.

Fulbright was building a larger campus in another section of the outer city, in a different office park. The first phase of construction was expected to wrap up in 2022.

Phu and I went outside for a few moments and talked in the shade of the building. We didn’t last long before it grew too hot and we moved to the café.

Phu was a compact man with a tight smile and the slight remove of someone who is better educated and smarter than most people he meets but who does not always profit from it. He twisted a tissue in his hands as we talked. His years in the United States had not been easy, and he returned to Vietnam embittered about U.S. politics and culture. He blamed Barack Obama for many of America’s social problems, and he was disturbed by how the president had, in his view, divided the country along racial lines.

“I was a victim of his race policy,” he said.

Phu felt isolated from white Americans by discrimination, and angry at black Americans because he believed they had victimized him. (The bus incident was the second time he had been assaulted by people who were black.) He had no affinity for the Bay Area’s Viet Kieu. “These are the sons and daughters of boat people,” he said. “They have an unfair feeling toward the Vietnamese. We are Communists and they suffered. They are so cocky, so fancy in their behavior. It made it hard to integrate,” he said. “Maybe I should have lived in Colorado.”

Vietnam is one of a small group of nations whose people tend to hold positive views of Donald Trump. Trump’s 2017 state visit and his 2019 summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un in Hanoi were widely viewed as signs of respect, and while there was concern when he spiked the Trans-Pacific Partnership, it was counterbalanced by how “tough” he was perceived to be on China.

Vietnamese families spend more than $3 billion a year sending their children abroad for education, and much of that money ends up in U.S. institutions. Vietnam’s 24,000 students in the United States contribute an estimated $990 million to the economy, according to the most recent “Open Doors” report from the Institute of International Education. They make up the sixth-largest population of international students in the country, after Canadians. One Vietnamese family was even embroiled in the college admissions scandal of last year. The New York Post reported that a “tiger mom” from Vietnam had paid $1.5 million to an admissions firm called the Ivy Coach to help her daughter get into an elite American college.

The Vietnamese student population in the United States has continued to grow during the Trump presidency, as it has for more than a decade. But concerns about Trump-era racism and xenophobia may be causing students to rethink their plans. “For the first time ever, there are nearly half as many Vietnamese students in Canada as there are in the U.S.,” wrote Mark Ashwill, cofounder of an education consulting company in Vietnam, in a 2018 article in University World News. “Is it possible that ‘cold’ and ‘boring’ have been supplemented or supplanted in their minds with quality, tolerance, openness and safety?”

Trump’s impact is not limited to foreign students. Bill Dao is Vietnamese and lives in Seattle, working for Becamex IDC, a Vietnamese conglomerate that he told me was the largest developer of industrial parks in Asia. (Someone has to be, as my father would say.) Dao was a good friend from my time living in Vietnam. When I met him, he worked for the Canadian Consulate and went by the name Tung. “Call me Bill,” he said when we spoke on the phone, last April. “New country, new name.”

Dao organizes trade conferences in the United States to promote investment in export manufacturing in Vietnam. “Since Trump was elected, the government and the Department of Commerce—they are skeptical of me,” Dao said. “People don’t look at foreigners the same way as before. They think I am trying to take jobs out of the United States, but I say, ’No, I am creating jobs for the U.S.’ This is only for the ASEAN market. Since Trump took over, my job is tougher.”

I also spoke to Vy Pham Haq, a Vietnamese-American immigration attorney based in both San Diego and Ho Chi Minh City. Haq fled Vietnam with her family by boat when she was six, and she now helps Vietnamese people apply for visas to the United States. Her specialty is the EB-5 visa, which is for wealthy investors willing to commit large sums to U.S. enterprises. Once Stateside, she said, such investor-immigrants typically obtain a green card. “It is a huge change since Trump was elected,” Haq told me. “My normal cases are taking longer. Even those easy cases, which years ago they didn’t care about, are taking longer. They want more evidence. It’s a lot harder with Trump in office.”

In 2017, Trump threatened to deport approximately eight thousand Vietnamese immigrants, most of whom had criminal convictions in the United States. Such a move would be in violation of a bilateral agreement with Vietnam, signed in 2008, not to deport immigrants who had reached the country before 1995—that is, before the reestablishment of diplomatic relations. Trump’s actions seemed driven more by his general xenophobic antipathy than any dislike of Vietnamese Americans, though Vietnamese Americans might actively dislike Trump. In the 2016 election, just 17 percent of Vietnamese-American voters identified as Democrats, but 61 percent voted for Hillary Clinton, according to a post-election survey by AAPI Data. The Vietnamese government resisted any official change to the 2008 deal, and Trump has so far deported only a handful of pre-1995 arrivals. The dispute remains a source of tension between the two governments.

Despite these developments, the United States seems to have maintained its potent emotional pull for immigrants. Dao has Canadian citizenship, but he recently received his green card in the United States, and that was where he planned to make a life. He would not be returning to Vietnam. “I feel less corrupted here,” he said. “I have more freedom.”

Haq told me that even under Trump she had seen an increase in demand for visas. “My clients, even the rich ones, the millionaires, they want to go to the States,” she said. “I ask them: ‘You are so rich, why would you want to go?’ It is for their kids, for that freedom and choice,” she said. “It is because of the dream.”

Phu, for his part, seemed to have few regrets about coming home. “I used to think of the government only as repressive and authoritarian,” he told me, in the café outside the Fulbright campus. “The top level of the Party is still shitty, of course. But it’s not like China with its conflict and clash of society between rich and poor, urban and rural.”

Phu spoke with pride of the first cohort that he was stewarding through the university. “I am really impressed by their level of understanding,” he said. “I wish I had known about this before. I would have returned home earlier.”

The war was a long time ago. Nineteen seventy-five was a long time ago. The camps in Hong Kong and Malaysia and the Philippines were emptied out a long time ago. Saigon was de-urbanized, “Vietnamized,” reurbanized, and turned into Ho Chi Minh City a long time ago. Dổi mới, the economic reform program that ended collectivization and guided Vietnam toward a market economy with a chicken in every pot and a Louis Vuitton store in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, was a long time ago. Relations were normalized, most-favored-nation status obtained, and the World Trade Organization joined a long time ago. Bill Clinton and George W. Bush went to Vietnam, without being drafted; Barack Obama did, too. Trump, despite his bone spurs, has been twice.

And now, among those who have returned are those who had previously never been. Anh-Thu Nguyen was born in the United States, in 1985, and was raised in a suburb of San Francisco. When I met her at a restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City, she was dressed in black silk trousers and a black blouse with a white flared collar. Her hair reached down to her left shoulder and was shaved close on the right side of her head. She had a kind of eager self-consciousness that she carried in her eyes, which were appraising and a little anxious.

The restaurant she had chosen had a global-nomad-meets-postcolonial vibe: teak tables and chopsticks with mother-of-pearl inlay. The fare was delicious, “authentic” (the restaurant’s term) Vietnamese food. The clientele appeared to be upwardly mobile Vietnamese, some of whom were probably Viet Kieu, and white expats dressed rather more French than American. (Franklin’s cuisine was closer to fusion. His menu included “banh xeo tacos” and “deconstructed pho” with a “broth sphere,” Wagyu beef, and black truffles.)

Because she was born in the United States, Nguyen did not have a Vietnam story: her parents did. Her father, a soldier in the southern army, met her mother in Guam just after the fall of Saigon, and then again at Fort Chaffee, in western Arkansas, after they had both made it to the United States. A white Catholic family in St. Louis sponsored her dad. Her mom went to California. They wrote letters and made collect calls. Eventually, they reunited on the West Coast.

“I’m queer-identifying,” Nguyen told me. “I always had to keep that separate from the Vietnamese-American community.”

“That’s an odd thing to say about San Francisco,” I joked. She laughed.

“I was very out, but there was gay time and Vietnamese time,” she explained. “The idea of being queer was a Western thing. Vietnamese spaces were straight spaces. Queer spaces were queer spaces. In Vietnam, there are people who are fully Vietnamese and fully queer. I can address both aspects of myself here.”

Nguyen made her first trip to Vietnam in 2006, when she was twenty-one, on a grant to study LGBTQ issues. Two years later, she volunteered as an English teacher in Tra Vinh, a city in the Mekong Delta. I’d passed through Tra Vinh years ago on a couple of occasions, during Tet, the Lunar New Year. I had friends whose families were from the delta, and I had gone home with them to visit. Tra Vinh was remote and dusty, the kind of town to speed through. It was a jarring experience for Nguyen.

“My Vietnamese kinda sucked. It still does,” she said. “There was no culture of diversity. They make fun of your accent. I was relentlessly mocked.”

She moved to Ho Chi Minh City in 2011 and immersed herself in the queer scene. She volunteered at LGBTQ events, and helped organize some. In 2018, two of the female contestants on Vietnam’s version of The Bachelor came out on air, rejecting the male bachelor in favor of each other. Nguyen had worked part-time as a story producer on the show, she told me, helping ensure that the press around the show never got too “salacious.”

She said her family in Vietnam was “tolerant but not embracing” of her identity. “They are more open than people in the West would think. In Buddhism it isn’t a sin to be queer. It’s more about filial piety. Collectivism. You’re supposed to marry and have children, and the notion of having your heart’s desire isn’t as strong here. The main thing is not to lose face.”

Not all of Nguyen’s family got out in 1975. She told me about a Tet celebration she went to in Vietnam and how being able to celebrate her culture in the place her parents had fled made her realize “what they lost out on by coming to America.” Nguyen’s parents had achieved what she, in a later email exchange, called “the middle-class American dream (life in the suburbs, small business owners, their kids went to elite colleges).” But it had not been as easy for everyone. And some of those in her family who had stayed in Vietnam eventually grew wealthier than those who made it to the United States.

Remittances have always played an important role in Vietnam’s economy. For years, Vietnamese families in the United States, many of them poor, sent money “home” through informal networks of brokers, or brought it themselves when they visited. The money helped pull Vietnam through the harshest years of postwar poverty and government control of the economy. Remittances were about more than charity or family ties. They were a marker of connection, a symbol and signpost that the bonds between the diaspora and those back home remained strong.

In Currencies of Imagination: Channeling Money and Chasing Mobility in Vietnam, the anthropology professor Ivan Small studied trends in remittances. His research showed that regular remittances typically stopped once a member of the diaspora traveled to Vietnam for the first time and saw how conditions had improved. Yet the cash still flows: $16 billion in 2018, according to the World Bank, nearly 7 percent of Vietnam’s GDP, putting it in the top ten worldwide for remittance receipts. But the money is being put to a different purpose. In 2016, 71 percent of overseas remittances were used to set up or expand a business, according to VnExpress International. Ho Chi Minh City received the most that year, $4.4 billion, but only 6 percent was used for “financial support for families or friends,” which, the article noted, “used to be the key purpose of remittances.” So the bonds have held, but they are now used less for support, with its connotations of love and dependence, and more for investment, which is about overlapping self-interest.

Modern migration does not lend itself to easy calculations of identity and obligation. The barriers dividing people of different nationalities have grown more permeable, and perhaps more meaningful as a result. Nguyen’s understanding of Vietnamese culture was rooted in a connection that spanned history, family, and a specific way of thinking about people in relation to one another. But what she wanted from Vietnam was also undeniably American.

The traditional narrative of America is of a country that took immigrants in and sheltered them, but at the cost of who they once were. Embedded in that narrative is a question, one that immigrants to our country have always faced, but perhaps now more than ever: Are you American enough? It is an offensive question, and menacing. It conjures a world in which real Americans jostle false ones, and full Americans outrank provisional ones. In that world, the United States is a nation bounded by racial and ethnic identity, rather than a country conceived as a system of absorption. But Nguyen, it seemed to me, turned this question on its head. She felt that by leaving America she had found a deeper understanding of what made her parents, and herself, American. This did not strike me as a rejection of the country, but a new and hopeful way to accept it, on better, less transactional terms.

Nguyen said she had no plans to return to the United States, but she would not rule it out either. “It’s very fluid,” she said. “I never really cut the cord to the U.S.” She did not have a Vietnamese passport and had no plans to get one, although she would not have to give up her U.S. citizenship to do so.

“I’ve found it to be really beautiful in Vietnam,” Nguyen said. “I had to go all this way to understand my parents’ culture and their lives as refugees. The racism and the xenophobia they experienced. All they gave up. I can relate to it now.”