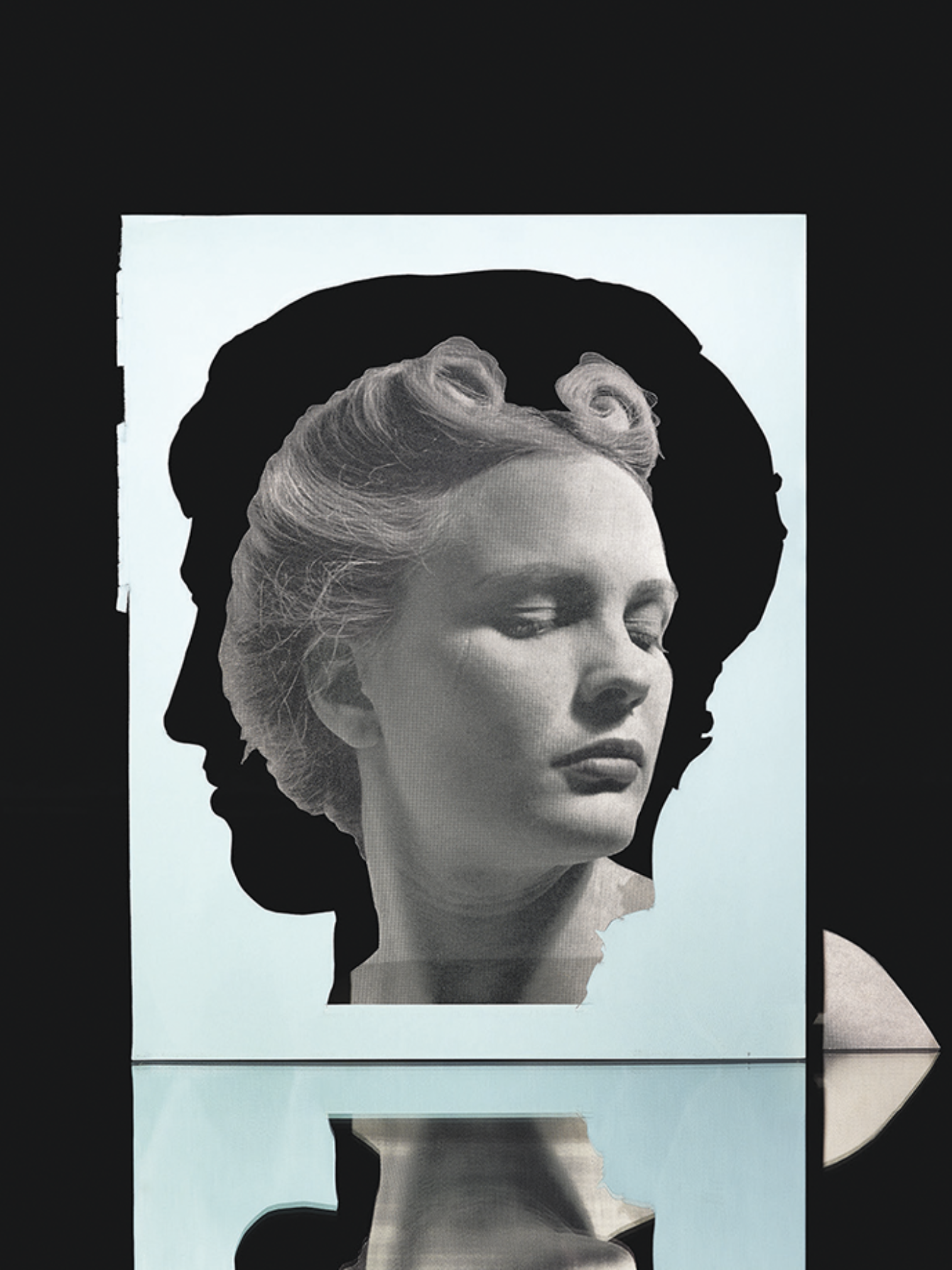

“Screen (0X5A8295),” by Paul Mpagi Sepuya, whose book Paul Mpagi Sepuya was published in April by Aperture © The artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles

My friend Jenny Boylan and I are both incorrigible dinner-party raconteurs who love to one-up each other with stories about our misspent youths and eccentric families. Since we’re both writers, the best of these tales run the risk of theft, which is why often, as soon as the speaker’s voice falls, the listener will serve notice: You have one year to use that, we warn, after which the story becomes fair game. Of course, these aren’t so much “stories” in the literary sense as alcohol-fueled anecdotes, and often it isn’t even the whole tale we covet, just its setup, perhaps, or a particularly vivid image. Jenny once made the mistake of telling me about a relative of hers whose lengthy visits were always preceded, sometimes weeks before, by the arrival of his enormous trunk; the idea so tickled my fancy that I used it as the basis for a screenplay that became the movie Keeping Mum. (And no, I didn’t share the money.) Implicit in our agreement is a shared belief that nobody really “owns” the raw material from which fiction is made. No doubt the fact that we’re such good friends also plays a role. We share some of our best material because we know we can trust each other with intimate knowledge. When Jenny decided to transition, I was one of the first people she confided in, and I was with her when she underwent gender-confirmation surgery. As a result, for the past decade or so, I’ve had a better window than most cis men through which to view the lives of trans women. Still, I’ve never put a trans character in one of my fictions. I take that to mean that I’ve voluntarily placed a limit on both what I’m willing to borrow and what I’m capable of imagining. I wouldn’t argue that I have no right to do either, only that I’m constrained by friendship.

But such is not always the case, even when love is involved. My mother would’ve hated every word of my memoir, Elsewhere. Though I never promised not to write about her life—I had already done so obliquely in my early novels—she would have seen Elsewhere as a terrible betrayal. That I waited until she died to write it didn’t really matter, because other people who loved her were still alive, and I told those people a secret that she’d guarded at great cost her entire life: that she suffered from crippling anxiety, which manifested as paralyzing panic attacks that got worse over time because they went untreated.

My writing Elsewhere meant that many of her friends and relatives wouldn’t be able to remember her as she had wanted them to. Who would do such a thing, you ask? Well, writers do, to some degree, pretty much every time they put pen to paper. We are, like other artists—painters, photographers, filmmakers, musicians—people who make use of whatever materials are at hand, much as carpenters use nails and wood. Without these materials, we’re out of business. Nothing gets made. Flannery O’Connor argued that writers’ materials are humble—whatever exists in the world, whatever can be apprehended by the senses—that is, rocks and trees and lakes, and, yes, people. It’s probably worth saying again: writers use people. That’s inevitable and inescapable. What matters most is how we use them and for what purpose.

Take, for instance, the octogenarian nun who’s the protagonist of my story “The Whore’s Child,” which was published in this magazine in 1998. In it, Sister Ursula tells her life story to the other students in a creative-writing workshop over the course of a semester: how as a child she, the daughter of a prostitute, was taken to a convent and abandoned there; how she was made fun of relentlessly, not just by the other children but also by the nuns; how she patiently waited to be rescued by her beloved father, who had solemnly promised to fetch her as soon as he could find work. It’s a cruel tale, and it’s made that much crueler by the fact that in Sister Ursula’s final workshop another student intuits a terrible truth that the old nun herself had never suspected: that her father, the man she had counted on to rescue her, was her mother’s pimp, his looking for work a lie. All Sister Ursula’s life she had blamed her mother for things that were someone else’s fault. To the father she worshipped, she had always been expendable.

When I toured with my first story collection, also titled The Whore’s Child, I was both surprised and thrilled to learn how forcefully the story had landed. Sister Ursula had broken readers’ hearts, much as she’d broken mine. Not so the story’s other main character, the middle-aged professor who teaches that creative-writing course, a novelist whose career has stalled and whose marriage is crumbling as the result of an extramarital affair. Because I, too, was a middle-aged novelist who taught creative writing, it didn’t surprise me when readers wanted to know if I myself was the writer in the story. Was I getting divorced? Did I think my own writing career had stalled? To such queries I gave a glib reply that was at least half serious. Why, I asked, didn’t they want to know if I was the nun? Because it was Sister Ursula of whom I was proudest and to whom I felt the deepest psychic connection, though I’d never been and never would be an eighty-year-old Belgian nun. And yet I’d told her story to readers, many of whom were clearly convinced of her reality. Okay, they weren’t octogenarian Belgian nuns either, at least not to my knowledge, which meant that if I got things wrong about her life in the convent, I was pretty safe. Sister Ursula was real only in the peculiar way that vividly drawn fictional characters are. Readers understand them to be figments of their authors’ imaginations, yet somehow care about what happens to them as if they were friends or relatives. Sister Ursula limps through the first installment of her story on bloody feet, having been given shoes that were two sizes too small when she entered the convent, and her suffering hurt both her creator (me) and readers, most of whom, one assumes, have had little or no firsthand experience of wearing shoes that are too small or of being abandoned in a Belgian convent. Despite Sister Ursula’s stipulated unreality, we still share her imagined suffering. How does that work, exactly? And conversely, why doesn’t an abundance of shared experience guarantee empathy? Indeed, too much shared experience can at times impede emotional connection. Imagine, for instance, the reception “The Whore’s Child” would have had if only elderly cloistered Belgian nuns had read it. Would Sister Ursula feel real to them? Or would they laugh her out of the convent, and me along with her? Because, come on. Who is this middle-aged American writer who clearly never spent a minute in a convent, or in a nun’s habit, or probably even in Belgium? What gives him the right to intrude so arrogantly into our lives? Why doesn’t he understand that Sister Ursula’s story simply isn’t his to tell?

“Portrait I,” by Matt Lipps © The artist. Courtesy Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Beverly Hills, California; and Josh Lilley Gallery, London

The time-honored answer to this what-gives-you-the-right question is: creative imagination, which for the writer is a muscular species of empathy. Okay, I’m not you, the logic goes, but if I take the time to observe you carefully, if I study how you navigate the world, if I listen to you when you speak, then in time I can begin to imagine what it feels like to be you. Obviously, the important word here is “begin,” because employing creative imagination isn’t as simple as asserting your right—obligation?—to let your imagination range freely. The further a story strays from your first- and secondhand experience (this happened to me or I witnessed this happening to somebody I know), the greater your need to narrow the ignorance gap, to make sure the details are as close to right as you can get them. Your need for a tutorial, though, should probably serve as a caution: presumably there are other writers out there for whom that gap is narrower, their own personal experience having dovetailed with your shared subject matter.

The good news is that in addition to research there are techniques at a writer’s disposal that will mitigate this problem of authenticity. For instance, instead of selecting a point of view that looks through your character’s eyes as the story unfolds, you can give yourself some distance by choosing an external vantage point from which to see her. Or you can use an intermediary—someone more like yourself—to interpret the story’s main character, the way Conrad used Charles Marlow, Fitzgerald used Nick Carraway, and Roth used Nathan Zuckerman. Should the day ever come when I want to write a story with a trans protagonist, I would surely employ such a device. My friendship with Jenny wouldn’t allow me to assume that I could convincingly walk in her shoes (or even, for that matter, stand up in them).

But if there’s a serious gap between your personal experience and that of your story’s protagonist—say, in age, gender, race, class, nationality, or occupation—how can you gauge your chances of bridging it successfully? Do you even know enough to embark? How much additional research will you need to do? Will strategies like the ones noted above, together with your experience writing other stories, save you? It’s impossible to know for certain, but again consider my Sister Ursula. Readers probably won’t be shocked to learn that she was based on a real nun who took a workshop I taught back in the Eighties. Like my imagined Sister Ursula, she belonged to a dying order of nuns that the local Catholic diocese was warehousing in a ramshackle old house in a sketchy part of town. A big, strong woman, she was despite her advanced years the youngest of the ancient nuns who lived there, and it was her job to take care of those who were in ill health. And like Sister Ursula, she made no secret of the fact that she hated her life, past and present. She’d joined an order she despised only after it became clear that life was offering her no other choice. Was she ever given a pair of too-small shoes and forced to wear them? Did she bleed into those shoes as Sister Ursula did? Did she still limp in old age? Did she imagine burning that hated convent to the ground? I no longer remember which details were appropriated and which were invented. (Writers are free to forget what no longer matters, and they generally do. After a story of mine is published, I could be interrogated with rubber hoses about what I knew and when I knew it, but much of what was of paramount importance yesterday is blessedly gone today.) All I can say with confidence is that these cruel shoes were not stolen from Pee-wee Herman.

My point is that despite how different Sister Ursula was from me, I didn’t have to make up all the story’s narrative details. I’d had the opportunity to study the real woman my character was based on. I’d read her account carefully, and after each installment, she and I met to discuss both the text and what other students had said about it in class. Just as the narrator does in my story, I remember telling her that, in a fiction-writing class, it was okay to make things up—even to (gasp!) lie, if the lie served a greater truth—and I noted the poor woman’s reluctance to accept my advice. During that semester, I watched how she navigated the world, how dutifully she read the other students’ stories, how troubled and mystified she became when she read them. Even her curious and sometimes revealing syntax ended up in my story. In other words, what I observed about the real woman closed the gap between me and my fictional nun. Sister Ursula was eighty and I forty-five. She was a nun and I was an English professor. She European, I American; she poor, I comfortably middle class. Those differences didn’t matter as much. So . . . home free, right? Not exactly.

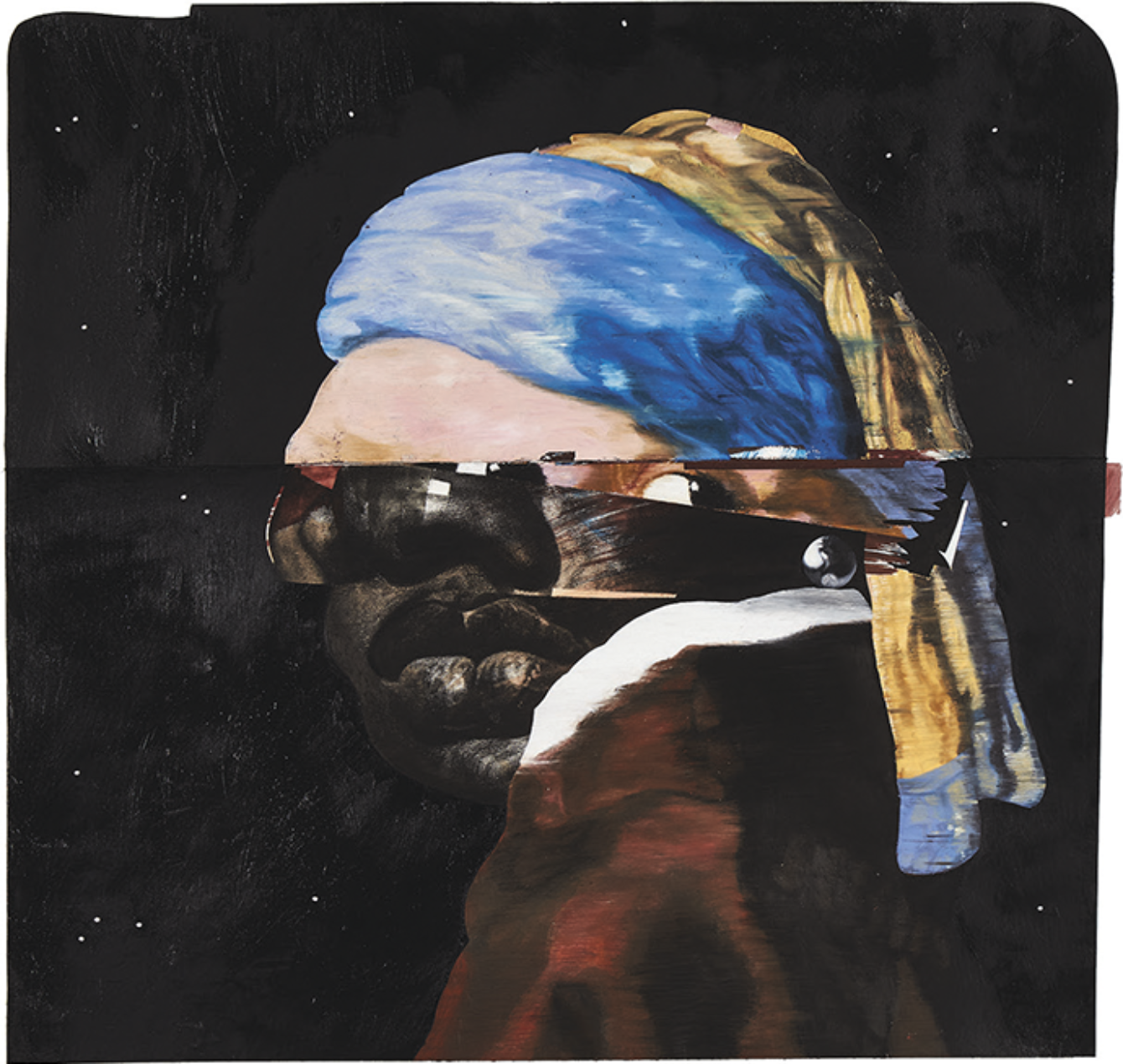

Erica with the Pearl Earring, by Nathaniel Mary Quinn © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

What I’ve been discussing is the how of writing a story that requires some degree of transcendence: how you go about bridging the gap between what you know and what you don’t and sometimes can’t. But in the end, it’s the why that matters most. Why tell the story in the first place? Back when the nun was in my writing class, I had no idea I would ever use her. What I did know, as writers often do, was that she piqued my interest. Like most authors, I unconsciously classify everything into two categories: what might one day be of use, and everything else. It’s an embarrassing habit, selfish in the extreme, but it’s also a kind of triage, necessary because you can’t pay equal attention to everything and be an artist. You learn, over time, to identify not so much what’s important as what’s important to you. What’s likely to bear fruit and what isn’t. It would be a good decade after I taught that creative-writing class before I would write the fictional one, a decade before the elderly nun I studied so closely without knowing why would limp from the back of my brain to the front and explain exactly what she meant to me.

But why did she do that? Why did I write her story and not some other? Because I remembered so much about her? Because what I’d learned through careful observation gave me the confidence necessary to begin? There’s probably some truth to that. Who doesn’t want to feel confident, especially at the beginning of a difficult endeavor? But it’s also true that writers—at least good ones—are more attracted to questions than to answers. If knowledge were all it took to write a good story, all artistic dilemmas would be resolved by further research; imagination wouldn’t factor in at all. What ultimately persuades the writer to embark upon a story is not confidence in his knowledge. Rather, he senses a powerful bond between himself and the person (or people) he’s writing about, a bond that makes the hazardous journey worthwhile.

When I ask why the old nun migrated from the back of my brain to the front, what I’m really asking is: Why was she important enough to remember when ninety percent of my firsthand experience of this precious life gets consigned to memory’s trash heap without much thought? Different though my character and I might be, this old woman’s story somehow intersected with mine. Was it that she spent so much of her life waiting for her father to come back, as I did after my own parents separated? Was it because she’d been mocked by other kids, as I had been (although no more than anyone else who’s survived eighth grade)? Was it because of the lifelong, love-hate relationship with Catholicism that neither of us could purge? Was it our mutual acknowledgment of the sad truth that cruelty exists because it’s pleasurable and that the very societal structures that should deter cruelty too often actually encourage it? Or did I go to the trouble of telling Sister Ursula’s story because I suspected I might come to love her? Because I thought readers might, too? Because her story might both entertain and instruct them? Make them feel less alone in the world than Sister Ursula herself did?

Readers might also ask what responsibility I felt to the woman who inspired Sister Ursula. Did I ask permission to use her story? No, I didn’t. For one thing, I’d moved fifteen hundred miles away, and I had no reason to believe she was still alive, but honestly it wouldn’t have mattered. The real nun, whom I remember with great affection, inspired but was not Sister Ursula. Okay, I’ll say it again. Writers use people.

We tell stories because we must. And the source of that must isn’t talent or knowledge or the authenticity that derives from research and lived experience. It’s mystery. What we don’t understand is what beckons to us. When I began writing Elsewhere, everything felt cloaked, especially the book’s strange urgency. I was deep in a new novel and having an absolute blast when I first became aware of Elsewhere’s gravitational pull, and I wanted nothing more than to ignore it. Why in the world should I put aside a book that was so much fun to write for another that promised little but heartache? The story’s imperative seemed to hint at some unfinished business between my mother and me, but how could that be the case? Hers had been a difficult life, and she was finally at rest. Why disturb it? I figured the book would be about how different our temperaments had been and how that had resulted in a grinding, decades-long contest of wills. She believed that many of the crushing anxieties she was prey to could have been alleviated if only I’d been willing to take her side in matters both large and small, to assure her that she was right, even, especially, when I knew she wasn’t. Why couldn’t I just pretend? Was that so much to ask? Why were we so often, so intractably, at odds? She knew we loved each other. What was she missing? But here’s the thing: instead of being a book about how different my mother and I were, Elsewhere turned out to be about how frighteningly similar we’d always been. The tractor beam of must that demanded I set aside my novel had nothing to do with what I understood and everything to do with what I’d stubbornly refused to grasp. This was the unfinished business I’d sensed but couldn’t articulate. In the end, a writer’s sense of must is a moral imperative, urging us to do this, not that. When we ignore it, our core mission is compromised. Our inability to explain it, even to ourselves, doesn’t diminish its power.

The primary obstacle to imagination isn’t lack of knowledge or lived experience. More often, it’s simply our need to get over ourselves. I came to storytelling late, and like many writers, painters, musicians, and other artists, I fell in love with the process long before I was any good at it. As an English major in college, I’d begun to understand why I’d always loved to read. Getting lost in a good story is an antidote to self-consciousness. But writing stories, it turned out, was even more rewarding. I’d always wanted to be a better person than I knew myself to be, and here was a pursuit that might actually help me achieve this goal. Deciding to become a writer had little to do with whether I might one day exhibit any talent. The activity was its own reward. I no longer felt quite so trapped. Yes, I’m me, I remember thinking. But for a time, I can also be you.

A Lawn Being Mowed (after David Hockney’s A Lawn Being Sprinkled, 1967), by Ramiro Gomez © The artist. Courtesy Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles

Earlier this year, when I mentioned to my elder daughter Emily, a bookseller, that I meant to write an essay defending the creative imagination and its moral urgency, she cringed, then posed an interesting hypothetical. What if the same mysterious force that made me set aside my novel for a memoir showed up again with an even more suspect project? Suppose I felt a strong imperative to write a novel about what it feels like to be a black man in America. Oh, come on, you say? Why would a white writer suddenly be visited by this particular sense of must? A fair question—except, well, it happens.

Consider John Howard Griffin, a writer who back in the Fifties darkened his skin in order to, in his own words, “become a negro.” The book he wrote about his experience traveling through the Jim Crow South was the huge bestseller Black Like Me, and despite the book’s extraordinary sales, there’s little evidence of opportunism in its writing or publication (both Griffin and his publisher envisioned a small, mostly scholarly readership). Apparently, the author just needed to know, firsthand, what it felt like to navigate the South as a black man. It could be argued that even with the best of intentions, he was still the wrong person to tell that particular story. But it could also be argued, given the historical context, that the wrong man was actually the right one. After all, black authors had been writing about the corrosive effects of racism for decades, and white readers had turned a deaf ear until one of “their own” chimed in. What Griffin did not do, however, is as interesting as what he did. Despite being a fiction writer, he didn’t write a novel. Rather, Black Like Me was a kind of literary hybrid, a “non-fiction novel” that predated Capote and Mailer. Griffin’s decision not to fictionalize his experience suggests he believed that being treated like a black man didn’t mean he could imagine what it would have been like to be born black and to live as a black man over a lifetime. After the publication of Black Like Me, he became friends with Martin Luther King Jr., Dick Gregory, and other prominent members of the civil-rights movement, but as time passed, Griffin grew increasingly uncomfortable talking about his famous book. There were other, more authentic voices, he decided, and they deserved the microphone more than he did.

But none of this negates the moral imperative Griffin must have felt to undertake such a radical experiment. Which raises an obvious question: What is a writer to do with that powerful feeling of must when the project it urges will strike others not as a moral imperative but rather as immoral opportunism? Because even if we acknowledge the power of the creative imagination, only a fool would ignore its hazards. My daughter reminded me that nobody ever gets everything right, and when it comes time for me to turn in my novel about what it feels like to be a black man in America, the manuscript will likely be read only by white folks. Roughly 80 percent of the people in publishing in this country are white. My editor will likely be white, and so will my copy editor. The sales, marketing, and publicity teams will be white, as will the reps who pitch my novel to bookstore owners, most of whom will be white, too. Which means it’s pretty unlikely that the mistakes I was hoping to avoid will be caught and corrected before the book goes to press. When I go out in public and give readers a wide, confident smile (one imagines Al Jolson seeing The Jazz Singer on the big screen and thinking, Nailed it!), no one will be smiling back. How will I respond when I’m told by people who know better that I didn’t, in fact, nail it? Will I be sore, having tried my best? Ashamed? (What on earth was I thinking?) Resentful that so few people understand how hard it is to write even a deeply flawed book? But ultimately, it’s not about my embarrassment. It’s about my doing a disservice to people who deserve better.

And what if, on the basis of my track record as a best-selling author, my publisher has advanced me a large sum to write this novel that turns out, despite my best efforts, to be full of inaccuracies? Doesn’t the money given to me diminish the opportunity for a black author who’s trying to sell his debut novel on a similar subject? How would I feel about being complicit in the silencing of that other voice? (Not great.) Doesn’t this in fact happen all too often? (No doubt in my mind.) Sure, we can argue that the ranks of authors today are more diverse than ever before, and that new voices are finding more and more success, but until the publishing industry itself becomes more diverse, can we really pretend the playing field is level? (We cannot.) And have I really stopped to consider (did Al Jolson?) how underrepresented communities are harmed by inauthentic representations like mine? (Ouch. Apparently not.)

“Constellations (XIX), Haunted Back Room, Memphis,” by Tommy Kha © The artist

When writers like me (older, white, male), who were taught that literary imagination was our stock-in-trade, leap to its defense, we don’t always realize what those justifications sound like to writers who are emerging into a very different publishing reality. When I broke in, there were more publishers to submit books to, and that competition led to larger advances. Back then, there was no Big Tech devaluing print books, not to mention no digital piracy. Nor was the internet chipping away at our attention spans with clickbait. Newspapers were still healthy enough to have book review sections. Authors of important, serious works understood that while they probably weren’t going to make fortunes, at least they had real careers, as did long-form journalists. Even younger writers got book tours, not because tours resulted in huge sales but because publishers were playing a longer game. Introducing and growing new talent was crucial to their own futures. And only a few publishers were owned by conglomerates that also sold televisions and cars and refrigerators (and expected books to yield similar profit margins).

Considering all this, can today’s emerging writers be blamed for concluding that they’re late to the party, that those of us who got here first have grazed the buffet, drunk all the champagne, and then ensconced ourselves in the comfortable chairs from which we can’t seem to stop banging on about the creative imagination and how all writers should be unfettered in its use? To them it must seem as though our real goal is to extend the many privileges we’ve gotten used to and now regard as our due. What choice do they have but to call us out, to turn the discussion to ownership, to argue not just that certain stories, but also the very materials out of which stories are made, belong to “people like me,” not “people like you.” Okay, I get that and I sympathize, but it’s also worth pointing out that ownership shifts the discussion from art to commerce, and these have always been at odds. Indeed, we seldom get really angry until money enters the equation. Yes, cultural appropriation is a serious issue, but books that garner ten-thousand-dollar advances and have initial print runs of eight thousand copies rarely spark serious outrage, even when they’re thoroughly botched jobs. The heated debate over the literary merits of American Dirt, a novel by a white woman about a Mexican bookseller fleeing a cartel, was no doubt a necessary one for the industry, but it was the book’s seven-figure advance and aggressive marketing campaign that caused battle lines to be drawn and invective hurled.

Lost in the tumult, I think, is how much time we spend documenting the literary imagination’s limitations when we might be extolling its triumphs. Books are flawed because their authors are. Yes, writers are beckoned by mystery and the need to understand, but also by money and fame. Shoddy work often pays better than genuine craftsmanship, arrogance better than humility, speed better than accuracy. It may be true that even when we make good-faith efforts to imagine what it feels like to be people very different from ourselves, we still fail far more often than we succeed. So what’s more important? Our numerous failures, or those rarer occasions when we beat the odds and somehow manage to get it right? Because when we do, the results can be truly glorious, and then identity politics fall away. Take Rebecca Makkai’s novel The Great Believers. Was that story about a generation of gay men lost to the AIDS epidemic really a straight woman’s to tell? How dare she? But seriously, who, having read the novel, would make that case? (Fair warning: if you do, don’t make it around me.) Don’t we want to hold up books that represent triumphs of the imagination and say that this, right here, is what we’re after? What’s more important for young writers to learn? That imagination has its limits? Or that its judicious use, and the courage needed to employ it, can make us better artists (and, yes, better people)? If I turn away from a story, should it be because someone else has told me it’s taboo, or because after my first draft I’ve reluctantly concluded that I’m not up to this particular task? There’s no reason I shouldn’t reserve the right to put a trans character in a story in the future, provided I acknowledge the moral responsibility that would trail in its wake. I would have to examine my motives, because in addition to (hopefully) making art, I would also (hopefully) be making money. I’d have to be willing to admit defeat and pull the plug should it become clear that the book I was writing was misbegotten, even if that realization came after years of hard work. I would owe my friend Jenny and all trans people that much.

I know—of course I do—that I can’t really be a black man any more than I can really be a nun. But why constrain the imagination, the very thing that helps us get over ourselves? Are artists really supposed to stay in their lanes? Those who argue that lived experience is the only legitimate source of authenticity, the only valid test of ownership, may provide a necessary corrective to arrogance and opportunism, but such proscription inevitably leads to timidity, and great art has always demanded courage. Surely we can agree on this much. Okay, granted, it’s not possible to be somebody else. We’re stuck with who we are. But this only means that when we pretend otherwise, both as readers and writers, we’re playing a very important, very serious game. We can’t be somebody else, but we have to try.