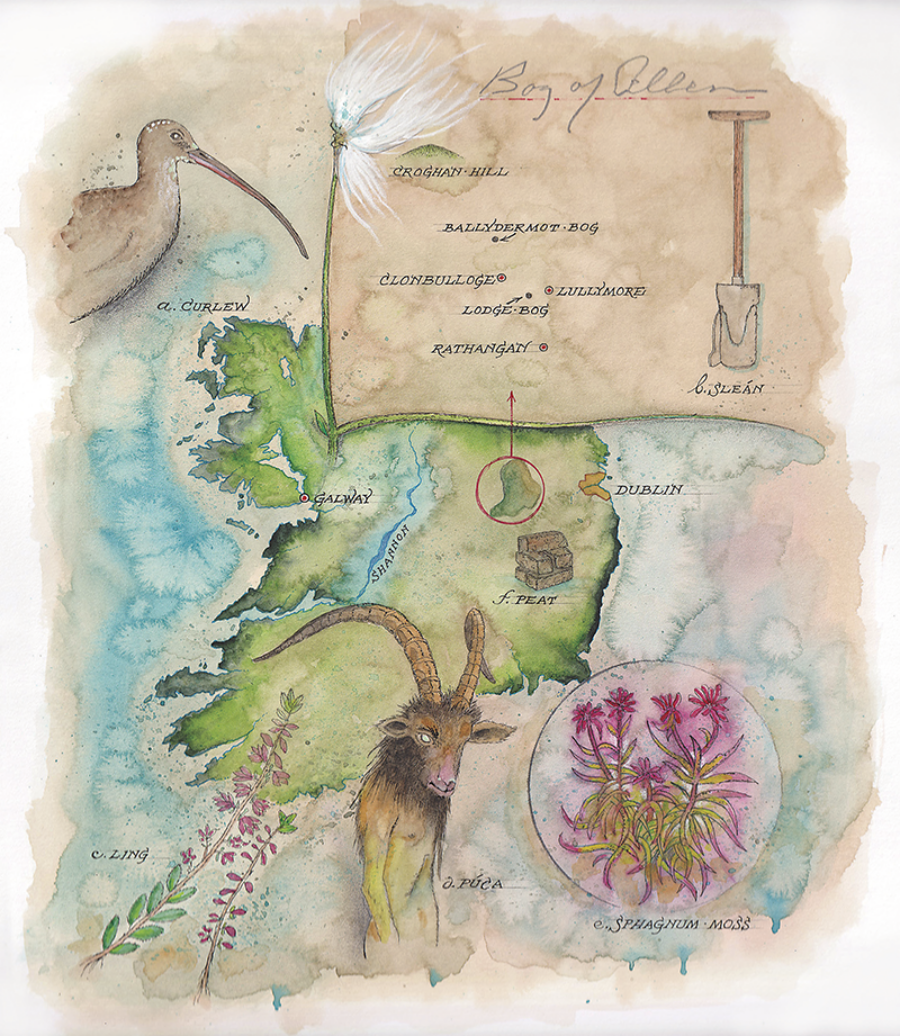

Map by Mike Reagan

The sky above Lodge Bog was a tarnished silver and four crows tumbled across it like blown cinders. It was a scoured, shelterless place, a realm of few verticals and uncertain horizons, the kind of environment humankind has tended to avoid. And yet, the bog was flourishing, abounding with life. To stand there felt like standing on the back of some vast recumbent mammal.

Lodge Bog is part of the Bog of Allen, a 960-square-kilometer swath of ancient peatland in the Irish Midlands. A thousand years ago, Lodge Bog was a lake. Over the centuries, that lake became shallower as it accumulated silt from incoming watercourses. Vegetation encroached from its banks, replacing open water with reeds and lilies. As these plants died and sank, the water grew shallower still, swampier, until a person could, with care, wade across it. A few hundred years more and the swamp had transformed into a fen, solider underfoot, dominated by rushes, grasses, and mosses. Year by year, these plants also died, forming peat—a wet, fibrous, brown-black mass—until the surface of the fen rose in a dome above the level of the surrounding land. A raised bog had formed. Today, there might be ten meters of peat between a raised bog’s living surface and the clay, gravel, or limestone underneath. The oldest, blackest, bottommost peat might have been laid down eight millennia before the birth of Christ.

I was joined at Lodge Bog by Tristram Whyte, a freshwater ecologist with an outdoorsman’s complexion and the cautious manner of someone accustomed to stalking flighty animals. Whyte works for the Irish Peatland Conservation Council (IPCC), a four-person organization established in 1982 to protect a representative sample of the country’s peatlands. Its offices are located in converted stables on nearby Lullymore Island, a rare zone of solid, fertile, mineral land amid the surrounding bogs. For centuries the “island” was a place of refuge, connected to the outside world by a handful of hidden causeways. Its earliest settlement was a monastery founded in the fifth century and purportedly visited by St. Patrick, whose “footprint”—a heel-shaped dent—is still visible on a limestone boulder.

It was early autumn, and the bog, like the trees we could see on Lullymore, was relinquishing its green. Its colors were now khaki, beige, gold, crimson, ginger, and—where peat was exposed or water had pooled—molasses brown or oily black. Small hummocks supported species that favor drier ground: russet-stemmed bog cotton, whose fluffy white bolls would constellate the landscape in spring; gray-green heather, or ling, which in August would crown the knolls with blooms of royal purple; devil’s matchstick, with its livid pustules of scarlet fruit; and tiny, tentacled, carnivorous sundew, its glue-trap leaves primed to enfold insects. The wetter areas were dense with sphagnum moss, the bog’s dominant and formative vegetation, its stems tangling deep into the water. So absorbent is sphagnum that during the First World War it was harvested by the ton for use as a surgical dressing.

I followed Whyte across a duckboard pathway the IPCC had installed toward the center of the thirty-five-hectare bog. He crouched to examine the plant life. “You’ve got your ling here, you’ve got sphagnum, this is magellanicum—you see how it’s got a very stellate capitulum?” He pointed to the star-shaped head of a particular species of sphagnum. “And that’s papillosum, another species of sphagnum; we have bog cotton; Eriophorum vaginatum; and see these little things like barley? That’s bog asphodel; the Latin is Narthecium ossifragum . . . ”

“Hand Cut Turf,” by Amelia Stein © The artist

Despite the profusion visible to Whyte’s knowledgeable eye, the source of Lodge Bog’s ecological value is its relative sparseness. “Because everything’s so specialized you get fewer species,” Whyte said. Many of those species, like the sundew, live nowhere else. This unique flora, I reminded myself, once covered almost the entire Bog of Allen.

Under normal conditions, a plant removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis; when it drops its leaves or it dies, that carbon is returned to the atmosphere through decomposition. But things are different in a bog. In anaerobic, waterlogged conditions, plants die without rotting. Rather than returning to the atmosphere, the carbon is stored. This means that bogs exert a net cooling effect on the climate. It also explains peat’s historical use as a fuel source, both in domestic hearths and, more recently, on an industrial scale by Bord na Móna, the energy company whose excavated bogs have dominated the Midlands since the late 1940s. Today, it is one of the region’s principal employers.

Peatlands like those managed by the Bord, as the company is commonly known, are the largest carbon stores not only in Ireland, but anywhere on the terrestrial planet. In all, they contain roughly twice the carbon of the world’s forests. Estimates vary, but one report suggests there are 455 billion metric tons of carbon in the Northern Hemisphere’s peatlands alone, equal to roughly half the carbon in the atmosphere. When a bog is drained or otherwise disturbed—in the course of commercial extraction, or domestic cutting, or agricultural improvement—the peat begins to dry and decompose, releasing the carbon it has accumulated over thousands of years. A two-meter-deep hectare of active peatland is estimated to extract almost a metric ton of carbon from the air per year and to store up to eight thousand metric tons overall. If drained, that hectare would release an estimated six metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

Since the founding of the Turf Development Board (the Bord’s predecessor) in 1933, peat has become a crucial power source in Ireland; during the oil crisis of the early 1970s, it provided as much as 40 percent of the country’s electricity. But peat has never been an efficient fuel—a recent assessment found that it accounted for less than 8 percent of national electricity production, but as much as 20 percent of the sector’s carbon emissions. Last year, Ireland’s Climate Action Plan conceded that the country was “way off course” and vowed that by 2030 at least 70 percent of its electricity would come from renewable sources, establishing the abandonment of peat fuel as national policy. The Bord had already announced in 2014 that it expected to stop extracting peat for fuel by 2030, but as climate breakdown has accelerated, the company has been forced to scale back far more quickly than planned, and has eliminated hundreds of jobs. The impact on the Midlands economy and working culture has already proved devastating, but even a radical transformation in energy policy will not undo the ecological damage that peat extraction has caused.

“Fifty percent of Europe’s raised bogs are in Ireland,” Whyte told me, as we walked back to the car. “We have a legal obligation to protect them, but less than ten percent are deemed worthy of conservation, because they’ve all been impacted.” The Bord plans to “rehabilitate” some 77,000 hectares of its depleted bogs—mainly by rewetting them and abandoning the sites to nature—but many conservationists think this is insufficient. In Whyte’s view, “Rehabilitation is not restoration; it’s just stabilization.” Those sites may cease to emit carbon, but the living bog will not return.

From Carran Hill to Sligo, by Nick Miller © The artist. Courtesy Oliver Sears Gallery, Dublin, and private collection

If Ireland’s national consciousness can be sought in the matter of the country’s terrain, it might be found in its bogs. Rainfall makes Ireland one of the boggiest countries on the planet, with peat covering 17 percent of its land. With an extraordinary ability to preserve anything that might fall into their depths, the bogs are a museum of Ireland’s deep past. Among the items dug up from the Bog of Allen: casked butter that has scarcely decayed since it was stowed centuries ago; two-millennia-old leather shoes, which look as if they were unlaced yesterday; a Psalter, still legible after eight hundred years underground. The Bord has a partnership with the National Museum of Ireland, whose archaeologists manage such finds, many of which have emerged in the course of the company’s excavations.

For the poet Seamus Heaney—a kind of laureate of the bog—the landscape always had a “strange assuaging effect . . . with associations reaching back into early childhood.” The bog was liberty and community, as well as labor. This ambiguous, borderless terrain—neither living nor dead, wet nor dry, public nor private—has never been politically neutral. Ireland’s bogs were often viewed by city dwellers as fundamentally moribund: economic and cultural voids, the refuge of brigands, outcasts, and hermits, synonymous with a semi-bestial peasantry—“miserable and half-starved specters,” according to one nineteenth-century account. In folklore, bogs are the lairs of the shape-shifting púca—an 1828 study of fairy mythology called them “wicked-minded, black-looking, bad things”—while in Edna O’Brien’s classic 1960 novel The Country Girls, the protagonists are contemptuously dismissed as “fresh from the bogs.” Throughout much of Irish history, the bogs were also seen as impediments to economic progress. In 1731, an act of Parliament was passed to “encourage the improvement of Barren and Waste Land, and Boggs, and Planting of Timber Trees and Orchards.” By the mid-nineteenth century, some thirty thousand hectares of bog had been reclaimed. Nevertheless, a geologist in Bram Stoker’s 1890 gothic novel The Snake’s Pass, quoting a former archbishop of Dublin, still complains: “We live in an island almost infamous for bogs, and yet I do not remember that anyone has attempted much concerning them.” This was not to say that the bogs were irredeemable. “We cure a bog both by surgical and medical process,” Stoker’s geologist continues. “We drain it so that its mechanical action as a sponge may be stopped, and we put in lime to kill the vital principle of its growth.” In theory, the process was straightforward: cutting networks of drainage ditches into the heart of a bog could dry out the peat, which could then be fertilized with lime, manured, and plowed. A “worthless” bog was “cured.”

But a bog is a product of climate and topography; it wants to be wet, just as a lake or a river does. Only through a tremendous, often uneconomical, investment of human energy could a bog be turned into a field of potatoes or a grazing meadow. Fuel, however, was another matter. Turf (the term given to peat cut for domestic use) was the very stuff of the bog, and if impoverished tenant farmers confined to such intransigent land had any advantage, it was the ready availability of free fuel.

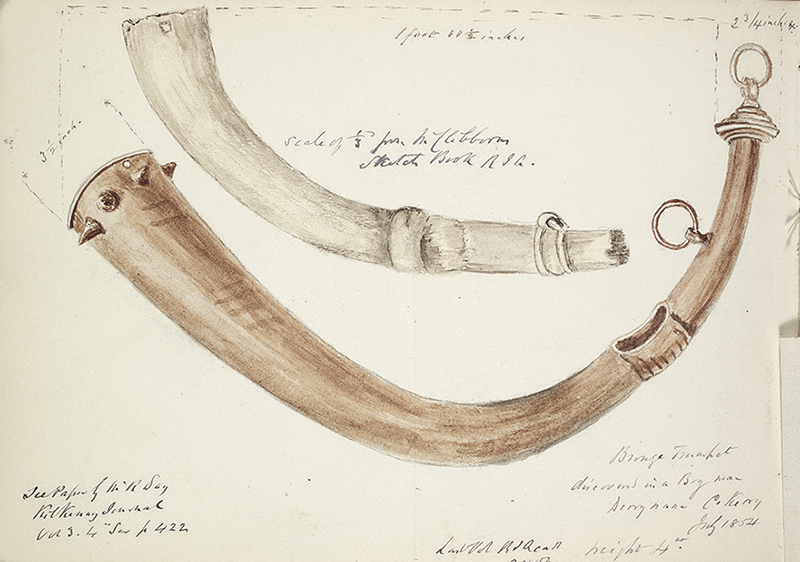

Traditionally, once a bog had been drained, the living surface of plants and roots—the scraw—would be pried away and the exposed peat dug out using a spade with a wing on one edge called a sleán. Summer by summer, an escarpment of peat perhaps two meters high would advance from the bog’s edges toward its center, like an island being eroded by the sea. Once removed from the bog, the brick-size sods of turf were spread out to drain for ten days or so, then stood up to dry in inward-tilting circles of five or six sods each—a process called footing. These assemblages of footed sods are still a familiar sight on Ireland’s private bogs—of which there are hundreds—though these days the sods are formed from macerated peat, machine-excavated by contractors.

By the end of the nineteenth century, bogs had come to function in British-ruled Ireland as a metaphor for a defiant national character. For advocates of British authority, reclaiming bogs was a way of subduing that character; for nationalists, the peatlands, as a potential domestic industrial resource, represented economic freedom. In 1946, after the obstruction of coal imports from Britain during the Second World War made the need for fuel self-sufficiency undeniable, an expansion of the Turf Development Board was announced, establishing a new semipublic company: Bord na Móna, “Peat Board” in English. An acerbic Irish Times columnist called the name “an atrocious neo-decadent Irish title,” one that lent a phony air of tradition to an entity “set up for the purpose of incinerating large sections of your strictly limited Irish patrimony.” But incineration at such a scale demanded a workforce to match, a welcome development in a region of historically scant employment. “Those who got jobs in Bord na Móna didn’t have to emigrate,” one Bog of Allen resident told me. “Lots of my relations went to England, America. The ones who were in Bord na Móna, they were staying at home.”

The postwar years saw the transition from sod peat—bricks cut by hand from the bog or formed in a mechanical extruder—to milled peat, a grainy, crumbly substance industrially scarified from a bog’s surface. The milled peat is then either sent directly to power stations or ground into powder and compressed into oblong blocks, to be sold as domestic fuel. Ask most people in Ireland what the Bord means to them and they’ll describe 12.5-kilogram “bales” of molded briquettes embossed with the letters bnm. Brittle as coal and bound in polypropylene strapping, they are widely available even now. Several Midlanders mentioned to me a TV commercial from 1986, preserved on YouTube. As the fiddle player John Sheahan of the Dubliners plays “The Marino Waltz,” a succession of blissful household vignettes unfold: a man removes his shoes and warms his feet by the fire; a little girl clutches her teddy bear and gazes contentedly into the flames; a woman embraces the lover she’s been waiting for. Each two-second scene is illuminated by firelight—a special firelight, the kind endowed only by peat. Not a word is spoken. The briquette represents a timeless domestic idyll. Peat, the Bord recognized, was more than mere fuel. Bound up in its warmth, light, and odor—even in its mechanically mined and machine-compressed form—were generations of positive associations: comfort, love, the family as a unit of the nation.

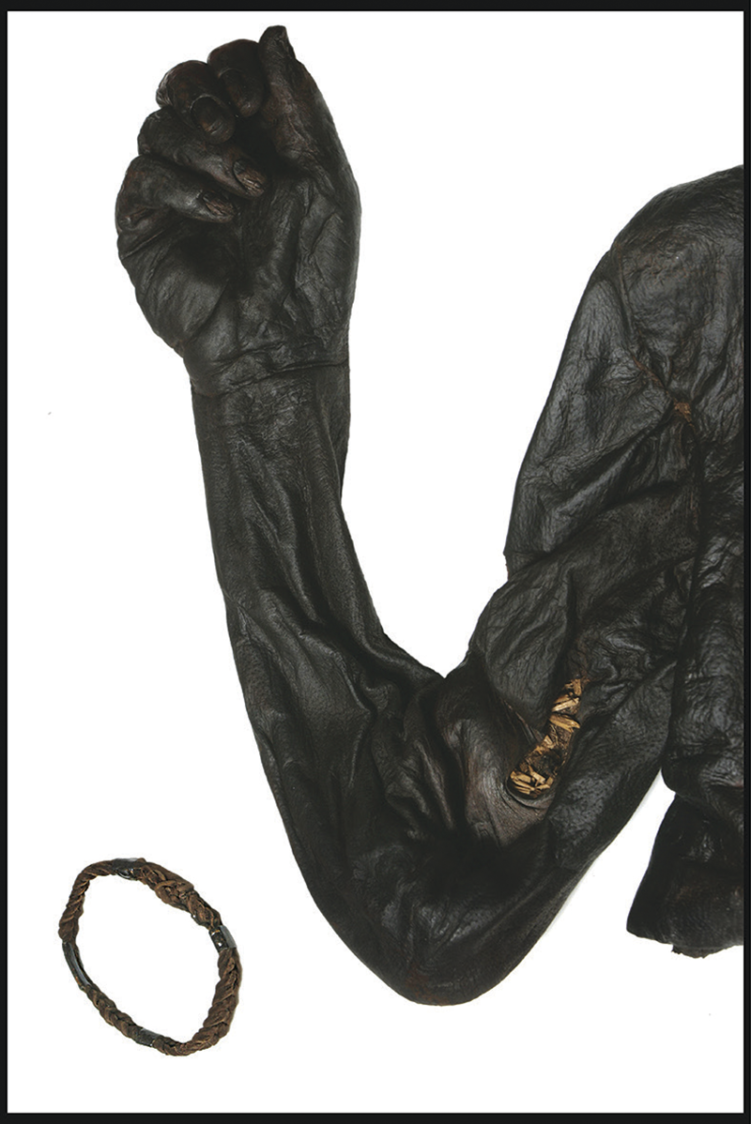

The hand of Clonycavan Man, an Iron Age body found in a bog in Ballivor, County Meath, Ireland © Martin Pope/Camera Press/Redux

In 2003, near Croghan Hill, about twenty kilometers northwest of Lullymore, police were alerted to the discovery of a body. The state pathologist determined that it belonged to a tall man in his late twenties who had been stabbed to death. His nipples had been sliced off and he had been beheaded. Gazing at what remained of his corpse, I could make out the whorls of his fingerprints, his manicured nails (he was not a working man), and the pores of his skin—skin that otherwise resembled an article of tanner’s waste.

Old Croghan Man, as he is known, had been lying quietly in the peat since he was sacrificed more than two thousand years ago. In 2003, he was disturbed during the digging of a drain in a private bog; now he is on show in a vitrine at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin. When I visited, a couple of tourists joined me in the dim cubicle. One of them shuddered, slipped an iPad from her bag, and took a photo. I couldn’t help but feel there was something intrusive about our gawping. A notice informed us that:

Twisted hazel ropes known as withies were inserted through cuts made in the upper arms and may have been employed to fasten down the body to the bottom of a bog pool.

The bogs from which such bodies have been recovered often lie, as Croghan Hill does, on the boundaries between ancient kingdoms, no-man’s-lands of uncertain sovereignty, where a life might be made to vanish.

“Why did they bury the bog bodies there?” asked Ray Stapleton, the manager of Lullymore Heritage and Discovery Park, when I met him the following day. “Because it wasn’t tribal land. It was seen as an outlying area. The bogs have always been wild.” As its website explains, the park is “the only attraction in Ireland offering a comprehensive insight into the Irish peatlands and the people living around [them].” We were sitting in Stapleton’s office, the cataract of rain on the roof so noisy that we had to raise our voices. He told me that he had been born in nearby Rathangan, a village established by Quakers that has been dominated by Bord na Móna since the 1940s. “It was like the Wild West,” he said of the town’s heyday, when hundreds of men from all over Ireland were brought to the Midlands to cut peat for the nation’s new power stations. Stapleton grew up cutting turf each summer on his family’s plot. “I knew the bogs were different,” he said. “You could find newts, dragonflies the size of your hand.”

The Heritage and Discovery Park was founded in 1993, partly to create local jobs following a series of cuts at the Bord. “They had more modern machinery and didn’t need as much manual labor,” Stapleton told me. The park’s exhibition, with its bearded Neolithic mannequins and dioramas, introduces the natural and industrial history of Lullymore while, beyond the café and miniature golf course, visitors can follow a “biodiversity boardwalk” to a flooded cutaway bog. “What we’ve done is let the water back in,” Stapleton said. “You just let nature take it back.”

A shoe found in a bog in Cookstown, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

He conceded that the legacy of the Bord’s activity in the region was environmental ruin—the peat was largely gone and would take centuries to return—but maintained that the company extracted something more than jobs or energy from the bogs. “That was us saying we’re an industrial country, a modern country; we’re able to provide out of our own resources—we don’t need British coal.”

Most of the park’s overseas visitors are German, which Stapleton attributes to their own affinity for peatland (technology pioneered on German bogs is still used by the Bord). British tourists have dropped off since Brexit, and few Americans venture so far from the established sightseeing trails. He admitted that it’s a difficult sell: “You’re not going to the castle, you’re not going to the Wild Atlantic Way, you’re not going to the Cliffs of Moher, you’re not going to Kilkenny. . . . You’re going to the bog.”

When the Bord’s last bog closes, Stapleton would like to see the greater part of the Bog of Allen rewetted, allowed to return to wildness, and promoted as a green tourism destination, a kind of Irish safari park. “I often wonder what would it be like if we hadn’t had to use our peat. I would love to have seen it when it was twenty feet up, like a big cloak. That’s what the poet Matthew Farrell said; he said the bog was like a cloak, surrounding Lullymore, protecting it.”

Later that week, I read Farrell’s 1860 poem. It’s partly a wheedling encomium to Lullymore’s landlord, William Murphy, but also an earnest, if sub-Wordsworthian, celebration of the “Inland Isle” ’s girding bog:

Its texture of the richest brown,

Set here and there with tufts of down,

Embroid’rd o’er with heath bell trees

And these bespangled o’er with bees

With silky folds of mossy beds,

Like pillows made for angels’ heads,

With mirror lakes divided through,

Where countless stars reflect their hue.

Turf drying in the Bog of Allen, Ireland © Design Pics/Alamy

Liberty Hall, the Dublin headquarters of the Services, Industrial, Professional, and Technical Union (SIPTU), is a sixteen-story tower block on the north bank of the River Liffey. Hand-painted on a metal shutter covering a ground-floor window are the words of James Connolly, the union leader who helped orchestrate the 1916 Easter Rising: “The Irish people will only be free when they own everything from the plough to the stars.” I was there to meet Willie Noone, SIPTU’s energy-sector organizer and a critic of how Bord na Móna and the government have managed the termination of the peat industry.

“Years ago, people were put off the land by the English,” he told me, in a conference room overlooking the river, “and it’s built into the psyche that if you have land, you protect it.” As we talked, his phone throbbed sporadically with incoming emails and texts—he was participating in a climate-crisis debate that night on RTÉ, Ireland’s national broadcaster. A Midlands native, Noone also grew up hand-cutting turf on his family’s bog. “When I was young I hated it, because it was seen as a chore, something you had to do—it was dusty, it was dirty, you’d rather be off doing something else.” But having returned to the Midlands after stints living in England and Australia, he is one of the few people who still cut and dry peat for their own hearth. “It’s like Guinness,” he explained. “I’ve never heard anyone who drank their first pint of Guinness and thought it was lovely. But if you go to any pub in the country, you’ll see twelve old men at the bar, and you’ll probably see twelve pints of Guinness. It’s an acquired taste.”

The Midlands has tended to be viewed as peripheral, despite its proximity to the capital, but the region was transformed entirely in the 1940s by the establishment of the Bord. “These weren’t ordinary jobs,” said Noone. “These were good jobs, real jobs, pensionable jobs, jobs for life, skilled jobs.” The development of large-scale peat extraction had the dual benefit of strengthening Ireland’s energy security and summoning thousands of jobs out of soil that historically had almost no economic value. Much of the Midlands still consists of small farms eking out an existence from land that—precisely because of its peat—remains marginal.

A bale of Bord na Móna peat briquettes © Irish Photo Archive/Lensmen Photographic Archives

Peat extraction, like farmwork, is seasonal, mostly taking place between July and September, when drier weather allows machines to access the bogs and the milled peat to dry. Most Bord contracts are for ten months per year or less, and permit a good deal of flexibility. “That actually dovetailed in with the way of life in the Midlands,” Noone said. Bog work allowed Midlands farmers to earn a regular salary while continuing to maintain their own farms. “Between the two of them you had a good living: you could look after your mum and dad; you could send your kids to college.” In other words, employment with the Bord offered a solution to the poverty and isolation that had been ingrained in the Midlands for generations, while keeping the population on the land. With the end of peat extraction, said Noone, “all those farms go back to being uneconomical.”

In late 2018, the Bord announced that it was seeking to dismiss up to 430 of its 2,200 employees in a voluntary-redundancy program. A year later it was announced that two of Ireland’s three remaining peat-burning power stations would close at the end of 2020, as part of what the government called an “accelerated exit from peat” that would see two million fewer metric tons burned each year. By then, many employees had already taken voluntary-redundancy packages: the Bord paid out almost $46 million in voluntary-redundancy compensation in 2018 alone. The Bord also established a “just-transition fund” of $12 million for retraining the newly unemployed; but for most of the company’s workers, whose average age is fifty-six, it was too late to change careers. “The problem with the Midlands is that it’s all bogland,” said Noone, “and there’s not too many things you can do in bogland.” (In April, a further 230 Bord employees were “temporarily let go” because of the COVID-19 crisis.)

With demand for briquettes also declining, Noone estimated that about seven hundred jobs had been lost so far, and believed more would follow. Given the millions of metric tons of milled peat already stockpiled on the bogs, and the uncertainty surrounding the remaining power station’s future, most of the Bord’s land will fall silent this year. The machinery will be sold off or scrapped, and the degraded bogs will be transformed into wind farms or reclaimed as wetlands.

Rain was falling heavily upon the Bog of Allen. I stood alongside Michael Kearney, a former Bord na Móna employee, at the edge of a desert of black. In front of us, parallel runways of exposed peat fifteen meters wide extended more than a kilometer into the hazy distance. Each strip was separated from its neighbor by a drainage ditch about two meters deep, its bottom bright with water. Running along the edge of every tenth bay was an embankment of stockpiled peat three meters high. People often describe the process of removing peat from a bog as “harvesting,” but though a bog may look like a field ready for sowing on Google Earth, up close the process resembles harvesting about as much as an array of wind turbines resembles a farm. It’s more like open-pit mining. Still, looking out at the black expanse, Kearney had the air of one admiring a garden tended over a lifetime. When I suggested I grab my umbrella from his car, he suppressed a smile. “You wouldn’t see many umbrellas on the bog.”

This was Ballydermot Bog, which Kearney managed for the Bord for twenty years before he retired in mid-2018. A cutaway bog like Ballydermot needs to be closely monitored. It may be dead, but it is mutable and moody. Its nature can change from hour to hour, and the amount of peat it yields on any given day can differ wildly from that of neighboring bogs.

A bog manager’s enemies are water and fire. Heavy rain makes a bog too soft to be worked safely—it can take days to recover sunken machinery. Bog men still talk about 2012, the worst year in the Bord’s history, when the summer rains were so intense that by winter the power stations were close to exhausting their reserves. “If we’d had another year like 2012, the power stations would have closed,” said Kearney. But the following summer turned out to be a record breaker: dry and hot month after month, putting the bogs at risk of catching fire. Blazes triggered by sparks from machinery or spontaneous combustion have caused millions of dollars of damage to the Bord’s bogs. For that reason, part of a manager’s job is simply to watch. When a fire breaks out there is nothing to be done but drive a bulldozer onto the stockpile and attempt to smother the flames with more peat. “A fire’d be gone out and after twenty minutes you’d see just a little wisp of smoke,” said Kearney. “You could spend all night watching it.”

As we returned to the car, the deluge gradually gave way to a fine, directionless drizzle: brádán in Irish, misty rain. We passed a comparatively pristine margin of uncut bog, a tussocked carpet of mosses, grasses, and heather not unlike Lodge Bog. “This is the way the bog was,” Kearney said without sentiment. Before Ballydermot was excavated in the 1940s, he reckoned, its surface would have been ten meters higher than it is today—the height of a two-story building. “We’re actually down to the lack.”

A bronze trumpet found in a bog near Derrynane, County Kerry, Ireland. Drawings by William Frazer, after George V. Du Noyer, circa 1890. Courtesy National Library of Ireland, Dublin

“Lack,” or “lac,” or “lak”—nobody I asked was sure of the correct spelling—is a regional term for the ground under the peat, far below the natural organic surface of the earth, which thousands of years ago would have been the bed of the lake from which the bog developed. Perhaps the word derives from “lake,” but it appears in neither Irish nor English dictionaries. Looking back into the excavated void, the bog’s floor of gravel and limestone exposed, I had a momentary sense of being on the bed of a drained ocean—the dark mass overhead crushing in its absence.

It was just a few minutes from Ballydermot Bog to Kearney’s home, in the village of Clonbulloge. We drove back through the rain—clagarnach now, a torrent—along the route he’d taken almost daily for twenty years. “One of our managing directors actually worked his way up from working on the bog as a general operator,” he said. And now? I asked. “They wouldn’t know what a bog looks like.” A few years ago, Kearney said, the Bord hired a consulting firm to improve efficiency. “We had to put a flowchart up in the office. One lad had worked for PricewaterhouseCoopers, the accountancy firm. We had to tell him what we did on the bog from start to finish, and he came back in six months’ time to tell us how to do it better.” He uttered the final word with a certain dryness.

Kearney’s home was a smart white row house on the village green. A sign read tidy towns bronze-medal winner. As we entered, I apologized to Josephine, Michael’s wife, for dripping water on the floor. “As if we aren’t used to that,” she said, leading me through to the kitchen. By the door to the backyard, brick-size sods of dried peat were stacked against the kitchen counter. This same peat was blazing in the kitchen stove, and there was more stored in the shed, and more still—twenty metric tons, to last the winter—in another outbuilding.

“You’ll have a slice of toast,” she said, dropping bread into the toaster. She left us alone for a moment, returning with a framed black-and-white photo of a handsome, smiling middle-aged couple on a peat bog. The woman was seated on a bench cut into a cliff face of peat. In front of her was a folding table on which stood a tin kettle and a jar of Bovril. The man, atop the uncut bog behind her, was clutching a sleán. “Daddy and Mammy on the bog,” said Josephine, fondly.

Nobody ever believed the peat was depthless, or that its removal at an industrial scale was anything less than violence done to the land and the country’s “strictly limited Irish patrimony.” But even despoliation can look like an act of largesse in certain circumstances. If there is fatalism among the Bord’s workers now, it’s only because they know that the company’s raison d’être has never been anything but provisional. The “lack” was always there, waiting to be exposed.