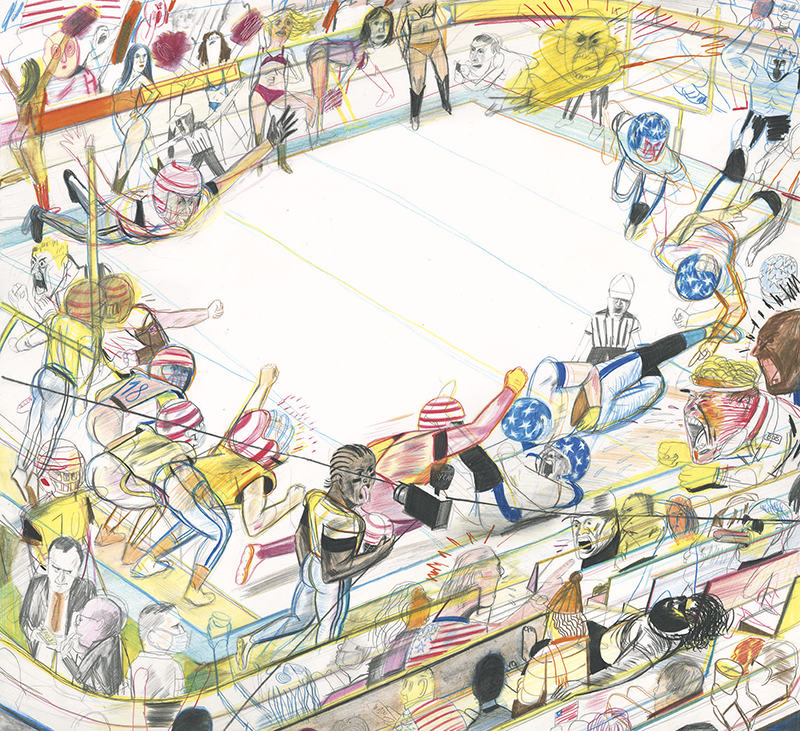

Illustrations by Yann Kebbi

Eight days before training camp was scheduled to begin this summer, the National Football League unveiled a new contrivance for reducing the spread of COVID-19 on the gridiron. The Oakley Mouth Shield was a piece of ventilated plastic that snapped into place behind a player’s face mask, lending him the aspect of a visored knight, or perhaps the Parmesan quadrant of a cheese grater—or so it appeared to me as I watched SportsCenter slack-jawed in quarantine. The NFL could not quantify exactly how effective this Mouth Shield would be—nor could it force players to use it—but such quibbles were beside the point. Even as health experts warned of a second wave, even as the Players Association’s own medical director referred to football as “probably the perfect milieu or petri dish in which to transmit the virus,” the world’s most profitable sports league proceeded as-usual-ish. That was the point. Locker rooms would be reconfigured, of course, team meetings would take place online, workouts would be socially distanced, and fans would be subject to symptom screenings, but football would be played.

Like an irresistible force, the game was moving forward. “I think this is important not just for the NFL or for professional sports,” the league’s chief medical officer told the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine. “What we are trying to do, which is to find a way to mitigate risk and to coexist with this virus, this is really key information for schools, for businesses, for all segments of society.” The NFL saw itself as a case study for how we might cope with the pandemic as a nation. That we might choose to cope by, say, postponing the return of football—this appeared to be unthinkable. Un-American, certainly. A capitulation as bad if not worse than avoiding the mall post-9/11. More football—not less—is the cure for what ails us.

Some two and a half years ago, in what seems like another epoch, it was this same belief in the restorative power of football that led the flamboyant pro-wrestling impresario Vince McMahon to announce that his ill-fated, self-funded football league, the XFL, would be returning for the spring 2020 season. “The audience wants entertainment with football,” McMahon told ESPN, “and that’s what we are going to give them.”

McMahon had tried giving it to America once before, when he launched the original XFL in 2001. (Contrary to popular belief, the X never stood for “Xtreme”; the X always stood for nothing.) McMahon’s startup league put gratuitous violence and base carnality front and center. It had trash-talking commentators and no fair catches, self-caressing cheerleaders and broadcast innovations that aped the graphical stylings of football video games. Team names fell into one of two camps: immaterial animus (Rage, Maniax, Demons) or agents of destruction (Hitmen, Outlaws, Enforcers). There was a defiant sincerity to the league’s deliberate tawdriness, and to its conviction that the XFL’s style of coarse, savage football was somehow purer, more satisfying, than the NFL’s self-important legacy brand.

Unfortunately, the play on the field was bungled and, what’s worse, the violence was inconsistent. After the XFL’s opening slate of games—which drew ratings that were double what NBC had promised advertisers—weekly viewership declined gradually and then suddenly. The games became some of the lowest-rated programs in prime-time television history, neither bawdy enough for the wrestling crowd nor technically proficient enough for football fans. NBC declined to renew its agreement for a second season, and the outfit folded three weeks after what it called the “Big Game at the End of the Season.” McMahon conceded that it had been a “colossal failure.”

Nevertheless, in the years that followed McMahon sometimes hinted at a desire to give the XFL another go. In a 2017 ESPN documentary about the league, a disputatious gleam could be seen flickering in his eyes as he discussed what he felt was his greatest opportunity squandered. “Do you have any thoughts about trying again?” McMahon is asked at the film’s conclusion. “Yes, I do,” he answers. Less than a year later, he relaunched his passion project.

It all seems unreal now, hindsight being what it is and plague time having collapsed into a recursive eddy—yet true it remains: I was a fan of the original XFL, yes, and I was an irrationally avid fan of this year’s do-over. Months in advance, I had marked my calendar for the inaugural New York Guardians contest. Why? Even now I’m unsure. I like football fine, even if football has mostly just hung around my Fridays, Saturdays, Sundays, holidays, weddings, and funerals like an odorless gas. I think maybe I possessed a vague intuition that this second iteration of the XFL would be important; I understood it as an unlikely proxy for . . . something. In any case, when the day finally arrived this February, I lined up with a couple dozen others at the Port Authority Bus Terminal for a shuttle to MetLife Stadium in New Jersey.

Alongside me in the depot’s unctuous gloom: Hardcore football purists decked out in prepurchased Guardians memorabilia. Sweaty inveterate gamblers dressed lightly under heavy coats, periodically checking the closing odds on the official XFL app. Quibbling and let us say physically indelicate pro-wrestling connoisseurs. And those like myself: moderate to intense sports fans ranging in age from adolescence to early dotage. Some of us had fond if irony-washed memories of the original XFL; others were too young for that. Some wanted a decent minor-league contest; others had come for a shitshow. What brought us all together, what made us the target audience for this second go-round, was that we were Americans who liked football, and we figured we’d watch some more of it. Why not?

On board, I lowered myself into an empty seat next to a large youth wearing a lanyarded iPad around his neck. He snickered at the XFL pregame show in between bites of a bagel sandwich. The bus doors shuttered; unseen cans of beer rasped. I, too, cracked a Lime-A-Rita tallboy inside the Duane Reade bag on my lap.

It was the first Sunday after the Super Bowl, a day for us citizens to slip the bonds of football fandom and find something else—anything else—with which to occupy our weekends until next season. Historically, this day has kicked off a great national bottoming-out period, a time for Americans—addicts that we are—to cry out from the depths of withdrawal and admit to our total dependence on football. To wit: forty-three of the top fifty most-watched broadcasts of 2019 were football games. Some 150 million Americans tune in to the sport week in, week out. Once the season ends, half of those 150 million Americans watch no sports at all until football returns with the weather, like an inexorable harvest god.

In other words, there’s billions of dollars’ worth of football demand that goes unmet each year. The market, we are told, abhors a vacuum, so why has no one worked out a spring league to rake in some of this cash? It’s not for lack of trying. Entrepreneurs have been chasing the dream for decades. In addition to the XFL, there was the doomed Alliance of American Football, as well as the Spring Football League before that, to say nothing of Your Call Football, the Regional Football League, the Stars Football League, and the International Football Federation. The most successful of these quixotic failures, relatively speaking, was the United States Football League, which persisted from 1982 to 1986. “I’ve never believed that Americans buy chewing gum only in the spring, make love only in the fall, go to movies only in the summer,” USFL founder David Dixon said. “We will play spring football. And people will watch.” People did watch. The USFL was a modest sensation until Donald Trump purchased the league’s New Jersey franchise and forced the league to abandon its spring schedule for the fall in order to compete directly with the NFL. Not long after, the USFL collapsed.

Still, the dream perdures, because it is premised on a seeming certainty: Americans so love football that if you just offer them more of it, the dipshits will no doubt choose to consume it. Even if the play is third-rate, thick with nobodies, and nigh-on unwatchable, it is football, and Americans need football more viscerally than they need any other sport or televisual property. Forget past failures; the problem likely lay with the business model, or the franchise locations, or the calendar window. A winning combination must be out there.

On the bus to MetLife Stadium, the group banter built to a raucous, fraternal roar. I glanced at my seatmate’s iPad; it was playing the thirty-second XFL ad that ran during the Super Bowl, in which a not-quite-recognizable comedian plays a doctor: “I’m here to talk to you about something very serious, and it is serious,” he tells America. “It’s called football-withdrawal syndrome. Football releases endorphins in your brain, and when there’s no more football, there’s no more endorphins.”

The buses disgorged us at the outer limit of the stadium’s parking lot. We walked across empty asphalt toward an abbreviated tailgating section, where those with cars, folding tables, and grips of alcohol had set up before noon. The silky, inflammable scent of lighter fluid hit first, then the Whitesnake. Tailgaters called out to us, and we to them. I made a show of shotgunning my Ritas. An alchemical festivity was in the air—we were creating a fan base ex nihilo.

I attempted a few short Q&As while moving between satellite parties. Q: Why are you here? A: Football weather, bay-bee! Q: What is the name of the other team, even? A: Go Guards, brother! And so forth. Lots of beer-can crushing and cigar smoking. Woo-ing with fists held cheek high. These fans knew to present as “XFL fans.” For one another if no one else.

The February afternoon was cold, bright, sharp to the eyes. Those fans who had sufficiently watered themselves moved with me toward the security checkpoint at the stadium entrance. Along the way, a tailgater in a red hoodie clambered onto an SUV and waited for passersby to stop and ready their phones. A crowd gathered. The young man’s buddies held the long o in “LET’S GOOOOO!” like Mongolian throat singers; they were supplanted by a ragged chant of “Let’s go, Guards!” Atop the SUV, the young man played with the hem of his sweatshirt. Sheepishly, he grinned. Then he squatted, swung his arms, and jumped. For a split second, he hung extended—laid out like an oil-painted odalisque—before crashing through an aluminum table. The crowd roared in agreement: this was how our hot-wired fan base should ride.

Slightly more consideration had gone into the league itself. The XFL was operated by Alpha Entertainment, a venture spun off from McMahon’s World Wrestling Entertainment in 2017. There was no outside partnership, as there had been between the original XFL and NBC, and McMahon’s wrestling associates had no input on football issues—total operational control lay with Alpha. McMahon brought on Oliver Luck, a former NCAA honcho, as league commissioner and chief executive officer, and Jeffrey Pollack, previously a flack in the NFL’s marketing department, as president and COO. When I first read about these decisions, my eyes goggled—here were real, live football people. McMahon was serious this time. No cheerleaders, no sideline buffoonery. “Aside from the name,” commissioner Luck told the New York Times, “there is nothing in common.” The XFL 2.0 would succeed or fail based solely on the quality of play.

The league tweaked the rules for kickoffs, extra-point attempts, and clock management, all in an effort to meet McMahon’s dictate that his games move fast and last no longer than two hours. To further concentrate the terror and agon inherent to football, the XFL not only allowed betting on its games but vigorously encouraged it: the league launched its own free-to-play mobile app, and point spreads and over-under totals ran along the broadcast crawler. Even the announcers discussed (or lamented) their own wagers.

One phrase I encountered often in XFL promotional material was “fan engagement.” And to increase it—or at least prevent disengagement on the part of a certain segment of the viewing public—the league wrote a ban on anthem protests into player contracts. This was McMahon’s idea; he wanted his league to be as “nonpolitical” as possible. “People don’t want social and political issues coming into play when they are trying to be entertained,” he explained. He also stated his intention of “evaluating [each] player based on many things, including the quality of human being they are.” Ergo, felony convictions would disqualify potential XFL recruits.

And recruits they were—to the league, not to specific teams, as the XFL 2.0 did not operate under a franchise system like the NFL but controlled all its teams centrally. Parity was the goal, and as such quarterbacks, unlike other players, were assigned to each of the eight teams, an attempt to spread talent evenly, if thinly, like half a pat of butter on toast. The XFL also managed a shadowy Team Nine, complete with full roster and coaching staff, which practiced weekly to keep emergency substitutes physically and mentally ready. Any player cut from his XFL squad was added to Team Nine, to be potentially recycled back into competitive play.

Small comfort, perhaps, when the money was so meager: base pay started at a biweekly rate of $2,080. A bonus of $1,685 went out to each week’s active roster players, with another bonus of $2,222 if their team won. Doing the math, I found that an XFL starter on a perfectly mediocre squad could expect to earn $27,040 in base pay plus $27,960 in bonuses, for a total of $55,000, or a bit more than a fresh-out-of-college personal assistant might make in Manhattan. Top quarterbacks fared better, earning more than $495,000, the minimum NFL salary, but most collected something in the neighborhood of $125,000—decent accountant wages, then. The league provided health insurance, which was nice.

Still and all, these were football jobs. Football jobs that would not have existed otherwise. Bear in mind that every year around Labor Day, the preseason roster of each of the NFL’s 32 teams gets slashed from 90 players to 53. Of the 2,900 players who sign training camp contracts, only 1,700 or so make it to the Week One sidelines. There are thousands of prospects kicking about—and more each year, as only a couple hundred college players get selected in the NFL’s spring draft—who have given a decade of their lives to football in return for a gross sum of zero dollars. Very few of those who harbor professional aspirations would scoff at the opportunity to play the game for money.

For its part, the NFL has been tepidly supportive of the idea of a spring league. When asked about the XFL’s reboot, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell said, “I look at it as a positive because people are investing in football. They’re investing a significant amount of capital to create new football leagues. That just shows you the popularity of our game. . . . That only creates greater opportunities and, frankly, more fans.” When it comes to football and Americans, he’s saying, there is no such thing as choice overload. Never can have too much of a good thing.

Half an hour before kickoff, MetLife Stadium’s monumental concourses remained mostly empty. What fans there were mobbed the souvenir kiosks, where some snapped up officially licensed trifles—shot glasses, knit hats, die-cut magnets—with the zeal of brokers on the futures trading floor. As I took my seat behind the east end zone, I surveyed my surroundings: A smattering of families, snacks at the ready. Fans of McMahon who flaunted their cultural capital by way of his products—vintage WrestleMania tees as well as authentic he hate me jerseys from the original XFL. Centerless voids of petit bourgeois bros. Couples on dates, dear God.

Beyond this tableau, the announced crowd of 17,000-plus was filing into the lower bowl. Loud snareclaps from the PA system reverberated around the roped-off upper decks like sweeps of sonar. At midfield, the logo painted onto the artificial turf was not that of the New York Guardians (a hissing varmint accessorized with either speed lines or a pharaoh’s nemes and meant to evoke, I think, a gargoyle) but that of the XFL itself. Beneath it was the league’s motto and professed raison: for the love of football.

We lustily booed the anonymous Tampa Bay Vipers trotting onto the field, then roared for the Guardians in turn. The Jumbotrons displayed the official hashtag, #OnDuty, which we were urged to use in our social-media posts. The idea, I suppose, was that we and the players alike were seeing out some kind of civic responsibility.

On the field, uniformed soldiers unfurled a huge American flag. A ten-year-old girl powered through the anthem. Everyone stood, and my section sang along with the final two couplets. “For the love of football, we are officially on duty,” announced the announcer. The kicker minced toward the tee, and with the resounding gourd thump of the booted ball: game on.

In order to minimize violent collisions during kickoffs, the XFL stipulated that both teams’ return units must remain five yards apart until the kick is fielded. This produced a shunted crush of players that was strange to watch until it wasn’t: the New York returner found a hole and, running with all the speed he could manage, advanced forty-one yards into Vipers territory. From there, the Guardians short-passed methodically, dinking and dunking until the drive was capped with a quarterback sneak across the goal line. The crowd went delirious, fogged itself up.

The XFL 2.0 had also scrapped kicking for extra points. Instead, a team could run a one-point play from the two-yard line, a two-point play from the five-yard line, or a three-pointer from the ten-yard line. The Guardians opted for a one-pointer, ran it in, and all of a sudden, MetLife was suffused with a sense of legitimacy.

But once the squads had traded a turnover and a punt, the spike in energy regressed to its mean. I was reminded then how much attending a football game, in a word, blows. What makes the sport such excellent television is also what makes it very difficult to watch live: the field of play is a flat and shifting foreground for the ball. Rather than invite the spectator’s eye to widen, as baseball does, football forces you to focus. The fan is asked not to laze and enjoy but to lean forward and concentrate, goddamn it, on the clusters of men operating in a state of constant flux, equal cogs in a human machine. Squinting and fretting play after play, knowing that turnovers and touchdowns are possible with each snap, the spectator cannot help but clench, unclench, and clench again, as though being jolted with a muscle stimulator.

Also, it was cold out there, and in addition to the ten-minute halftime, there were scads of team time-outs, TV time-outs, injury time-outs, official replay time-outs. Roughly two thirds of the proceedings were given over to players and coaches and trainers milling about on the field like crew members between takes. In this way, attending a football game feels virtually indistinguishable from being cast as an extra in a movie about a football game. You sit there scratching yourself, waiting to be called back to your role, before finally rousing into character when you hear the quarterback’s clapper board call for “Action!” And, just like the extra, what the spectator sees playing out before him bears only the coarsest resemblance to the polished multicam production that winds up onscreen. In a sense, then, we were #OnDuty. We were providing the viewers at home with broadcast ambiance and background verisimilitude. We were playing our part in the production of football.

The game drew on, 7–0 Guardians, then 14–0, 17–0, and it became increasingly difficult to tell whether New York’s defense was superb or Tampa’s offense just stank. The crowd chanted “M-V-P” at ex-NFL player Matt McGloin, the Guardians’ starting quarterback. A father behind me commented that it would have cost $500 to take his family to see the NFL’s Giants do this—well, not this, not win. The crowd chanted “Let him stay!” at security guards ejecting a young man in socks and gray briefs who, having momentarily made it onto the field, was leaning into his arresting officer, hopping up and down, and agitating his (it must be said) mondo dong. At the beginning of the fourth quarter, the Guardians forced a fumble and returned it for a touchdown. After that, they stopped Tampa’s offense again. The clock burned, and New York’s defensive linemen snuffed out opposing ballcarriers with the speed and relish of truffle hogs. Victory! A stinging wind paced the concourse as we filed out.

In its opening weekend, the XFL averaged between 2.4 and 3.3 million domestic viewers, numbers nowhere close to the 12 million it garnered in its 2001 debut, but more or less in line with what the Alliance of American Football got in 2019. The true measure of the league’s viability, experts said, would be its TV ratings in its second week and thereafter.

For the Guardians’ second matchup, an away game in D.C., I invited my friend Jay over to watch. We made queso fundido, we half-listened to the pre-match analysis, we briefly discussed the health scare emerging in China. Then we popped some Silver Bullets and settled into the business at hand. The Guards’ first-half possessions concluded as follows: punt, fumble, interception, punt, punt. Their play was inept and frankly grating. Incomplete pass . . . run for no gain . . . false start . . . it was as entertaining as watching a man fail to turn over his car’s ignition. The displeasure of it gave way to absurdity, out of which emerged a mutual, confounded glee. “Dude!” we shouted after each ingeniously botched snap.

“This is why the Arena League is around but nobody gives a shit,” Jay said. “Same thing with the Canadian league. At least with college you’ve got future NFLers.”

“This is the slush pile of football,” I agreed. “No diamonds in the rough, because it’s all rough.”

We were hunched at the edge of my couch, our elbows on our knees.

“That,” Jay said, “plus they want you to sit outside in February.”

“To watch desperate players concuss themselves some more for the chance at an NFL practice squad,” I added.

Jay killed his beer. “Like watching someone tunnel out of prison with a spoon.”

The broadcast team tried to wring a narrative from this travesty. Camera angles shifted constantly—here a wide shot, a look at the defensive alignment via Skycam, now a sideline interview—in an attempt to improvise a plot arc. Often they cut to one of their new perspectives, live feeds from the offensive and defensive coordinators’ booths. A voyeuristic frisson accompanied these cutaways—the OC just called Green Right X Shift to Viper Right 382 X Stick Lookie!—until one remembered that play calls were veiled in an argot as uncrackable to the layperson as church Latin was to a serf.

It is a football truism that understanding of the game ripples outward in concentric circles. The players on the field know what football is; the coaches know it, too, though at an abstract level; the managers and trainers know it still less; broadcasters, executives, and reporters less than that; and so on out to the average fan, a veritable ignoramus who enjoys the sport for reasons he can neither articulate nor altogether comprehend. Football is a mystery cult, and initiates have more than a little disdain for outsiders.

No other professional athlete is tested as brutally or scrutinized as relentlessly as the football player, whose every move on the field is part of a top-secret operation as coordinated and high-stakes as a SEAL raid. So perhaps one can take former Indianapolis Colts head coach Jim Mora’s words to a journalist with some humility: “You don’t know when it’s good or bad. You really don’t know. You guys don’t look at the film, you don’t know what happened. You really don’t know. You think you know, but you don’t know. And. You. Never. Will.”

Football’s sociocultural hegemony is funny that way. The average fan has, quite simply, no idea what the fuck is going on. Being even moderately informed would entail access to game film, scouting reports, playbooks, minutes from team meetings. The very structure of professional football—its bureaucratic hierarchy, its Byzantine complexity, its relentless human churn—defies transparency. One might even wonder whether it’s by design. In any event, what we get are meticulously honed parts that have been programmed to run subroutines, the instructions of which are wholly inscrutable, all in service to a commodity that consumers can’t get enough of. Hell, Jay and I might as well have been spectating a malfunctioning production line.

About two million other people were spectating as well—a 30 percent drop in ratings from Week One—when the D.C. Defenders converted a twenty-six-yard field goal, upping their lead over New York to 21–0. “This game is knockout gas,” Jay adjudged. I asked him if he would like to come over and watch the following week’s road contest. He said no, he would not.

Hard seltzers in hand, I rejoined the Port Authority bus line two weeks later, queuing behind a tanned, middle-aged loner in a Guardians sweatshirt and overstuffed cargo pants. This time, I did not wait to board the carriage. Tippling from my can and shifting my weight from foot to foot, I swiped between investment apps on my phone, ascertaining just how much further my SEP IRA had plunged during the stock market’s worst week since 2008.

I had tut-tutted the supposed threat of the novel coronavirus back when Jay told me he’d already bulk-ordered antibacterial wipes and surgical masks. I conceded that, since he was a combat veteran, he was more sensitive to threats than I—but also that I could not see in this newest viral outbreak some terrible and abiding cataclysm. “We should all be more worried about the flu,” I told him, like a goddamned idiot.

By now, of course, the coronavirus had tanked the market and was dominating the news cycle. Yet down in the subterranean concourse, there were no outward signs of concern. Fans were maskless. The bus station’s atmosphere appeared to be teeming only with the usual bacterial chaff. The guy in front of me saw no problem with reaching out and bare-handedly grasping a Chicago Bears supporter while communicating something mock-aggressive in a thick Russian accent.

“Not a Bears fan?” I asked.

“Lions,” he said, turning to me. He wore a graying, patchy beard connected to graying, close-cropped hair.

“I actually went to the first game because I woke up, I was really hungover, I was thinking about going . . . ,” the guy began. I popped a fresh can, handed it to him. “Thank you,” he said, “I’m actually kind of dehydrated.”

“That’s why you get the seltzer,” I replied.

He continued: “So I said, ‘Ah, you know what, fuck it.’ Tickets are like thirty-five, forty dollars. And it was like forty-six, forty-seven degrees. I said, ‘You know, I’m not gonna suffer.’ So I said, ‘Fuck it, I’m gonna go.’ I was really shocked because, in my opinion, I think the product is good. I don’t know any of these players. I really don’t. But it seems it’s competitive. It’s loud.”

His name was Lev, he told me, “which means ‘lion,’ okay?” To Lev, it seemed practically providential that he should move to the United States at seventeen, find an eleven-inch television in the trash, and watch his first American football game—Lions vs. Bears—on Thanksgiving Day, 1979. He fell deeply in love then and there.

As we boarded the bus, I asked whether he had known about the sport before fleeing the Soviet Union. “Absolutely not,” he said. “It was not even trashed in the propaganda.” I took the seat next to his, and replaced our empty cans. Lev explained that he became a student of the gridiron as much as a student of English. His football education had coincided with his civic instruction.

“It’s what separates us from the world,” Lev reflected. “American football is uniquely American sport. It’s kind of, like, fitted into American culture.” I agreed.

By the time the bus delivered us to MetLife, Lev and I had established a comfortable, hollow esprit de corps, like perfect strangers working a shift side by side, deliberating over the one thing we had in common. At the edge of the tailgating zone nearest the security gate, we positioned ourselves next to a dumpster so that we could toss our empties while powering through my remaining cans. Lev talked to me about his Super Bowl bets, a lot.

Meanwhile, the tailgating area was beginning to crackle with malice. A spooky, implicit enmity was thickening about us—the kind that sets in when masses of Americans get real drunk and thus more boisterous about their woundedness, their sneering despair, their desire to see shit go bad at last. I maintained eye contact with a security guard while Lev removed a plastic bladder of whiskey from the pocket of his cargo pants. He suckled from it before sliding it gingerly past his underwear’s elastic to a resting place between his legs. “Thing is,” Lev said while testing the bladder’s fit with a lunge, “and I hate to say it . . . I have a strange relationship with women.”

We proceeded to the metal detectors, where Lev was ordered to empty his many pockets. As I waited, I realized I hadn’t bought a ticket. I told my football-naturalized friend I’d catch up with him, and I wound up paying a scalper $30 for another end-zone seat. Inside, the crowd was appreciably smaller; expanses of negative space separated the few spectators who weren’t massed behind the goalposts. A cold wind rang around the lower bowl like the rubbed rim of a wineglass. We chanted “U-S-A!” during the anthem.

Having lost two games in a row, the Guardians were starting their third-string quarterback, who could at least lob screen passes to his last-resort receivers. Collisions echoed through the stadium, polymers impacting and warping as in a car accident, with about as much force. The PA complemented these tackles by pumping in audio clips of thuds and groans. Frequently, I had to remind myself to watch the play on the field as opposed to the Jumbotrons around the stadium, which were relaying the national ABC feed. For the third straight week, ratings were dropping, as a mere 1.6 million viewers tuned in at home. What they and I saw: Guardians lunging headfirst, play after play, for little money and one final, minuscule shot at the big time, before they were definitively pronounced redundant. “Everyone is needed, but no one is necessary.” That’s one of those old football mantras (“Just win, baby!”) that has entered the wider lexicon because it encapsulates something about our world, too.

Flurries of snow began to dust the stadium. A civilian wearing a mascot-size bunny head (and only the head) danced up to me, gesturing his desire for me to dance as well, which I did. I stopped to applaud an especially violent tackle. I remembered why football is played in the autumn: the scent of the grave pervades it.

So goes much of the sport’s allure. “There’s murder in that game!” marveled the lineal heavyweight boxing champ John L. Sullivan when he first encountered the sport in the 1890s. At the time, a few dozen college boys used to die every year playing football—and eager crowds gathered to watch. The deaths got to be so thick that President Theodore Roosevelt convened a national summit in 1904 for the deliberation of newer, safer rules. Even so, more than six hundred players were killed between 1906 and 1965. To this day, football remains something Americans believe is worth dying for.

And it will kill you; there’s no longer much doubt about that. It’s physics, no more, no less. A head moving at speed x, forced to decelerate to zero over distance y, will always equal a brain sloshing around the inside of a skull. Advanced helmet engineering will never fully mitigate big hits, to say nothing of the repeated impacts that occur along the line of scrimmage with each snap of the ball. These are the lesser knocks that, when they accumulate over seasons of youth, middle school, and high school football, can put even a portly teenage lineman at risk for neurodegenerative diseases like chronic traumatic encephalopathy, known as CTE.

As a result of this dawning awareness of football’s hazards, the junior game has declined. Pop Warner, the largest youth football league, has faced the existential threat of a class-action lawsuit. Participation in high school football has dropped more than 10 percent in the past decade. The demographics have changed, too: black and Hispanic players are making up larger pluralities. Indeed, there’s a strange parallel between those who sign up to play football and those who volunteer for the armed services: both tend to come from certain parts of the country—the South, the Rust Belt, inland California, and Texas—and both tend to know somebody who served before them.

In other words, football has become political. On one side, you have those who believe the total-body hazard inherent to the game is not a lamentable byproduct but the source of its value. More than any other sport—more than any institution save maybe the Boy Scouts—football builds character and molds boys into men, the thinking goes. In fact, the sport’s guiding principles of teamwork, self-sacrifice, mental and physical discipline, as well as its unapologetic demand for excellence, are more necessary now than ever. Football, to its partisans, is an almost industrial producer of stick-to-itiveness, manly camaraderie, respect for authority, and “Life isn’t a hundred percent safe, either”–ism.

On the other side, you have those who see in football “a reflection and reinforcement of the worst things in American culture,” as the former NFL player Dave Meggyesy once put it. Football is a grotesque celebration of the corporate and military ethos of this country. It is our soulless blood sport, typifying everything from civilizational sociopathy to manifest destiny. Why, these detractors wonder, would you want to teach a child how to get back up after being knocked down? Wouldn’t you rather work toward a world in which children don’t get knocked down in the first place? Fetishized “toughness” is but acquiescence to a fucked reality, and we have ordered our very schools around it—the quarterback sits atop the adolescent social pyramid, does he not? Football, ultimately, is a perpetual motion machine for toxic masculinity and the patriarchy, a metaphor that literalizes itself by turning the brains of all those involved into mush.

Then again, football might provide you with an understanding of pain; a satisfaction in knowing it can be withstood and transcended; an appreciation of the body and its limits; an intimate foreknowledge of mortality; a band of brothers; a soldier’s or artist’s affinity with the initiated. The sport might leave you with many things, not least of which is the bone-deep apprehension that a football wants to wobble, but to make it spiral true is a triumph that, however briefly, overcomes the hard condition of the world. Who can say? In the end, it’s up to the players who choose to play the game, the parents who choose to let their children sign up, and the viewers who choose to watch.

Planes banked lazily over MetLife, departing from and arriving at nearby Newark Liberty International. Curious, I checked my phone to see whether it had welcomed any flights from Wuhan before the Chinese travel ban. (Yes—via Shanghai and Frankfurt.) On the field, men galloped terribly against other men. The cold was its own black presence, like the ocean whipping beyond a ship’s gunwale. It was fast becoming too much for me—the claustrophobic violence, the canned sound effects, the hare-headed nihilist—when the third-string QB heaved up a long bomb. His targeted receiver was wide open, streaking into unowned space. We fans rose to our feet, following the arc of the ball’s parabola. The receiver looked over his shoulder, to track the pass into his hands, but it was not forthcoming. The ball had sailed out of bounds several yards behind him. I turned and made for the exit.

During Week Five—halfway through the season—the Guardians drew about 1.5 million TV viewers, half of what they drew in Week One. Those who watched were treated to the team’s most competent performance yet; they appeared to be gelling as they routed Dallas 30–12. That same week, news broke about a Seattle Dragons concessions worker who tested positive for COVID-19. XFL executives mulled the possibility of playing games behind closed doors. A few days later, following the NBA’s lead, the league suspended play indefinitely.

Before the season began, McMahon announced that he was prepared to dump $500 million—several times more than what he and NBC invested in the XFL 1.0—into his revamped league. But as stores shuttered and services dwindled, as shelter-in-place orders went into effect across the country, as an unprecedented number of Americans filed for unemployment insurance—the frivolousness of spring football was suddenly made clear.

On April 3, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “advised” all Americans to wear masks in public. In response to this advice, the president of the United States said: “You can do it. I’m choosing not to do it. It’s only a recommendation.” He was giving voice to a truth we hold to be self-evident: you and I are free to take measures to protect ourselves and others from a deadly pandemic—or not. Just as we are free to batter ourselves about the head and neck playing football for money, if that is what we choose to do. We are free to pay full price to watch others fumble their cognition and mortgage their futures, if such are our druthers. This is the voluntarist conception of liberty that lies at the heart of America, that enshrined football as its civil religion, and that made this nation the hottest of coronavirus hot zones. Choose to pay for health insurance, or don’t. Choose to quarantine yourself for the collective good, or nah. Choose to reopen for business, or risk losing the whole nine yards.

On April 4 and 5, McMahon broadcast his closed-set WrestleMania 36 in direct defiance of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department, which had ordered that the WWE cease its tapings in accordance with Florida’s stay-at-home order. Four days later, the governor of Florida added pro wrestling to the state’s roll of essential businesses, alongside grocery stores and hospitals.

On April 10, the XFL laid off its staff and announced that it had no plans to return in 2021. Within a week, McMahon (alongside Goodell) was invited by Trump to join one of his Great American Economic Revival Industry Groups.

In the weeks that followed, massive demonstrations against lockdown orders broke out across the country. Protesters carried guns as well as pithy signs. let my people golf, read one. my body, my choice, read another, held aloft by a maskless woman. They were crying out for a return to the status quo. Whatever consequences were to follow from the decision to shake it off and get back out there, these Americans were prepared to suffer them—they merely demanded that the choice, as ever, be theirs to make.

One further choice would be theirs to make sooner rather than later: an investment group led by the NFL and Canadian Football League washout turned WWE superstar Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson reached an agreement in August to purchase the XFL and its assets for $15 million, just hours before they went to auction. Johnson told the press that he looked forward to “creating something special for the players, fans, and everyone involved for the love of football.”