State of Exception

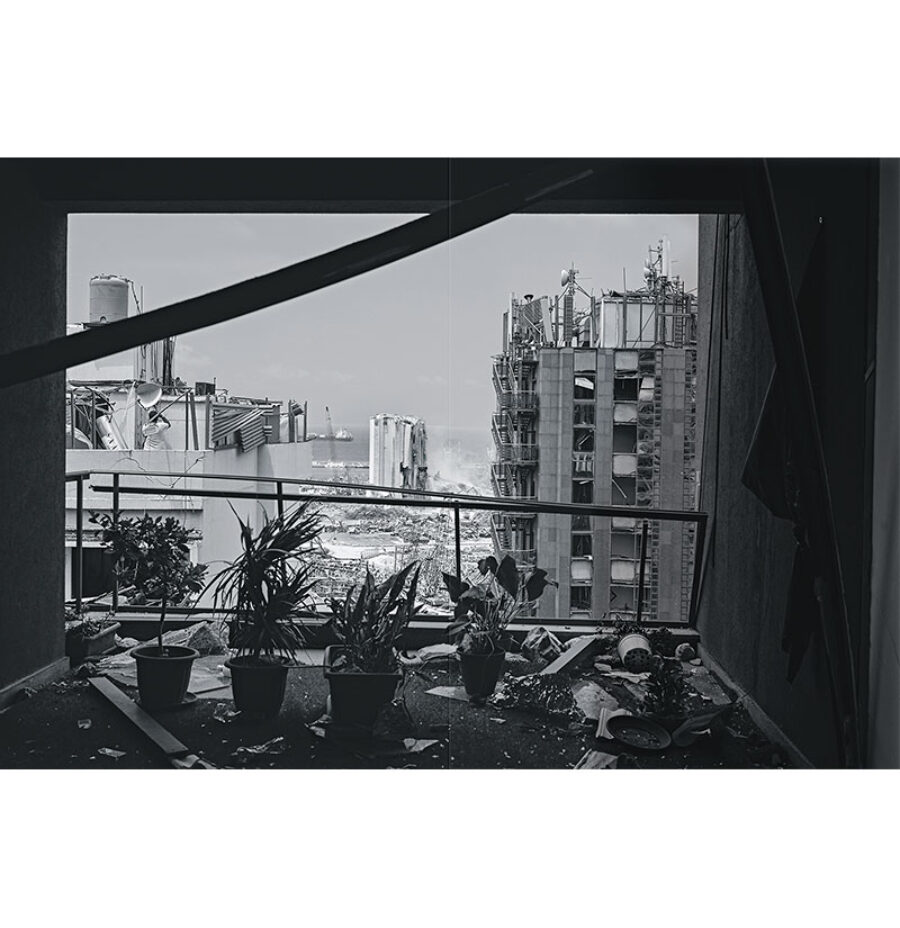

The port of Beirut, as seen from a damaged apartment in the city’s Mar Mikhael neighborhood. All photographs from Lebanon, August 2020, by Nicole Tung for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

On August 4, a blast with the force of a tactical nuclear bomb tore through the port of Beirut. A red pillar of smoke and chemicals shot into the sky as a pressure wave swept across the city at more than 600 miles per hour. The explosion, registering at 3.3 on the Richter scale, could be heard as far away as Cyprus. When the dust cleared, nearly two hundred people had died, thousands had been wounded, and hundreds of thousands had lost their homes. My old apartment building in the eastern neighborhood of Achrafieh was gutted, as were many of the bars, restaurants, and cafés I frequented during the years I lived in Beirut as a foreign correspondent. Lebanon’s largest grain silo and its biggest container terminal—vital in a country where almost everything is imported—were leveled, as were several hospitals already under strain from the coronavirus pandemic. Sandstone palaces and houses dating back to the Ottoman Empire lay in ruins.

Within days, shock and grief gave way to rage. Antigovernment protests that had been flickering since the country entered a financial crisis last fall erupted with renewed energy. Lebanese security forces, which had been largely absent from the cleanup efforts undertaken by local volunteers, emerged to fire tear gas and, occasionally, live ammunition at the crowds. Protesters not only called for removing President Michel Aoun, a former warlord ruling in coalition with Hezbollah, but demanded a wholesale replacement of the entrenched kleptocracy that has run the country since its civil war ended three decades ago. “Everyone means everyone,” they chanted.

Over the past few years, Lebanon’s leaders, many of them former commanders like Aoun, have overseen an escalating series of crises: a huge buildup of trash along the coast, a financial meltdown, and now the explosion. Bureaucratic dysfunction and neglect had allowed some 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate—more than a thousand times the amount used in the Oklahoma City bombing—to be stored in unsafe conditions for years, until it blew away a major swath of the city. But news coverage of the blast often overlooked evidence of another tragedy, one attributable to the same corrosive forces: dozens of the dead and missing were Syrians, many of whom had escaped air raids, shelling, and snipers to make it to Beirut, where they hauled cargo on the docks for a few dollars per shift.

Lebanon, a country of about 5 million citizens, is now home to 1.5 million Syrians, by far more refugees per capita than any other country—roughly equivalent to all of Mexico resettling in the United States. But Syrians in Lebanon are not called “refugees,” with the rights and protections the term implies; they are instead referred to as “displaced,” or, even more euphemistically, as “guests.” Such nomenclature is rooted in Lebanon’s obsession with maintaining its “demographic balance,” which was established in 1943, after the French carved the country out of Syria and divided power between the area’s eighteen recognized religious communities. Lebanon’s president must always be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of parliament a Shiite Muslim. In a sense, the system worked too well: it paralyzed centralized decision-making, reducing much of Lebanese political life to squabbles between elite families for influence and kickbacks. The balancing act is so delicate that the government has not conducted a census for nearly a century.

So when hundreds of thousands of Syrians—most of them Sunnis—started pouring over the border in 2012, many saw them as a threat to the established order. In response, the government tried to ignore the refugees, marginalize them, and, as a 2014 policy paper put it, push them to return “by all possible means.” To this end, Lebanon took a position unique among the world’s major refugee host countries: It refused to establish camps, fearing they would encourage refugees to stay or, worse, provide a structure in which Syrians could organize and push for political and economic integration. Both Turkey and Jordan, despite many problems of their own, set up camps housing tens of thousands of displaced Syrians. In Jordan, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees manages the camps, while in Turkey the government runs them with substantial UN support. In Lebanon, no one was in charge.

Rather than take responsibility for the country’s political dysfunction, the government increasingly scapegoated refugees—and many Lebanese readily bought into the fearmongering. Syrians were portrayed as a human “time bomb,” threatening to upend Lebanon’s security. Graffiti appeared around Beirut reading beware your enemy: the syrian is your enemy. Pundits blamed Syrians for crowded schools, deteriorating roads, power outages, joblessness, and pollution, all of which predated the arrival of refugees. Writing in 2014, Karim El Mufti, a political science professor at Beirut’s Saint Joseph University, described Lebanon’s approach to Syrian refugees as a “disastrous policy of no policy.”

The consequences of Lebanon’s no-policy policy are most evident in the Bekaa Valley, a fertile strip of flatlands that lies across the mountains from Beirut. Sharing more than a hundred miles of border with Syria, the valley has become the center of the crisis, housing some 40 percent of Lebanon’s refugee population. Lacking formal camps, groups of Syrians were forced to jury-rig clusters of tarp-and-stick tents wherever they could, following the blind logic of desperation, only to be batted from place to place by security officials, rapacious landlords, and hostile locals. Ranging from a few dozen to more than two thousand residents, these camps—or “informal tented settlements,” as the United Nations calls them—proliferated along roadsides and in fields, on hillsides and city outskirts. Their arrival marked one of the largest demographic transformations in the modern history of the Middle East. Like Lebanon’s other problems, the camps were treated as temporary, even as an entire generation grew up within them—the population of a small nation living in catastrophic limbo: laboring, suffering, rejoicing, giving birth, and dying.

One evening last summer, I rode along with Omar Abdullah, a young Syrian aid worker, as he distributed goods—things like water tanks, gravel, and lampposts—to makeshift camps in the Bekaa. Almost anywhere else, UN agencies would have coordinated and standardized this process, but in Lebanon, the task was often left to tiny nonprofits like Sawa, where Abdullah worked, to contact and negotiate with hundreds of individual camp leaders. For more than six years, Abdullah had been traveling from camp to camp, often at his own expense. Short and slim, with a heavy beard and a warm if infrequent smile, he was always working or thinking about work. His childhood home in Syria, Zabadani, was only six miles east, over the mountains, but he had not visited in nearly a decade. At twenty-eight, he was a ripe age for military conscription. For him, as for the refugees he served, going back was out of the question.

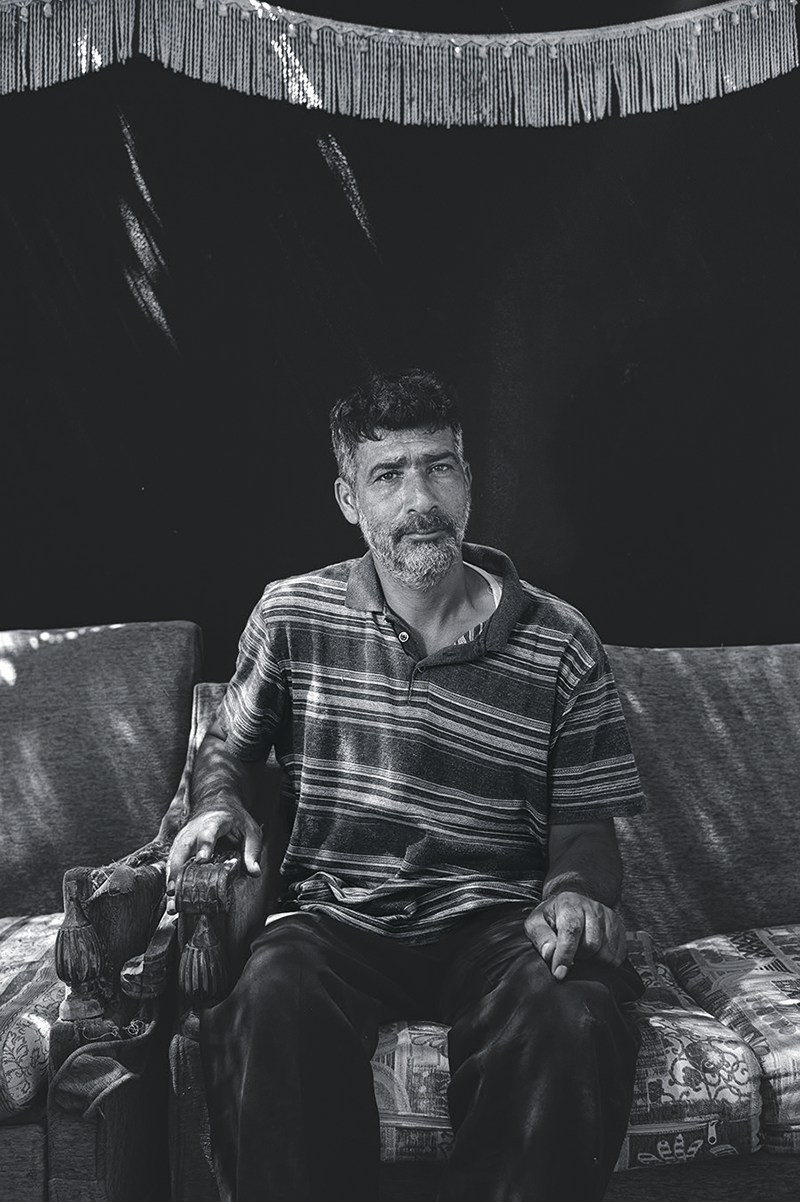

As the sky darkened, we drove through fields of lettuce and cilantro, then past convenience stores, bakeries, and pharmacies, where men and women sat outside, smoking and playing Arabic pop music on their phones. We exited the highway and pulled up to a large camp where white tents, streaked with dust and weighted down with old tires and concrete blocks, stood in rows along gravel pathways. Rusted satellite dishes and small chimneys protruded from the roofs; plastic chairs and old cushions adorned modest patios. A tall man with a short salt-and-pepper beard and sun-browned skin stood waiting to greet us, a pack of cigarettes tucked into the chest pocket of his short-sleeved plaid shirt.

This was Taleb al-Bizazi, the shawish, or camp leader. Shawishes are the primary brokers between the demimonde of refugees and the aid workers, municipal officials, employers, security agents, and journalists who interact with them. They allow the Lebanese government to monitor, track, and control refugees without issuing visas or granting rights, and over the years they have evolved into something like an underworld political class, an informal cadre governing the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. Whether a camp receives aid, whether farmers hire its residents, and how many security raids it endures all depend on the skill, savvy, and connections of its shawish. Most camp leaders saw the benefit of courting aid workers like Abdullah, who could help them work the system to their “minimum disadvantage,” as the historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote of European peasantry. But if shawishes decided they didn’t want Abdullah around, there wasn’t much he could do.

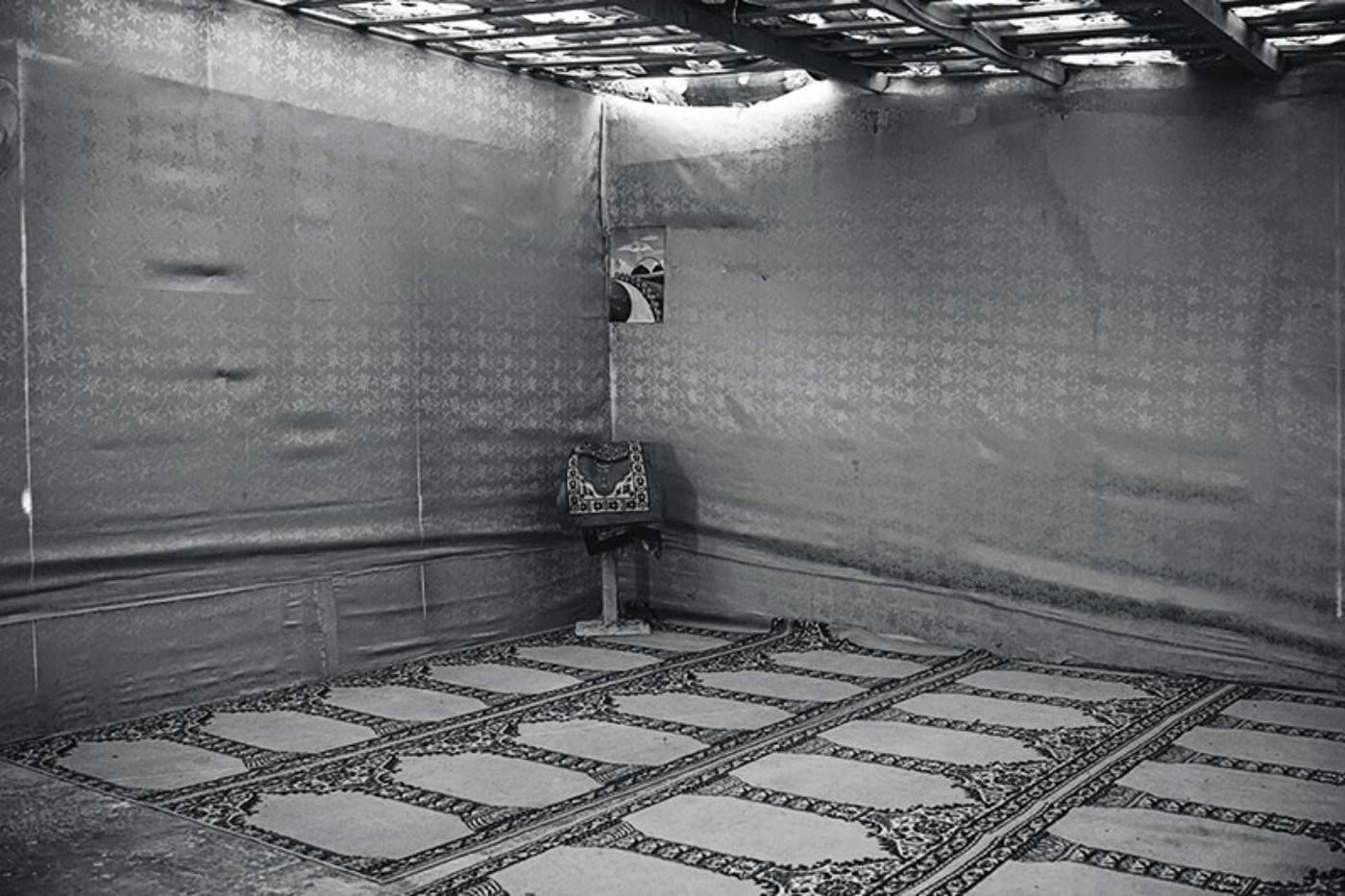

Abdullah had known al-Bizazi for nearly three years. They met after Lebanese soldiers evicted al-Bizazi and his flock from their original campsite for settling too close to a military base. The winter of 2016 was brutal, even by the unforgiving standards of the Bekaa, where temperatures often fall below zero and snowstorms and floods wreak constant havoc. Many Syrians had frozen to death across the valley. Since the camps did not have addresses and did not appear on maps, there was often no point in calling an ambulance for someone who was dying; the driver wouldn’t be able to find them, and few people could afford the hospital bill. When Abdullah came across al-Bizazi’s camp, its residents were freezing, up to their ankles in mud and floodwater. Sawa helped them find a new plot, negotiate the rent with a local landowner, and transport their few possessions. Gradually, al-Bizazi began rebuilding: he set up water tanks, lampposts, flower gardens, a small school, a courtyard where children could play soccer, and a mosque built from old billboards. With about seven hundred residents, the camp had begun to feel like a small village.

“Habibi,” al-Bizazi said, leaning in to kiss Abdullah’s cheeks. “Come in, come in.” They hooked their arms over each other’s shoulders and crunched down the main path through the camp, past people stretched out on the ground smoking hookah. The day’s heat had just broken, and the camp buzzed with evening activity; men chatted in one tent, a barber trimmed hair in another. Al-Bizazi led Abdullah into a wooden shack, invited him to sit on a shredded sofa with Styrofoam blocks for cushions, and offered him coffee. A single fluorescent bulb hung from the ceiling, casting a bluish glow over the dirt and illuminating swarms of tiny flies.

Taleb al-Bizazi

Abdullah produced a stack of documents—forms for itemizing assistance requests—and handed them to al-Bizazi and his deputy, Alaa Turan, a stout man with a long beard who had just received a haircut. Turan scratched at the freshly shaven back of his head as the three men lit cigarettes and got to work. Abdullah began flipping through papers, showing the men how to fill in the camp’s information and budget for requested items. Turan listened, asking for clarification here and there, and then started filling in the boxes.

Abdullah watched silently. He’d been at this for days already, ushering men of varying integrity, temperament, and competence through the process. Few were accustomed to the complex administrative tasks that aid bureaucracy often demanded. Al-Bizazi had been a plasterer in Syria, Turan a painter. For ten minutes or so, Abdullah kept still, but then his nerves betrayed him. He sprang up, ran a hand through his hair, and lit a cigarette as he paced around the hut.

Al-Bizazi and Turan looked up. “What’s with you?” al-Bizazi said.

“Nothing,” Abdullah said. “It’s just, I have to do this with fifteen camps. There’s more after you.” The two men stared for a moment, and then squinted back at the paper. Abdullah looked out at the sunset. Then he finished his cigarette, sat down, grabbed a scrap of cardboard from a nearby heap, and positioned it on his lap as a desk. “Give me that,” he said, taking the paper from Turan. “Here: windows, doors, chairs. . . . ” With Abdullah’s help, the paperwork was complete in about forty minutes. Abdullah sat back, his shoulders relaxing. One of al-Bizazi’s young sons brought a tray of Armenian cucumbers, and the men smoked until it was time for us to go. We walked back to the gate and said our goodbyes, the green disks of minaret lights visible against the distant, silhouetted mountains.

Back on the road, Abdullah told me it had taken years for him to earn al-Bizazi’s trust. The first time they’d met, al-Bizazi had been so scared and embittered that he’d yelled at Abdullah: Why are we being ignored? Why do we have to suffer alone? “Little by little, we got to know each other, and our relationship improved,” he said. “At first, the situation was terrible. No one was helping.” Abdullah was often stuck in situations like these, trying to manage the frustrations of people caught in a system over which none of them had any control. Yet his temper rarely slipped. Although his own disappointments were myriad, he knew that getting angry wouldn’t do anyone much good.

I remarked that there must be a lot of camps still out there as isolated as al-Bizazi’s had once been before he’d found it—invisible to aid agencies, suffering quietly, alone.

“Yeah,” Abdullah said. “A lot of camps.”

Lebanon’s shawish system began as a perverse outgrowth of its no-policy policy. At first, aid groups attempted to set up self-governing committees in the camps, but Lebanese authorities dismantled them and demanded that shawishes be appointed instead. Even as the state came to rely on the shawishes for control—and as a generation came of age under the system, knowing no other way of life—they remained unrecognized. There is no ministry to oversee or count them, no syndicate to coordinate their efforts or press collective demands. Those chosen as shawishes were often respected elders or chiefs of displaced tribes, but sometimes they were simply the most literate person at a particular camp. Lebanese security officers often didn’t care who the shawish was as long as discipline was maintained, which allowed for the rise of some unconventional figures, such as Amshe al-Hussein, a female shawish who ran a camp inside the concrete husk of a former chicken processing plant. She was thirty-five, had no formal education, and had come to Lebanon years before the war, working with her husband in the fields of the Bekaa. When refugees started arriving, the couple decided to rent a plot and set up a camp. It grew to house nearly five hundred people, making it one of the larger settlements in the area.

The sky was a cloudless blue when I set out to meet al-Hussein, driving through an industrial area of warehouses and scrapyards and onto the rutted dirt roads of the Bekaa, where the air smelled of manure. I stopped at a roadside shop to ask directions, and the attendant, an old man in a galabia, gestured toward a road that led past a half-finished concrete building, its top floor bristling with rebar. I parked by a store built from breeze-blocks and corrugated metal, and a man emerged to ask what I wanted. I told him I was there to see al-Hussein and he ducked inside, reappearing a few minutes later to wave me into the store, which was much larger than most I’d seen in the area, its shelves stocked with rice, cooking oil, juice, cigarettes, and other staples. Three men in red keffiyehs and brown galabias sat in a circle between two TV screens, one blaring a Saudi-owned news channel and the other showing a split screen of eight security-camera feeds, one of which was trained on my car. Before I could ask why they’d set up the surveillance system, al-Hussein appeared. She wore a bright-blue feather-print dress, and she held two smartphones in one hand and a pack of Winchesters in the other. As she entered the room, she eyed me like a pawnshop owner appraising a potential purchase.

I followed her into the first of the three buildings that made up the old factory compound, which had been converted into small living quarters. Most of the rooms contained a heating stove and the same basic set of drab blankets and cushions, but splashes of personality adorned the walls: a gilded Qur’anic verse, a red teddy bear, a patterned curtain. As we moved between rooms, the aroma of frying garlic and onions occasionally overpowered the scent of mildew and stagnant water. “It’s a good spot, but the roof leaks,” she said. She stopped and pointed to a section of corrugated metal with cracks between the panels, allowing rain to seep in. The potential for disaster in winter haunted her. Al-Hussein told me that they were supposed to receive assistance on this front from an aid group, but in her three years at the camp, it had never arrived. “Some people got aluminum roofs, but our turn never came.”

Al-Hussein was at pains to distinguish herself from shawishes who exploit the people living in their camps. At a neighboring settlement, she claimed, a shawish named Ahmed ruled like a “tyrant,” jacking up rents, expelling those who couldn’t pay, and running illicit operations like forgery. “If it wasn’t for fear, people would eat each other alive in the streets,” she said. “There are so many dirty people, so much haram.” With unscrupulous neighbors like hers, there was always the risk of thieves or a raid by security forces chasing down local criminals. Faced with these pressures, her camp had to fend for itself as best it could. “Why do you think I had the cameras installed? Some shawishes are like the Angel of Death.”

She was barely exaggerating. The course of a Syrian refugee’s life could be determined by the whims of a shawish. Some shawishes made sacrifices to keep their camps together; others worked the system to their personal benefit. Some shawishes made decisions by committee, others by fiat. I had heard about a former Syrian army officer who became a shawish and collected the entire camp’s income to redistribute as he saw fit. The line between salvation and exploitation was thin. In many camps, residents depended on the shawish to access basic services such as health care or water. Often, the shawish provided loans for tent materials, travel, and basic amenities. Not far from al-Hussein’s camp, I met a shawish named Hozaifa Ibrahim who described his camp the way some might describe a small business. When I visited, he was arranging old tires planted with wildflowers on a small patio. He listed the “services” he provided, such as steering residents clear of employers known for not paying. But I later learned from an aid worker that Ibrahim had prevented the camp’s children from going to school so that they could work in the fields.

Amshe al-Hussein

Ensuring that a camp remained free of weapons, drugs, and terrorist activity was central to the role of any shawish. Lebanese security forces could raid the camps, harass and arrest residents, and remove a shawish if the government’s standard of order was not met. The stakes were raised in 2018, when the General Security Directorate, Lebanon’s intelligence agency, which has ties to Hezbollah and Syrian authorities, made a deal with Bashar al-Assad to send people back to Syria under a “voluntary return” program. More than twenty thousand refugees have since been bused out of Lebanon. Hundreds more, including army defectors, have been deported individually, in an apparent violation of non-refoulement—the right not to be sent to a country where you face persecution—which underpins international refugee law.

To keep her camp safe, al-Hussein maintained close ties with local security officers; she understood them as the best protection against raids and deportations. “If you’re under the law, no one can touch you,” she told me. She scrolled through her WhatsApp exchanges with local officers, replete with thumbs-up emojis. “If they need anything, they call me. If they have a problem with anyone, they call me,” she said.

Al-Hussein led me back through the store, where the news was broadcasting footage of fighting in Iraq. She bid me goodbye, and then looked up at the screen with the security feeds. She picked up one of her phones. “Fadel,” she said. “What’s that car that just pulled up?” When I left, she was still watching the screen.

Syrian children harvest onions in the Bekaa Valley

In the months after I left the Bekaa, Lebanon’s precarious balance began to teeter, and then gave way. Since 1997, the Lebanese pound had been pegged to the U.S. dollar, which helped the middle class by effectively subsidizing imports and propping up the value of remittances from the vast diaspora. But the system, which one economist has described as a “regulated Ponzi scheme,” required an influx of dollars in order to sustain itself, and last October the reserves started running out. ATMs stopped dispensing U.S. dollars; banks limited withdrawals; and the Lebanese pound lost 80 percent of its value in nine months, shredding Lebanese citizens’ bank deposits, not to mention the already meager financial aid on which many refugees subsisted. In April, a Syrian man in his fifties, driven to despair, set himself on fire in a field near the camp where he lived.

Antigovernment protests broke out across the country. Power outages, which were already a regular feature of life in Lebanon, grew longer and more frequent as supplies of imported fuel dwindled. The trash crisis, which had never been fully resolved, intensified when local landfills that were being used as stopgap measures reached capacity. Garbage choked Beirut’s streets and toxic runoff streamed into the Mediterranean. Petty crime surged, food shortages became common, and poverty spread.

In response, politicians continued to scapegoat Syrian refugees. The Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), a Maronite party founded by Aoun, began popularizing the phrase “Lebanon can’t bear it” in reference to the Syrian presence. Labor and visa restrictions on Syrians—who were already banned from working outside of agriculture, construction, or sanitation—were tightened further, and the FPM’s television channel proudly showed bands of young men harassing Syrian workers. Gebran Bassil, the leader of the FPM and Aoun’s son-in-law, went so far as to praise the “genetic” qualities of the Lebanese in a Twitter rant against foreign labor.

Even before Lebanon’s financial crisis and the pandemic, some two thirds of refugee families lived on less than three dollars a day. Children were often put to work or married off to make ends meet. Fewer than half of the four hundred thousand school-age Syrians in Lebanon were enrolled in school. This spring, conditions in the Bekaa deteriorated further as anti-Syrian propaganda caused tensions to mount between refugees and their Lebanese neighbors. In one town near the valley’s northern tip, refugees hurled rocks at a fire truck when it showed up hours after a blaze. The next day, local Lebanese attacked the camp and pushed its residents off the land, shouting, “You are sullying our soil!” The country’s top security council ordered the removal of all “semipermanent” structures, many of which were simply humble assemblages of breeze-blocks and corrugated metal. They claimed this was necessary to enforce local building codes, but the only practical effect was to humiliate and endanger those found to be in violation of the policy. I met one man who had been forced to dismantle his shack in a Bekaa camp, leaving him with only a single painted wall. He seemed almost embarrassed to be so affected by the loss of something so modest. “You live in a room for four or five years, you raise your children there, and then suddenly you have to go and you see it destroyed right in front of you,” he told me.

When the port exploded this summer, it seemed at first to be one crisis that the politicians could not use the refugees to exploit. The day after the blast, France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, toured the hardest-hit areas and was swarmed by people crying for help. Macron condemned Lebanon’s political order as corrupt, while saying nothing about France’s role in establishing it. He later promised that the Lebanese government would have to agree to a program of antigraft measures and an audit of the central bank or face sanctions from the international community.

Later that afternoon, Macron met with Bassil. In the months before the explosion, Bassil had become a prime target of antigovernment protesters, who saw him as a symbol of the corruption, nepotism, and incompetence that was strangling the country. He had held several high-level positions, including energy minister and foreign minister, despite having no clear qualifications for them. Bassil warned Macron that if Lebanon “fragmented,” the refugees it had “generously” hosted might decide to continue on “toward you”—effectively threatening to turn the Riviera into a new Bekaa. Pressed on his comments by a CNN interviewer the next day, Bassil grinned and shook his head. He said he was merely telling “our friends in Europe” that they should not allow the current political order to collapse. Lebanon, he insisted, shouting as the interviewer wrapped up the call, was “the most humanitarian country on earth.”

A Syrian sanitation worker in Beirut

One night last summer, before I left the Bekaa, I spent an evening with Abdullah at his apartment, a fluorescent-lit two-bedroom he shared with another aid worker in Bar Elias, a poor, dusty town of concrete low-rises in the center of the valley. We sat on cushions on the floor; Abdullah smoked cigarettes and poured us maté, a heavily caffeinated South American drink that had become popular in the region. He spent many evenings this way—local entertainment was scarce, and he didn’t have much spare cash to enjoy it anyway. We’d just returned from a camp, and the next morning he would set out again, visiting more settlements, coordinating more deliveries, helping more shawishes take care of their charges. The work wouldn’t stop unless something fundamentally changed, either in Lebanon or in Syria or in the global configurations of power that maintained the status quo. For the moment, that didn’t seem likely.

As we sat, Abdullah described how he’d watched the situation in the Bekaa slowly come into existence. Unable to square the circle of “demographic balance” in an age of mass migration, the Lebanese had allowed the Bekaa to fall into a state of limbo, at once outside the law and unofficially sanctioned by it—something the political philosopher Giorgio Agamben would call a “state of exception.” Writing last year, Nora Stel, a professor of conflict studies in the Netherlands, argued that while Lebanese authorities portrayed the chaos in the Bekaa as a consequence of an unmanageable crisis, the creation of “institutionalized arbitrariness” also gave authorities the power to “discipline, pacify, and control” refugees by keeping them locked in that permanent state.

Lebanon is not unique in this approach. In an age when more than 270 million people live outside their countries of citizenship, nations have increasingly relied on a state of exception to maintain the status quo. The packed Rohingya settlements in Bangladesh, the detention centers in Libya, and the privately run camps along the U.S.-Mexico border all exist in a parallel world of informality and ambiguity. As I listened to Abdullah recount the turmoil in the Bekaa, I thought of something my landlord’s brother told me after returning to Beirut from a vacation in Burgundy, where he’d been talking to French friends about the situation in the Middle East. He said he had pointed out the roses that vintners plant near their grapes to detect diseases before they reach the vines. “We are your white roses,” he told them. “And we are very sick. And one day, your wine will be sour.”

As Abdullah saw it, an entire generation of Syrians was growing up in what amounted to miniature autocracies. “We’re putting the wrong ideas into people’s heads with this system,” he said. “If I’m in the camps, and I see that the decision is in the hands of the shawish, and that he gets his power from the security agencies, the municipality, and so on, then I don’t have a chance to participate, not even to offer my opinion.” He paused. “We’re not benefiting from the experience.” The Syrian displacement was a cataclysm—but it could also have offered a break from an authoritarian system, a chance to try out new, more egalitarian ways of living. The camps could have held elections, for instance, or formed small councils. One day, those structures could have been implemented in Syria. The failure to seize this opportunity to experiment with democratic forms was to him the real tragedy. “Lebanon is a place of refuge, yes,” Abdullah said. “But it could also be a place to establish something for the future. That’s what we wish we could do.”