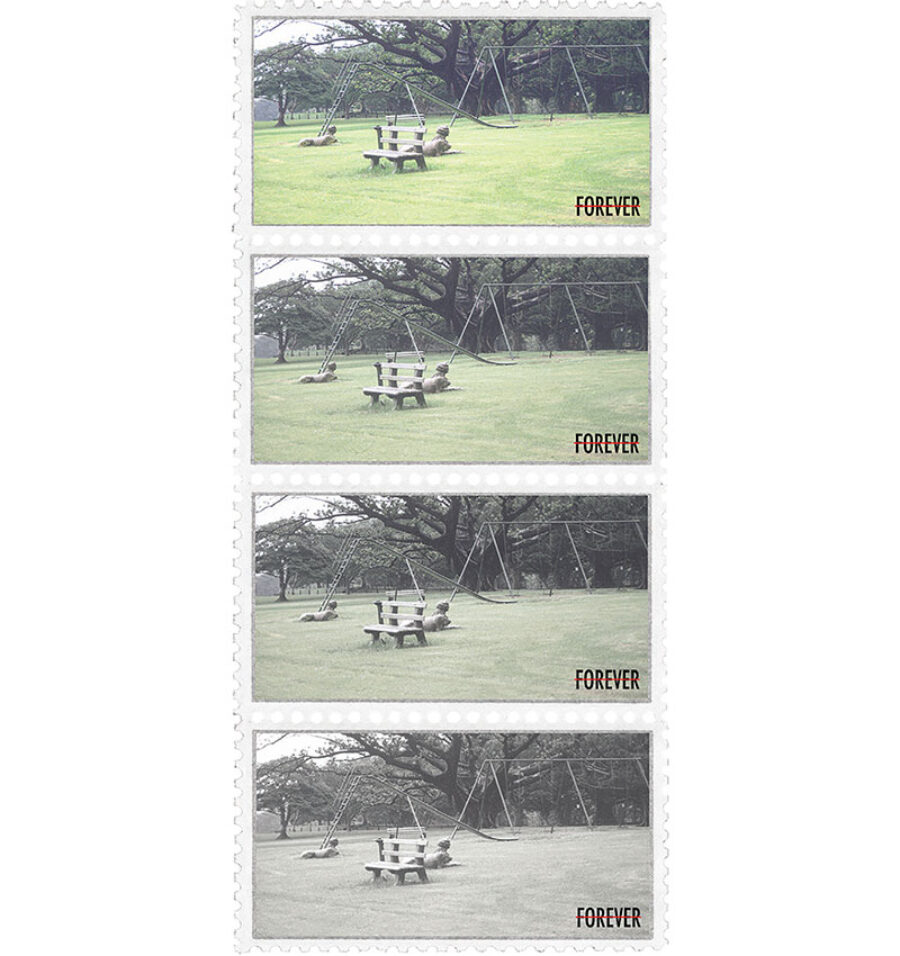

Artwork by Barbara Bloom. Courtesy the artist. This pairing of text and image is part of an ongoing collaboration.

The Grove

Then she suggested I make a list of all the things I’m grateful for. No entry is too small or mundane: access to clean water, fast internet, the weeping habit of the flowering cherry. And you can be grateful for what you don’t have, she explained, lice or color blindness. A friend in Bellevue. A daughter in pain. We were sitting on a bench in Green-Wood Cemetery, sitting as far away from each other as possible. It was late April and I could just pick out the song of nearby warblers from the distant, constant sirens. But it’s important you make the list by hand, there’s something crucial about the physical contact with the paper, the embodied act of mark-making, she explained. And each sentence must start the same way—“I’m grateful for”—the repetition helps form a groove in your consciousness so that, when idle, your mind will gravitate toward an awareness of its blessings instead of the darker ruminations you’re describing. Males sing a slow, soft trill. It lasts about three seconds. I suggest making the list at the same time each day, I make mine in the morning, but I have clients who make them at night, right before bed, just ten or fifteen minutes of writing, set a timer on your phone. Whereas the ovenbird, named for its domed nest, sings: Teacher, teacher, teacher. I was trying to locate the rage in my body, to greet the rage so it would dissipate, trying not to ask out loud: Is that what I am to you, another client? Instead I asked: Is the list aspirational, can I list things I want to feel grateful for, should feel grateful for, or does the gratitude, at the time of writing, need to be an accomplished fact, available to feeling? She looked at me to ascertain whether I was being serious or merely difficult, but I did not turn my head to meet her gaze, didn’t want to see the patient smile, the diastema. A gust of wind provoked a rain of pale white blossoms onto the stone path, but the tree’s stock of blossoms did not appear diminished. The rage, which I’d experienced as lodged in my temples and the back of my neck, turned now to unalloyed sorrow, which lives in my chest. Aspirational is fine, she said. Aspirational is great. The word “aspirational” brought out her Argentine accent. She coughed twice, and I imagined airborne droplets traveling from her mouth to mine, or entering my body through my eyes, pathways to the soul, and I welcomed that, was grateful for it, wondered whether I would get an erection and, if so, whether I would be able to hide it from her if she stood suddenly and wanted to continue birding. My brother is color-blind, I said. Nobody had any idea until we drove to St. Louis one weekend and visited this place called the Magic House, a kind of science center for kids. I was seven and he was ten. There was a room there, almost a gallery, where they displayed a variety of those “digit tests”—circles formed by dots of different sizes. Inside the pattern dots of a distinct color form a number invisible to those with a particular color deficiency. My brother kept saying he couldn’t see anything in the circles and while at first my parents thought he was joking, I could tell that something suddenly clicked for them. How many times had they asked him for the red marker and been handed the green one. How many times had the otherwise perspicacious kid failed to circle the yellow bird on the math worksheet. Maybe this is why for as long as I’ve been looking at paintings I always feel like a deficiency might be revealed, aesthetic experience is tinged with that anxiety for me, the way the blossoms are tinged with pink. But I also remember being really jealous of my brother, his specialness, his difference, maybe because my parents, guilty for having failed to diagnose their son, subtly favored him for a few months, or maybe because of what happened in one of the next rooms at the Magic House. There was a wall that consisted almost entirely of safes with combination locks. This room was crowded with people trying random combinations, trying to open one of the safes. On the wall was a list of the probabilities of arriving at the right permutation for the respective locks. The point was it was nearly impossible. And yet this was one of the most popular rooms in the Magic House. Certainly my brother and I were instantly mesmerized, trying random numbers again and again, refusing to give any other kid a chance at our safe, even though the wall text said the safes were empty. I don’t know how long we spent in the safe room, which had the frenetic feel of a video-game arcade, or people playing the slots, that kind of mania, but at a certain point I heard, I remember hearing, my brother’s safe make a satisfying click. Everyone gasped, fell silent, and watched as the small, heavy door swung open. You’re making this up, she said. And out of the darkness of the safe burst forth seven parrot finches with bright-green bodies and red heads, birds I thought my brother couldn’t see, believing as I did that being color-blind meant you couldn’t perceive the colored object, not just an aspect of its surface. If my brother were here today, he would see stone paths making their way through empty space, none of this vibrating green, and he would hear all the notes of birdsong at once. I turned toward her suddenly, involuntarily, and said, my anger unmistakable: I’m grateful for color blindness, the missing cones, the hidden figure. I’m grateful you and your family are moving to Buenos Aires for a while; I’m sure you’ll never want for clients. She looked at me with a vaguely erotic pity, took a sip of chamomile tea from her paper cup, a cup she’d brought from home, not a café, cafés hadn’t reopened yet, but which seemed store-bought, as if she had access to an open city. A couple of years ago, she began, Luna had lice. She’d been itching for a while, but it wasn’t until the school sent out an email reporting lice in the kindergarten classroom that it occurred to me to check. When I went through her masses of curly black hair with a steel comb and a flashlight, I was shocked: I not only found lots of nits, dots of different sizes, but plenty of live insects moving around her hair. I felt guilt, a mother is a machine for making guilt. I tried to comb them out and bought that medicated shampoo. She slept with a plastic shower cap, which was very cute. A couple of days later we got another email about the ongoing lice situation from the “class parent,” who said that many of the moms also now had lice, that’s what we get from all that cuddling (smiley-face emojis, exclamation points). But I didn’t have any lice, even though Luna’s scalp was an open city, and now I wondered if this meant we weren’t cuddling sufficiently, that I wasn’t being affectionate enough physically, which sounds crazy when I say it, given how often we’re entangled, but at the time we were trying to set some firm limits about her coming into our bed at night. I was a bad mother for failing to notice her itching, the lice, a worse mother for having failed to contract lice myself, for having banned her from our bed. This was all overdetermined for me because lice—for my grandparents and so for my parents—meant the camps. Had I abandoned my family in Argentina? Certainly I’d abandoned Judaism; I was a failed daughter failing my daughter. Don’t make a joke about psychoanalysis, Ben—I’d opened my mouth to speak—I’m not making an argument, I’m describing a feeling. The shampoo didn’t work, there were more nits than I could remove, so I googled what to do: it turns out the expert lice pickers in New York are all Orthodox Jews, mainly in Midwood, it’s fascinating, I can send you the Times article, and so I just chose this woman who had the best Yelp reviews. That night I got into bed with Luna, didn’t even wait for her to come to my room, and we slept cheek to cheek. You’re making this up, I said. I wanted the lice to connect me to my predecessors and my progeny. The next day, when this young woman—long black dress, her hair covered with a scarf—picked a louse from my hair, held it to the light, I was so happy, tears started in my eyes. The woman thought I was ashamed of myself and tried to comfort me. You have so many things to be grateful for, she said. Your beautiful daughter, your home, running water, that lice can be killed on the Sabbath, even though it’s a day of rest, an exception issuing from the ancient rabbis’ belief that lice are spontaneously created from dust. She took a sip of her tea, which must have been cold. Something stirred in the towering oak behind us, maybe a raccoon raiding a nest for eggs. I looked up and saw a plane moving slowly across the sky, a ghost flight, an empty or nearly empty plane following an established route so the carrier can retain its slots at airports; the repetition forms a groove. The white streaks on the warbler’s back are tinged with olive, the darker ruminations tinged with gold.