Illustrations by Delcan & Company

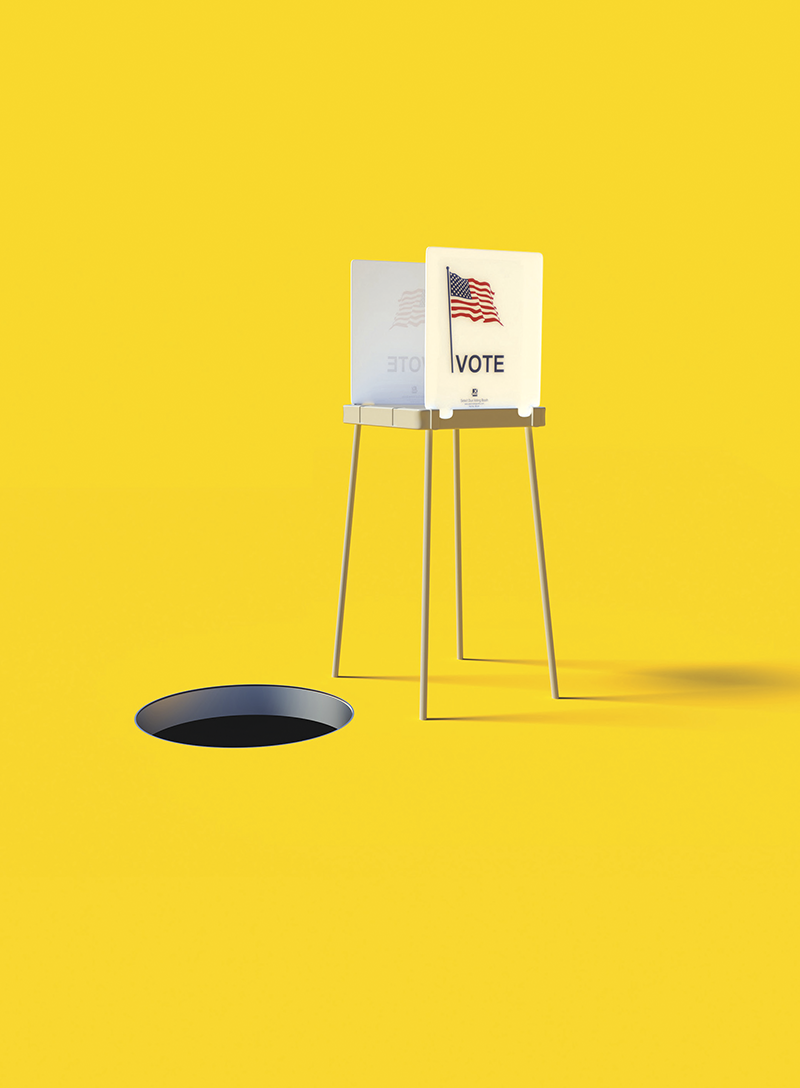

On Tuesday, November 3, Americans will cast their votes for president for the fifty-ninth time in our nation’s history. Republican efforts at voter suppression have long undermined the notion of free and fair elections, but Donald Trump has diminished the integrity of our electoral system even more profoundly—by sabotaging the Postal Service, disregarding the Hatch Act, and leveling false charges of voter fraud, while doing nothing to prevent interference by foreign governments. These threats demand urgent action on the part of political leaders, but they also raise difficult questions about what it means to be a citizen in a democracy, particularly one that is failing to live up to its ideals. Do we have a moral obligation to vote even if the electoral system is corrupt or unfair? Who should be allowed to vote, and by what methods? What does it mean for a government to be representative?

In July, Harper’s Magazine brought together a diverse group of scholars and journalists on Zoom to discuss the ethics, mechanics, and implications of voting, and to think through the role of citizens in a democracy at risk. The conversation was moderated by Harper’s editor Christopher Beha.

participants

Danielle Allen is the James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard University, the director of Harvard’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, and the author of Our Declaration.

Jamelle Bouie is a columnist for the New York Times and a political analyst for CBS News.

Jason Brennan is the Flanagan Family Professor of Strategy, Economics, Ethics, and Public Policy at Georgetown University and the author of Against Democracy.

Sarah Smarsh is a journalist, a recent Joan Shorenstein Fellow at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, and the author of Heartland.

Astra Taylor is a documentary filmmaker, writer, and political organizer. She is the director of What Is Democracy?

i. the voting imperative

christopher beha: I want to talk about the specifics of America’s democratic situation, but I also want to address some abstract, philosophical questions about voting. Let’s begin at that level: As a general matter, do you all think that citizens in a democracy have an imperative to vote?

jason brennan: I don’t think so, but most Americans do. Even though not everyone votes, surveys show that about 96 percent of Americans say they think there’s a duty to vote. Now, whether they really believe that or not is a good question. But when you look at the specific arguments people give in favor of an obligation to vote, they’re usually very general: You should do something that exhibits civic virtue. You should do something that contributes to the welfare of your fellow citizens. You should do something that repays any debt to society that you might have.

These arguments suffer from what you might call a particularity problem. All they show is that voting may be one of many different ways—some of them much more effective—to discharge the underlying obligation in question. A typical auto mechanic does a lot more for society by fixing cars than he or she does by voting. That’s not to denigrate voting necessarily; they’re just fundamentally different contributions. When we’re voting, we have a very small chance of making a difference. We could spend the time it takes to vote doing something else that contributes to other people’s welfare, or fulfills a duty, or repays a debt to society.

I tend to think of voting as similar to farming. It’s important that enough people grow wheat. It doesn’t follow that we all have to be wheat farmers. It’s important that enough people, and a variety of people, vote. It doesn’t follow that every single person has to vote.

danielle allen: The thing that Jason misses is the incredibly important informational value of voting. What I mean is that until people vote, we do not know what the opinion of the populace is. Public opinion surveys are not a replacement for this information, which is something you can determine only with maximum voter participation. This is a completely different question from whether or not a vote makes a decisive difference in any particular election, and it’s one from which I think you can derive an obligation to vote.

astra taylor: When I was doing Q&As for my film What Is Democracy?, I encountered a lot of sanctimony about voting. There would inevitably be an older white gentleman who would stand up and say, “I can’t believe that people in this country don’t even vote.” He never seemed to wonder, Why don’t they? Why do they feel disconnected? Why do they feel cynical? When I asked people about this in interviews, people would tell me that it was too difficult to vote, or that their vote didn’t count—which is often objectively true, depending on where you live and which election you’re voting in. People aren’t optimistic that anything will really change, an intuition backed up by research showing that regular voters have very little influence over policy. In my opinion, saying “Oh, there’s a moral imperative. People have died for this right, and therefore you have to vote” doesn’t do justice to all of the things that are weighing on the politically disengaged.

sarah smarsh: I was raised around people who didn’t vote. I was a child in the Eighties and a teenager in the Nineties—Reagan through Clinton. My mother always voted in presidential elections, but most of my rural, working-class community was not engaged politically. It wasn’t quite apathy, that’s not the right word for it. They didn’t neglect to vote because they didn’t care, or because they were lazy, or because they weren’t intelligent, bright people with ideas and the desire for a better country. Rather, they lived far away from a polling place and lacked the time and energy required to be politically informed. We were working the summer wheat harvest, dawn to dusk, when other Americans were attending campaign events or civic meetings. While others were voting, we were working. Similarly, millions of America’s laborers are moving the gears of society while the chattering classes debate politics on Twitter.

There’s no complete excuse for not paying attention. But I want to echo Astra’s point that there are many people for whom nonvoting is neither a political stance nor a symptom of moral failure. It’s just the only plausible outcome of the limitations of their lives.

The real moral imperative—one we could surely all agree on—is that those who have the power and privilege to construct election systems must do so in a way that makes them accessible, equitable, fair, and democratic. We certainly don’t have that at the moment.

jamelle bouie: I don’t know if there’s an obligation to vote. But to echo Sarah’s point, the question itself might sidestep other, more critical questions: Do people have the material security or the access to feel that they can actually participate? Are people empowered in their lives in such a way that they can make a connection between politics and voting?

The impulse of the “framers”—not a term that I love, but one that I’ll use—to restrict voting to landowning white men reflected their prejudice, but it also reflected their sense that you could only participate in republican society if you had some sort of material stake. Once you had some kind of security and responsibility to others, then you had a base from which you could participate in republican government.

I actually don’t think that that insight is wrong. If we live in a society of universal suffrage, where everyone is a political equal—at least on paper—then that imposes obligations on those who control the system to allow people who want to participate to do so. I’m not sure whether there’s a moral obligation to vote, but I do think there’s a moral obligation to construct a society in which people feel empowered to participate in politics.

allen: In some sense, Sarah and Jamelle are both getting at the hard question—whether we have a functioning system. If it is a nonfunctional, fraudulent system, then there is no point in voting, and the ethically correct thing to do would be not to vote.

beha: Does anyone here think that our democracy’s problems run so deep that we have an obligation not to vote?

bouie: I tend to think of the health of our democracy and the health of our voting system as related but separate things. There are ways in which our democracy is still very healthy. We have a vibrant public sphere. Civil society is still pretty robust. There are plenty of pathways for ordinary people to get involved in politics. There’s still wide space for public protest, as we’ve seen.

Even the two-party system remains unusually porous—there are points of entry for people who want to seriously change the direction of either party, for good or ill. In that regard, I don’t think American democracy is necessarily in bad shape. In fact, I think it holds up well compared with other advanced democracies.

But there are plenty of problems when it comes to voting, most of which stem from the fact that the Constitution lacks an affirmative right to vote. That absence ends up opening the door to the kinds of burdens we see today: the lack of a uniform voting system, the lack of uniform voting rules, all kinds of electoral chicanery. So there’s still a lot we could do to make America’s voting system and elections fairer, more competitive, and more equal, even if our democracy is relatively strong overall.

brennan: The United States has the problem of having come first, and much of the Constitution is the result of speculation by early philosophers who didn’t have experience with democracy. For example, they thought that having a two-house system would function better than a unicameral one. They thought that federalism would perform differently. They thought that the first-past-the-post voting system would work differently. We’re a mediocre democracy, weighed down by archaic rules from an old constitution.

allen: I agree with Jason; it really does matter that our institutions were invented in the eighteenth century. It’s striking that young democracies seem to have been able to handle the coronavirus pandemic much better than older democracies. You could frame the question as one of populist democracies versus institutionalist democracies, or another way, but “young versus old” also works. Social rights were baked into the fundamental structure of these newer, twentieth-century democracies. But in our case, social rights were grafted onto a structure that was originally focused on political and civil rights. This system has lots of issues and requires correction, but I wouldn’t say it’s so dysfunctional that we would be obligated to refrain from voting.

ii. the moral obligation to be informed

beha: If we do agree to participate in the U.S. electoral system, whatever our qualms with it might be, I wonder whether there is then an obligation to be informed before voting? To make sure that one’s vote is coming from a sophisticated understanding of the stakes?

allen: The model of the “good citizen” has varied over the history of the country, and that of the “informed voter” in particular dates to the Progressive Era. Women promised to become informed in making the case that they deserved the right to vote, and we’ve had that model of the informed voter ever since.

But there’s also the model of the character-based, virtuous citizen. And the partisan, the loyalist. Then there’s the activist who’s a defender of rights. All of these models of citizenship are important and relevant.

For me, the question is not so much, Is there a duty to become an informed citizen? but, How do we provide opportunities for people to acquire information through positive experiences?

smarsh: A lack of information was, I think, one of the reasons my community was not highly engaged in politics at the local, state, or national level. As I mentioned, becoming informed often requires time and resources that millions of Americans don’t have. Even if you can find the time, the academic tone, erudite language, and abstract frameworks of political discourse might feel like a distant, inhospitable planet. If you were raised in an environment that for understandable reasons didn’t value voting—let alone informed voting—where do you even begin?

allen: In addition to food deserts, which we’re used to hearing about, we also have a whole slew of places that are news deserts. And the environment for media and information consumption where news is accessible tends to be pretty horrible. Both of these things require correction so that voters have a healthy environment for information consumption and processing.

brennan: A very low level of general information among voters has been a persistent finding among political scientists since they started studying voter behavior. And not only a low level of information, but a low level of political ideology. The majority of people are voting for reasons that have to do with identity, not ideology.

I think—and this is the commonly accepted view in political science and economics—that this is a result of perverse incentives. It’s just not worth voters’ time to know things, unless they’re interested in politics—unless it’s their hobby or job.

This is a built-in issue with mass democracy. The probability of a vote being decisive is very small—casting a vote is like playing the lottery. Democracy thereby incentivizes people to vote for reasons other than information, or political preferences—to form alliances with people, to get dating partners and friends, or just to emote. So, before we consider whether one has an obligation to be an informed voter, we have to ask, Why is it that we’ve created this structural barrier to becoming informed?

bouie: I’ve always been curious about what it means to be informed in the first place, because often we’re thinking about whether someone can describe policy platforms, or can say what the parties stand for—the kind of information we imagine to be the substance of electoral politics.

But there’s a different way of imagining political knowledge. During Reconstruction, Southern states passed new constitutions in order to rejoin the Union. And in states like South Carolina and Mississippi and Louisiana, many of the people crafting those constitutions were formerly enslaved people—people who were barely four or five years removed from bondage. Many of them could not read or write, and those who had educations didn’t necessarily have deep ones. Nonetheless, they were able to craft constitutions that, at least in South Carolina, ended up lasting until the beginning of Jim Crow.

By most standards, I don’t think you would say that these people were informed. But they had knowledge of themselves as political subjects. They understood themselves as citizens whose lives were shaped by politics, an understanding that demanded they be political participants. To the extent that people need to be informed, they may need to be informed in that way—not necessarily to have particular rote knowledge, but to understand themselves as democratic subjects.

taylor: Yeah, we think of the “informed voter” as someone who understands government, who knows about candidates and their platforms. I mean, I was born in Canada, and just claimed my American citizenship. This election is actually the first time I’ve been allowed to vote in this country. So am I an informed voter? I don’t know every single person who’s running for office down ballot. Yet that’s the sort of political knowledge experts tend to judge people by.

But there are other ways people can be informed, as Jamelle suggested—someone might have experienced firsthand how unfair and nonresponsive the American system can be. This is a critical perspective that many people in power, or who are hyper-partisan or hyper-political, lack.

bouie: And that kind of lived experience is something you can’t get from traditional education. It’s something you get from the kinds of mediating institutions that have largely been in decline in our society: churches, unions, various civic associations.

Those formerly enslaved people who played a role in drafting Reconstruction constitutions were often Union Army veterans, members of union leagues; they were very much enmeshed in the exact sorts of institutions that help people bridge the gap between politics and daily life, and help them to see the connection.

taylor: If we want a public that’s more enlightened—and that’s an incredibly problematic word—then we have to prioritize and invest in all sorts of things that go beyond voting. We need to invest in public education at every level, we need to strengthen the free press, we need mediating institutions, especially unions, to be more widespread and robust. But in the final hour, I’m far more concerned with the ignorance of the powerful than the ignorance of the people. It would be interesting to imagine a public sphere where we spend as much time worrying about that as we do the capabilities and capacities of ordinary voters.

brennan: One way to remedy some of the problems we’re describing here might be something called “enlightened preference voting.” It’s based on a statistical system that political scientists have used for thirty years or so to study what determines voter behavior. What they’ve found is that if you collect data on what voters want, what their demographic categories are, and what their level of political knowledge is, you can determine what a demographically identical public would have supported if it were fully informed.

My suggestion is that we experiment with using this as an actual political system. Let everybody vote. But when you vote, you tell us what you want, who you are, and what you know. Based on that data, you calculate what the public would have wanted if it had been fully informed. In effect, you’d be debiasing democracy, by statistically correcting for the fact that turnout does not reflect the population as a whole.

I’m not saying this is perfect. I’m not saying it’s a panacea. But it’s a method we’ve been using for research that can reliably estimate how a debiased public might vote. And that’s at least evidence in favor of thinking it’s a better choice than our current system.

beha: Anyone have thoughts about that?

smarsh: I understand the validity of what you’re describing for research purposes, but who gets to decide what it means to be “fully informed”? Moreover, if we were to apply that model to the real world, we would be putting our energy in the wrong direction—trying to correct for ignorance by tampering with numbers rather than seeking to increase the knowledge of an expansive electorate through education and outreach.

allen: Another way of putting Sarah’s point is that this proposed system mistakenly assumes that the process of converting public opinion into political decisions is a static one. It’s not; it’s dynamic. This is the constructive justification for democracy, that the processes of democracy generate knowledge and change opinions. The values that frame our decision-making are contested and fought over. It’s that dynamic element that we need, not the static, descriptive element that research gives us.

bouie: Right, democracy is as much about the doing as it is about gathering preferences. It ought to be dynamic, as Danielle said, and ought to be a way for a population to express and harness its creative energies toward politics. I’m instinctively suspicious of anything that would seem to circumvent that, even if Jason’s idea does make conceptual sense. Which it does.

It’s like preferring to shoot on film versus digital. I know that a digital sensor is going to capture more detail and dynamic range than a piece of film strip. But arguably photography is about the analog processes of developing and printing film just as much as it is about the final product.

iii. the myth of the popular vote

beha: It seems clear that many Americans don’t feel encouraged to vote, and that their experience of politics has often been one of unresponsiveness or unfairness. One uniquely American institution contributing to this sense is the Electoral College. For a long time, the idea that someone might lose the popular vote and win the election felt like an abstract, almost technical point. Now we’ve had it happen twice in a generation. When you enter the voting booth, you do so knowing that the person you vote for could win the popular vote and still lose the election.

If you’re willing to participate in a system like the Electoral College, are you then required to accept the outcome of the election? Or can one still say that the fact that the person who got the most votes did not win is fundamentally unjust?

taylor: There’s been a growing awareness among liberals that the Electoral College has this amazing potential to thwart the candidates that the majority of voters have cast ballots for. But there’s an equal and opposite awareness among young conservatives that having structures of minoritarian control is their path to victory.

The day after Donald Trump was elected, I was in North Carolina interviewing a group of College Republicans. And I was struck by just how aware these twenty-one- and twenty-two-year-olds were of the fact that their candidate had lost the popular vote, and how committed they were to defending the Electoral College. There was a real attachment to it, and to the idea that popular opinion or the popular vote is actually a bad thing. I mean, they spoke in the classic language of “averting mob rule” and described cities as liberal cesspools. They didn’t speak the language of democracy as Ronald Reagan might have when he invoked the Moral Majority, for instance.

brennan: We have to be careful about talking about this thing called the popular vote. When we refer to the popular vote, we’re imagining that politicians campaigned for the popular vote, votes were cast, and then the Electoral College came in and magically thwarted the results. But that’s not how politicians campaign in the United States. A basic finding in political science is that the way parties run campaigns, the people they choose as candidates, and the platforms that they run under all depend on the kind of voting system in place. If we didn’t have an Electoral College, we would have differently run campaigns, differently constituted parties, and possibly different candidates with different platforms. It’s not that Clinton necessarily would have won and Trump would have lost—rather, we’d probably have had two different candidates altogether. In that sense, the Electoral College isn’t simply thwarting the popular vote; it’s ensuring that there is nothing that we can meaningfully call the popular vote in the first place.

bouie: That’s an important point. But it’s also important to note that even as we recognize that there isn’t really something called a popular vote that accurately reflects the American electorate’s preferences, there has also been, at least since the 1820s, a widely held understanding that the candidate who wins the most votes should become president.

In 1824, John Quincy Adams won the presidency despite winning fewer votes than Andrew Jackson. This created a legitimate scandal; in fact, this is where the term “corrupt bargain” comes from. So even if we recognize and accept that one of the possible outcomes under the current system is a minoritarian president, I think people are still justified in feeling very disturbed by that prospect.

Under conditions of lower political polarization, a winning candidate who won a minority of votes might recognize that fact by forming a kind of unity government. But as we’ve seen over the past four years, and as we certainly saw from 2000 to 2004—we’re living in a high-polarization situation where a president who wins a minority of the vote is going to govern as if he won a decisive majority anyway. That, too, leads people to be highly disturbed by the prospect of a minoritarian president.

allen: Jamelle’s point is a good one, but I would mention alongside his intuition that the president ought to win the most votes an equally compelling intuition—that you can’t have a viable constitutional democracy if, from the get-go, some people know that they’re always going to lose. So, in addition to having majority-protecting mechanisms, you have to also have minority-protecting ones. The question is really one about equilibrations. How often do you depend on the majoritarian intuition? How often do you depend on the minority-protecting intuition?

You know, if the Electoral College functioned in such a way that you knew that the odds were that you’d have a minoritarian outcome only once every forty years, then we would tolerate the moment when the majoritarian intuition felt thwarted. We would recognize that there was another intuition that needed a certain amount of space for the whole system to remain valid and viable. But the sort of demographic shifts we have undergone have changed the frequency with which each intuition is going to be activated at any particular point in time.

For me, that means we have to reorganize certain mechanisms. One solution would be expanding the House, which wouldn’t get rid of minoritarian outcomes entirely, but would shift the frequency of those outcomes back in a direction that’s sustainable as opposed to one that will, without question, undo the legitimacy of a constitutional democracy.

smarsh: As a progressive who resides in a so-called ruby-red state where my vote in national elections has more or less never counted, I think that one of the most overlooked and dangerous consequences of the Electoral College doesn’t pertain to election outcomes, but to the distorted vision it presents of our country.

The map of red and blue states that has reigned on cable news for the past twenty years is incredibly misleading. I’m not a statistician, but based on victory margins across the country, roughly two out of five U.S. voters vote for the party that loses in state and national elections. That’s millions of people whose perspective has been rendered invisible. The idea of red and blue areas might help politicians determine where to spend their resources, or help pundits predict outcomes, but it’s a reductive, even silly, way to understand our true political fabric.

brennan: People’s votes count differently. My vote counts more now that I live in Virginia than it did when I lived in Massachusetts. It would count less if I moved to California.

smarsh: Right, and that distortion becomes a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. Yes, there are political calculations that distort the campaign process and election outcomes, but there are also media distortions that damage the accuracy of our self-regard as a people. And that mistaken sense is perpetuated, in part, by the cynical decisions determining who is worth visiting during a campaign.

iv. achieving our democracy

beha: We’ve established that our system greatly distorts the way in which politicians run campaigns and doesn’t accurately reflect the popular will of the electorate. Assuming we don’t jettison our system entirely, what practical solutions might we consider to remedy these problems?

allen: For me, the electoral mechanism that might break up the scenario in which every state is either all red or all blue is ranked-choice voting. That might be a way to balance the majoritarian and minoritarian intuitions in a kind of viable, sustainable, interactive, dynamic tension.

smarsh: I actually cast my first-ever ranked-choice ballot this year. Kansas was one of five states in which the Democratic Party decided to use ranked-choice in the primaries. And even though I knew that Biden would be the nominee by the time I voted, it still felt validating to make a gesture or statement with my order of preference for other candidates. Again, so much of the trouble with the systems we’re discussing is not just about faulty structures, but about the damage that has been done to our national morale after decades, or even centuries, of failing at true democracy. I’m all for ranked-choice. I dug it.

allen: Ranked-choice does a much better job of making votes meaningful. If you were to imagine one equally meaningful vote for every person, you get a lot closer to that with ranked-choice. You can’t elect somebody when a majority of people opposes them. That’s the key thing. But there are other advantages as well. People have the opportunity to fully express their preferences, so the information value is much higher. Evidence indicates that ranked-choice brings a more diverse pool of candidates into play: more women, more people of color, more minorities. And other research suggests that it tends to make campaigns more moderate.

taylor: Even though I’d also like to see ranked-choice voting, I’ll try to offer a slight defense of the current system, and it actually has to do with what Danielle was just saying about moderation. There’s an interesting book by Amel Ahmed called Democracy and the Politics of Electoral System Choice about how more proportional systems of representation emerged in Europe. The argument is that this typically happened only when one of the main two parties was under threat of being captured, either by the radical left or the radical right. Having a more proportional system was a way of maintaining a degree of control, because you didn’t have to worry about losing the party.

The weakness of a two-party system is also its possibility—if you can actually manage to capture one of the two main parties as a fringe group, then winner-take-all is to your advantage. If the Sanders coalition had managed to win the primary, then the Sanders coalition would be at the helm of the Democratic Party. And then you have a lot of power.

beha: That’s what Trump managed to do.

taylor: Exactly, that’s what the right did. We can imagine an American scenario where there’s a more proportional system, and either because of ranked-choice voting, or a multiparty system, Trump’s coalition was marginalized as part of a fringe party. But with a two-party, winner-take-all dynamic, there’s a huge potential upside to trying to capture one of the parties. Sadly, the left failed to accomplish this.

beha: Another frequently cited idea for improving our elections and increasing institutional responsiveness is compulsory voting. Would this be a good idea in the United States?

brennan: I haven’t been super impressed with the idea—most of the existing empirical work on compulsory voting has found that the effects are surprisingly limited. It seems to increase satisfaction with democracy, but it doesn’t seem to exert a moderating influence, and it certainly doesn’t show that, “Oh, the Democrats would win all the elections if only everyone had to vote.”

It’s also important to note that most arguments in favor of compulsory voting are not in favor of universal compulsory voting. Here’s a thought experiment. Suppose I successfully force 210 million Americans to vote. There would be, as there always is, a statistical counting error, because we have difficulty counting votes properly. If I instead randomly select twenty thousand Americans and decide that only they get to vote, and either force or strongly incentivize them to vote, we would get a better, more representative sample than if we forced everyone to vote, in part because the statistical error from twenty thousand people would be lower than the counting error is for the total electorate. This sortition system would give you a more accurate, representative sample of what the public actually wants than a system of universal compulsory voting. So, if the point of compulsory voting is to ensure that the actual voting public represents the eligible voting public, you should prefer sortition or voting lotteries to compulsory voting.

allen: I recently co-chaired a cross-partisan commission report for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences called “Our Common Purpose” in which, among other suggestions for strengthening our democracy, we recommend compulsory voting for everybody. If you switch to a sortition model as Jason suggests, you’re not getting the kind of ritualized cultural performance of a normative commitment that’s necessary to sustain constitutional democracy. For me, the question of compulsory voting isn’t statistical—it’s about whether or not you have a culture that widely accepts the notion that we all contribute to making our institutions functional. It’s about the symbolism, the cultural meaning, the shared understanding that we can perform a commitment to one another through the act of voting.

taylor: I’m also for a compulsory system, for the reasons Danielle laid out. But I’d specifically emphasize the amount of progressive energy and money that is spent on get-out-the-vote initiatives each election cycle. These are resources that could be better spent investing in infrastructure and organizing efforts that educate and engage people over the long term instead of just trying to muster minimal turnout. The pandemic has made this worse. I’m thinking of all of the victorious, insurgent small-donor-supported candidates I’ve interviewed in recent months: Nikil Saval, Jamaal Bowman, Jabari Brisport, Cori Bush, and others. They all had to spend so much time educating people not only about whom to vote for, but how to vote.

beha: Even if we were to adopt some sort of compulsory system, we’d still have the question of how expansive that electorate should be. Are we happy excluding noncitizens and felons from voting, for instance?

bouie: My sense has always been that voting eligibility should be maximally expansive, and that if you’re going to restrict voting for a group of people, you need a good reason to do it. Part of that just reflects the admittedly tautological belief that universal suffrage means universal suffrage—that there’s nothing about serving time for a felony, for instance, that automatically renders you unable to weigh in on the political community in which you live, a community in which you certainly have a stake. Prisons are one of the places where the state’s hand is the heaviest, so it’s particularly important that people within them have a way of registering their views about how state power is being deployed.

brennan: Most democracies use the right to vote not merely as a way of letting people have their say, but as a way for society to say, “You count as a full member. We approve of you.” Disenfranchising prisoners and felons is society’s way of giving these people the middle finger.

bouie: Right. Being in prison is the punishment for committing a crime. Taking away someone’s right to vote on top of that just seems gratuitous. I don’t think people who support felon disenfranchisement take seriously enough what it means to be deprived of your liberty by being confined to jail or prison. Anyone who has had that experience would not take the idea of taking away additional rights so lightly.

allen: When the Constitution was designed, there was a widespread understanding that in a democracy punishment began with disenfranchisement. Since the earliest democracies on this planet, violating the law has been punished by the loss of political rights. In other words, the fact that you were a lawbreaker meant that you had broken your contract with your community, and the first thing you lost were your political rights. This was true in ancient Greece. It was true in ancient Rome. It was true in early modern republics. So to the Founders, and to some defenders of the current system, disenfranchisement is not an extra punishment—it’s the starting point.

taylor: Building on this, it’s interesting to think about the 2018 ballot measure in Florida that restored voting rights to most felons upon completion of their sentences, affecting around 1.4 million people. Then the Republicans passed a law that said, in essence, that people who still had debts from incarceration would not be allowed to vote. No surprise: court-related debts are extremely common. This harks back to another deeply rooted American idea, one that holds that poor people and debtors are less capable of self-rule. The basic idea is, if you’re a debtor, if you’re someone who lacks property and who owes money, then you’re not capable of being a full, self-governing citizen and you can be disenfranchised. Whatever the ultimate result, it was heartening to see the public vote that way, to attempt to re-enfranchise their fellow citizens.

allen: I agree. That was one of the most important votes any state has made in the last decade. And it’s a good illustration of another sort of history that we often forget about. Voting is not some monolithic thing—it’s been fragmented and contested throughout American history. It’s not actually the case, for example, that the Constitution established that only white men with property could vote. In fact, there were women who could vote up until about 1806.

taylor: And noncitizens could vote in local, state, and federal elections and even hold office until 1926. Today we take the connection between citizenship and voting rights for granted, but they can be decoupled and were decoupled in the past.

allen: Exactly. There have been moments of egalitarian inclusion, if not full egalitarian inclusion. But no such moment of inclusiveness is any kind of guarantee of its durability. It remains contested.

beha: What about the question of voting age? Is eighteen an appropriate cutoff?

brennan: Few countries let people vote before eighteen, and I don’t know if anyone lets them vote before sixteen. The argument is usually that twelve-year-olds are ignorant, twelve-year-olds are uninformed. And they’re right. We have statistics about how much they know. But there’s a problem here if you say, “This fourteen-year-old is not allowed to vote because they’re this ignorant.” I can find 40 percent of the U.S. population that’s also that ignorant. What’s so special about that?

So, most of the arguments you see in favor of disenfranchising the young also apply to much of the rest of the population, but they’re allowed to vote because they’re older. The argument about ignorance is not really doing the work in explaining why older people can vote but younger people cannot.

bouie: To my mind, there’s no reason that a fourteen- or fifteen-year-old shouldn’t be able to vote. Many of the arguments against letting younger people vote—they’re too dependent, or they lack the mental capacity—are identical to what you’d say if you were trying to ban an eighty-five-year-old from voting, right? At a certain point, just let people vote!

taylor: I think there’s a strong argument to be made for letting younger people vote. I would say as young as twelve, maybe younger. We are effectively living under a gerontocracy—our electoral system is massively tilted toward older Americans, who tend to be whiter, more conservative, and more affluent than rising generations. This is deeply unfair, especially when you consider climate change, something millions of young people are well informed and passionate about. I mean, the results speak for themselves. I doubt we’d have a worse president if kids could vote. Though, given young people’s affection for progressive figures such as Bernie Sanders and Ed Markey, we might still have an old one.

v. what’s in a vote?

beha: We’ve been circling around a few different ideas of what voting actually means or does. Some of you have emphasized its informational value, or its usefulness as a mode of expression, or its role as a duty essential to the functioning of a robust democracy. What, I wonder, is voting actually for, then, and how might that understanding guide our decisions in the voting booth?

brennan: For me, it depends on what’s happening when I vote. Right now, when I wave my hand, nothing happens. But if it turned out that waving my hand could prevent the election of a terrible dictator, well, then that would change my obligations. But if nothing is going to happen, then it’s just something I’m doing to express myself.

I think something similar holds for voters. On one hand, if—as will be the case for most people—you’re in a state where the probability of your vote deciding the election is vanishingly small, you should feel liberated to vote expressively. But if you are in a state where it looks like there’s a good chance that the election will be tight, and so your vote has a significant chance of deciding the election, then you should be strategic. In that case, if you want to express your support for a third party, or cast a protest vote, you could write a poem, or write a letter to the editor, but you should vote for the better candidate.

bouie: The problem with that idea is that it’s not immediately obvious whether or not your vote will matter, right? If you were a voter in Michigan in 2016, history and polling would’ve suggested that your vote was probably not going to matter much and that Hillary Clinton would likely win the state. But that didn’t happen.

Precisely because we can’t know what the future will hold, I’m always inclined to encourage people to do the most prudent thing in that moment. If you oppose Donald Trump, and the election is between him and one other person, then vote for the person who is not Donald Trump.

smarsh: While I was not one of them, I knew some very thoughtful people who cast third-party votes in 2016. And while I didn’t agree with their tactics, I likewise didn’t appreciate their subsequent vilification, as though their stance was somehow entirely to blame for the outcome.

I agree with Jamelle that when there’s a crisis afoot we ought to tend to the crisis, and we can’t afford to be expressive in the way that Jason described. I don’t mean to suggest that a distinction between moderates and progressives is unimportant or just a matter of nuance, but it’s not the difference between dictatorship and democracy.

taylor: Yeah, at this point, as an organizer on the left, I’m casting a ballot for the person I want to be my adversary. In that sense, I think people are mistaken when they think of casting a ballot for the presidency as an affirmative thing: “I’m voting for the person I like.” That’s not the case for me. I’m voting for the person that I want to be in an antagonistic relationship with as an activist, and that is not Donald Trump, because I’ve spent the past fucking four years holding the line on the tiny little wins we got under Obama.

There was something powerful about the margin by which Donald Trump lost the popular vote. On a fundamental level it did undermine his legitimacy. In that sense, even if you’re not in a swing state—if you’re in a safely blue state—that number has mattered over the past four years. So that’s an argument for casting a ballot even when the direction your state is going in seems to be preordained. Though I do worry that certain bets are off with the pandemic, and that some states may not be as “safe” as they normally seem.

I’m still very much with Sarah, though, and I don’t think people need to be vilified for third-party votes. But if I’m going to express myself, voting third-party is not going to be my top form of self-expression. There are lots of other, more expressive things to do. I’m all for the poem that Jason mentioned. It’s not just that third-party or “protest” voting is not strategic; it’s not even a satisfying or cathartic form of self-expression.

bouie: Here are the questions I’m asking myself in the voting booth: What kind of politician do I want to have to petition in the future? Who do I want to have to challenge or argue against? Who do I want to staff the federal bureaucracy? These are the concrete questions that voting in expressive terms too often obscures. When voting becomes a question of your immortal soul, it becomes difficult to see the very practical things that are at stake.

allen: I’d suggest that the kind of vote Jamelle just described is, in fact, expressive. It’s expressive of an approach to politics. In that regard, any vote is expressive. Any vote conveys a set of commitments, as well as information about the spread of those commitments across the electorate.

brennan: For most people, I’d add, the commitments that voters are expressing are not fundamentally about politics or ideology. A good analogy is sports fandom. I’m a fan of the Boston Red Sox and the New England Patriots, not because when I was eight I looked around and tried to figure out which were the best teams, or because I determined that these teams best represented my values, but because I grew up in New England, and that’s what you do to be a good New Englander.

There is very strong evidence that, for most people, voting is fundamentally an expressive action about coalition-building, and that we join parties and vote for social benefits. We’re just waving flags. I’m trying to show that if I vote Democratic, I’m a proper college professor. Or that I’m a proper Irish person from Boston. If I vote Republican, that means I am a proper Southern evangelical, and what’s more, other Southern evangelicals can be my friends and do business with me.

allen: But at this point, the majority of people are no longer members of a party. I’m not sure the party-affiliation analysis really sticks.

brennan: Well, most people who don’t belong to a political party almost always vote the same way. People say, “I’m an independent,” but they’re almost all so-called closet partisans and vote more or less exclusively for Democrats or Republicans.

smarsh: I have found that a sense of rooting for a team influences a community to vote in one majority direction. The increasing tribalization of American politics is something I’ve observed very directly over the course of my life here in Kansas. When I was coming of age and coming into political awareness in the mid-Nineties, conservatives were attacking liberals with self-righteous venom. Newt Gingrich was holding forth in Congress; Rush Limbaugh was taking over the radio airwaves; Fox News was emerging as a powerhouse. Because of those efforts, politics is no longer just your ideas—it’s your identity, your team. That conservative strategy woke up the opposition, too. Many of the people I grew up around who didn’t pay attention now pay very close attention as newly activated progressives. But for conservatives in particular, politics has become entertainment, a blood sport that offers the thrill of belonging.

beha: In other words, these are people whose sense of belonging might outweigh, say, their inclination to vote for a candidate whose policies are more aligned with their self-interest. And maybe those who feel the strongest, most zealous sense of belonging wind up being those who are motivated to go to the polls.

taylor: Again, this is why the idea of expanding the electorate is so important. The electorate is not a stable thing—the demos changes over time. And democracy isn’t a poll, an account of what people think at this exact moment. It’s something that we can work to change, to transform, to expand.

allen: That’s really well said. The challenge is to build public conversations that lay out clear ways of thinking about what self-interest is, and whether or not self-interest is tied to the well-being of the whole.

It’s politics, man! That’s where the work is, that’s the whole point. That’s the fun, that’s the fight. That’s where we get to figure out who we are as a people, where we get to shape the culture. That’s why it’s good stuff.