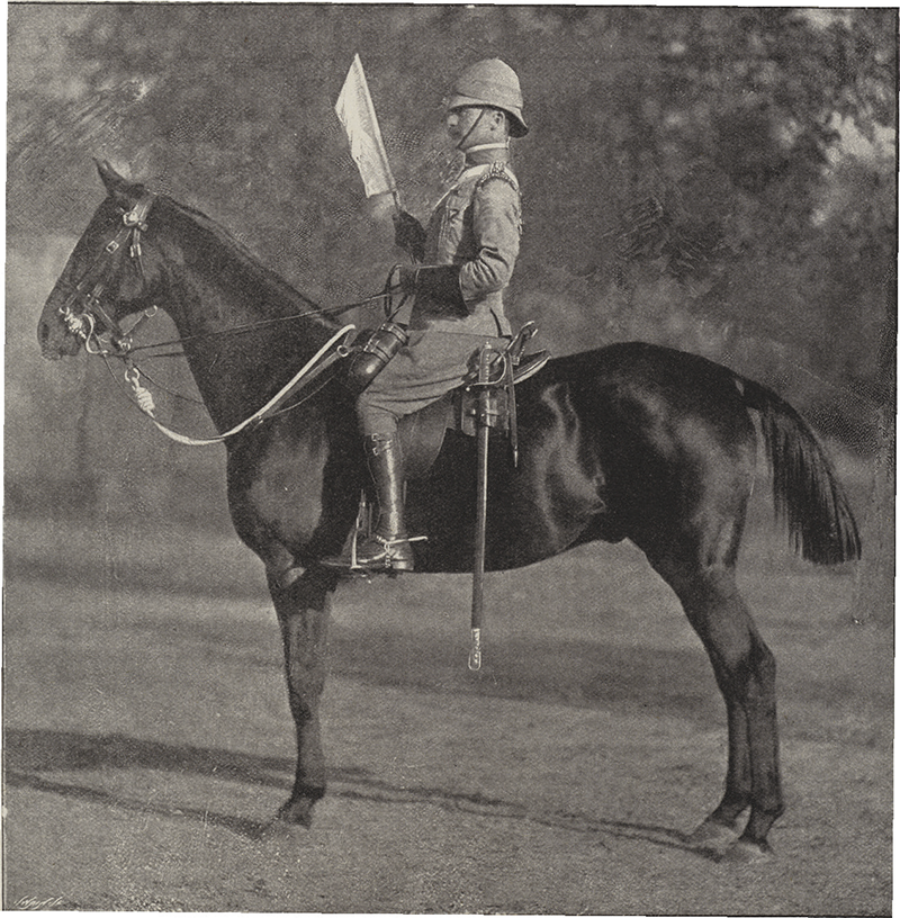

Colonel Robert Baden-Powell on his charger, Aconite © Look and Learn/Illustrated Papers Collection/Bridgeman Images

Discussed in this essay:

Character: The History of a Cultural Obsession, by Marjorie Garber. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 464 pages. $32.

Throughout the United Kingdom, local authorities have eyes on their public statuary, nervous for the safety of racist city fathers and colonial movers such as Oliver Cromwell, Cecil Rhodes, and Winston Churchill (whose imperialist dodges are hardly recognized as such by many English people). Not long ago in Bristol, a late-Victorian bronze of the seventeenth-century slave trader and Tory parliamentarian Edward Colston was torn from its plinth by protesters and thrown into Bristol Harbour. Even the founder of the Boy Scouts, Robert Baden-Powell, is at risk. In Poole, his figure sits, walking pole in hand, just a few meters from the sea. Not for the first time, his racist and homophobic attitudes—not to mention an approving 1939 diary entry about Mein Kampf—have been recounted in the news, condemned, and defended. The local council boarded up the statue for a month to protect it from protesters. In Dorset, and in the British media, Baden-Powell’s character is at issue.

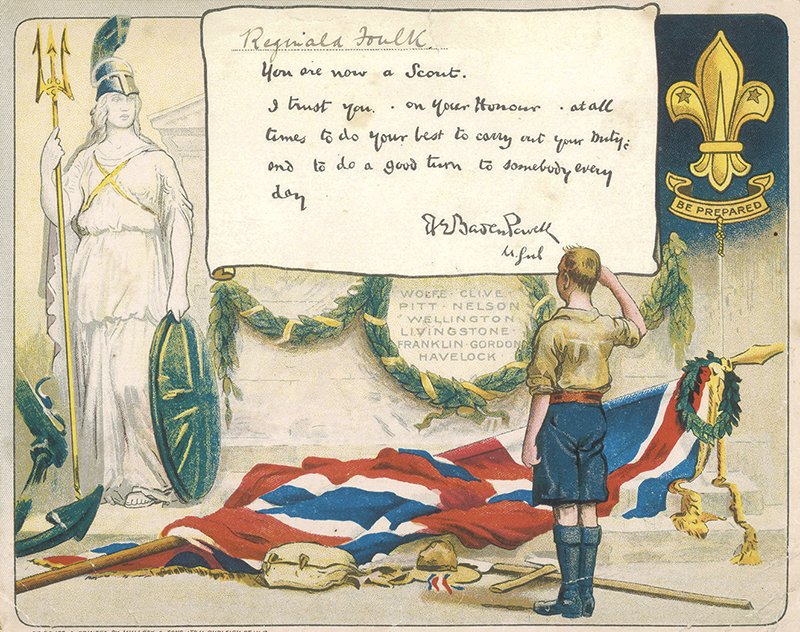

“Character” was one of Baden-Powell’s favored terms for the mix of moral rectitude, athletic prowess, patriotic idealism, and practical woodcraft that he hoped to ingrain in a Scout. (Some of it applied also to Girl Guides—but sports might well derange, in the words of his sister Agnes, “a woman’s interior economy.”) In her absorbing study Character: The History of a Cultural Obsession, Marjorie Garber tells us that to Baden-Powell the Boy Scout movement was a “character factory” for producing clean-living and right-thinking young Englishmen. Or not quite men; in his 1908 book Scouting for Boys, Baden-Powell preferred to call them “Rovers”—those still at the vital, urgent, therefore perilous stage of male adolescence. Among the Scout Laws designed to encourage and direct a Rover’s character: “A Scout is Loyal,” “A Scout is Thrifty,” “A Scout is a Friend to Animals,” “A Scout Smiles and Whistles Under All Difficulties.” A more notorious law was added in 1911: “A scout is clean in thought, word and deed.” That is to say, he does not masturbate. Baden-Powell’s original typescript had gone further: “A very large number of the lunatics in our asylums have made themselves mad by indulging in this vice although at one time they were sensible cheery boys like any one of you.”

A scouting certificate from 1914, with a note written by Baden-Powell © Chronicle/Alamy

So much for character as a dirigible quality that Scouting for Boys sets out to teach. As Garber reports, Baden-Powell’s book also deploys another quite different conception of character—as innate rather than acquired, a trait to be discerned (or not) in others, a standard by which they may be judged, approved, censured, or shunned. In his fourth chapter, on tracking and observation, Baden-Powell advises his young readers:

When you are travelling by train or bus, always notice every little thing about your fellow-travellers. Notice their faces, dress, way of talking, and so on, so that you could describe them each pretty accurately afterwards.

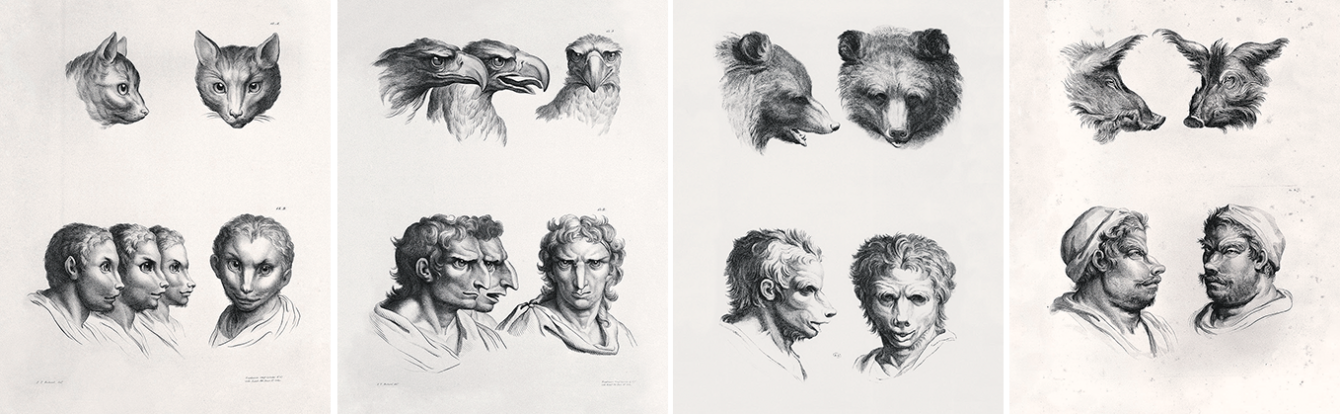

By scrutiny of a traveler’s boots, a Scout will know his or her station in life; and by observing the angle of a man’s hat, whether he is good-natured, a “swaggerer,” an honest dullard, or “bad at paying his debts.” (Baden-Powell does not admit that the seemingly legible passenger may be feigning class or character—or sincerely striving to alter the same by force of will.) As for what is going on beneath the hat, Baden-Powell supplies three of his own line drawings to depict various characters. They show, in profile, a boy with a large nose but neither chin nor much forehead, a beatific youth of vaguely classical aspect, and an older man with tight curly hair, a furrowed brow, and a prominent mouth. As Garber points out, the last character is not necessarily meant to be black. (His features are also those seen in Victorian or Edwardian caricatures of the Irish and the English poor.)

Garber devotes around twenty pages to Baden-Powell and his seemingly sturdy but conflicting ideas about character. All of this—an easily mockable belief in “manliness,” the seeming necessity of an entire quasi-military organization to aid in achieving that state, and his blustering insistence that you can spot its temperamental antipodes in the shuffle or slouch of a passing pedestrian—displays the central, organizing ambiguity in Garber’s book. “Character” names at once an ideal or aspiration and an ineradicable mark; a state to be arrived at by will; and a condition requiring education, leadership, and propitious circumstance. “Is character innate, learned, taught, or instilled? Are character traits fixed or changeable? Do they depend on heredity, on environment, on parents, teachers, mentors, or life experiences?” Garber asks versions of these questions throughout, but she considers them chiefly literary—that is, “questions about the way something means, rather than what it means,” as she put it in The Use and Abuse of Literature—and so they do not require or perhaps even invite exact answers. Instead they describe a historical perplex of inquiry and assumption, bodily as well as spiritual discipline and license, morality and its performance, that will not settle but continues to bear on private and political life, even if the word itself seems today an inadequate descriptor: “At a time when political corruption, sexual harassment, and renewed attacks upon blacks, Jews, Latinx, LGBTQ people, and immigrants are reported daily in the news, the idea of ‘character’ may seem a quaint survival from a more naïve, more ethical, or at least less brazen past.” Still it persists, and adapts.

A series of lithographs by Charles Le Brun. Third from left: © Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images. All others: Courtesy the Wellcome Collection, London

“Character” sometimes seems so general a term that it threatens to melt into personality, morality, psychology, ambition, will, influence—or to reveal itself merely as a rhetorical sleight with no real value or referent. The strength of Garber’s book therefore lies less in adducing a present value for the concept than in her wide-ranging account of how we arrived at the confused and confusing things it has meant and means now. Character has been a key term in the history of modern education, a quality to be nurtured, and noted in its absence. It has been subtilized by psychiatric science and pseudoscience, and deployed as a backdrop to the parlor game of phrenology, which is one origin for our modern medicalized ways of judging one another. It is the point at which image and idea meet, in the linked histories of medicine and marketing, especially political marketing. The civic use of the word appears frequently to imply a kind of nostalgia: character is usually vanishing over the horizon. It is almost always, today, a historical category.

Garber traces the philosophical history of character back to Aristotle, arguing that it is essentially what the Nicomachean Ethics introduces as virtue: “a state of character concerned with choice, lying in a mean,” i.e., the so-called golden mean between two states, one involving excess, the other deficiency. Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor as head of the Lyceum, anatomized character explicitly in terms of types. The list of Theophrastian characters, who are all representatives of social, moral, or intellectual extremes, include: the dissimulator, the flatterer, the bore, the loquacious man, the coward, the oligarch, and the late learner. These can seem quite modern. Garber quotes the classicist Mary Beard: “These Characters are people we know—they’re our quirky neighbors, our creepy bosses, our blind dates from hell.” But they are quite unmodern precisely in being types in the first place: they do not alter in response to circumstance, and lack the idiosyncrasies that are essential to the assessment of character in modernity, from Montaigne to Rousseau to Freud. Curiously, neither Montaigne nor Rousseau feature in Character beyond a passing mention of the former; but the Freudian focus on character (or personality) as a social problem rather than a moral entity—this is where much of Garber’s interest lies.

But whence this term, in its various English senses? Among its first meanings, in the fourteenth century, was a quality instilled or infused by the Christian sacraments of baptism, confirmation, and holy orders. If the concept seems related to Aristotle’s ethos, the word itself derives from a Greek cognate, meaning a die, stamp, or impress: a characteristic mark or symbol, as well as the instrument for making such. Already there is some slippage between surface and interior: the action conjured by the word is a graving, cutting, or styling, but also a kind of branding. Character is something flatly legible, significant, and at the same time carved into body or object. And as Garber has it, process and meaning have not ceased to overlap in modern use:

Over time, the notion of being engraved or “written” became associated with what we would now call character traits or dispositions, both on the stage and in social and political life. For a long time, this idea of character as something akin to persona or personality was the dominant one in common usage.

A character might also be a visual or textual portrait, a witty description of certain types or caricatured persons—after the writings of Theophrastus.

Garber, who is an English professor at Harvard, is well-placed to say what has been meant by the word, and how it operates today. As a prominent scholar of Shakespeare—her study Shakespeare After All was published in 2004, at a thousand pages—she knows how his plays’ complex ideas about personality and performance may thicken into mere self-help bromides, adult versions of the bootstraps advice Baden-Powell directed at his young charges. In Character, Garber notes some titles of recent business books—Power Plays: Shakespeare’s Lessons in Leadership and Management, Shakespeare in Charge: The Bard’s Guide to Leading and Succeeding on the Business Stage—but the tendency to derive more or less banal wisdom about life and money from Shakespeare’s plays dates at least from the beginning of the nineteenth century. In fact:

In psychological, sociological, and sometimes philosophical terms—as well as in literary studies—it is often Shakespeare who defines character and character types for the modern world.

Garber quotes John Foster, a Baptist preacher who in 1804 published an essay titled “On Decision of Character”; his ideas of boldness and resolution are explicitly related to the likes of Richard III, who, says Foster, “did not waver while he pursued his object, nor relent when he seized it.”

Garber has also written academic works about bisexuality and cross-dressing, in which she explores the cultural anxieties attached to identity. Though its terminology may seem old-fashioned now, her 1992 book Vested Interests is in some ways a related project to the present one, examining the ambiguous overlap between travesty and gender identity. And she has also written books about dogs and real estate. As in some of these earlier works, Garber’s approach in Character is broad and thematic, touching relatively lightly on each of her many historical or textual examples. The book’s eight chapters address such topics as politics and celebrity; character and education; typologies and their relation to physiognomy, phrenology, and psychoanalysis; and historical certainties (and their undoing) about gender and nationality.

Her account of character as a literary and cultural category, and how it has literally or figuratively been read in real or imaginary individuals, may well be the book’s strongest aspect. The modern understanding of character, she argues, is not just adjacent to, but actually derived from, fictional characters: their construction on the page, but also their concerns about the character of their peers. The nineteenth-century English novel, well stocked with memorable persons who may serve as exemplars or warnings, is fixated on character, its formation but also its legibility, especially in a period of increasing social and economic mobility, when personality and “prospects” (as Dickens has it, for example, in Great Expectations) were hard to tell apart. To be the protagonist of a novel by Charlotte Brontë, for example, is in large part to be a reader with a brief to discover the tenor and temperament behind outward show. More than this, it’s to be the kind of reader who sees further and discerns more than others, whose sensibility picks up tremors of latent personality that nobody else feels. In Villette (1853), the introverted heroine Lucy Snowe is the only one able to recognize, across a crowded theater, the blight of melancholy in the face of the king of Labassecour, a fictionalized Belgium. And in Brontë’s first novel, The Professor (unpublished in her lifetime), the young schoolteacher William Crimsworth spies deficits of character in the gaunt faces of his slovenly and shameless female pupils: ill-temper on the forehead, vicious propensities in the eye, deceit and envy about the mouth. This lurid catalogue of faults points to the characterological drama of this and other novels: so super-sensitive a reader is apt to get it wrong.

Among Brontë’s novels, Garber’s focus is especially on Jane Eyre, with its heroine’s curiously keen attention to the features of Mr. Rochester. Here is Jane, staring at his forehead:

He lifted up the sable waves of hair which lay horizontally over his brow, and showed a solid enough mass of intellectual organs, but an abrupt deficiency where the suave sign of benevolence should have risen.

She is employing the vocabulary of phrenology, a then-modish pseudoscience that also captivated her inventor. Four years after the novel was published, Brontë visited Dr. Browne, a phrenologist with an office in central London. In his “phrenological estimate” of the novelist, Browne asserts:

Temperament for the most part nervous. Brain large, the anterior and superior parts remarkably salient. . . . She is occasionally inclined to take a gloomier view of things than perhaps the facts of the case justify.

No matter—well, little matter—the accuracy of the head-bump specialists: by midcentury, phrenology had supplied its practitioners, as well as writers and the general public, with a lexicon for character. Some of the more rebarbative terms have vanished, and others survive as relics of an era when it was fashionable to speak of one’s own or others’ Firmness, Cautiousness, Ideality, Destructiveness, Continuity, Amativeness, Philoprogenitiveness (love of one’s own children), Self-Esteem, or Selfishness.

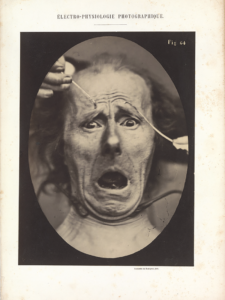

“Figure 64,” from Électro-Physiologie Photographique, by Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne and Adrien Tournachon. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

We should not rush, writes Garber (who is following Stephen Jay Gould, among others), to dismiss phrenology as simple period quackery; it’s an essential stage in the slow development of psychiatry, if only for its adherents’ hunch that certain parts of the brain had particular jobs to do. Just as important for Garber’s purposes, phrenology is an example of scientific vocabulary leaching into everyday description and understanding of character or personality. In fact, “personality” is another instance of the same terminological drift: psychologists came to prefer the term to distance their ideas from the ethically freighted “character.” It’s possible to be a personality and to have a personality, good or bad, attractive or ugly, hampering or auspicious in the business of getting ahead. Garber also points out that a comparable process has occurred with the traits and disorders of personality that contemporary psychiatry describes:

DSM-5, since it is concerned with diagnosing disorders, gives a list of what it calls “maladaptive variants” of the “Big Five,” naming as the five broad domains of personality-trait variation Negative Affectivity (versus Emotional Stability), Detachment (versus Extraversion), Antagonism (versus Agreeableness), Disinhibition (versus Conscientiousness), and Psychoticism (versus Lucidity).

As an example of the popular migration of psychiatric terms, consider the ease with which, as laypersons, we feel qualified to diagnose narcissistic personality disorder among our ex-lovers, bosses, and political leaders.

As Garber has it, phrenology derived in part from a longer history of physiognomy and its visual record of character, whether fixed or fleeting. At the more avowedly artistic end of this tradition: the seventeenth-century drawings of Charles Le Brun, in which he delineated the human “passions” and compared their expression to the faces of animals. And the sculptural Kopfstücke, or “head pieces,” in which, at the end of the eighteenth century, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt depicted violent or grotesque states of feeling or character. (An exhibition catalogue later gave the heads—which had been modeled on the artist’s own—such titles as The Vexed Man, The Difficult Secret, The Incapable Bassoonist, A Hypocrite and Slanderer, and Afflicted with Constipation.)

But it’s the nineteenth century’s photographic attention to character that really exercises Garber. In 1862, the French neurologist Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne published The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression, with one hundred photographs showing different emotional states. Duchenne had suborned as a sitter an elderly male patient from the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, and for some of his photographs administered electric shocks to elicit a particular grimace. (Charles Darwin republished some of these images in his 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.) In Duchenne’s images, and in the studies of hysteria that his pupil Jean-Martin Charcot made later that century, character is a secret that reveals itself under close scrutiny, and a set of behaviors that the subject is stimulated or trained to do, captured in their performance. (The machinery that Duchenne used to generate, or mimic, looks of surprise, fear, or delight in his patients is visible in some of the photographs; elaborate protocols of rehearsal, staging, and repetition were required for Charcot’s images of apparently spontaneous hysterical attacks.) Again, one has character, but also becomes a character, a combination that Erving Goffman describes in his 1961 study Asylums: the patient makes a “primary adjustment” to the institution, and a “secondary adjustment” to maintain some sense of self while living there. Goffman had already generalized this experience in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life: “In our society, the character one performs and one’s self are somewhat equated, and this self-as-character is usually seen as something housed within the body of its possessor.” As Garber puts it, Goffman elaborated this concept of the performed self “long before the heyday of social media and the ‘selfie.’ ”

The Vexed Man, by Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Another name for the performance of character, in special circumstances, is “discipline.” The seeming contradiction between innate and acquired character—this is meant to disappear with training and education. In 1816, Garber tells us, Robert Owen founded his Institute for the Formation of Character in the utopian community of New Lanark, southeast of Glasgow. Under the influence of thinkers such as William Godwin and Erasmus Darwin, Owen set out to educate children and adults with a curriculum that included music, dancing, and games. This schooling, Owen said, was meant to improve “the internal as well as the external character of the whole village.” There were some famous objections to his methods: the poet Robert Southey visited the Institute in 1819 and declared that it resembled a plantation, the pupils Owen’s slaves. John Stuart Mill, who rejected what he thought was Owen’s fatalism, supplied the term that would, for the rest of the century and well into the next, secure a peculiarly British notion of internal and external character. Sheer force of will—with its boyish cognates of “spirit,” “gusto,” “manliness,” and “vigour”—was the motor of British imperialism, set running on the playing fields of its public schools.

Something of Mill’s robust notion of character survives, says Garber, in the American pursuit of “character education”—a lineage she traces back to Benjamin Franklin and forward, via L. Frank Baum, to Donald Trump. Character education is another attempt to resolve the disparities between discipline and expression, free will and moral imposition, personality and performance. When the Wizard of Oz hands the Scarecrow a diploma, the Tin Man a testimonial, and the Cowardly Lion a medal, he ratifies externally what was already inside, even if they did not know it. The contemporary version is certainly banal. CHARACTER COUNTS! is a heavily marketed program—the product of the Josephson Institute of Ethics (the uppercase shouting is the organization’s own)—founded in 1992 by former law professor Michael Josephson and dedicated to inculcating in America’s youth the “Six Pillars of Character”: trustworthiness, respect, responsibility, fairness, caring, and citizenship. Garber regards the program and its rhetoric as part of a wider conservative embrace of values by which social ills are claimed to be overcome through the development and exercise of individual traits. The program’s stated aim is to “overcome the false but surprisingly powerful notion that no single value is intrinsically superior to another.” In October 2017, Trump became the fourth president to affirm in writing the veneration of character itself:

We celebrate National Character Counts Week because few things are more important than cultivating strong character in all our citizens, especially our young people. The grit and integrity of our people, visible throughout our history, defines the soul of our Nation.

The ironies involved in this presidential employment of “character” probably do not need pointing out. Garber returns to Trump in her final chapter, concerning character and gender, and in her afterword, where she quotes him describing Brett Kavanaugh in October 2018 as “a man of great character and intellect.” Garber is correct to say that a peculiar locution has emerged in recent years, employed by the likes of Kavanaugh to rinse away past sins. In a brazen assertion of the gap between the supposed truth of character and the sorry accident of behavior, one simply says, “That is not who I am.” But this distinction between pure interior and fallen exterior is just what is denied those whom the president attacks—especially women, who are in his mind reducible to his puerile judgment of their physical appearance. So also, of course, people of color, trans people, the disabled, and many more. Garber assures us:

My point is not (just) to deplore these personal comments about mood and appearance, but to emphasize that they are also implicitly—and sometimes explicitly—assessments of character, as the contemporary world understands that concept.

Garber hopes that, instead of this viciously essentializing version, a more idealist, innocent, moral sense of character might survive, even if it will necessarily seem antique, a relic of Victorian self-improvement and twentieth-century self-help. She comes down on the side of continuing to use “character” to describe human action, good or bad:

It is not an essence, but a mode of behavior, or a habit of being; a verb or a gerundive rather than a noun or a string of adjectives; an effect, not an image; a lifelong process, not a merit badge.

The implication of this position must be that the other, intrinsic sense of the word would somehow fade away, or function only vestigially, like the phlogiston theory of combustion entertained by eighteenth-century chemists—an invisible, unprovable substance explaining what is seen. As Garber writes, belief in phlogiston did not yield easily to new knowledge: “The idea of phlogiston found a place in literature and culture even as it was losing its relevance to science.” Likewise, there is character and “character”; we know that one of them is not really there.

The richness of this history is what makes Garber’s book fascinating, and also, perhaps, the reason she does not want to relinquish the idea at the last, and instead hopes that there is intellectual and ethical life in a word that has outlived its history. But would we really want it, when this other sense is all too hale and prevalent, the perverse habit of aged Rovers?