Illustrations by Patrik Svensson

All happy religious families are alike; each unhappy religious family is unhappy in its own way.

The family of American Christianity has been unhappy for quite some time, so much so that it’s hard for many of us to imagine that it could be otherwise. The past four years have brought these feuds into the open. For Catholics, there is the glaring pedophilia scandal. For evangelicals, there is disagreement over church leaders’ alliance with power, their unwavering fealty, since 2016, to the crotch-grabbing Caligula of Mar-a-Lago, whose every abuse of office made them double down on their support.

For mainline Protestants like me, the discontent has been less visible. Denominational squabbles over human sexuality have made headlines, but across every denomination a certain lassitude pervades, a general lukewarmness that makes it feel as though Protestantism has run its course. When the five hundredth anniversary of the Reformation rolled around in 2017, a few academics published monographs on Luther, and a commemorative study Bible appeared, but with church membership declining in every mainline denomination, Protestant circles shrugged. We knew there wasn’t much to crow about. What was it, exactly, we were still protesting?

Outwardly, it might look as if the family dynasty is on the wane, a decline that deepens with every new Pew study. What of the alternatives? A growing number of people are simply leaving the Christian household altogether, becoming Spiritual But Not Religious. Among some conservatives, there is talk of “strategic withdrawal” into tiny neighborhood enclaves. In The Benedict Option, Rod Dreher asserts

that serious Christian conservatives could no longer live business-as-usual lives in America, that we have to develop creative, communal solutions to help us hold on to our faith and our values in a world growing ever more hostile to them.

Dreher laments “the breakdown of the natural family, the loss of traditional moral values, and the fragmenting of communities,” which he blames on “the flood of secularism.” But the Ben Op, as Dreher calls it, feels a lot like old culture-war stuff repackaged with a catchy title; what Dreher really means by “our values” is protecting the Christian family from “the LGBT agenda.” By accepting gay marriage, his argument goes, the church has failed. “I have written The Benedict Option to wake up the church . . . while there is still time,” he warns.

Meanwhile, those on the Christian left are also digging in politically. The primacy of race-class-gender (in the world of progressive theological education it’s often said breathlessly, as one word) as an interpretive grid, the focus on political advocacy, the intense energy directed toward voter registration or climate justice or affordable housing—all of this can make it feel as if progressive churches have become religious versions of MoveOn. The drive to stay politically relevant makes it hard to talk about prayer or salvation or Jesus, unless it’s a prayer that everybody at a rally can get behind, a salvation that exists in this world, or a Jesus who is just a political rabble-rouser. If conservatives like Dreher fear assimilation, progressives fear being too Christian. Having grown up in one camp (conservative), I long ago threw in my lot with the other (progressive), but my point here is not to promote camps or criticize platforms. It is precisely to say that religious life, to its detriment, has been reduced to a platform.

Like the Kardashians, the American Christian family has become obsessed with its own profile. It has become faith as public spectacle, faith as political engagement, as party affiliation, as reputation—anything but faith as paradox, as mystery, as the hidden and seductive dance between spiritual desire and satiation, the prolonging of a hunger so alarmingly vast and yet so subtle that it disappears the moment it’s made public.

In early monastic Christianity, that hunger was acknowledged and channeled, given shape and form and expression. It went by different names—contemplatio (silent prayer) or hesychia (stillness)—which led first to an inner union with Christ, and then to a deep engagement with the suffering of the world. The order was important. In John Cassian’s Conferences, a fifth-century account of the early Christian monastic movement in the deserts of Egypt, a certain Abba Isaac describes how the monks modeled their prayer on Jesus’ practice of going up a mountain alone to pray; those who wished to pray “must withdraw from all the worry and turbulence of the crowd.” In that state of spiritual yearning, God’s presence would become known. “He will be all that we are zealous for, all that we strive for,” Abba Isaac said. “He will be all that we think about, all our living, all that we talk about, our very breath.”

What the early monks and the Christian mystics who followed sought was union—an intense experience of inwardness that is glaringly absent in what many of us get from American Christianity today. Perhaps this absence is the real reason for the mass exodus from churches. Perhaps it is not Christianity that many followers are disappointed in, but Christendom.

While the mysteries of contemplative Christianity were once handed down by emaciated anchorites in the Egyptian desert, the modern wisdom seeker might find himself, as I did, in the Albuquerque Convention Center, watching Richard Rohr speak on a Jumbotron.

On the last Thursday in March 2019, I arrived at the Universal Christ conference—an event coinciding with the release of a book by Rohr with the same title—along with several thousand other people. Rohr, a Franciscan priest whose books consistently make the New York Times bestseller list and whose Daily Meditations newsletter has nearly half a million subscribers, began the conference by reading from the well-known “water from the rock” chapter in Exodus, the story in which Yahweh commands Moses to strike a rock with his staff, causing a spring to gush forth.

“Sounds like paganism,” Rohr said. The crowd laughed. Water is the one element necessary for life, he continued, which is why baptism by water became Christianity’s initiation rite. “This is why we need to read scripture symbolically,” Rohr said. “Who cares if it happened on this or that day? Who cares? Read it as the unlikely source of life and grace: water from a rock. Symbolic language is true on three or four or five levels, but we’re afraid of it.”

Since Rohr founded the Center for Action and Contemplation in 1987, his aim has been to revive the Christian contemplative tradition. For a growing number of Christendom’s defectors, his teachings have provided a bridge, even a destination. Through conferences, podcasts, dozens of books, a two-year curriculum called the Living School, and his newsletter, Rohr has become a leading voice for a growing population within American Christianity: those who were leaving the church not because they were done with Christianity, but because they were drawn to its more ancient, mystical expressions. In addition to the two thousand attendees from fifty states and fifteen countries, nearly three thousand more people from forty-two countries joined via webcast. I bought one of the last tickets before the conference sold out. To his credit, Rohr is quick to say that whatever popularity he enjoys is not because of himself—“God deliberately made me not so good-looking. I’m short and dumpy, a B student . . . and I don’t think I’m a saint”—but because he speaks on behalf of what he calls the perennial tradition, a lineage rooted in Christianity but that he says is present in all faiths.

The “all faiths” part of Rohr’s message is sincere—he often concludes his prayers with “in the name of Jesus and all the holy names of God”—yet he considers himself an orthodox, Catholic Christian. Part of the delicate balance Rohr has achieved lies in maintaining his institutional credentials. He told me proudly of a call from Cardinal Timothy Dolan declaring his new book free of doctrinal error—while not shying away from critiquing the church and its many failures. Throughout the conference, Rohr dished out a series of barbs aimed at Christian piety.

“How did the church create so many Christians who don’t love the world?” he asked. “We’ve created fire-insurance people. They have an evacuation plan to the next world. They’re fear-based. Why do they have such little spiritual curiosity?”

The message of the Gospels, Rohr later told me, “has been pretty much co-opted by empire, by academia, and by a sort of elegant notion of priesthood that’s disconnected us from the earth beneath our feet.”

The problem is not just with Catholicism. Rohr’s core audience, including many of the people I met that weekend, consists of disaffected Christians of all denominations who feel like outsiders, or perhaps fringe dwellers, and are leery of the established church. Part of Rohr’s appeal is that he keeps one foot in orthodox Christianity while also pushing the boundaries of the faith.

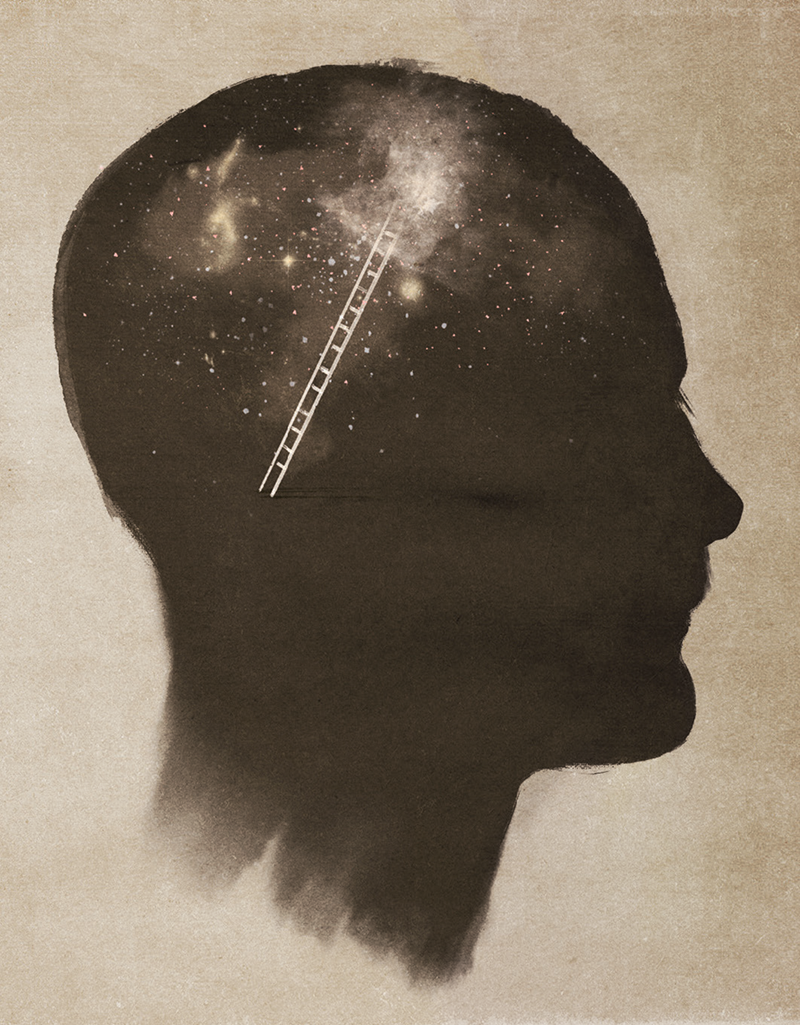

That first evening, Rohr read a passage from Genesis, the account of Jacob’s ladder. In the story, Jacob had left Beersheba and was on his way to Haran when he stopped to sleep. That night, Jacob dreamt of a ladder that reached heaven, with angels going up and down. When Yahweh appeared in the dream and spoke to him, Jacob awoke and exclaimed, “How awe-inspiring this place is! This is nothing less than a house of God, this is the gate of heaven!” To mark the place, Jacob set up a stone monument and anointed it with oil.

“Let’s start by anointing one thing,” Rohr told the crowd, inviting each table to pour oil on the rock in its center. My table watched him on the Jumbotron, then eyed our own rock, something like volcanic basalt, next to a dropper of olive oil.

“You have to be in awe and kneel and kiss the ground before one thing,” Rohr said, holding up his right index finger. “Then you can do that for everything. Jesus is the concrete, Christ is the universal. Wherever you want to kneel and kiss the ground, that is Christ for you.”

Over the next three days, the Universal Christ conference became what the organizers called “a pop-up spiritual community.” With Tibetan singing bowls and periods of communal silence, a certain ceremonial ethos prevailed. I never warmed to the Jumbotron. Still, the gathering felt surprisingly intimate, even worshipful, less like a conference and more like, well, church.

In addition to Rohr, the conference featured two other speakers: John Dominic Crossan, an elfin-voiced Irish New Testament scholar, and Reverend Jacqui Lewis, an African-American preacher from New York. Reverend Lewis gave a talk called “Where Is the Crucified Body of Christ Today?” She invoked Mother Earth and climate change, racism and white supremacy. “The crucified Body of Christ is in cages at the border,” she said.

The majority of attendees were white, but Rohr and the CAC say they are actively trying to diversify their audience, in part by recruiting more people of color as teachers. Reverend Lewis is one. Another is Dr. Barbara Holmes. Rohr quoted Holmes often that weekend. Several weeks after the conference, I read her book Joy Unspeakable: Contemplative Practices of the Black Church, and I was particularly struck by her phrase “crisis contemplation,” especially in the context of black religious experience. The contemplative experience, she writes, has always been part of African-American religious life, often hidden in plain sight. Holmes writes of the civil-rights movement, in which she was an active participant: “You cannot face German shepherds and fire hoses with your own resources; there must be God and stillness at the very center of your being. Otherwise, you will spiral into the violence that threatens you.”

I was seated at a table with Chris Hoke, the founder of Underground Ministries, a prisoner reentry project in Washington State. Over the years, Hoke had introduced contemplative prayer to incarcerated men, including those in solitary confinement. Sitting next to Hoke was Ray Leonardini, a retired lawyer who now teaches trauma-informed contemplation to men at Folsom State Prison in California. I asked Leonardini what drew him to contemplative practice. “The only spirituality that’s worth a damn is one that deals with our pain, our trauma,” he said. “The subconscious is where all the action is.”

Between sessions I strolled through the atrium. One of the welcome tables featured signs for affinity groups. cannabis users for christ stood next to sufi taoists for christ, and raised by an atheist (realized they were christ), and one that simply said canadian. Given the event’s outlier vibe, the sign for ordained roman catholic priests seemed the most incongruous, but this was after all the Universal—not the stingy, parochial—Christ conference, and it brought all types. Standing alone, as if none of the others wanted to associate with it, was a sign for trump supporters.

Talk of Trump was blessedly absent at the conference, though it seems the Donald had inadvertently boosted Rohr’s following. A number of evangelicals turned to Rohr’s teachings following the 2016 presidential election, in which 81 percent of their fellow churchgoers had voted for Trump. My friend Hoke told me of his own vocational crisis following the election. He grew up evangelical, and though he’d long ago opted out of that tribe, his work as a prison chaplain in Washington’s Skagit Valley involved partnering with local churches, most of them evangelical or mainline Protestant. He remembers driving across Washington soon after the election, in the dead of winter, listening to a podcast debunking the myth of the nose-holding voter. Evangelicals didn’t vote for Trump reluctantly, a study showed; they supported each promise of his campaign platform. Hoke was irate. “I thought, What the fuck am I doing working with these churches?” he told me. “I felt so betrayed. I don’t want to be the judge of anyone’s heart, but anthropologically speaking, these peoples’ values were not recognizably Christian.”

After working through his initial anger, Hoke reconsidered. He realized that he made allowance for guys in prison all the time. What if churches were just boxes of people, like prisons? he thought. Some people inside them might be connected with Jesus, others not. Hoke still had access to these boxes of church people, just as he had access to boxes of incarcerated men. Following that realization, Hoke began connecting parishioners and prisoners through letter writing and a shared contemplative practice. “Jesus called people out of both the temple and the tombs. He called both into his movement,” Hoke told me. “That’s how I’ve come to understand the word ‘church’ now: ekklesia, or public assembly, might better be translated as ‘movement.’ Maybe this very connecting of religious folks and the most repressed in society is my part in that movement: a larger spiritual reorganizing of human relationships that breaks down walls between us and them, the inside and the outside, the living and the socially dead. That’s what Jesus is doing in every version of the Gospels: breaking down barriers. My contemplative journey is to open both boxes and discover that we’ve needed each other.”

Hoke’s idea of the church as movement was in some ways what the conference was about. Though initially it felt a bit fringe, my experience over the course of the weekend began to deepen. More than the plenary sessions, I came to look forward to our times of contemplative prayer, when all two thousand of us would sit in silence for ten minutes. And not a polite silence. I mean the kind in which you sit long enough to become vulnerable, when you feel on the cusp of hearing something necessary that might otherwise pass you by. Rohr and Lewis led these sessions, sometimes solo, often together, and their gentle manner onstage set a tone that invited us to attend, if only for a few brief moments, to something quiet and ancient and true.

On Monday, after the conference had ended, I spoke with Rohr in his book-lined adobe office at the CAC headquarters. He wore a full gray beard, a plaid shirt, and jeans. I found him avuncular and easygoing, if a bit worn out from the event. Over the weekend, I’d heard attendees use the words “mysticism” and “contemplation” interchangeably. I was curious to hear Rohr describe the difference.

“My definition for mysticism,” Rohr said, “is experiential knowledge of the Holy, the transcendent, the divine, God—if you want to use that word, but I’m not tied to it.” Experiential knowledge, which differs from textbook knowledge, “will always be spoken humbly, because true spiritual knowledge is always partial. You know you don’t know the whole mystery. But even one little peek into one little corner of the mystery is more than enough.”

Rohr’s experiential knowledge of the Holy came one summer evening at age ten. While visiting his cousin’s farm in western Kansas, he lay on a little patch of velvety grass hidden behind some chokecherry bushes. He was there alone, just looking up at the stars, when he felt the world open up. “It doesn’t sound very original at all,” he said and laughed, “but I knew the world was good, that I was good, and that I somehow belonged to that good world. It was what the Buddhists would call waking up, overcoming your separateness.” He had no words for it as a ten-year-old boy, but he credits the experience with giving him the psychic self-confidence that would later carry him through thirteen years of formation, the training in theology and philosophy required to become a Franciscan priest.

One of Rohr’s main projects is to move his fellow Christians away from dualistic either-or thinking and point them toward a more expansive faith that he calls the contemplative mind, or as the early Christians called it, contemplatio.

Though one could cite the Gospels, which report Jesus going frequently up a mountain to pray alone, Rohr’s brief history of contemplatio starts among the fourth-century desert fathers and mothers. Rohr can’t prove this, but he thinks the early monks began to speak of contemplatio instead of oratio—the word for spoken prayer—because oratio had been co-opted by Constantine’s Christian empire. Prayer became “a formulaic repetition of telling God things or announcing to God your grandma was sick, which is nice, but even Jesus tells us, ‘Why do you tell God what God already knows?’ ”

“That sounds like the juswanna prayer,” I said. In my evangelical church growing up, I explained, the pastor would scrunch his eyes shut and say, “We juswanna thank you, Lord, we juswanna ask you,” a curious form of address that, even as a child, struck me less as an intimate connection with God than a kind of inane virtue signaling. Rohr gave a deep belly laugh and winced. “But it’s so sincere, isn’t it? God must be so patient to put up with that.”

As Rohr tells it, the contemplative mind went underground during the Protestant Reformation. It was still being taught in some monasteries as late as the fifteenth century, and in isolated places such as Spain there was “an explosion of contemplation” through the mystical writings of Teresa of Ávila and St. John of the Cross. But then came Luther’s sola scriptura and Descartes’s cogito ergo sum, both of which placed the dualistic, egoistic mind at the center. Guigo the Carthusian, a twelfth-century monk, spoke of three levels of prayer: oratio, or spoken prayer; meditatio, using the mind to reflect on a piece of scripture; and contemplatio, the wordless prayer of the heart. This is the moment, Rohr explains, when “you shed the mind as the primary receiver station. You stop reflecting. You stop critiquing or analyzing. You let the moment be what it is, as it is, all that it is. That takes a lot of surrender.” After the Enlightenment and its Cartesian dualisms, the contemplative mind—“our unique access point to God,” as Rohr describes it—“was pretty well lost.”

It was through the writings of Thomas Merton, Rohr believes, that the contemplative mind resurfaced. On the wall of Rohr’s office hangs a framed cover of Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain, first published in 1948, a story about a bohemian artist turned monk. When I later asked Rohr how he came by the first-edition cover, he said, “I stole it.” In 1985, he spent a forty-day Lenten retreat at Merton’s hermitage. On the floor he noticed a dusty stack of books written by Merton, and he realized they were the author’s personal copies. “I said, ‘Who’s going to care, nobody will even notice’—this is how I justified it at the time,” Rohr told me, and laughed. After ripping off the cover, he framed it in glass. On the back he wrote, “May God forgive me for this holy thievery.” The original hardcover edition sold six hundred thousand copies, helping to launch what Rohr sees as the beginning of the contemplative revival. Contemplation, for Merton, was not the esoteric practice of monks—it was part of the human inheritance. In New Seeds of Contemplation, he described it as

the highest expression of man’s intellectual and spiritual life. It is that life itself, fully awake, fully active, fully aware that it is alive. It is spiritual wonder. It is spontaneous awe at the sacredness of life, of being.

So many of the mistakes in American Christianity, Rohr told me, are a result of dualistic thinking, which is “inherently antagonistic, inherently competitive. You’re forced within the first nanosecond to take sides. Republican-Democrat, black-white, gay-straight . . . go down the whole list of what’s tearing us apart—the dualistic mind always chooses sides.” He is sympathetic to those who disaffiliate from religion. But he still believes in faith’s power to instill awe, to bind and heal, to return us to ourselves, to God, and to one another. At the center of that return lies the contemplative mind.

If religio arises from the human desire to re-ligament our fractured lives, then something was on offer at the Center for Action and Contemplation that people weren’t finding in church. I wanted to know what.

Michael Poffenberger, CAC’s executive director, described the growing interest in the group’s work: “The same kind of spiritual hunger and desire to belong to a community that drove previous generations’ religious development—that still very much exists,” he said. We’ve reached what he calls “peak cynicism” about institutional faith. “But it’s also peak searching for something else—something that can be a healthier container to hold our longing for the transcendent. It’s searching for the path of transformation and service, but without the no-longer-viable parochial attitudes of past generations.”

At age thirty-seven, Poffenberger brings a certain youthful energy to the role. He also brings a political savvy honed during ten years working for Resolve, an advocacy group that helps former child soldiers in Africa. He’s now trying to think strategically about how the CAC can serve a movement. People looking for contemplative spirituality outside traditional religious structures can join the Spiritual But Not Religious demographic, or take up mindfulness meditation, or explore Buddhism, but there are no clear on-ramps for contemplative Christianity.

“We’re in the first generation of trying to unpack and make accessible the contemplative dimensions of Christianity,” Poffenberger told me, “but we’re two generations behind the Buddhists, who brought their wisdom to America from the East. Buddhism is spirituality that actually works. It supports those mechanisms that actually change the chemistry of the brain and lead to a transformed embodiment in the world, as neuroscience is starting to show.” Rohr and Poffenberger hope to convince Christians that they don’t have to leave Christianity to find contemplative depth; it has been part of the tradition all along.

In the months following the conference, I was reminded of just how far American Christianity has strayed from anything close to a focus on interiority, which is perhaps why Rohr’s work has attracted so many of those leaving Christendom.

I count myself among the defectors. Though I grew up as a missionary kid, have a master’s degree in theology, and teach at a prominent divinity school, I have more or less stopped going to church. The pandemic has provided an easy out, of course. Since March, it hasn’t been possible to attend church if I wanted to. But I find myself not wanting to go back, at least not to church as I’ve known it: an institution weighed down by a thousand cultural accretions. The parish subcommittees. The lackluster preaching that hinges on lame sports metaphors. The insufferable blandness. None of it seemed to be leading me any closer to what I really craved. Which was what? That was harder to name.

In describing qualities of certain saints, William James, in The Varieties of Religious Experience, articulates my list of hungers: “Religious rapture, moral enthusiasm, ontological wonder, cosmic emotion.” He explains that “all [are] unifying states of mind, in which the sand and grit of the selfhood incline to disappear, and tenderness to rule.” Those unifying states of mind spoke to me, though I had no interest in losing my sand and grit; from my reading of the Christian mystics, contemplative prayer gives one more grit, not less. One of the mystics I loved reading was the seventh-century hermit St. Isaac of Syria, who was an inspiration for Dostoevsky’s Father Zosima, and who wrote this:

If you love the truth, love silence; it will make you illumined in God like the sun, and will deliver you from the illusions of ignorance. Silence unites you to God Himself.

And this: “Let the scale of mercy always be preponderant within you, until you perceive in yourself that mercy which God has for the world.”

I was also reading Cassian’s Conferences and considering the author’s role as chronicler of the early Christian monastic movement in Egypt, a kind of fifth-century immersion journalist of the soul. Cassian describes Christian life as a journey toward puritas cordis: purity of heart. If that is the destination, the vehicle is silent prayer.

Ontological wonder, tenderness, puritas cordis, pondering scales of mercy: these seemed like activities worthy of my meager efforts, and I felt a similar hunger for those things among other contemplatives, those who were also leaving the barnacled, empty supertanker of Christendom and boarding smaller, more nimble vessels.

“Does mysticism need a church?” In his introduction to the Conferences, the Cambridge historian Owen Chadwick poses this as a central conundrum in early monastic thought, a question that was very much alive among the modern contemplatives. “The individual experience of the divine is overwhelming,” Chadwick writes. “It passes beyond the memory of biblical texts and every other thought. . . . Might it be that holy anarchy is nearer to God than ordered ecclesiasticism?”

Like Cassian, I was more drawn to holy anarchy. And yet, in the process of fleeing broken ecclesial institutions, didn’t the new contemplatives also constitute a body politic? What was the Universal Christ conference if not a new form of church? It’s possible to see organized religion as a necessary evil, something that could be dispensed with once individuals reach some higher plane of awareness, but that seems facile. Humans depend on patterns and structures. Forms change, but we still need them to provide some kind of continuity of thought and praxis, just as we depend on forms to build community, which is the other piece missing in the laissez-faire approach. In an essay titled “The Mystical Core of Organized Religion,” the Benedictine monk Brother David Steindl-Rast readily acknowledges that “mysticism clashes with the institution.” And yet, he admits, “We need religious institutions. If they weren’t there, we would create them. Life creates structures.”

In the months following the conference, I wondered how all the new contemplatives would continue their practice without a community, how they would avoid falling into that American DIY approach to spirituality that so often amounts to just making shit up.

Perhaps the question is not whether mysticism needs a church, I thought, but whether mysticism can reach its full potential without one. I found this question embodied by a man named Adam Bucko.

On a rainy Monday night in November 2019, a purple school bus adorned with white unicorns pulled into the parking lot of the Hempstead Transit Center on Long Island. Ella Fitzgerald crooned softly on the radio. Reverend Bucko, director of the newly formed Center for Spiritual Imagination, was leading a group of students from Adelphi University on a service trip, and he had invited me along. The group had picked up a load of sandwiches from Adelphi’s food court and planned to spend the evening cruising the streets of Hempstead looking for hungry people. Now, just before everyone disembarked, Bucko asked us to pause and close our eyes.

“Mother Jesus,” he said, “we bring all our anxieties, our hopes, our dreams, and ask you to hold them. Give us courage.” In Bucko’s slight Polish accent, the last word rhymed with porridge.

During the time I spent with Bucko, I was struck by the way he often used feminine language for God, borrowing from mystics such as Julian of Norwich, a fourteenth-century English mystic who also spoke of “Mother Jesus.” Long-dead saints like Julian are for Bucko quite alive. He grew up in Communist Poland, and remembers a moment in 1985 when he was kneeling and praying with his mother and father before an icon of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, a nineteenth-century French mystic, before his father fled to America. “The Poland of my childhood was a place of violence and tragedy,” he writes in a short introduction to Holy Thirst, a book on Carmelite spirituality. “Saints like Thérèse, and the many miraculous stories of their presence among us, made us feel stronger than the violence of the state.” Since his childhood, he has been drawn to the archetype of the priest. For him, priests were heroes who resisted the Communist regime. Among them was Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, a Gandhi-like figure who encouraged nonviolent resistance and was killed by the state. Bucko remembers seeing his broken body shown on live TV. Father Suchowolec, the priest in the parish where Bucko was baptized, was also killed. These deaths had a profound effect on Bucko, leaving him with lasting trauma. Even as a six-year-old, he collected anti-government flyers. After Father Suchowolec’s death in a fire connected to the regime, he hid under the blankets in his bed, convinced they were “coming for me next.” Faith and resistance were part of his DNA.

With ankle-length dreadlocks and tattered jeans, Bucko does not look like an Episcopal priest. Listening to him describe his background in Polish anarchist and Rasta-punk movements is confusing at first, because he exudes such warmth and gentleness. One minute he’s praying to Mother Jesus, or speaking in rapturous tones about a certain Sufi mystic, or talking about the power of the Eucharist, which he refers to as “Christian shamanic technology,” and the next he’s gushing about reggae, a love I happen to share. The various text messages I received from him before and after my visit included incense-clouded photos and YouTube links to Alpha Blondy, Ijahman Levi, and Misty in Roots, as well as a 1989 anti-apartheid reggae concert at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk.

Before he became an Episcopal priest, Bucko was a sort of itinerant preacher, leading retreats for young activists who identified as Spiritual But Not Religious, teaching ideas he later described in two co-written books, Occupy Spirituality and The New Monasticism. He also spent fifteen years working in Manhattan with homeless kids, many of them queer people of color. “I don’t know how to explain this,” Bucko told me, “but for much of my life I’ve been carrying in my body somebody else’s pain. When I met a group of street kids, I realized it was theirs. I’ve been to lots of monasteries, but it was only when I started working with homeless kids that I discovered what contemplative prayer means. How to help people hold their pain, and underneath that find a presence we can say yes to.”

To provide a kind of family for these kids, Bucko co-founded the Reciprocity Foundation, an organization that combines contemplative practices with instruction in life skills. That’s where he learned how to pray. Instead of trying to solve the homeless kids’ problems, he would simply sit with them in a state of receptive listening. “We didn’t start with theories,” Bucko told me. “We started with their heartbreaks. We started with things that make them come alive.” He acted as both companion and guide on these inner journeys, helping teens pay attention to “the impulse of God.” Listening for that impulse, and discerning the meaning of it, is for Bucko what contemplative practice is all about. This is what he calls his methodology of prayer.

That night on the bus, we sat quietly in the darkness of the parking lot. Rain beat down on the metal roof. Occasionally Bucko would offer a suggestive word or phrase, part of his guided-meditation style, but mostly we sat in silence. Then we filed off the bus and delivered sandwiches.

The next night, I joined Bucko for a contemplative prayer service he leads at the Cathedral of the Incarnation in Garden City. The weekly service is one of a number of new offerings by the Center for Spiritual Imagination, a “new monastic” community that aims to, as Bucko says, “take the best of Christian monastic traditions and translate them into an engaged path of contemplation and justice for those who no longer feel at home in the church.”

To shrink the space of the otherwise cavernous cathedral, Bucko had arranged a semicircle of several dozen chairs in front of the altar. On a dais stood a large icon of Mary, surrounded by scores of candles. Before everyone arrived, Bucko rearranged his dreads, which he keeps in a bun, and began lighting the candles.

I sat next to Sister Alison McCrary, a friend of Bucko’s. McCrary was for many years a nun with the Sisters for Christian Community, a noncanonical Catholic order of religious women formed after the Second Vatican Council. She now describes herself as “a social-justice-movement lawyer and restorative-justice practitioner.” She is also a member of the United Cherokee AniYunWiYa Nation. When we met for coffee earlier that day, McCrary told me about her work in what she calls contemplative resistance: providing food and shelter for ICE detainees, offering pro bono legal services to people living in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, counseling men on death row at Angola, and teaching at the School for Contemplative Living in New Orleans. I told her she didn’t seem like the stereotypical contemplative who withdraws from society. The popular view of religious contemplation, she said, treats it as a form of “self-care,” like going to the gym. “It’s not about other people, not about the common good, it’s not about the poor and the marginalized. But that’s what the Gospels are about. I don’t think you can have contemplation without action, and you can’t have action without contemplation.” Each morning she spends thirty minutes sitting in silence, which she describes as an act of “one-ing” with God. “It doesn’t happen every time I sit with God. But ideally I’m noticing God’s movements, being aware of them.”

Soon the darkness of the cathedral was filled with dozens of flickering candles. People trickled in, taking seats first in the semicircle and then farther back in the pews, perhaps one hundred attendees in total.

At seven o’clock, Bucko rang a singing bowl to begin. Speaking softly into a microphone, he invited us to find a comfortable position, our feet touching the ground, and take a couple of deep breaths. “Breathing in, breathing out,” he instructed, making his own breath audible.

Silence descended.

After a time, Bucko offered a spoken prayer: “Mother God. We don’t know the words. We don’t know the way. We know you are a quiet God. Help us to listen to your voice in this noisy world of our minds. We want to be with you. We want to experience your peace. Help us to truly taste your presence right now.”

Slowly, over the next half hour, Bucko continued this guided meditation, punctuated by emphatic stretches of silence.

“Where does pain live in your body?” he asked. “Your disappointments? The things you’re too ashamed to name? And your joys, hopes, and longings—where do they live?”

In the silence, I had a feeling that I was at once sinking into something and also being lifted up. Bucko asked us to imagine bringing all our emotions into our hearts, to envision them traveling through our bodies to reach it, to place the palms of our hands on our hearts, holding our emotions with tenderness and care, “as if you were holding a little baby, with that kind of love and curiosity. Remember that you are sitting in the presence of God and that God is there with you. Is there anything you want to say to God?”

I don’t know how long it lasted, but I was still sitting with my hands on my heart when Bucko rang the singing bowl again. It was time for silent walking meditation. I found myself disoriented, perhaps from the blurry, slow-motion forms moving around me in the flickering dark, like people walking underwater, or perhaps from a sudden upwelling of emotion. When a small alcove presented itself over in the left transept, I slowly made my way in that direction. From somewhere in the darkness, a lone female cantor began to sing. It was the Jesus Prayer: Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner, except the words were sung in a foreign tongue—Ukrainian, Bucko later told me—a beautiful refrain sung over and over, insistent in its yearning.

In the alcove, a single candle burned, unadorned. As I stood before the light, a strange melody echoing around me, I tried to listen. When Jesus taught his disciples how to pray, he told them to go into their inner room, to pray to God in secret. I thought of Abba Isaac’s words to Cassian: that God “will be all that we think about, all our living, all that we talk about, our very breath.” If I heard something in that moment, it would be glib to repeat here. I was moved, yes. But standing there alone, my back to the others, I also came to feel that my solitude was not a point of arrival.

In his book Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, Merton describes an incident he experienced in Louisville, Kentucky, on March 18, 1958, as he stood on the corner of 4th and Walnut Streets.

“There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun,” he writes.

I suddenly saw the secret beauty of their hearts, the depths of their hearts where neither sin nor desire nor self-knowledge can reach, the core of their reality, the person that each one is in God’s eyes . . . It is like a pure diamond, blazing with the invisible light of heaven . . . I have no program for this seeing. It is only given. But the gate of heaven is everywhere.

It is striking that Merton’s epiphany occurred not in a monk’s cell or cathedral alcove, but on a busy street in Louisville. Sartre famously said that “hell is other people,” but for Merton, and for Holmes, Bucko, McCrary, Rohr, and so many of the contemplatives I met, other people are not hell; they are portals to paradise.

One paradox of the contemplative life is the way in which it engenders, even demands, participation in a community. “The life of a Christian is not a solo act,” McCrary told me. “Jesus went to the desert alone to pray, but he was always building community. It’s a both-and.” The reverse is also true. Rohr: “How you relate to your spouse, your children, your dog—that’s how you’ll relate to God.”

The gate of heaven opens for us all, but the hinge swings outward as much as inward, leading not into some hermetically sealed chamber, but a spacious meadow where we find every person we’ve ever known, a field of solitaries loved beyond measure, a destination as near as our next breath.

Somewhere behind me a bell rang. The blurred forms moved again in the candlelight, returning to their seats before the altar. I left the alcove and joined them.