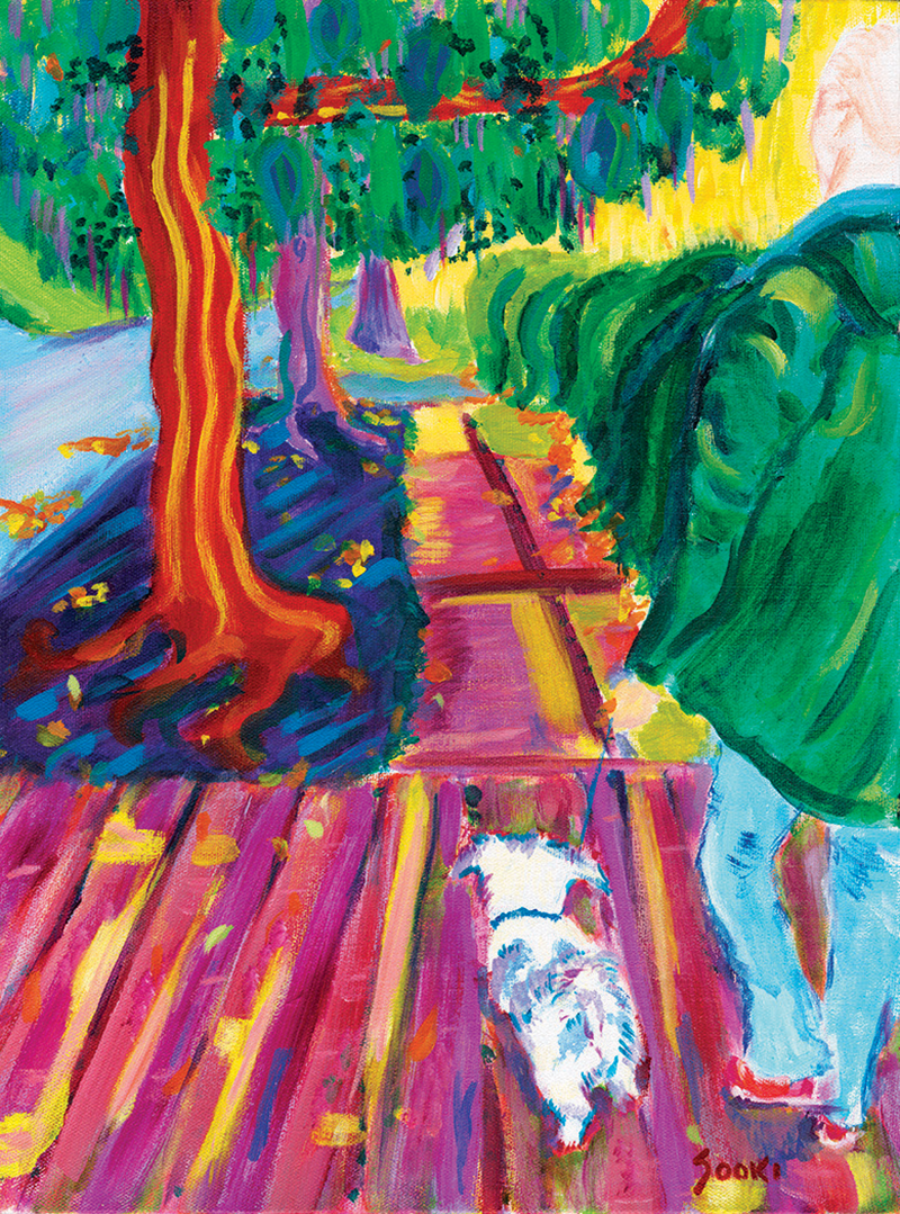

Paintings by Sooki Raphael. Sparky Walks the Neighborhood with Ann, Nashville 2020

I can tell you where it all started because I remember the moment exactly. It was late and I’d just finished the novel I’d been reading. A few more pages would send me off to sleep, so I went in search of a short story. They aren’t hard to come by around here; my office is made up of piles of books, mostly advance-reader copies that have been sent to me in hopes I’ll write a quote for the jacket. They arrive daily in padded mailers—novels, memoirs, essays, histories—things I never requested and in most cases will…