The Business of Scenery

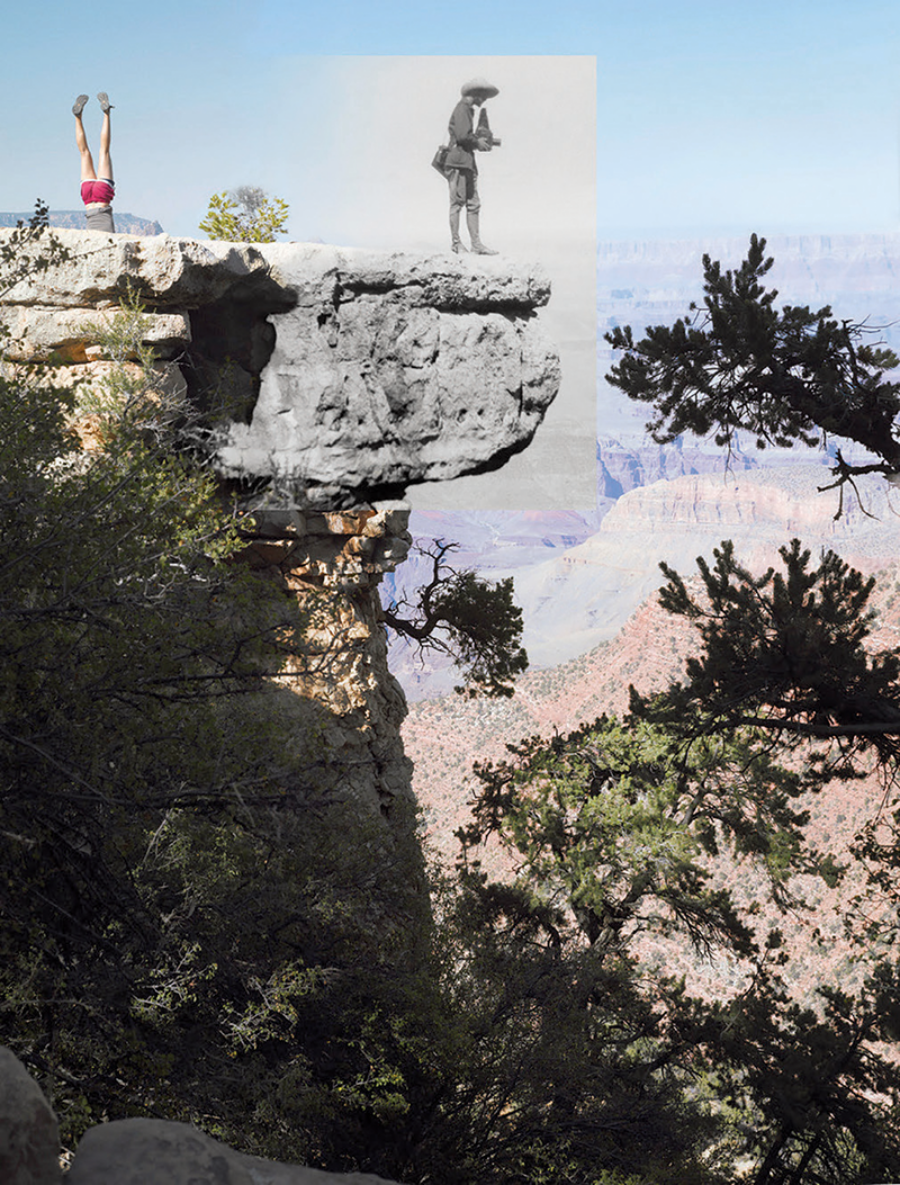

“Woman on head and photographer with camera; unknown dancer and Alvin Langdon Coburn at Grand View Point, 2009,” by Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe. Courtesy Etherton Gallery, Tucson, Arizona. Inset: Photograph by Fannie E. Coburn, c. 1911. Courtesy George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York

“If you love a place,” a retired ranger who worked at the Grand Canyon once told me, “don’t make it a national park.” On a typical visit to Grand Canyon National Park during the summer, you will first find yourself stuck in traffic backed up a mile or more from the entrances, the idling cars belching fumes. When at last you snag a parking spot and, with everyone else, debouch onto the hiking trails, you’ll find food wrappers, toilet paper, discarded clothing, and plastic bottles, courtesy of the previous blast of visitors. You will experience, alongside the glorious vistas, your fair share of the stink of human feces and, at choice spots for taking a piss, the piercing ammonia perfume of urea.

Wallace Stegner called the national parks our “best idea,” but one wonders these days about the greatness of the National Park Service, which, since the moment of its inception, has done nothing but encourage the human tide. The 1916 National Park Service Organic Act, which established the agency, tasked it with conservation of “the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life” in parks. It also directed the NPS, however, “to provide for the enjoyment” by the public of these same protected lands. Congress perhaps didn’t imagine a time when this dual mandate would pose a contradiction, when visitation might threaten conservation.

Today, the parks are smothered with visitors. In 1919, three years after the NPS was established, it welcomed 781,000 people across the country. In 2019, the total rose above 327 million. In the ten most visited parks—Grand Canyon is number two, behind Great Smoky Mountains—there is tension and stress and social conflict from overcrowding. In Yellowstone, our oldest national park, high-speed motorists intent on viewing as much of the landscape in as short a time as possible pass one another in daring maneuvers that portend disastrous collisions. Between 2014 and 2016, there was a 90 percent increase in car accidents in Yellowstone and a 60 percent increase in ambulance use. During that same two-year period, the park has documented increasingly widespread soil erosion and vegetative trampling from foot and auto traffic. In Glacier National Park, fistfights have erupted over parking spaces, with one driver going so far as to ram into people attempting to hold spots. In Zion National Park, crowding is such that one of the most popular trails had to be temporarily closed in 2017 to airlift eight tons of human excrement from public outhouses that a journalist described as an “open sewer.”

Solitude and solace are two of the experiences we have come to expect from our national parks. But you won’t find either while jockeying for Instagram photos on the rim of the Grand, crushing into shuttle buses at Zion as you would into a rush-hour train in Manhattan, or pitching your tent in a packed campground in Yosemite, where by nightfall the yapping of your fellow citizens degenerates into a cacophony of children crying, couples bickering, old men snoring, and gadgets pinging. Much of the night is spent not in appreciation of the ancient sky but in despising your fellow man a bit more than usual. Such is the experience of the park system’s crown jewels circa 2021. If this is what the parks offer, then maybe we need to rethink the system altogether.

Robert Sterling Yard, a journalist who served as publicity director at the Park Service from its founding until 1919, saw immediately that his work to educate Americans about the park system threatened to devolve into what he called, with undisguised contempt, “recreational super-promotion.” Increasingly alienated from the agency for his discordant views, Yard warned that the NPS was headed into “the business of scenery.” In a 1926 essay, he concluded that the primary threats to the park system came from three sources:

(1) From industrial companies that want to use the parks for profit; (2) from communities which want to attract profitable motor crowds by offering local national parks developed and maintained at the expense of the national government; and (3) [from] enthusiasts for unlimited recreational expansion . . .

Yard worried that business interests would transform the parks into mere economic engines, with little regard for what he called “wilderness values.” This would lead to industrialization, to more roads and more facilities. “Before the National Parks System can be completed, and turned to its highest usefulness,” he wrote, “it must be saved from those, who, out of mistaken conceptions of plans and purpose, would reduce it to the general level of the country’s playgrounds.”

Fast-forward to 1958, by which time Yard’s remonstrance had long been forgotten. Congress convened the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission, which included both outdoor business interests and conservationists, to tabulate how much money parks were bringing in. The commission, finding that parks were already a powerful machine whose operations henceforth needed to be maximized, advised the Department of the Interior, overseer of the National Park Service, to expand its advertising operation. It envisioned a new line of commercial activity in the parks, particularly for the pleasure of the motoring public: partnerships with the tourism industry in which for-profit concessionaires, as well as restaurants, hotels, bars, and trinket shops, would operate inside park boundaries.

With this model of vehicular tourism and the provision of bountiful amenities, the Park Service has enjoyed incredible success—if success is defined narrowly as the number of people willing to spend money for the privilege of squeezing into the public lands it manages. This money not only benefits the parks themselves but also finds its way into surrounding communities and towns. The NPS proudly reports that recreationists from every U.S. state and scores of countries now spend tens of billions of dollars annually in these “local gateway regions.” Some 329,000 jobs nationwide depend on maintaining the flow of people into the parks, a figure well known to the higher-ups in the Park Service bureaucracy.

Even as the number of visitors has reached record highs, however, the morale of Park Service employees has hit a record low. According to the annual Best Places to Work in the Federal Government survey, which ranks 420 agencies, the Park Service fell from 130th in 2006 to 320th in 2019. By then, morale at the Park Service was lower than at all but one of the agencies in the Department of the Interior: the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The reasons why rank-and-file Park Service employees feel so bad about their jobs are numerous. They are poorly paid; their housing is substandard. Many parks are understaffed in addition to being overrun, and congressional appropriations for the agency have not risen in tandem with the addition of new parks or the rise in visitation. Moreover, the culture of the Park Service has been, and remains, rampant with sexual harassment and bullying. But in my regular conversations with employees, I found that the principal reason they feel adrift has little to do with material conditions or social justice. The core problem is that the Park Service no longer offers any animating heroic vision of protecting the natural world.

Frank Buono, who worked for the Park Service for twenty-five years, from 1972 to 1997, and for another twenty years as an instructor at the agency’s training centers, told me that the last conservationists in the vein of Robert Sterling Yard had been excised over the past two decades. The recreation zealots, long dominant within the agency but stymied by recalcitrant personnel, emerged triumphant. “The old generation of strict conservationist managers have been replaced with a new type of manager who is more comfortable at cocktail parties with Coca-Cola,” Buono told me.

In 2016, the nonprofit Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) conducted a survey to determine which parks had produced general management plans. These plans—which were mandated under the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978—were required to include both “measures for the preservation of the area’s resources” and “implementation commitments for visitor carrying capacities.” PEER surveyed fifty-nine national parks, nineteen national preserves, eighteen national recreation areas, two national reserves, and ten national seashores—a total of one hundred and eight sites—and found that only fifty-one had produced the required plans. Today, of those fifty-one units, none have set limits on visitation, as the 1978 law required. Of the ten most visited national parks, seven—including Grand Canyon and Yellowstone—have no management plan at all. Lawmakers have never bothered to hold the agency to account. Commenting on PEER’s report, Jeff Ruch, then the group’s executive director, noted that the 2016 Find Your Park campaign, designed to promote the NPS’s centennial and increase visitation, came on the heels of the news that more than fifty national parks had broken their visitor records the previous year. “Instead of ‘Find Your Park,’ ” Ruch quipped, “the challenge should be called ‘Find a Place to Park.’ ”

Such a state of affairs is perfectly acceptable to the recreation-industrial complex. According to estimates from one industry group, outdoor recreation injects as much as $778 billion into the U.S. economy, almost twice as much as the pharmaceutical industry. The most articulate and connected spokesperson for this outdoor capitalist machine is a sixty-nine-year-old snowmobile enthusiast named Derrick Crandall, who got his start in the Seventies as an advocate for snowmobile access in Yellowstone’s backcountry. Thanks largely to his efforts, snowmobiles, which wreak havoc on wildlife populations, are now a daily fact of life in the Yellowstone winter.

Crandall is best known, however, for his long tenure as president and CEO of the American Recreation Coalition (ARC), a lobbying outfit, which, at its inception in 1979, consisted of dozens of corporations and trade groups, including Chevron, Exxon, and the American Petroleum Institute; automobile and recreational vehicle manufacturers; hotel and restaurant consortiums; and gear and clothing distributors and retailers. During his time at ARC, Crandall testified in Congress on multiple occasions in support of opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling, fought fuel-economy standards on behalf of automakers, and worked closely with groups tied to the astroturf “wise use movement,” a front for fossil-fuel interests. He was so close with Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush that he took each of them on personalized recreational adventures.

The intention of the American Recreation Coalition—which in 2018 was reorganized into the Outdoor Recreation Roundtable (ORR)—was to package national parks and other public lands as a value-added product, with experience of the natural world rendered as a commodity for sale, like a visit to Disneyland. (The Walt Disney Corporation was among ARC’s more enthusiastic members.) The ORR’s priorities were clear: no limits on visitation, more fossil fuels burned, more consumer items purchased (especially cars and campers), and more stays at hotels and campgrounds. The premise was that nature is best appreciated by those willing to lay down the most cash.

This idea has unified an army of acronyms in the industry. Crandall’s ORR includes groups such as the NMMA (the National Marine Manufacturers Association, which represents the $42 billion boating industry), the RVIA (the RV Industry Association, with a proclaimed $114 billion in “economic impact” from RVers), and the OIA (the Outdoor Industry Association, which, as the most influential trade group in the sector, represents thousands of other outdoor interests, including putatively conservationist corporations such as Patagonia, REI, Kelty, and the North Face). So incestuous are these relations that an executive at OIA replaced Crandall as the director of the ORR after he retired from that position in 2019; the president of the NMMA, who also serves as the vice chairman of the board of ORR, was formerly the president of the RVIA.

The outdoor capitalists were all too happy to find a cooperative partner in the Trump Administration. In April 2017, a month into the tenure of Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke, recreation lobbyists met with him in Washington to discuss potential public-private partnerships. Crandall was there, alongside his old friend Frank Hugelmeyer, president of the RVIA, and Amy Roberts, executive director of the OIA, who would go on to a senior position at the North Face.

The next year, Crandall was appointed co-chair of the Outdoor Recreation Advisory Committee (ORAC), the presidential commission formed to counsel the National Park Service on “public-private partnerships across all public lands,” which consisted almost entirely of representatives from the recreation industry. The committee’s final report proposed a series of reforms: campgrounds should be privatized, visitors should pay higher fees, and more services should be run by for-profit concessionaires. It so happens that numerous members of ORAC—among them the CEO of Delaware North and the president of Aramark Leisure, both concessionaires operating in the national parks—served commercial interests that would have benefited financially from the changes. Only after it was exposed in the press and denounced in an outpouring of public concern was ORAC dissolved and its privatization program abandoned.

Though we now have a new administration pandering to environmental groups with nice-sounding ideas, such as conserving 30 percent of the country’s landmass by 2030, there is no indication from the Democrats that the recreational juggernaut will face real resistance any time soon.

“Don’t believe for a minute that everything was wonderful under Obama, Salazar, and Jarvis,” said Buono, who voted twice for Obama. “I hear people from the retirees group, the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks, say that under Trump we have been living in hell but under Obama we were in heaven. The effect is to create a completely false understanding of history that says if you vote a certain way—for the Democratic Party—all will be fine with the parks. To be honest with you, there was more systemic damage to the park system under Obama than there has been under Trump.”

The decline in Park Service morale, in fact, was most pronounced during the Obama years. “A manager would meet approval under Obama if he raised a lot of money with public-private partnerships, took no rigid stance on conservation, sidestepped natural-resource issues such as ecological harm from development and visitation, and advocated for more and varied recreational activities,” said Buono.

Of the corrosive accomplishments at the Park Service under Obama, it suffices to mention just a few. As PEER has documented, the NPS director, Jon Jarvis, working in concert with Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar, opened parts of Big Cypress National Preserve to swamp buggies, permitted the use of Jet Skis at national seashores and lakeshores, and pushed for new mountain-biking trails in backcountry areas. But they did more than merely promote destructive recreation. Jarvis and Salazar also stalled wilderness designations for tens of thousands of acres (despite the fact that such designations are the most effective way to protect biodiversity); moved to open parks to corporate branding partnerships; deregulated parks for bioprospecting, in which the NPS would profit from consumer products developed from enzymes, bacteria, and other microorganisms collected within park boundaries; and reversed a plan to ban the sale of plastic water bottles in most national parks, following pressure from Coca-Cola and other bottled-water companies. By the time Obama left office, PEER reported that “our national park system is in far worse shape today than eight years ago.”

“Sixty-six years after Edward Weston’s ‘Storm, Arizona’ from Marble Canyon Trading Post, 2007,” by Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe © The artists. Courtesy Etherton Gallery. Inset from 1941. Courtesy the Center for Creative Photography, Tucson

If the NPS cared a whit about ecological harmony in the age of climate change, it would end the profit-driven practices that reduce ecosystems to a carbon-intensive scenic and experiential commodity. If the NPS cared that large crowds terrorize and kill wildlife—in the latter case, mostly with cars—it would set capacity limits. If the NPS cared that maximizing use produces anxiety, hurry, and worry among the visitors themselves, it would do the same. But the overwhelming trend in the Park Service’s one hundred years has been precisely the opposite: more recreation, more people.

The vast majority of the agency’s budget goes toward fueling this growth. The Park Service plaintively cries that it suffers from a nearly $12 billion budget shortfall and that Congress has starved its bureaucracy, preventing its noble servants from achieving greatness. But as for that maintenance deferred: more than half of the agency’s deficit, $6.15 billion, is earmarked for maintaining bridges, tunnels, parking lots, and paved roadways, so that more drivers can sit in traffic. Less than $1 billion is allocated for the upkeep of trails and campgrounds.

The agency complains about not having enough money to continue packing sardines into the can, but will not countenance the possibility of fewer sardines. It seems to stand for little else than the deranged idea that more visitation is always better. It has failed to abide by its own mission as laid out in the 1916 Organic Act, which federal courts have repeatedly upheld: conservation, with recreation permissible only so long as it does not impair the history, scenery, or wildlife being conserved. Perhaps, then, in this era of cascading ecological crises, the time has come to scrap the Park Service, to consider alternative ways of managing our public lands.

My quixotic vision is for a new federal agency, with a name befitting a new purpose. Call it the Department of Environmental Preservation, say; or the National Ecosystems Defense Agency; or, better yet, the Department of Ecological Sanity. Under this new department, concessionaires and their associated souvenir and trinket shops—parasites that have fed for far too long on the public domain—would be banned. Cars would be eliminated from parks as well, leaving roads to decay and be reclaimed by forest and desert, and consigning the $6 billion in deferred maintenance costs to irrelevance. In doing so, this new agency would also solve the problem of overcrowding, as a visit would no longer be carbon-subsidized and would be as easy (or as hard) as, well, a walk in the park.

The writer and conservationist Edward Abbey, who worked for a decade as a seasonal ranger with the Park Service, envisioned a version of this very different park system in his 1968 book Desert Solitaire. “Let the people walk,” he advised. “We have agreed not to drive our automobiles into cathedrals, concert halls, art museums . . . we should treat our national parks with the same deference, for they, too, are holy places.” Abbey was right. But where he fell short was to think that such a radical transformation of management was possible without dismantling an agency so invested in profaning sacred ground. So let’s act accordingly by abolishing the National Park Service and replacing it with something better. Let’s have parks where the public land and its wildlife are free of machines and noxious crowds. Let’s have parks where people can be free of industry.