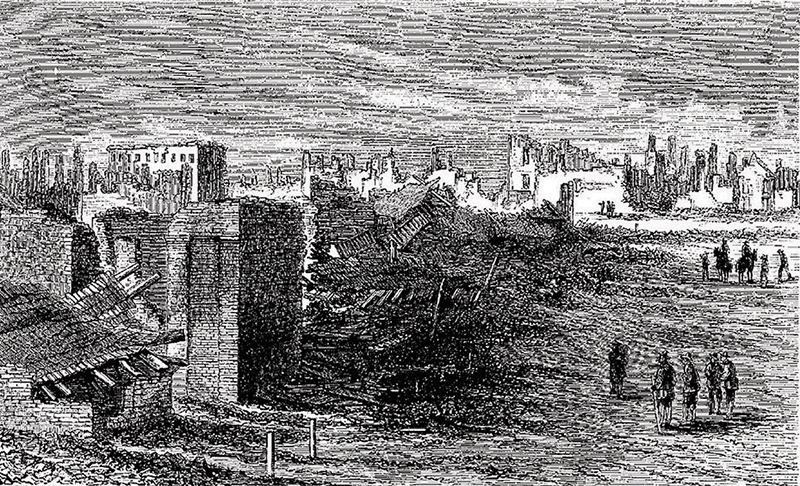

Atlanta in ruins. Originally published in the October 1865 issue of Harper’s Magazine

“You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it,” said General William Tecumseh Sherman when he ordered the whole population of Atlanta to flee wherever it desired. In Atlanta, they had not realized what war was till then.

North and south they fled, but mostly south, for they were bitter, and the roads filled with the pitiful array of thousands of men and women and children with their old-fashioned coaches, with their barrows, with their servants, with those slaves who did not heed the fact that their day of liberation had arrived. What complaints, what laments, as the proud Southern population took the road! A lamentation that is still heard today.

When the people had gone, Atlanta was set on fire. Sherman had decided to march to the sea, and he could not afford to leave an enemy population behind, nor could he allow the chance that secret arsenals might exist there after he had gone. It was a never-to-be-forgotten spectacle, “the heaven one expanse of lurid fire, the air filled with flying, burning cinders,” a soldier recalled. Small explosions arranged by the engineers were punctuated by huge explosions when hidden stores of ammunition were located, and while these added ruin to ruin in the city, they sounded as lugubrious and awful detonations to the soldiery on the road. Churches, shops, warehouses, homes—the fire flared from every story and every window.

Though the march was military, it inevitably became punitive. The cotton was destroyed, the farms pillaged, the land laid waste. It was a comparatively narrow strip of country, but Sherman was like the wrath of the Lord descending upon it.

That was in the fall of 1864. Years have passed and healed many wounds. Now it is the fall of 1919 and all Georgia is at her capital city for the fair. The automobiles are forced to a walking pace, there are so many of them, and they vent their displeasure in a multiform chorus of barking, howling, and hooting.

Atlanta’s new life has grown from the old ruins and hidden them as a young forest springs through the charred stumps of a forest fire. On each side Atlanta’s skyscrapers climb heavenward in severe lines, and where heaven should be the sky signs twinkle. Every volt that can be turned into light is being used. The stores and the cinemas are dazzling to show what they are worth. The sidewalks are thronged with Southern youth who show a camaraderie one would hardly observe in the colder North. One has the thought, however tenuous, that perhaps Atlanta did not burn in vain, that perhaps the South believes as well as the North in the immortality of John Brown’s soul. But it seems impossible that the destruction of Atlanta and the pitiful exodus of its humiliated people has been forgotten—nor, for that matter, the elation of the Northern soldiers who sang while the city burned.

Where the bloody Battle of Atlanta raged, however, a complete peace has now settled down amid the dignified Southern homes. Trees hide the view and children play upon the pleasant lawns, while the older folks rock to and fro upon the chairs of shady verandas. Dignified Decatur dwells on its hill by the wayside, where one can find its pale monument to the Confederate dead. On this white obelisk the cause of the South is justified in print. Within sight of it rises an impressive courthouse, which, by its size and grandeur, protests the strength of the law in Georgia.

As I walked along the road from village to village and from mansion to mansion, I was always on the lookout for the oldest folk along the way. The young ones knew only of the war that was just past, the middle-aged thought of the old Civil War as a sort of joke, but the old folk would never dare laugh over the strife, which amounted to the great passion of their lives. Certainly they remembered the great march, what came before and what came after.

From “Marching Through Georgia,” which appeared in the April 1920 issue of Harper’s Magazine.