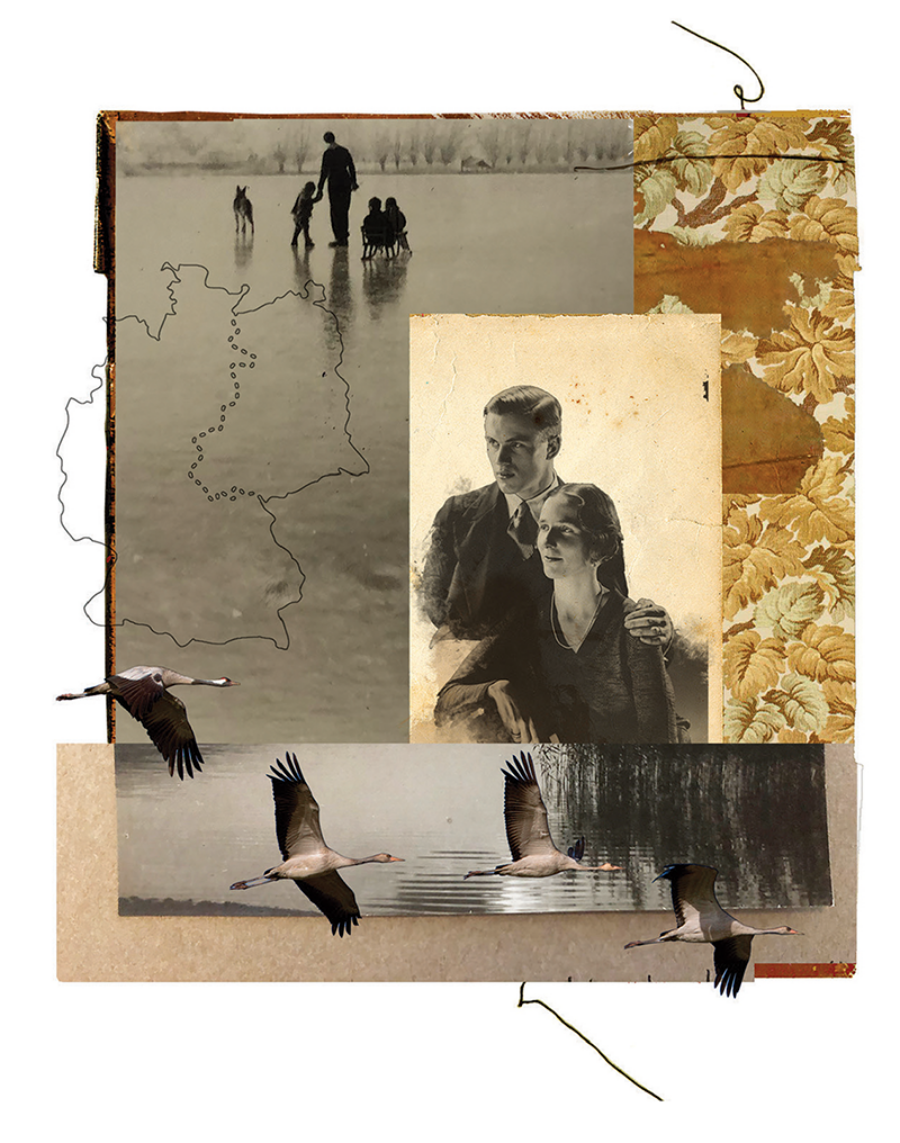

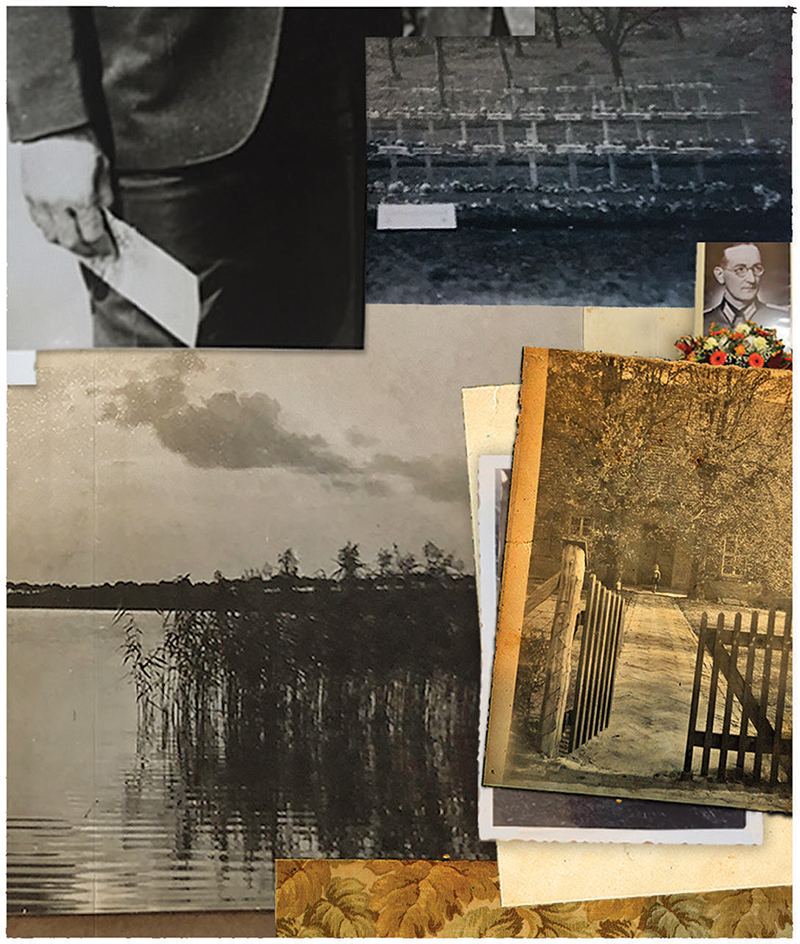

Collages by Jen Renninger. Source photographs courtesy the author. Cranes © Nature Picture Library/Alamy

November 9 has a special place in German history. In 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II’s abdication; in 1923, the crushing of the Beer Hall Putsch; in 1938, Kristallnacht. Other November ninths fill out the list, but Germans recognize a Schicksalstag, a fateful day, when they see one.

For many years I was a regular at the Frankfurt Book Fair, scouting titles for the American market. In October 1989, I heard buzz at the fair that thousands of East Germans were fleeing through Hungary’s porous border with Austria.

On November 9 of that year, the Berlin Wall was breached. Without shots or tanks, just bureaucratic confusion, the structure the Communists called the Antifascist Protective Barrier came down, and another curious and enduring battle with history began.

Back at the fair the following October, I spotted a T-shirt for sale featuring the phrase endlich: ein deutschland weniger (“Finally: one Germany less”). I’m not given to message tees, but I succumbed to this one’s cool recognition of the historic moment, its tidy encapsulation of two distinct concepts: Germany’s internal relief at reunification after a brutal separation; the rest of the world’s relief at having just one Germany to contend with. It was succinct, apposite, and funny.

It also resonated personally. My parents met in Paris in 1927. My father was the penniless scion of an aristocratic Baltic German family with a long history in Russian government that was exiled by the Bolsheviks in 1918; he was studying history and law at the Sorbonne in preparation for a diplomatic career in the service of Germany. My mother was an American debutante longing to escape her family’s suffocating expectations. They married in 1928. The Depression and then Hitler darkened their future. My father could find no work. When he went off to war in 1940, there were five children. By July 1941, another (me) was on the way, and he was dead. My mother rode out the war in Germany, then loaded the children and goods into a farm wagon just ahead of the advancing Red Army. In 1947, I arrived in the United States with my mother and one sister. It took another year for the rest of the family to join us.

Years later, when my mother decided that a serious dose of culture would be good for my development, I spent a year in West Germany—attending school, visiting my father’s family, and discovering architecture, art, and history. But Germany was still sharply divided, the East an impenetrable no-man’s-land, and I never got anywhere near the place of my birth.

After the Wall’s collapse, my eldest brother went to visit the home in East Germany he’d lost at sixteen. One of its several squatter-tenants gave him a ring he had found there, inscribed with our father’s initials and a 1928 wedding date. Convinced that it would soon be time to reclaim the estate, my brother argued that the family should all chip in for a new roof. What had truly been home to him I knew mostly from photo albums, starring people and places I was too young to remember. Time, daily life, and bureaucracy intervened; the roof project lapsed.

The notion of home is a perpetual prickle that plagues all refugees and exiles, apparently even me. Maybe it’s just modern geopolitics, maybe it runs in families. It certainly ran in mine: My father was exiled at fourteen by Bolsheviks and my brother at sixteen by the Soviets. My mother, living in Germany in 1929, wrote to a friend in the United States that she “felt in a thousand ways an exile.” As a child in postwar America, and the only “Nazi” on the block, I occasionally felt an ill-defined prickle, too.

In the spring of 2019, while Germany prepared to celebrate three decades since its reunification, I received an invitation to a memorial service for my godfather, Alexis von Roenne, from his daughter Adelheid (Heidi). The service was scheduled for October 12, seventy-five years after Roenne was executed on Hitler’s orders. It was to be in Malchow—about 135 kilometers northwest of Berlin, deep in the Mecklenburg Lake District, near where my parents settled in 1932 and where I was born. The invitation roused whatever notions of home had loitered in my consciousness over the years.

Maybe it was time to honor the godfather I never knew. Maybe it was time to put my mythical notions of home to rest. So what route should the trip take? The only certainty was the memorial service; after that it could be whatever I made it—a history lesson, a sentimental journey, or an ad hoc adventure, going wherever curiosity took me.

The euphoria encapsulated by that T-shirt at the Frankfurt Book Fair had evaporated, but I wanted to see whether there actually was one fewer Germany. After World War II, West Germany went through a period of self-examination. A new, inimitably polysyllabic German word, Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past), entered the dictionary. After reunification, the other half—the Ossis—struggled to overcome years of bleak, dispiriting sovietization, not to mention the Nazi period. There was not just one German past to overcome, but several. I wanted to find out what overcoming so much history meant.

Landing in Berlin, I was self-conscious about my elementary German. It had been refreshed occasionally over the years—with family and colleagues, during professional visits to Frankfurt—but I had used it very little recently, and it was rusty. Many Germans speak far better English.

I avoided Plötzensee Prison. Visiting the stark chamber fitted with meat hooks where Hitler had plotters and opponents gruesomely strangled was not why I was there. I had come to pay respects, to honor my godfather’s memory, not to dwell on death.

But visiting No. 16 Burggrafenstrasse was different. My parents had lived there in the Thirties before their move to Mecklenburg. It had been lovely. The house had a garden out back and was near the Tiergarten, in a district teeming with other émigrés. A visiting American friend had filmed my young father descending the broad steps, jauntily adjusting his hat. But I found no wide, easy steps, no house, only a long row of innocuous new apartments. I should have known better. The area had been heavily bombed.

This was not true of where I was headed. Mecklenburg is rural and emphatically agrarian—not exactly frozen in time, but occupying a very different space. Repeatedly partitioned between ruling duchies, much of what is now the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern was under totalitarian rule for centuries. In the nineteenth century it was seen as a backwater, resistant to industry, railroads, or innovation of any kind.

Then came Bismarck. Applying realpolitik, the Iron Chancellor cobbled together a group of loosely connected states to form the basis of modern Germany. Local self-interest persisted, of course, but a bit of blood and iron, and some military victories, reinforced the fragile thread of common language.

Bismarck is said to have remarked that when the end of the world came, he hoped to be in Mecklenburg because everything happened there a hundred years later. After forty-five years of Communist rule, Mecklenburg’s distance from Berlin is more easily measured in light-years than kilometers—no small part of its charm. Malchow’s tidy houses lie cheek by jowl on the cobbled streets. No Germlish spoken here. Mercifully, by the time I arrived, the rust was beginning to flake off my German, my tongue reacquainting itself with the language’s particular patterns.

The town gives no hint of its freighted past—of Wendish tribes, of twelfth-century Saxon raids, or the munitions factory Dynamit Nobel built there in 1938, later staffed with forced labor from a neighboring concentration camp. Today, sailors, bird-watchers, and leisure seekers of all sorts enjoy the placid pleasures on offer.

If ever I hope for eternal rest, Malchow’s cloister cemetery is where I might find it. I arrived early, and was greeted by the genial Dieter Halbig, whose many interests include supporting and maintaining the cemetery. He suggested coffee at the cloister café, housed in the former Cistercian nunnery across the way, but I wanted to take in the deep peace of the place. Cypress trees and an immense weeping beech punctuated the early October mist. The service was to be held in a small chapel with an overflow tent nearby.

Napoleon’s armies passed through Malchow en route to Russia, and the cemetery holds soldiers who died despite the efforts of the cloister’s nurses. There are also the sisters themselves, local gentry. Roenne’s wife’s family had deep roots in the region, and she is buried there, too. His name appears on her tombstone, but only his name. Victims of Hitler’s cruelty were not granted burial; the whereabouts of their remains are unknown. (My father was buried in July 1941, in a very young apple orchard on the banks of the Dnieper. His commanding officer sent us a photograph of the grave. That simple cross in Lupolovo is surely gone, the nascent orchard either matured or disappeared beneath modern expansion.)

Roenne and my father had probably met in the Potsdam Ninth Infantry Regiment, if not before that. They shared a Baltic background, with all the loss and displacement that entailed. They also shared a strong faith, a love of France, and a deep distaste for Communism. In 1940, Roenne, then a staff officer, had pulled my reservist father into intelligence work for Foreign Armies West (FHW) in France, where his education and language skills would be useful. Like Roenne, my father feared Soviet hegemony and longed to restore a lost Baltic home. Roenne later enabled my father’s participation in the Nazi invasion of Russia.

Jokingly referred to as Graf Neun (“Count Nine”) or von Neun because of its heavy aristocratic contingent, the regiment eventually became a hotbed of resistance, numbering more victims of Hitler’s wrath than any other German military unit. Roenne loathed Hitler and all he represented. Though not at the epicenter of the July 1944 assassination plot, Roenne knew of it and said nothing. He was arrested, released for lack of evidence, then arrested again and executed.

Small notes smuggled to his wife through a prison warden speak to Roenne’s motives. He abhorred Hitler, but he also foresaw an unwinnable war, a Russian invasion, and the dismemberment of Germany. He spells out his devout Christianity: perhaps God did not want to forgive Germany her terrible sins. Another note suggests, rather optimistically, that in some distant future the world might recognize that the German General Staff resisted by throwing itself “under the wheels.”

With Soviets pressing from the east and the Allies landing in Normandy, Roenne had gone to inspect the front lines when his civilian car suddenly encountered an American convoy. A trusted colleague from his FHW days in France who was traveling with him later stated that surrender would have been a simple matter. But Roenne, unwilling to turn his colleague and their driver into American POWs or subject his wife and children to Sippenhaft, the Nazi system of collective guilt, returned to duty at the Zossen headquarters.

I peered at the gravestone bearing only Roenne’s name. I had read much of what was available about him: a slim entry on Wikipedia, a family tree on Google.de, Ladislas Farago, David Kahn, some questionable websites, David Alan Johnson’s Righteous Deception, and Ben Macintyre’s Operation Mincemeat. I had also read Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker article on the complexities of espionage, which examines whether Roenne’s anti-Hitler sentiments affected his actions as chief of FHW.

The British had concocted Operation Mincemeat to delude Hitler about the site of planned 1943 Allied landings in southern Europe. In a maneuver fraught with innumerable what-ifs, the body of a phony British Royal Marine was floated off the Spanish coast to draw attention away from Sicily as the locus of invasion.

Intelligence operates within a haze of duplicity, with two (or more) often equally confused sides to any equation. Here, the opacity presents a conundrum: Did Roenne knowingly pass on false information?

“Mincemeat swallowed hook, line, and sinker,” crowed the British intelligence. Others believed, as Johnson did, that Roenne knew better, and deliberately deceived Hitler, not only about Mincemeat but also about the number of Allied divisions and the site of Operation Overlord. Macintyre suggests that Roenne was not fooled by the elaborate deception, as the British hoped he would be. But Magnus Pahl, of Dresden’s Bundeswehr Military History Museum, regards such claims, especially in English literature, as exaggerated. And Roenne’s daughter believes deliberate deception to be inimical to her father’s moral code.

Suddenly, I spotted Heidi’s son Christian, handsome and so tall it was hard to imagine that he had sprouted from his petite mother. I’d known him when he was interning at a publishing house in New York before starting a legal career in Hamburg. Walking and talking, we slipped into the small Organ Museum, catching up.

The ceremony brought together generations of Roenne’s family, along with lawyers, historians, pastors, government officials (mostly gray or graying), godchildren of Roenne’s (like me), and those of his friends and colleagues. I knew few of them, but we were all connected, if not directly to that fateful 1944 plot, then by a web of like-mindedness.

Godparenting is serious business here. I had met Roenne once, as a three-month-old. Wounded on the first day of the Russian campaign, he had come to meet me and to offer condolences on the death of my father, whom he’d last seen being evacuated from a field hospital. Though my father had been clear-eyed about what lay ahead, Roenne felt responsible. But since then, he said, he had seen terrible things; my father may have been spared the worst.

At the service, Pahl gave a speech that outlined Roenne’s story. Ministers and government officials paid their respects, songs were sung, a wreath was laid. Some attendees had trains to catch or long drives home. Everyone else gathered at the café to reminisce, greet old friends, meet new ones. “Ahh! You came from New York!”—and conversations began, about the past, the present, even some silly speculation about the future.

Seated to my left at dinner was a godson of Hasso von Boehmer, a senior staff officer who was executed for anti-Hitler activities. Had my father survived, I wondered, how might he have fared?

When I told my dinner companion about trying to visit the home I did not remember, he said he had gone to visit the town where he was born—a town now half-Polish, half-German, its two names witness to historical chafing. Standing pensively in front of his family’s former house, he was approached by a stern official who asked what he was doing there. He had come to see the house where he was born, he explained; he had always been curious. The official’s harsh demeanor melted. He had been born there, too, he said, when it was on the other side of the divide. They talked about families, fate, the treachery of maps, and the abundant peculiarities of modern life.

Halbig had planned an evening outing to watch the cranes, a celebration of the birds’ annual migration. On the way out of town, a monument with a Cyrillic inscription and a star, hammer, and sickle caught my eye. Halbig said it honored the Russian soldiers who had died there in 1945, a few among the estimated millions.

I was fascinated. I told him about the debate over Confederate monuments that had erupted in the United States after Charlottesville, Virginia, proposed removing a statue of Robert E. Lee. Other cities had removed monuments to Confederate history, which was alternately viewed as a necessary correction and as a whitewashing of the past.

When I asked how locals felt about the Russian memorial, Halbig was quiet for a minute. “Well,” he said simply, “it’s history.” His answer raised the question: What is history for anyway? How do we deal with it? Ignore it, rewrite it, erase it, or use it as a tool? Later, I learned about the 1990 agreement between the German Federal Republic and the Russian Federation guaranteeing the protection and maintenance of Russian graves. In the moment, though, Halbig’s answer felt right, a metaphorical talisman to carry with me.

Clustered in a viewing blind, a guide was quietly instructing a small group about this celebrated phenomenon: cranes from the Baltic states and Scandinavia, even Russia, migrate south on a long pilgrimage to Spain, the south of France, and North Africa.

We were intent on keeping quiet; the birds are easily spooked. Nattering and squawking in the twilight, they were feeding in the large marsh before spending the night on a nearby lake, safe from predators. Pale apricot and mauve clouds streaked the western sky. Suddenly a scattering of silhouettes flew across the horizon, long necks stretched forward, immense wings caressing the air. More nattering from the marsh; the question seemed to be whether to grab a last bite or go now, before total darkness.

As we made our way back to town, an immense orange moon hung round and full above us. Another seasonal phenomenon—the gorgeous orb of the hunter’s moon—seemed a fitting close to the day. Never mind that it got its name because it was thought to illuminate hunters’ prey.

There was no traffic headed east from Malchow—in fact no traffic at all. Roads ran nearly straight, turning off to other villages at tidy right angles, trees planted on either side as a windbreak. Sun and silence gave a wonderfully sleepy quality to the broad, undulating fields. Most were newly plowed and harrowed or already sprouting tender shoots of winter wheat—a shimmering green buzz cut.

Mecklenburg’s idyllic qualities belie a long and turbulent history. Tumuli are so old they’re simply curiosities, bearing little emotional load. But the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) is different. Mention it in the United States and the usual response is a quizzical shrug. In Mecklenburg it left lasting scars.

Describing that war means raiding the lexicon of misery. Plunder, plague, and pestilence come quickly to mind, starvation and death not far behind. The wretched litany is a nearly Hobbesian nightmare: nasty and brutish, but not short. I remembered how it began—the absurd defenestration of Prague—but I had to grope dimly through my history lessons for more. A conflagration that began as a religious conflict, the Thirty Years’ War ultimately devoured 20 percent of Central Europe’s population. In Mecklenburg, once wartime casualties, famine, and plague are accounted for, the toll may have been well over 50 percent.

Albrecht von Wallenstein, a Bohemian mercenary, played a big role in the catastrophe. Nominally, his allegiance was to the Holy Roman Empire, but in fact he fought only for himself. Profiteering, rapaciously marauding, pillaging, killing, he fed his armies whatever was at hand, leaving starvation behind. Poor, afflicted Mecklenburg, only one of his rewards, was hardly enough; many other territories became booty.

More wars took their toll, then Soviet rule left the population poorer still. Fixed prices made agriculture, the region’s main industry, unprofitable, leading to food shortages yet again, until the lack of nearly everything spurred a desperate exodus westward, where hope beckoned. The East German population shrank by 25 percent.

The Wall’s collapse led to mass defection. Enterprising youth went west to find a better life, leaving behind a disenchanted older generation to contend with the grim consequences of Soviet occupation. The Communists were gone, but a sour, aggrieved resentment lingered, shaping a right-wing turn. In March 2020, Germany’s domestic intelligence agency labeled Der Flügel, an extremist wing of the Alternative for Germany party (AfD), a threat to German democracy, and put some of its leaders under surveillance. Though national AfD leadership recently voted to dissolve Der Flügel, local leaders remain active.

The Mecklenburg-founded Nordkreuz is an extremist group that is stockpiling weapons and ammunition in preparation for Day X, a magical, mythical moment when the present social order will allegedly collapse, making way for a new Germany, free of immigrants, peopled only by Schmidts, Schneiders, and Müllers. This may sound like a fantasy, but earlier official skepticism is being replaced with alarm at the group’s metastasizing presence in military and police circles.

Ultimately, in spite of the euphoric promise of reunification, in spite of increased federal funding, there are still two Germanys: one a potent, recognized world power, the other backward, haunted by years of Stasi terror (one informer for every 6.5 citizens, by some estimates), and suffering from an abiding sense of neglect, considering themselves victims of history. There’s a past to overcome.

Comfortably settled in the placid landscape is a beautiful old brick-and-timber manor house typical of the region. The house, now a museum, was briefly home to Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of Troy. Across an expanse of grass, a wooden replica of the Trojan Horse offers visiting children a slide down its long tail. Schliemann’s father, the pastor of the church across the way, had filled the boy’s head with Homer’s classics, encouraging his interests however he could. Poverty crimped the boy’s education but not his spirits, and by thirty-six, he had demonstrated sufficient entrepreneurial talent to attain independence. A jack-of-all-trades, an extraordinary linguist, and an energetic world traveler (if a bit loose with facts), he devoted himself from then on to his true passion: archaeology. Criticism and controversy about his methods (a bit of dynamite) and interpretations swirl, but the gold he found remains. Smuggled out of Turkey, much of the real treasure went to a Berlin museum until 1945, when it went to Russia (booty once again).

Had the museum been open, I could have seen replicas of the glittering treasure, such as the so-called mask of Agamemnon from Mycenae. The story goes that Schliemann countered arguments that this mask was not in fact that of Agamemnon by saying, “All right, let’s call him Schulze.”

The 750-year-old church across the road is an amalgam of stone, brick, and timber. Its Romanesque interior is adorned with primitive frescoes of garden-variety Christian iconography: St. George slaying an anemic dragon, two Marys at the cross, the raising of Lazarus. One surprisingly vivid devilish entity, noticeably larger and more energetic than the saints, is a reminder of the Slavic Wends, who ruled the region from the fifth to the twelfth century. Just beneath him, in a miraculously evenhanded nod to history, is a cross.

Halbig’s lesson has been neglected in much of the former East Germany. Statues paid for with voluntary donations have been retired, streets and squares renamed. Karl-Marx-Stadt went back to being plain old Chemnitz. At some point after what Germans call die Wende (the turning), producing appropriate signage in response to changing times must have been good business.

The malleability of history finds an analogy in a painting by the nineteenth-century Romantic Caspar David Friedrich: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. Typical for Friedrich, who was born in the region, this lonely wanderer is center stage yet oddly dwarfed by the suggested immensity of his surroundings. His children and grandchildren may survey this same landscape in a very different light. The crags he sees may have disappeared, as others, previously hidden in mist, take on new importance.

There is not one history, but many: First it is told by the victors, then rewritten ad nauseam, “facts” rearranged, reinterpreted, adapted to suit the times, particular inclinations, political expediency. Nothing seems constant. That’s been true since Thucydides. Though East Germany has tried to expunge its Soviet past, much of it is still peopled by tangible ghosts. Tracking the fate of statues can be time-consuming, yet doing away with them poses other problems.

On a dark November night in 1961, in the era when Khrushchev was formally denouncing the cult of personality around Stalin, workers dismembered the sixteen-foot statue of the Red God that stood on Berlin’s Stalinallee. But what was to be done with the icon’s weighty remains? Some pieces were said to have been melted down to become bronze bunnies for the zoo. Stalin’s large ear, surreptitiously rescued by workers, found its way to Café Sibylle, a popular gathering spot. Ironically, financial troubles eventually led the café to sell plastic replicas of Stalin’s ear to tourists.

Lenin proved a more durable hero. For twenty-five years, his four-ton, goateed granite head lay buried to shield it from anti-Communist vandalism. When it was unearthed for an exhibition of forgotten monuments, one unnamed Berliner quipped: “Lenin to rise again? That doesn’t work. History is over.”

Hardly. Malleable, perhaps, but history is far from over. In Schwerin, twenty-five years after the Wall came down, a bronze statue that was thought to be the last Lenin standing proved to be as immune to protesters throwing a hood over his head as to a sidewalk message in red paint asserting lenin stays. The mayor argued that Lenin’s continued presence raised important questions and encouraged debate. Getting rid of a monument reflecting so significant a period in her city’s history “wouldn’t change the way people think.”

Tending soldiers’ graves, however—a condition of Soviet departure from East Germany—continued. Streets and squares may have been renamed, but even out-of-the-way graves are maintained. Students, retirees, and other volunteers participate. In a bosky corner of Blumenholz, the property that adjoins my family’s Blumenhagen, lie six war graves from 1945: Germans, Russians, and one unknown. Not surprisingly, their death dates coincide neatly with my family’s departure.

A modest square stone set into the ground marks the grave of Konstantin Balakin—May 21, 1921, to June 18, 1942. That simple marker, cleared of grass and weeds, may not be what the stipulation for Soviet grave maintenance intended, but it delivers a message more potent than all the bombast of Berlin’s immense Treptower Park monument. Plain, unpretentious, deeply affecting, the stone marker is a reminder that history is inescapably personal. There is nothing public or universal about it.

A woman, stooped, slight, gray, was determinedly sweeping up the yellow leaves brightening the pavement in front of her small house across from the medieval octagonal church in Ludorf. Asked how she felt about the anniversary of the Wall coming down, she stopped. The leaves fell before the Wall, she sighed. The leaves fell during the time of the Wall, and the leaves fall now, as they have always fallen. “Now, though,” she said, sighing again, “the leaves fall in spring, in summer, and in the fall.” She went back to her task. Maybe she was referring to global warming, or maybe autumnal nostalgia had trapped her in a past that was no longer reachable.

Reverence for nature in all its forms is common in both Germanys, but the forest, more than providing a reliable backdrop for folk and fairy tales, holds a special, nearly mystical place in the German heart. The Roman historian Tacitus’ treatise on Germania credited the dense, mysterious forests of the ancient Teutons with keeping Roman legions at bay. Maybe Tacitus started something, maybe it predated him, but some of his views seemed made-to-order for the Nazis. In the south of Germany, remnants of Roman sentries’ huts along the frontier are now hidden by woods. Well into World War II, desperate shortages meant that anything labeled 100 percent wool was suspected of being 100 percent Deutscher Wald.

The woods on the way to Ravensbrück bear no relation to the deep, scary forests of German fairy tales. Planted for lumber, they stand narrow and tall in straight rows, the brush cleared away. Given that I was headed toward an infamous concentration camp, it was easy to equate these woods with methodical regimentation and exclusionary thinking. More likely, they simply reflected an organizational mindset meant to counteract critical losses.

In February 2020, the American carmaker Tesla was cleared to level 227 acres of forest to build a factory near Berlin. An outcry from environmental groups led the company to promise to relocate ants, bats, and reptiles, and to build four hundred nesting boxes for birds being ousted from their habitat. Where Little Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel will resettle is unclear.

Glorious October sun drenched the deserted Ravensbrück during my visit. From 1939 until the arrival of the Soviets in April 1945, it was used as a concentration camp for about 130,000 women, nearly half of whom died there. As the Soviets approached, ethnic Germans were released, and the SS leadership mustered the prisoners still able to walk for a death march north. My mother recalled encountering such marches as our family fled the Russian advance. After the evacuation, Red Cross personnel took charge of the approximately two thousand desperately sick prisoners left behind.

The place was so still, so sunny, so vast, it was impossible to react to those bald facts. The barracks are gone. On an immense platform by the lake, a statue of an attenuated woman holding an equally attenuated child tries to memorialize the inhumanity of the place, but I missed the humble directness of Konstantin Balakin’s memorial stone. Only conversation with the other visitors gave the site meaning.

Standing near the small crematorium, I met another woman’s teary eyes. Haltingly, she told me that her Polish mother had been imprisoned here. A young girl at the time, she was considered strong enough to haul carts of the dead day after day—a horrifying, physically exhausting job. Eventually rescued by the Swedish Red Cross, she had grown up in Sweden. Now her daughter and I were on much the same mission—unearthing the past. Her husband told me that when the liberating Soviets arrived, they gathered any remaining camp personnel, put them in Soviet uniforms, and sent them off to the front lines. The truth or fiction of this story depends on which era shaped it.

The town nearest the spot my parents decided to make home in 1932 is Neustrelitz, population 21,000. The old town slopes toward Lake Zierker. The hospital where I was born is now a high-end condominium complex. The marketplace holds banks, the town hall, a boutique, a pizza parlor. At an expansive café and ice cream shop, locals enjoy pastries and visiting with friends.

As I sat at the café, my mother’s experiences all seemed very long ago. Nearby, children were running in circles around a memorial to Russian soldiers who died there in 1945. I was in a crow’s nest, observing a historical palimpsest.

At breakfast that morning, hearing that I was a native, the chatty waitress had given me that day’s local Strelitzer Zeitung, saying one article in it might interest me. In the placid late-afternoon sun, I read about that dark time. In a secret cubby of an antique desk bought at an estate sale, the Texan Tim Mallad discovered a long letter written by a refugee from East Prussia who had been taken in by a Neustrelitz family: Willy; his wife, Dora; and their thirteen-year-old daughter, Ulla. The letter recounted the terrible events of April 29, 1945: Russian soldiers banging on their door, then repeatedly raping Ulla and her mother. Anticipating further horrors, the family had made a suicide pact and acted on it, something not uncommon at the time. Mallad said his efforts to locate the Weisses’ survivors made them feel like his family now. What became of the letter writer is unknown.

I kept getting closer and closer to Blumenhagen, a place that had been immortalized in home movies and albums. I had googled it, of course, and seen the lake just below the house where my siblings played, swam, and sailed, seen the dachas that East German officials had built along the shore. More recent Google viewings were harder to decipher; piecing together photos of a place of which I had no real memory didn’t help. Now I was nearly there, that mythic home acting as a magnet. Still I was deeply reluctant, clearly dragging my feet. My mother never went back; maybe the past should be left undisturbed. But like a determined homing pigeon, I could not seem to stay away.

When my parents considered buying the place in 1932, the roof was in disrepair, but it was hardly the property’s only problem. “Ça ne vaut pas la peine,” my father’s cousin sniffed on his tour. And it had, my mother later conceded, “gone to rack and ruin.” But my unemployed father and well-heeled mother were young and energetic. They had big dreams. It would be an escape from the political chaos of Berlin, yet within striking distance of the capital—when and if he found work. At more than seven hundred acres, it might have served as a stand-in for the idyllic, largely self-sufficient home his family had lost to the Bolsheviks in 1918. For their growing brood, it would be Eden.

Purchased and renovated with American dollars, it had new French doors at the back that opened onto terraces laid out above the lake. They built a greenhouse, gardens, and an apple orchard; each of my older siblings was charged with planting a tree. My parents’ rosy dreams had started to become reality. Then war broke out. My father was killed. I was born. On April 27, 1945, my mother loaded everything that mattered most onto a horse-drawn farm wagon just ahead of an advancing Soviet army, hoping to find—God willing—American lines.

My older sister told me recently of a wonderful dream she’d had of being nine or ten years old at Blumenhagen, her body and spirit awash in childhood magic—all peace and glory. She should hang on to that talisman. The reality I encountered was hemmed in, no lake or gardens visible, no walnut tree by the kitchen door. Sideswiped by history, I should have abandoned the search long ago. My mother knew better, planting a tree and making wherever she was home.