“Woman and Lilies,” by Jo Ann Callis © The artist. Courtesy ROSEGALLERY, Santa Monica, California

In literature and film, something happens when women hit forty, or nowadays perhaps forty-five: the earth opens up and swallows them, until they’re spat out again decades later as grandmothers or wise old aunts in peripheral roles. The menopausal (or in this case, perimenopausal) protagonist is rare, which is just one thrilling aspect of Dana Spiotta’s new novel, Wayward (Knopf, $27).

Sam Raymond is fifty-three, a wife and mother living in suburban comfort on the outskirts of Syracuse, New York. She has a part-time job at a historical museum called the Clara Loomis House; her daughter, Ally, is a studious high school junior, though Sam “was used to her mother love being unrequited”; her husband, Matt, is “practical and constant”; her own adored mother, Lily, is unwell, but refuses to discuss it. Sam, as we first understand, discards this stable life in a sudden passion for a house—“a run-down, abandoned Arts and Crafts cottage in a neglected, once-vibrant neighborhood in the city of Syracuse”—that she purchases on a whim, leaving her marital home in the process.

But we quickly come to see that the reasons behind this apparent act of madness are, in fact, complex. One catalyst is the 2016 election:

The world had moved against her more than it had moved against Matt. To him it was the equivalent of watching his beloved Mets lose a closely contested World Series. To her it was much more than that; what exactly it was, she did not yet know.

Another is her mother’s mysterious terminal illness. A third is her own hormonally disrupted existence—not only the insomnia and hot flashes, but the novel experience of overwhelming anger. “That was yet another real reason she had to change her life: her fucking rage.” Sam burrows into several women’s groups online and in person (Spiotta is highly amusing in her renderings of these; one of the novel’s many pleasures is its humor about the humorless) and allies herself, ultimately, with two women, Laci and MH, who encourage her (disingenuously, it transpires) to renounce everything in a Dorothy Day–like way and lead an antibourgeois life. Sam, like her creator, is alive to the ironies of her faux poverty: she has the money to buy her dilapidated house in cash; she gets a monthly allowance from her prosperous husband; she can walk away from this new life at any time. But she revels, nonetheless, in the upending of all she has taken for granted and in questioning, radically, her roles as wife, mother, and middle-aged woman in this unraveling world. As she considers her personal trainer, Nico, a further appurtenance of her age and station, she reflects on

the progressing, ever-widening gulf of disparity in every sphere. And were we not also on the verge of an environmental apocalypse? People seemed more fixated than ever on notions of “self-tend, self-care, self.” In the current context, wasn’t naked pursuit of health obscene?

Spiotta’s novel is at once satirical and earnest: Sam asks what she can do to atone for her thoughtless privilege, what role she might play as an agent of change. There’s much comedy in the asking (menopausal feminists delivering deliberately unfunny monologues at open-mic night at the local comedy club prompts an uneasy titter in both the audience and the reader), but the novel makes clear that the answers aren’t straightforward. Almost everyone—including the (fictional) nineteenth-century feminist Clara Loomis, in whose museum Sam works—proves to have feet of clay. Loomis was an idealist, but also a eugenicist; MH, a radical leader who has supposedly renounced materialism, wears expensive jeans and motorcycle boots and owns a lake house. When Sam witnesses a crime in her new neighborhood, she realizes swiftly that her capacity to help is limited. She can’t determine Ally’s future; she cannot save her mother.

Spiotta’s novels are unfailingly dense with life—the textures, digressions, and details thereof—and Wayward is no exception: she braids diverse strands, including a number of sections from Ally’s perspective, so that by the end we have lived with Sam in her various roles, in the past and the present, in her intimate psyche and her broader cultural plight. Spiotta offers grand themes and beautiful peripheral incidents: for example, she describes an unforgettable and tender scene in the locker room of the local Y, where Sam sees a mother and her adult daughter, who has Down syndrome, bathing together and reflects on bodies, fear, shame, and joy. She writes with sly humor and utter seriousness.

For this reader, roughly the same age as Sam Raymond, there is uncommon pleasure in the paradoxes of this climacteric tale. Whether it’s a matter of the era or of my age, the following offers a rare articulation of midlife now:

She didn’t want what lay ahead, the future, for the first time in her life. She wanted that moment [of a decade before, when her daughter was six and her mother was well], and all the ordinary moments before and after it. . . . All of it felt better than now.

Pedro Mairal’s The Woman from Uruguay (Bloomsbury, $24), deftly translated by Jennifer Croft, explores a similarly transformative period in the midlife of its protagonist, Lucas Pereyra—except that in this case, the author’s subject is a stripling of forty-four, and the events unfold in the course of a single day. Mairal, an acclaimed Argentine novelist, offers a slim and eminently readable iteration of the genre, delivered in the disarming voice of a feckless novelist turned house husband. Lucas is self-deprecating (“I wasn’t the only one there who was elderly and eclipsed”) and witty (his son, in infancy a “tiny little elderly man, that haiku of a person,” is now like “a drunken dwarf who gets really emotional”). He is also uncomfortably honest. (“I’m almost certain that there is nothing in the world a man likes more than being told that [his cock is beautiful]. It’s better than being told he’s a genius, or that you love him, or whatever.”) He tells his story to his wife, Catalina, the mother of their young son, Maiko, as a form of confession and justification. Having suspected her of infidelity (“Doubts grew like vines, surrounding me”), he has used this as an excuse for his own dalliance with a much younger woman in nearby Montevideo—she of the novel’s title, Magalí Guerra Zabala, known to Lucas as Guerra (“war”). The two met at a literary festival, kept in flirtatious touch, and have seen each other a couple of times. The occasion of the novel is a further reunion, for which Lucas has high hopes.

“Lady of Shalott,” by Cig Harvey, from her monograph Blue Violet, which was published in May by Monacelli © The artist. Courtesy Robert Mann Gallery, New York City

The premise of the fateful day has him traveling by ferry and bus from Buenos Aires to Montevideo to retrieve $15,000 in cash that he will smuggle back across the border under his clothes. The money, advances from his Spanish and Colombian publishers for two books he is contracted to write, will enable him to settle his debts and to work unimpeded for “nine months or maybe even ten.” Were the money to be sent directly to Argentina, it would be subject to a punitive exchange rate; hence the ruse. But as thrilled as he is by the minor derring-do, Lucas is exhilarated by the fantasy—even as he recognizes it as such—that Guerra, and Uruguay, will solve all his problems. “That was Montevideo to me. I was in love with a woman and in love with the city where she lived,” he muses. “And I made up everything about it, or almost everything. An imaginary city in an adjacent country.”

Lucas, a flaneur for several hours, reflects on, among other things, the ubiquity of screens (“At some point, without realizing it, all human beings became Rain Man”), his privileged upbringing, a poem by Borges, the beauty of pregnant women. Shortly after Lucas, waiting for a tardy Guerra, has realized that if they fail to meet he will be “freed . . . from trickery and lies,” she arrives with her ex-boyfriend’s pit bull in tow, “a jaw of a dog, rough, tough, a canine cudgel of lethal chomps, a Tasmanian devil with a huge square head.” Lucas, who has paid in cash for a room at the Radisson, thinks at once, “We can’t go to a hotel with a dog.”

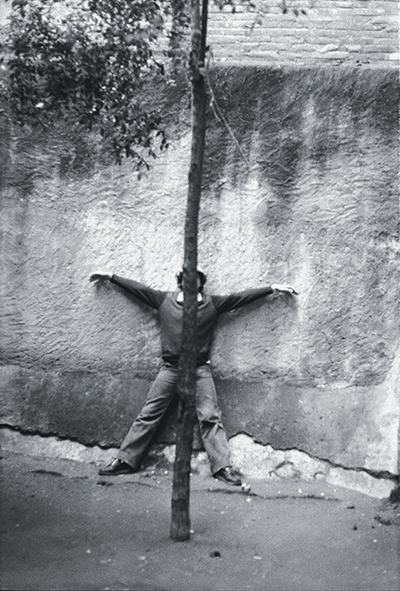

“Autorretrato fusilado (Executed Self-Portrait),” by Marcelo Brodsky, 1979 © The artist. Courtesy Henrique Faria, New York City

From this moment on, having ascended to the peak of fantasy, Lucas will repeatedly, in ways he never imagined, be assailed by reality—starting with Guerra: “Who is this person? She was like a total stranger. It was hard to match her to my months-long delirium.” Guerra then breaks into tears as she tells him about her recent breakup, her discovery that her boyfriend, César, and her roommate, Rocío, have been sleeping together. “I’m terrified of women crying,” Lucas thinks. “How did I get mixed up in this Venezuelan soap opera?” The two get drunk and stoned together, then embark on a series of misadventures that will unravel not only the day’s plans but Lucas’s life as he has known it.

The novel is suffused with a rueful bemusement that befits its protagonist:

I was in the exact middle of my life, up until then I had been just getting started, but this was the boundary line, the end of the rainbow, as far as the rope could go down, now all that remained was to return, to travel the staircase in the other direction, untwisting myself.

With an insouciance greater than that of Spiotta’s intense Sam, Lucas makes light of his travails, and the novel feels, even at its darkest, almost like a comic romp; but Mairal gives his character the gift of frankness, and in his uncomfortable admissions and meandering reflections, Lucas, too, comes to accept the limits of his agency and the ineluctable force of reality. Midlife once again proves to be about compromise, and the freedom that comes with resignation.

Sunjeev Sahota’s third novel, China Room (Viking, $27), takes place in one locale—Punjab—across two time periods, seventy years apart. It, too, examines individual agency and the lack thereof, albeit from very different angles. The book opens in the summer of 1929, on the day after a triple wedding: the widowed Mai’s three sons, Jeet, Mohan, and Suraj, have married Mehar, Harbans, and Gurleen in a single ceremony to save money. But in this deeply traditional household, the women don’t know who is married to whom. Just as the three brothers share a bedroom, so too do the three women: the china room of the title, so-called because of the crockery on the walls, part of Mai’s dowry. Each is summoned intermittently by their mother-in-law to have sex with their respective husband in total darkness in a third room set aside for the purpose.

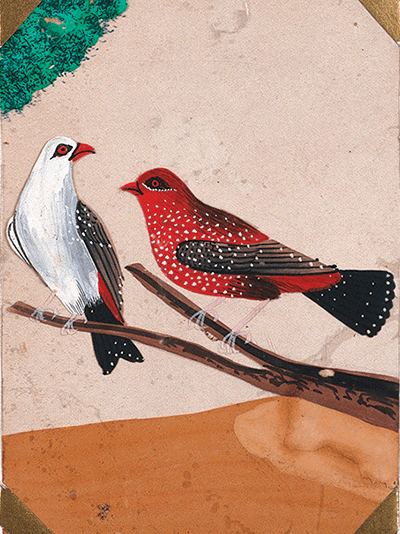

A nineteenth-century Indian painting of two birds on a branch. Courtesy the Wellcome Collection, London

The narrative cleaves to Mehar Kaur, just fifteen, as she finds her footing in this new life, serving at the whim of the flinty and ungenerous Mai. Sahota gives us a glimpse of what she has left behind—a loving family that includes her doting male cousin Monty, raised like a brother, who endeavored to save her from the marriage arranged when she was only five. And Sahota creates an all but unbearable tension as young Mehar, by nature spontaneous and affectionate, attempts to figure out which man is her husband—such a natural wish, yet one that proves perilous—so that she can love him.

Juxtaposed with this spare but evocative historical account (based in part, we are told, on the author’s family history) is a first-person narrative set in 1999, in which a young British-Indian man of eighteen, awaiting his (lamentable) A-level results, spends the summer with his maternal uncle Jai and aunt Kuku in the village of Kala Sanghian. Things get off to a bad start when the unnamed narrator, charged with babysitting his cousin Sona, allows the small boy to become seriously dehydrated while he himself stocks up on liquor for clandestine consumption. The narrator is, in fact, secretly in withdrawal from a heroin addiction that was prompted by the unbearable miseries of his youth as a South Asian boy in Britain’s white, working-class north. His uncle and aunt bring in the local doctor, who misdiagnoses him with dengue, while an overlooked junior medic, a woman named Radhika, rightly assesses the problem. The narrator, ashamed, retreats to the family’s abandoned compound, where food is delivered to him daily. Seventy years earlier, that compound, we learn, was the home of Mehar Kaur; and the long-barricaded room in which the narrator chooses to sleep is none other than the china room.

Sahota, whose most recent novel, The Year of the Runaways, was a 2015 Booker Prize finalist, is a restrained stylist whose details bloom in the imagination. Mai’s three sons are described as having “unconvincing shoulders and grave eyes.” The youngest brother, Suraj, makes a trip into town, walking along

a rugged avenue of leafless trees. Ahead, a soda-seller pushes his grubby three-wheeler, his vest stained with an arrow of sweat. He turns down an alley and spots a pink-bellied dog collapsed in the shade, resigned to the flies that hover above like a small raincloud.

In another urban moment, men heading to the mosque in their cotton caps are seen from above: “The white caps are like silken buoys on a surging river.” In a world—or rather, separated by time, two worlds; or indeed, counting the narrator’s British life, three—more forbidding and austere than those depicted in Spiotta’s and Mairal’s novels, there is nonetheless respite, even solace, to be found in precise and exhilarating observation. Sahota’s first-person narrator, kissed on the cheek by a friend,

felt a sharp longing for her, and beside that longing, faith that life need not remain a wail of anger, that it can also be full of beautiful moments that just seem to arrive with the birds.