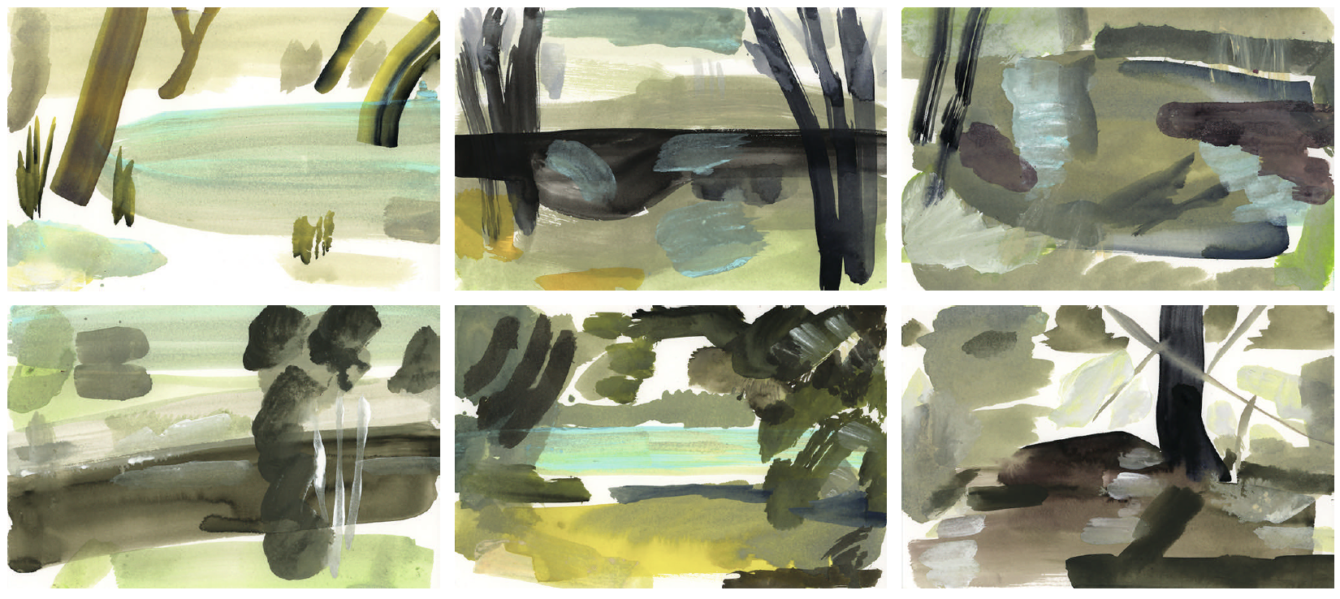

Yuba River, by Billy Childish. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York City

Discussed in this essay:

Waterlog: A Swimmer’s Journey Through Britain, by Roger Deakin. Tin House. 370 pages. $27.95.

In my early twenties, whenever I heard the word “hippie,” I pictured the Haight-Ashbury version: Woodstock, Manson, tie-dye. Then I realized there was another kind of hippie: the British hippie. There was a little music shop on College Street in Toronto called She Said Boom. I’d walk there from the room I was renting a few blocks away. On this particular day, I was probably looking for Mazzy Star or Future Bible Heroes or anything from 4AD. That’s what I was into. But a random CD cover caught my eye: a shaggy, elfin boy-man wearing a rainbow-striped woven sort of sweater thing, beckoning, in soft focus. He was standing in a wood. Nick Drake. Way to Blue. I’d heard the name; I liked the stripes. I want it, I got it.

Nick Drake led to Syd Barrett, Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci, Sandy Denny. Guitars held vertically, played by things with pointy boots and ears. In my head, I connected these sylvan beings to Stonehenge and Tumnus the faun. From my Canadian perspective, the denizens of Britain, great and small, consisted of the bowler-hatted banker from Mary Poppins, Lady Di and the royal family, Merchant Ivory characters, and the Mackenzies and Strachans—the starchy founders of Upper Canada. Mannered men and women, austere. So these wilder and woollier natives blew my mind. I liked them better.

I realized that I had encountered this weight of shag within the bohemian spectrum before: the gentleman hippie. The English eccentric. Withnail and his pal I. Poetry-fed, exuberant thespians and luvvies, accustomed to an audience. A mix of Pan and William Blake: Plake. Shakespeare was totally one. Jonathan Miller, Michael Palin, and Simon Callow, crossed with Byron and the Shelleys. Less psychedelic, more homosexual. Hippies in corduroy. Hippiedom as sensibility rather than pejorative. Lawrence: check. The Bloomsbury Group: check. Hockney: check. Roger Deakin, the writer, activist, educator, and filmmaker: check.

As I reread Deakin’s book Waterlog, I found it shot through with this sensibility. Though it is only now being published in the United States, it was released in the United Kingdom in 1999, and helped launch a national movement of outdoor swimming. It might be the most romantic swimming memoir ever written. Its spirit, and the way it illuminates the joy and complexity of water, of swimming in the wild, places it next to Thoreau’s Walden. As Thoreau “went to the woods,” Deakin went into the water.

Swimming is generally a nonverbal sport. Its soundtrack is burbles and plashes and amplified muffled roars, pops, and tinklings. More than anything, swimmers hear themselves breathe. Deakin details this music. But, as he points out in Waterlog, swimming

certainly appeals to free spirits, which is why the talk is invariably so good in those little spontaneous bankside, beach or poolside parliaments that spring up wherever two or three swimmers are gathered, as though the water’s fluency were contagious.

He gives us this song too.

Deakin died from a brain tumor in 2006. “My house was once an acorn,” he wrote in his posthumously published Notes from Walnut Tree Farm. The farm was his home base, where in 1970 he bought and began to restore a sixteenth-century Tudor ruin surrounded by fields, ancient paths, and crucially, a moat—a beloved, swimmable moat. One rainy afternoon, Deakin, pensive, strokes through his moat and thinks of Neddy Merrill’s long swim in John Cheever’s story “The Swimmer.” Merrill decides to swim home after a pool party by using a suburban patchwork of backyard pools. “He seemed to see, with a cartographer’s eye, that string of swimming pools, that quasi-subterranean stream that curved across the country.” The swims take him through the seasons and, finally, to a Scrooge-like apprehension of his shallow life.

Deakin, nest empty of his son, and at the loose end of a relationship, decides to swim north, through Britain’s rivers and waterways, starting in the southwestern Scilly Isles and ending on the Suffolk Coast. He wants to “break out of the frustration of a lifetime doing lengths, of endlessly turning back on myself like a tiger pacing its cage.” Waterlog gives us a diary of his year of swims, in four hundred pages. Instead of the gin, the drunk neighbors, and the soggy Japanese lanterns that Merrill encounters, Deakin encounters wild bathers, finger-wagging coast guards, tufa, and thyme. Cheever’s reader recognizes the concrete bottom of an empty pool. Deakin beckons his into the depths of the natural world.

indelible swim i

The Sulu Sea, the Philippines, with my brother. I am ten, he’s twelve. We swim for hours before sunset, a couple of our uncles on the beach watching us, sipping bottles of San Miguel. We’ve never felt salt water this warm. None of our cousins get in with us. They turn to their homework, their red-and-blue Game & Watches. One of them has a little Sony Watchman. Pictures from this trip show two tiny dots, our heads, backlit on the swelling orange horizon.

In the Nineties, when he began his cross-country swim, Deakin was an established broadcaster, journalist, and teacher. His vast archive at the University of East Anglia lists the environmental organizations he either founded, chaired, or supported: Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, Common Ground, Houghton Fishing Club, and various wildlife-preservation trusts. In columns, events, and articles he spoke for bees, otters, bluebells, apples, and French cabbages. He practiced and preached bioregionalism.

As Deakin sets off, his reader begins to understand how he sees the natural world. Tiny shells are the souls of drowned sailors; every single flower is named. He follows the flight of a bee or dragonfly so that we share its quotidian errands. He considers the eels he swims with. Really considers them. Paddling happily in a cold river, Deakin describes a split second of a moorhen’s liftoff, giving us its “gangling undercarriage of olive-green legs and spidery feet.” As he stops on a bankside, we see this tiny moment explode into dandelion clocks and “the yellow smudge of lady’s bedstraw. A cabbage-white butterfly explored, alighting on a lost white sock.” He describes a swimsuit left to dry on a hedge and the clicking of the tin changing shed as it expands in the sunshine. Like the hot tin, time expands as he writes it.

I love pleasures that slow down our tempo: kissing, sleep, ice in a drink. Photography is supposed to freeze time, but I find that in its facade of reality, it actually accelerates it. Though Deakin was a filmmaker and avid photographer, he refrains from describing pictures. Instead he averts our glance, makes us look, slowly, at real time: “the water was grained with silt, like an old photograph.”

Leanne Shapton’s studies of Roger Deakin’s moat, for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

indelible swim ii

Woods Hole, Massachusetts. The green August water shifting warm and cold as we bounce deeper. A dog swims out to meet us, delighting my daughter until it licks her. Two women do a heads-up breaststroke, chatting, wearing sunglasses. We wade onto a sandbar and draw lines with our toes in the dark sand.

By nature, I’m a pool swimmer. I learned to swim in pools, trained in pools, competed in pools, am most comfortable in pools. In 2012, I published a book called Swimming Studies about how those perfectly symmetrical, right-angled tables of water have framed the way I see the world. I read the British edition of Waterlog in 2010, as I was writing that book, and understood Deakin as a wild swimmer by nature. My polar opposite. I thought the world was divided into open-water swimmers and pool swimmers. I marvel at people who have the guts to open their eyes underwater in lakes and dark oceans. I’m afraid of the dark. Low visibility fills me with dread. There is no question of the likelihood, when swimming in open water, that I will be bitten by a shark or nudged by a Loch Ness Monster. No question.

What I don’t like about pool swimming, however, are the people. The body has an unspoken territorial boundary in water. Space is propulsion, safety, agency. Any pool swimmer will tell you that having a lane to yourself is like being given the best seat in a restaurant or riding shotgun or sleeping in the middle of the bed. It’s unselfconsciousness nonpareil. This is true of open-water swimmers, too.

Deakin introduces the idea of indelible swims in his first chapter. They are “like dreams, and have the same profound effect on the mind and spirit.” The first of his indelible swims was in the dawn darkness at the local pool before opening hours. “We had the place to ourselves.” His love of swimming is always a little subversive: he enjoys trespassing and has the activist’s ease of being where he’s told not to be. On reading Waterlog for the second time, I realized that my own indelible swims have predominantly taken place in open water. The childhood swims are indelible for their joy, and as I age the swims become unforgettable for darker reasons. By the time I finished the book this time round, pools were starting to look weird to me. Filtered. Merrillesque.

In 2012, the artist Taryn Simon and the programmer Aaron Swartz created the Image Atlas, a website that indexes the top pictures generated for various keywords, using local search engines in nineteen default countries. Today, if I search for the word “swimming” in the Image Atlas, all the results are of swimmers in pools, except for one, an image from Twitter of bathers in Iran swimming in a sort of canal. Not a single picture of a river, lake, or beach.

I have to admit: there is something weird, something wrong about this.

indelible swim iii

The Atlantic, a last swim in Peconic Bay, New York, 7 am, mid-October. The water is glassy, quiet. I wear stubby orange flippers, more for picking over the rocky beach than for speed. I backstroke westerly, against the current and parallel to the shore. In my periphery, I see the cottages that line the bulkhead: thirty-one small wooden summer dwellings, purpose-built for brick workers at the turn of the nineteenth century. A friend had told me about the place, its unusual, perfect scale. Its lawns, its magic. My daughter watches me from the grass. At Cottage Four, I turn and slowly kick back, looking up at the clearing sky. The water is still summer-warm, like a cup of tea left on a desk for an hour.

I’m waiting for the light to change. I look at the tops of the roadside trees, still stripped from winter. Branches resemble river systems, rivers resemble the body’s nervous and circulatory systems. As my turn signal clicks, I imagine all the lakes and rivers in the country, numb from disuse, coursing with lead, sluggish with waste. Then Deakin’s book arrives on these shores. It pumps swimming, splashing bodies into the system, waking it up with a massive human transfusion. Deakin extends W. H. Auden’s line “a culture is no better than its woods.” He adds that this holds true for its rivers too. Sitting in traffic is the opposite of swimming. The light turns green, the vision dissolves.

The remarkable and sad thing about his book is how urgent its concerns remain. Waterlog was a watershed. Deakin led people to water and started a wild-swimming renaissance in the United Kingdom. In the United States, books such as Swimming to Antarctica, by Lynne Cox; Swim, by Lynn Sherr; Nine Ways to Cross a River, by Akiko Busch; and, most recently, Why We Swim, by Bonnie Tsui, have generated a similar interest in wild water. A rallying cry of nature conservation runs through each one. Though the term “climate change” appears nowhere in Waterlog, it’s what the book continues to table in Deakin’s absence.

There’s one moment in particular that illustrates Deakin’s sympathy for the planet. He startles a pair of foxes at a spring near Malvern:

The dog fox scampered off, but the vixen and I just stood looking at each other for fully two minutes. I wasn’t going to move before she did, even if we were there all morning. Then she turned and dragged herself away, towing her paralyzed hindquarters after her. I stood for a long time by theliving spring, too shocked to move, looking at the rank, parted grass where the dying fox had disappeared, wondering how long she could survive.

In Holland, children learn to swim in their clothes and earn diplomas that allow them to use public pools. I don’t know why this practice isn’t encouraged in North America. Few schools and universities have requisite swimming instruction. There was an urban myth that Harvard’s mandatory swim test—now abandoned—was initiated at the behest of donor Eleanor Elkins Widener, whose son (a Harvard student) and husband went down with the Titanic. Neither of them knew how to swim. This myth has been debunked. Still. I raise you one: What if all children, everywhere, were taught to swim in their clothes and in open water?

Imagine the look of horror on a Manhattan parent’s face (mine) if a child were to bring home a slip to be signed, granting permission to swim in the Gowanus Canal during phys ed class. If swimming skills are predicated on a basic fear of drowning, they can also be used to prove the water quality of a civilized society. A child who knows how to swim should not then be poisoned by the water. It’s like a game of Floor Is Lava. But real. Now imagine if that signature were dashed off with a kiss on the head and a “sounds like fun, honey.” I can dream. I dream of drinking from lakes the way Augustus Gloop greedily gulps the chocolate river in Willy Wonka’s factory. I wish Biden dreamed of water as Kennedy did of the moon.

indelible swim iv

Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, pulling off the side of the highway, clambering up the dunes because the waves look too good not to jump into them. Cold, loud, crashing waves. The man I am with, an Australian, is completely at home in ocean waves. He strips and walks straight in, without hesitation. We’re there to see Kitty Hawk. We run the length of the Wright brothers’ famous twelve-second 1903 flight—120 feet—in the spitting rain.

Early in Waterlog, Deakin swims the Green Bay in the Scilly Isles, seeing stone walls beneath him. “I was going back four thousand years, soaring above the ancient landscape like some slow bird,” he writes. “And it reminded me how like the sea a field can be; how, on a windy day, silver waves run through young corn.” He compares swimming to flight. One of Deakin’s most popular quotes is in fact from T. H. White’s The Sword in the Stone. Merlin turns Arthur into a fish and says: “There is practically no difference between flying in water and flying in the air.”

Any confident swimmer knows this feeling. But Deakin continues to connect Darwinian dots. In a chapter called “The Red River,” Deakin cites the marine biologist Sir Alister Hardy and the writer Elaine Morgan’s aquatic theory of human evolution, which holds that humans spent ten million years of drought “evolving into uprightness as semi-aquatic waders and swimmers in the sea shallows and on the beaches of Africa.” Hardy had noticed that vestigial hairs formed different patterns on humans than they did on other apes, and that the hydrodynamic lines that would form around a human swimming in a water tunnel would match the lines created by the body hairs—“just what you would expect to find in a creature evolved for streamlined swimming.”

In each body of water, Deakin introduces us to wonderful, marginal characters like Hardy or Sir James Lighthill, a mathematician, preeminent in wave theory and fluid dynamics, who backstroked around the Channel Islands. More familiar figures appear too. He mentions Virginia Woolf in Byron’s Pool, Cambridgeshire; George Bernard Shaw with salt water in his beard; George Orwell on Jura. He name-dunks, then cheerfully explains the politics, science, and history of the landscape he peers at—over and beneath the waterline.

The assignment of this review coincides with a stay in a one-room cabin lent to me by friends, in upstate New York. After spending the previous year landlocked, street-locked, apartment-locked, and finally confined to bed by illness, I’m giddy to be in nature. I walk and walk and walk and poke at birds’ nests and carry attractive rocks across fields and burn through piles of firewood and collect sticks. Seeing a beaver in a neighbor’s pond feels like spotting a UFO. It’s March, but I take off my boots and wade into a river.

I play Poohsticks with my daughter. We each choose a stick, and on the count of three, throw it over the upstream side of a bridge. We run across to see whose comes bobbing along in the current first. Sometimes only one appears. We wait for the other stick to follow, but there are times it never does. So we walk on, suspense fluttering away in the breeze, figuring that it got stuck in some bramble or flotsam. Later, when I’m slicing an onion or stoking the fire, I’ll think of that stick at the mercy of the water.

The sticks that disappear under the bridge sum up this pervasive subtraction—the invisibility, the uncertainty and loneliness—of the pandemic. My own stoic feelings of worthlessness. Friendships have floated. I’m guilty of drift, too. During lockdown, society is a dry riverbed, an oxbow lake, cut off from the source. My natural reclusiveness thrives. I’m happy when I can hear my daughter in the same room, burbling, breathing, asking me to do things for her. “Mom, can you. . . ?” I encourage her to do these things herself. I look up river and water terminology that might describe this pooling of dependence breaking into its own movement. Child as distributary. River deltas of resistance. Family as groundwater. There’s a Heimweh to a hillside in the half-dark of the country, the “dimmit-light,” as Deakin calls it. Just a glance as I drive past, then a flash of riverbed. How can a landscape that I’ve never seen before make me miss my own life?

indelible swim v

Georgian Bay, Ontario. I am eleven. My father has bought a twenty-five-foot sailboat. It is a rusty red, its name painted in black italic on the hull: Abegweit. The previous owner told my father that Abegweit is a species of bird. Later I look it up, and it seems it’s not a bird but another spelling of the Mi’kmaq name for Prince Edward Island, meaning “cradled on the waves.” We sail, then anchor off an island called Giant’s Tomb and swim off the boat, into water twenty feet deep, and clear. I can count the ribs of sand on the lake bed, like rows of rickrack ribbon.

As I sit typing in the cabin, I hear a high pulsating beeping sound, like some kind of alarm. I sit up, then realize it’s the fire. One log—orange, black, and white—is so hot that its whistling is accelerating into the digital. I poke it until the wood ignites and the noise bursts into a less neurotic, muttering roar. I stare at the fire and think of Deakin’s words in Wildwood, his second book—this one about trees—published posthumously in 2007: “As it burns, wood releases the energies of the earth, water and sunshine that grew it.”

When I was in third grade, my suburban Catholic school sent thirty of us into the woods on an overnight trip. We learned how to make a fire from wet grass and prayed in the snow, but what I remember best was the animal survival game. Each of us was assigned an animal in the southern Ontario food chain, starting with trout, then on to chickadee, to small mammals like raccoons, to predators like wolves, hawks, and bears. One kid got to be man, and four children were elements: fire, flood, famine, and drought. I was a squirrel. A jealous one. Of course I wanted to be all-powerful water or famine. Everyone did. The point of the game was to acquire punches on a card, at food stations hung from various trees throughout the woods, without getting eaten—i.e., having your card taken by someone higher up the food chain. I got killed off early on by a wolf (Julie) who plopped herself down on a log near one station, waiting for the rodents and birds to approach. When you died you convened in “God’s land,” a perch above the ravine, where the hollering of fresh kills would echo up to us dead little animals.

That night, in a row of iron cots occupied by little pizza-fed nine-year-old bodies tidily arranged beneath a crucifix, I knew my very small place in the order of things, even as man.

This memory comes back to me as I stare into the fire. I think: Deakin was fire and Deakin was flood. I am probably still a squirrel, a black one with a raggedy tail, like the ones you see, freaked out, in Toronto parks.

indelible swim vi

Warren Falls, Vermont, Fourth of July weekend. My daughter wears a life vest and we wade from pool to pool, spotting members of the wedding party along the boulders. The water is cold, and she is apprehensive of the rocks and the darker water in their shadow. I’m distracted by messages from a psych ward, emphatic proposals of marriage. They warp the vows I heard the night before, my daughter dancing to Bowie. We find a bend in the river where our friends have spread towels around a deep, pebble-bottomed pond. I turn off my phone. We swim and get out to dry in the sun, and repeat this until we get hungry. On the way to the car my daughter stops to examine pollywogs in a shallow stream.

One odd thing that dates the book—in a good way—is its lack of foodie fetish. Waterlog came out a hair before the boom of farm-to-table, nose-to-tail foodie culture and the celebrity of chefs such as Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall and Fergus Henderson. Deakin describes a meal as getting his “head in the trough.” When he mentions food, it is “some chocolate,” “tea and wine,” or “another cheese sandwich.” I do wonder if, in the intervening time, The Great British Bake Off made the U.S. publication of this book easier. Waterlog is very English. Quite English. Gogmagog this, beck that, eel jelly. I am an Anglophilic Canadian, once married to a British man, so the deep Englishness of Deakin’s subject matter and delivery is familiar to me. The absence of gastronomic detail feels radical, but he applies nuanced, juicy notes to frogs, lichen, and damselflies instead. He puts his face to the ground, his cheeks in the loam. A lot. He lies in the grasses and they steam up his spectacles, and he listens. Often naked. Deakin likes to be naked.

The book is quietly erotic. Its sensual bass line isn’t food or companionship (though a love of his son and friends is obvious), it is wood and water. In Notes from Walnut Tree Farm, which is organized by month, a February entry reads:

What you need to write is energy, sexual potency and solitude. Swimming gave me plenty of all three, stimulating the hormones as it sharpened up the stamina, and isolating me with one of the great universal elements.

His descriptions of swimming are salty and intimate.

Throughout its thirty-six chapters, the structure of Waterlog emerges as a river system, where the organizing principle, as it is with water, is gravity. Deakin’s level is that of simple common sense: conservation is our responsibility. The health of the natural world is the health of our own family. I read his chapters the way he swims—meandering, drifting—rapt by the natural history and animal anatomy he shares like an endless bag of fat pistachios. His stories and alphabets feel like currents; I let them take me to places of my own, to pools that lead to other rivers. “Left to itself, a river will always meander.”

I think of water finding its level, of stories coming to light. Postmemory. How telling and shame have evolved. Abuses and their scars, made on humans or land, are no longer protected or ignored. Telling is, lately, a burst dike. Stories coming out from under pressure, digging in, pushing back.

Dotted throughout Waterlog and Notes are references to the popular Geoffrey Household novel Rogue Male. In it, a fugitive almost-assassin escapes detection by fleeing, crawling around on his belly, and hiding in rural England. In an introduction to the 2007 edition, Victoria Nelson attempts to categorize it—perfectly, in my opinion—as a “wilderness procedural.” Reading it offers insight into Deakin’s own apparent mix of adventure, persecution, and sportsmanship.

Photos of Deakin: A chiseled, lined face, Barrymore chin, shock of curly white hair. A cross between Christopher Lloyd as Doc and mid-career Malcolm McLaren. Is Deakin a Rogue Male? He’s not domestic, but he’s devoted to his camp. I wonder if Deakin might be an example of . . . tonic masculinity? He approaches confrontation. He defends and protects. He’s a conservator and a builder. His subversion isn’t cruel or powerful; it’s based in freedom and husbandry. Thoreau’s civil disobedience. He wouldn’t stand there staring at a Big Two-Hearted River; he’d strip down and swim up it. Deakin, when he realizes that the River Lark, the “Jordan of the Fens,” has been funneled into a concrete canyon to make room for a supermarket: “By the Bury St. Edmunds Tesco I sat down and wept.”

Despite his love of nature, he isn’t a spectator, doesn’t go with the flow. In his three books, Deakin rhapsodizes on trees, wood, and animals, and rails against the poverty of imagination, of foresight, of the unavailability of the Australian poet Les Murray’s books in Britain. He’s outraged at English xenophobia, at the eradication of the coypu. He also rails against “proper swimming” and the privatization of water; against I’m a Celebrity . . . Get Me Out of Here!, where “eating five plates of ‘creepy-crawlies’ . . . actively alienat[es] nature.” He’s suspicious of the heritage industry, which he feels tames the wild “to death.” “You can always tell something untoward is going on in a place,” he cautions, “when you see large numbers of trees being planted.”

Deakin’s first swim in Waterlog occurs in April. So I decide to try one then, too. Two swimmer friends mention a pond they know, a half hour’s drive from the cabin. It’s pouring rain, but the forecast predicts snow later in the week. I make a thermos of tea and pack a towel. The road along the waterside is empty; we park, undress, wade in. The pond is very cold. Its surface is steel-gray, prickled with rain. The bottom is unstable and soft: mud, leaves, and sticks. I push off, shoulders in, and breaststroke out. The water is brown, dark breakfast-tea brown, and smells strongly of mulch and wet wood. I splash around a bit, and then, feeling my hands start to go numb, I get out. My hair is still dry, and I decide to get back in, this time diving beneath the surface, feeling the water, like being swatted with a boar-bristle brush on my face, neck, and scalp. I drive home, blasting heat and Taylor Swift. The rental car smells wonderfully mucky.

There is a 1996 book by the artist Tadanori Yokoo called Waterfall Rapture: Postcards of Falling Water, which features nearly thirteen thousand postcards of waterfalls over nearly three hundred full-color pages. No captions. Just water—crashing, trickling, falling, over and over, all over the place. These vernacular pictures of moving water, arranged thus, animate and pause. The accumulated images feel like unified time: the same thing happening everywhere, forward and backward and vertically. The past and present overflowing, all at once.

In Notes from Walnut Tree Farm, Deakin traces his passion for conservation to the death of his father, when he was seventeen. “I was wanting back what I had lost . . . I didn’t want to lose anything more.” At the heart of his work is the balance and flux between holding on and letting go. Roots and spores. Sleeping in his Citroën (with its hydropneumatic suspension) and sleeping in his bed. The indelible and the impermanent. Stay, stay stay, go, go go. But in every chapter, in every book, there is the deep idea of habitat. Of living, in a living place, with—not on or off—the place, which more creatures will inhabit, love, and then leave. It makes me think of Blake (the hippie) again. Devotion, enthusiasm, eternity.

My favorite Deakin swims are his moat swims. Toward the end of the book is a chapter called “Swallow Dives,” just over two pages. After he finishes a moat swim, Deakin wants to light a fire but is prevented by the swallows, who “return to the chimney nests each night, chattering long after dark, like children in a dormitory.” He wishes they’d leave, but catches himself. “I remind myself that I’m a mere newcomer to this ancient dynasty of nomads,” he writes, “who settled here centuries before I ever appeared on the scene and will, I sincerely hope, long outlast me here.”