Illustrations by Matt Rota. Source photographs courtesy the author

I landed in Barrow, Alaska, on a bright June night. The flight had been long, with a stop in Minneapolis, a layover in Anchorage, and another stop in Prudhoe Bay before my arrival at Wiley Post–Will Rogers Memorial Airport. It is as far north as Alaska Airlines flies. The sun had risen a few days ago and wouldn’t set again for weeks.

This all happened near the end of the two centuries during which the town had been known as Barrow. In the fall, the town would vote to change the name back to Utqiaġvik. The place had been known by that name (or something like it) for hundreds of years prior, long before white whalers and explorers started showing up and naming things after themselves. But the vote would happen later, after I left. On the day I arrived, my plane ticket said Barrow. The signs said Barrow. Everyone called it Barrow. So this part of the story happened in Barrow, a town that does and does not exist anymore.

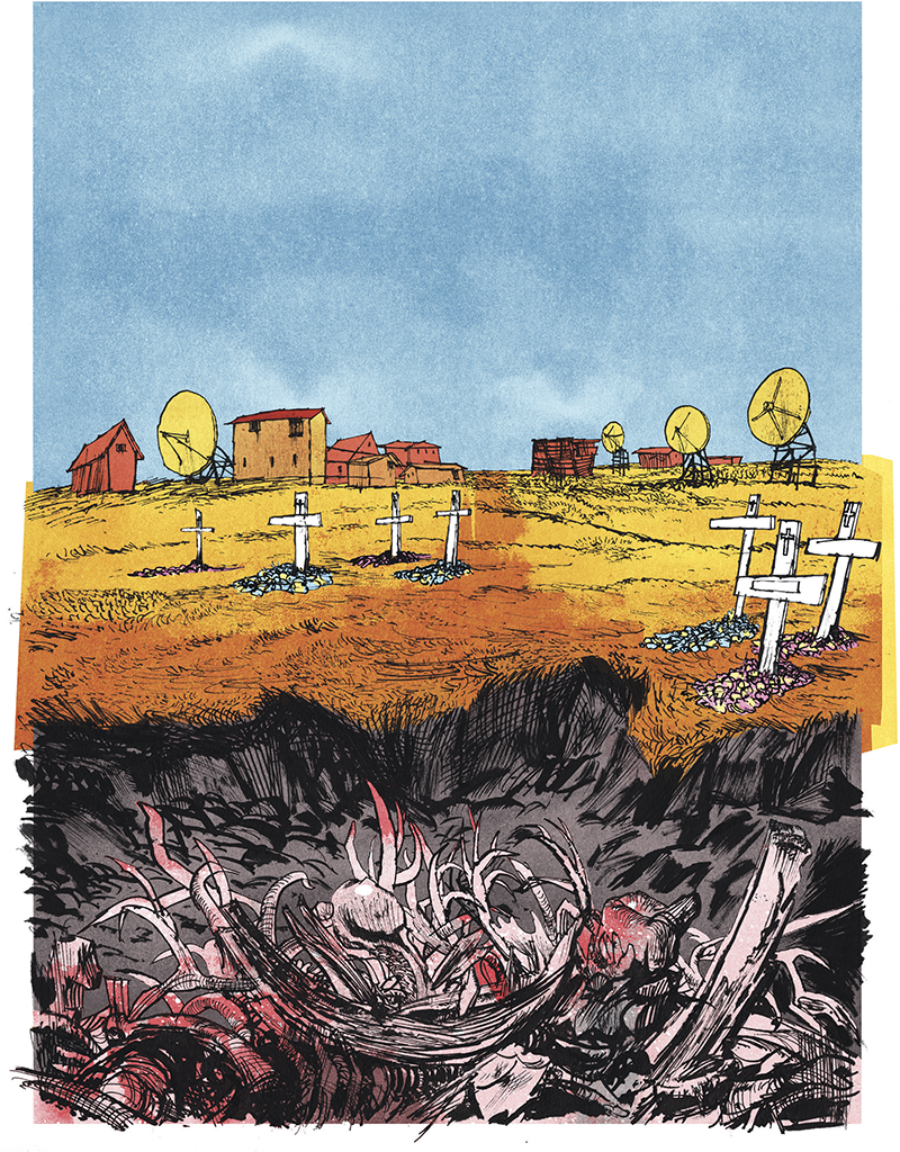

On the southern edge of town, where the road meets the open tundra, there is a cemetery. It is an uneven place. The graves are lumpy and round and wide, and the white crosses that mark each body are crooked and have settled in such a way that they point in contrary directions. In the winter, the ground is frozen and must be broken with augers to dig a grave. In the spring and summer, after the sun emerges from the arctic night and the snow melts, the ground loosens a bit and digging can be done by hand. It is one of the most colorful places in town, full of bright artificial flowers and makeshift memorials and handmade decorations. The bodies buried here freeze in the soil before decay can begin. The dirt placed on top will never quite flatten out. The rolling piles of dirt and old grassy mounds offer evidence of the people below. Eventually, the cycles of the frozen tundra will swell the ground, heaving many of the graves up even higher, as if the bodies are being rejected. The land does not want the past to be buried.

Tourists come here every year to see the northern lights or watch for migratory birds. Some hope to glimpse a polar bear before the species goes extinct. I’d come because I wanted to eat a whale.

From the graveyard, the road into town leads past a field of giant satellites, huge white dishes that bring in the rest of the world: phone service and weather reports and television channels. In most places, satellites point up, toward the sky, but here they point straight ahead. In this place, about as close to the North Pole as one can live, you need only look over your shoulder to the right and there you can see it, the end of the earth.

Beyond the satellites, the road passes a gravel pit. It is a cliffside operation that puts out pearly black pebbles by the ton. Every year, when the melting waters of the Chukchi Sea take more land from the coast of Barrow, dump trucks of gravel will repair whatever holes they can fill. It is a failing operation. The town gets smaller every year, but the gravel trucks do what they can.

Outside the airport, the wind was whipping my face, freezing cold, and the sun was high up in the cloudless sky. I squinted, couldn’t see through the glare, put on sunglasses. A beat-up Toyota rolled down the road and I waved him over. He took me to a restaurant called Northern Lights. I was tired and hungry and the waitress brought me a thirty-dollar plate of chicken bulgogi. The driver hung around, said he didn’t have anywhere else to be at this hour. He was from Myanmar, had been here for a few years, didn’t speak much English. He drove me down a long road to a rusted Quonset hut on the edge of town. I’d rented a room there, but no one was home. I found a key to the front door in a pickup parked out front. I lay down in a bed I figured was mine, tried to close the blinds and shut out the night sun.

I didn’t sleep well. The blinds were no help. I woke several times, disoriented by the bright sky, unable to tell whether it was night or morning. I made coffee and put on gloves and wandered around in the cold.

Barrow is on the coast of the Chukchi Sea, about three hundred and twenty miles north of the Arctic Circle. It is a narrow town—only as wide as the airport runway is long—that runs down the cold dark coastline until it disappears. The land slopes northeast, about a thousand miles shy of the North Pole. The roads have been laid cockeyed to the coast and are interrupted by a handful of lagoons that separate the town’s three main districts. Owing to this odd municipal grid, there is no single main drag, though Stevenson Street comes close. The roads have never been paved. They are simply packed dirt, like the paths of any town still on some kind of frontier. The town’s oldest buildings are clustered together near the Utqiaġvik Presbyterian Church, marked with a whalebone sign dated 1898.

They are wood-frame houses and steeple churches roofed with tar shingles and painted simple colors: white, blue, green. They look like they belong in New England. Squint and you can see a rough, flat Nantucket. Flower beds are scarce here; pansies do not thrive. The yards are gardens of the past. There are tangles of caribou antlers stacked like dead branches on Pisokak Street. Dogsleds, their old wooden slats long broken and faded the color of slate, lean up against the houses one block over on Okpik. Barren umiaks, stripped of the stretched sealskins that once made them float, lie about like skeletons. Frayed ropes are everywhere in knots and coils. Every home has a menagerie of hoists, blocks, hooks, bones.

It is not true to say that there are no trees in Barrow. In a yard off Stevenson Street, there is a steel pipe with baleen attached to it like palm fronds. The man who lives there likes to tell a joke: “Here in Barrow, we’ve got a beautiful woman behind every tree.” He put up his homemade palm tree, the only tree in town, so that his wife would let him keep telling it.

On the other side of a couple lagoons is Browerville, the part of town built mostly after its namesake, the whaler Charles Brower, died in 1945. You can see it in the shapes of the buildings. The three-story Top of the World Hotel, where tourists come to see the northern lights, sits next to the squat post office, where the tourists send postcards with pictures of polar bears. The wide parking lot and familiar big-box Alaska Commercial grocery store could be anywhere: Bloomington, Tampa, Portland. The prices are higher here, though the food is mostly the same: bags of lettuce, boxes of strawberries, sixty-count portions of frozen breaded chicken strips.

The third part of town, past more lagoons, is or was the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory. Though it closed in 1981, everyone here still calls this area NARL. The road that runs through it is still known as NARL Road, and the buildings that NARL built are all still here. The idea was a simple one: whatever it was that was happening out here on the edge of the earth needed to be studied—the soil, the weather, the wildlife. They put up Quonset huts and hangars and dorms, brought in scientists. Eventually, the Navy gave the land to the local tribal corporation, a gift to the people they’d stolen the land from in the first place. A small college operates on the property today.

Here, almost hidden at the far edge of town, the Air Force built part of the western end of the Distant Early Warning Line. When this radar was installed, shortly after the end of the Second World War, the technology was new and served only one purpose. It was here in the Arctic that everyone expected the planes to come flying in from the USSR. They would be carrying nuclear weapons to drop on our major cities, which would trigger a chain reaction around the world, which would ultimately be reduced to cinders. Whenever it came, the end of the world would begin in Barrow.

I reviewed restaurants for years. It wore me out. I had become accustomed, as many restaurant critics do, to having my tastes endlessly catered to. I only noticed when they weren’t. It was a kind of confusion, my belief that the things I wanted from the world could be ordered as if they were items on a menu. I believed I was writing a book; I believed it would contain everything I wanted it to contain. Though I quietly allowed the distinction of my taste to somehow justify the obscenity of my privilege, I can see now that I had lost the ability to discern what my tastes revealed about myself.

I had been doing this work long enough to grow weary of culinary illusions. I no longer liked dishes that depended on tricks or anything too clever. Culinary trompe l’oeil bored me. I was beginning to understand that our food culture had become obsessed with, in fact desired, being fooled. I wanted to look the animal in the eye. I had not yet recognized that I was fooling myself, that my own illusions were the ones preventing me from finishing the book, that I had confused my ability to gather facts with the very different task of understanding them, that I believed the work to be nearly finished when it had hardly begun.

I was interested in some of the conventional questions—Why do we kill animals and why do we eat them? Is it right or wrong? What constitutes ethical behavior in a godless world?—but I wasn’t deluded enough to believe that I would find their answers. I had read all of the books that claimed to have them, and I hadn’t been convinced. I thought I could settle for how instead of why: How do we kill animals? How do we eat them? Those were questions with answers. I thought the facts could be enough.

There is an alternate definition for meat, one that simply means the thing inside of the thing—i.e., the meat of a coconut or the meat of a problem. My inquiry aimed to understand the living, the dead, and the part in the middle as well, the thing inside of the thing. I’m trying to tell you why I had finally resolved to taste whale.

When Charles Brower arrived here in 1886, there were no stores, no farms, no butchers hawking meat by the piece. Yet, by his account, life was good, food was plenty. You put your line in a bay and pulled out a week’s worth of fish in an hour. Flocks of migratory birds passed by in such numbers that this place was named for it. Ukpeagvik means “the place to hunt snowy owls.” The Iñupiat people had lived and eaten well for centuries before Brower came around. In the backcountry caribou were everywhere; you didn’t even need a gun to hunt them. Locals had built a simple trap: two wide fences made from piles of sod and pillars of black moss that narrowed to a lake. Anytime a decent herd of caribou came along, a few women and children would spook them down between the fences until they were led to the lake, where the caribou would attempt to swim to freedom. They never made it far: men waited in umiaks to spear the animals and drag the bodies back to dry land, where they would make dinner. Brower had not come to Barrow for a handful of fish or a leg of caribou, though. He’d come for whales.

He found plenty of them. Most of the local folks welcomed him in. They let him join their crews, which still went out into the arctic waters in sealskin-covered boats. He paddled along as they jabbed stone and ivory harpoons at black bowhead whales. He helped pull ropes, hauling their kills up above the ice. He sawed at the flesh, cutting away the long strips of muktuk, until he, like all of the men and women around him, was covered in blood and tired of the work.

Brower was born in Manhattan in 1863 while his father was fighting in the Civil War. He left to work on his first ship at fourteen. By nineteen, he was a seasoned third mate on the C. C. Chapman when it caught fire rounding Cape Horn. The ship’s hatches blew open, flames roaring from a blaze in the coal storage, but the captain insisted that they sail on to San Francisco. By the time Brower stepped onto land, the crew had navigated the burning boat for fifty-two days and six thousand miles.

Brower set out again less than a year later, on an expedition to look for coal on the northern coast of Alaska. There had been rumors of enormous reserves: enough coal to fuel a fleet of whaling boats without the added expense of shipping it north. Their crew found them, black veins up to fourteen feet wide, running through Corwin Bluff. As they tried to mine the coal bed, the cliff collapsed in an avalanche, nearly killing the crew that had come to find it. The expedition was abandoned and the ship returned home, but Brower decided to carry on, by sled, to the northernmost point he could find.

By that time in the Western world, whales had become part of the useful stuff of modern life. Baleen, the thin black filter with which bowhead whales extract their food from water, had been found to have other applications. It was both pliable and strong, a practical material.

Coachmen in Manhattan drove their horses with buggy whips made of whale. The well-dressed woman inside the coach bound her breasts in a corset lined with whale. A man walking down the avenue opened an umbrella to guard against the rain, the ribs of the parasol made from whale. When he arrived home and the woman stepped out from the coach to meet him, they would light a flickering lantern burning with whale oil. On a mattress lined with whale, they would lie together.

Not long after arriving in Barrow, Brower became one the most successful whalers of his generation. He made a fortune in a single season; after several years, he could have taken his earnings back to Manhattan, where eventually he would’ve been feted with parties at the Explorers Club, and retired comfortably far from the Arctic Circle. In his partially fabricated memoir, Fifty Years Below Zero, published only a few years before his death in 1945, Brower explained what happened next.

Corsets went out of fashion. Buggy whips became useless. “Where formerly a good whip with a bone heart had been a smart adjunct to any moonlit buggy ride, young men now chugged their girls around in new-fangled horseless buggies,” he wrote. Everything that baleen had once been used for was now being replaced by a new, cheaper, more practical invention: plastic. Whale oil was made redundant by the petroleum industry. In a few decades, it would be oil men, rather than whale men, coming to the North Slope looking for their fortunes.

When the market bottomed out, Brower quit whaling but stayed in Barrow. He shifted his business, Cape Smythe Whaling and Trading Company, to focus on trapping animals and trading furs. He lived comfortably in a white home with a pool table and a library. He played host to visitors curious about the Arctic. When an anthropologist came looking for artifacts, Brower helped him by hiring a team of local children to do the digging. Eventually, they uncovered thousands of archaeological remains, which were sold to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The children were paid in chewing gum.

Brower mostly ate what the locals called “white man’s food”: flapjacks and eggs, pot roast and sauerkraut. He had oranges and bananas shipped in fresh. Local children had to be taught to peel them; they’d never had a piece of fruit before. Eventually, his trading company became a place to get the sort of provisions that hadn’t been here: cans of milk, bags of flour, boxes of tea, dried fruit. In the end, this was his business. Brower became Barrow’s first grocer.

Out in the cold waters of the Chukchi Sea, there were bowhead whales swimming. Bowheads travel thousands of miles in their annual migrations. The largest among them measure up to sixty-five feet long and weigh more than one hundred and twenty thousand pounds. They glide along, propelled by their smooth, black tails. They eat all day, thousands upon thousands of krill spilling into their gullets. They look for other whales, for mates. They sing long, complicated songs in a language we cannot comprehend. They sing to one another.

It’s true that there are many people in this world who believe that killing and eating such a beautiful, complicated creature is a horrible thing to do. Here on the coast of the Chukchi Sea, that is a plainly foolish opinion. Nothing grows in Barrow. There are no farms. The food sold at the town grocery store is extraordinarily expensive because it has to be flown hundreds or thousands of miles. To live here has always meant to hunt snowy owls, to hook fish, to harpoon whales.

Every year the ice melt becomes more and more unpredictable. The coastline is slowly disappearing. The changing climate will eventually destroy this town, a coming apocalypse only worsened by the jet fuel burned to bring in the bird watchers and nature lovers, to feed them frozen junk. Yet it is instead the whalers here who are vilified by outsiders, the whalers who fear a misguided “save the whales” campaign might end their seasonal allotments. As if it were somehow better to eat from bags of frozen chicken flown in from Arkansas. This is a cruel irony.

I suppose I’d come here in part to write a story that explored some of this. I wanted to tell people that if only we could eat more like the whalers in Barrow, sharing the food of our own communities, we’d probably be better off. Something like that. But I knew it wouldn’t really matter. It would irritate the people who lived here and it would irritate the people who lived far away. The world would go on continuing to end.

Analukataq was scheduled for the day after I arrived. When the ice begins to melt and it is unsafe to go out into the water and hunt, the whaling crews divvy up their catch from the spring season among any community members who care to attend. That’s a nalukataq.

Andrew, the man who was renting me a room in his house, asked me to collect a share of whale, if I was already planning to stop by. Anyone can go, he said. He was right. I walked down to the beach and sat on the tarp where everyone else in town was sitting. The friendly people next to me asked who I was and where I’d come from. I said I was staying in Andrew’s house in NARL and that he had asked me to collect a share. They said, “Oh, of course, Andrew.”

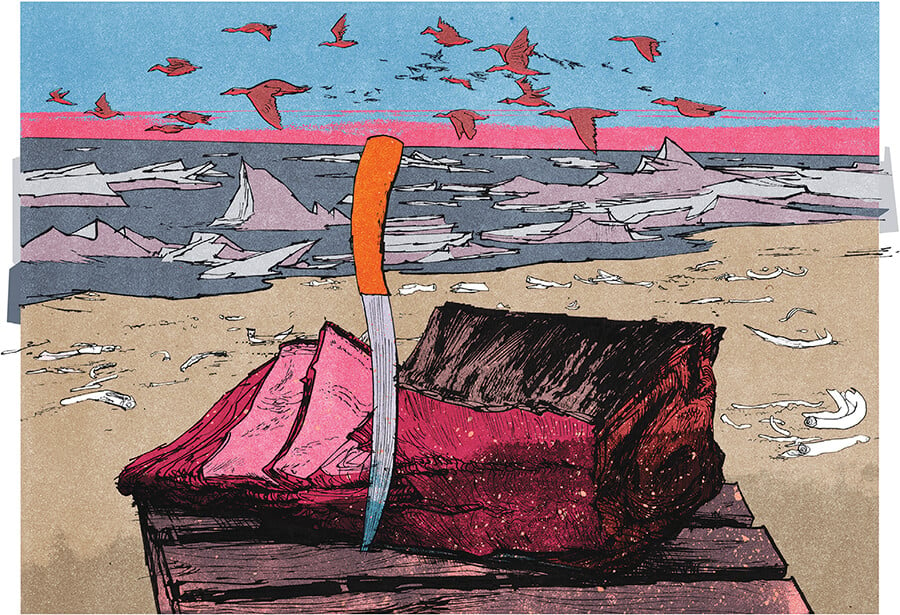

A little while later, a woman with a microphone said a prayer and sang a song. Children poured hot tea into my thermos. Big pots of goose soup were carried around and ladled into bowls. Eventually, the whaling crew brought their whales to the beach. Before this day, they had spent hours and hours chopping and sawing these giants into small pieces that could be evenly divided among the crowd. They carried in dozens of white cardboard boxes, each stuffed with pieces of whale. They rolled in barrels filled to the top with long strips of whale. Everyone sat patiently as the captain gave directions. Three pieces of meat for everyone. Three pieces of fat for everyone. Three pieces of dried liver for everyone.

As the crew patiently walked through the crowd, counting out each scrap so that everyone would get a fair portion, the people sitting next to me were kind enough to explain how I should eat. When the meat was handed out, they told me to eat it raw. They’d come prepared with paper plates and handed me one. I sliced into the dark-red, dense flesh and put a sliver in my mouth. It was bloody, like fresh beef, but it tasted oceanic, rich with the salt and funk of the sea.

After that came strips of fat, which they said were best to save for cooking. Then came a bucket of something dark and sludgy. My neighbors explained that this was meat and fat and skin that had been fermented in blood. They said to cut the blubber into very thin strips to make it easier to chew. The flavor was intense, more potent than any aged meat I’d ever tasted. It gave me the sensation of being completely satiated after only a few bites.

The children came back around, refilling every cup with tea. The crew handed out pieces of fried bread and fresh oranges. The people around me thought that was very generous, giving everyone an orange like that. It was a polite and friendly meal, not unlike a church potluck. I think that before I’d come, I had vaguely expected to see a whale, or at least most of one, sitting up on the ice. I’d come the wrong week if I wanted to see the whole thing. Before I had arrived, I’d watched some footage. Harpoons darting through the air; blood brightening the black water; whales diving under for their lives; white lines pulling them back up. The process is not unlike a bullfight: a large body being slowly worn down, bled and exhausted until it acquiesces to death. I saw none of that while I was there. The killing and eating were kept separate. The whale I ate that day looked the way meat always does: cut up into the small pieces we can handle.

In the evening, I brought back the share of whale meat and fat that Andrew had asked me to pick up. I lay awake in bed, the midnight sun shining in my window, wondering again why exactly I had come to this place.

The next morning I met a man named Joe who promised to show me his museum. The museum was a two-story house overlooking the Arctic Ocean. I arrived before he did and stood in the yard. It was a garden of old things: caribou antlers and flat tires, ropes and chains, harpoons and hooks, dried-out bearded sealskins sewn together, and whale bones piled up all around like oak branches. The wind was burning my face and gray clouds had come in to hide the sun. I was just about to give up and leave when Joe came limping along the road to let me in. He was small and frail, with graying hair. We climbed up a narrow staircase on the side of the house. I walked behind him, unsure if he would fall, and he began to talk.

“I delivered water around town with two trucks for twenty-eight years. I did that till 2002 and now I don’t work anymore. Four years ago, I had a bunch of strokes and they medevaced me to Anchorage and I was unconscious for eleven days. The doctors were in the room ready to unplug me when I woke up. I don’t work anymore now but I’m doing okay. I don’t stay here anymore. I’d like to stay here.”

He unlocked the door to the second story and, as it slowly swung open, I could see why he couldn’t live here anymore. The entrance was a passageway into a labyrinth of animals. A polar bear was posed with its mouth open, teeth bared. Another one was reduced to a rug, its head peering up from the floor. A wolf narrowed its eyes from behind a shelf. A caribou, an elk, a ram with its horns grown in thick spirals. Long-tailed foxes and skinny marmots. A howling coyote. They were all frozen still in this dim room, hardly lit for all of the silhouettes and shadows cast by the menagerie and the shelves they had been collected on, almost impassible but for a couple of paths. The museum had outgrown him. There wasn’t room for him anymore.

“The animals in here are arctic animals. Make yourself at home. Take pictures if you want and ask questions. Sorry, nothing is for sale.”

I mostly didn’t have to ask questions. He kept talking as I tried to understand this place, the thing he called a museum. It was almost possible to imagine when it had been a simple collection. Back against the main wall, there were a few bits of whale bone and small animals on a shelf. In a side room, there were glass cases stuffed with rusted metal and worn-out wood. They looked like they could be pieces from the whaling boats that the Yankees had brought here a century and a half ago. Maybe.

“I was pretty broke when I got here and wanted some stuff, and there was stuff for sale around town but it cost more than what I could deal with. So I went to the beach and found a bunch of bones and different things, and I just ended up collecting a bunch of stuff from the beach and wherever,” he said.

It was hard to focus on any one thing, because in front of every one thing, Joe had positioned another. In front of one shelf of animals, he’d built another shelf and put animals on that one, too. There was so much more: Carling Black Label beer cans, McDonald’s Big Mac containers, broken guns and framed newspaper clippings, paintings and photographs, skins and feathers and carvings.

Joe explained that forty years ago he had come here wanting something simple. He wanted to see a polar bear. He could not explain why he wanted to see a polar bear. He just said he was young and that was what he wanted. And soon after he wanted something more. And again and again.

This is what happens when you want to understand, when you try to know everything you can know. It is a beautiful temptation, to collect from the world and arrange it so that the collection reduces the world around it, so that things around us that were once unexplainable and unknowable can now be seen clearly with a single glance. This is what maps, museums, books, and farms try to do. They try to make the world comprehensible. They organize nature. This is what I wanted to do, I suppose. The trouble is that the world isn’t reducible in that way, it can’t be understood at a glance. It can’t be made a single inch smaller than it is. Yet we insist on trying to understand. It is a simple, human desire. We keep adding to our arrangements, to our museums, animal after animal, bone after bone, until there’s no more room. What’s left behind isn’t as big as the world, and somehow much smaller than the mystery that surrounds it. The failed collections of broken men. Dim rooms full of junk.

On my last day, I walked around aimlessly for some time, standing out on the beach taking photos of what would’ve been a sunrise if the sun had ever set. I walked between the old houses. I drank some coffee. I visited the graveyard and took pictures of the fake flowers. I couldn’t have told you what I was looking for. I was walking down a dirt road when a man in a rusty red pickup stopped and rolled down his window.

It was Abel, Andrew’s neighbor, whom I’d met at the nalukataq a couple of days before. He asked me if I wanted a ride, said that he was going to pick up some water, would I give him a hand? I said, Sure.

“You said the other day you’re a writer. What kind of story do you want to write? What do you want to know?” he asked.

I told him that I’d come here because of the whales, that I wanted to eat whale but that I also wanted to know more about it, that my job was mostly just going places and asking people questions and writing down what they said and did. I said I figured I should talk to a hunter, someone who could tell me more about killing whales and eating them.

“Are you a hunter?” I asked.

He said he’d been hunting his whole life.

“Could you tell me about the whales?” I asked.

“I don’t really feel like getting into all that,” he said.

I was relieved, to be honest. Sitting in Abel’s truck after visiting Joe’s museum, I didn’t want to be the guy who was just here to get something from someone else, to add it to my little collection of notes.

We stopped and picked up some water, and I helped him load it in the truck. I figured he could drop me off wherever since I wasn’t really going anywhere.

But he said, “Let me show you a place.”

He drove his truck down to the end of the road, past the Cold War runway, past the dark-blue football field, and past the camps for hunting ducks, until the road gave out in a dusty circle and all we could see was a long strip of gravel leading out to the horizon, melting ice on either side. Between us and the point there was a sign posted: no trespassing. He said this was as far as he could take me.

“Out there, past the sign, that’s where we go, where I’ve gone every year since I was old enough to stand,” he said.

We sat in silence for a little while until he spoke again.

“What you should write about is the lineage,” he said.

I didn’t understand him at first. I couldn’t hear the word, so I asked him to repeat it, but even when he said it and I heard it, I didn’t understand what he meant.

“What’s the lineage?” I asked.

He said the lineage was the way he’d been taught, the way he’d gone out there and learned the same thing his father had learned, that his father had learned the same thing his father’s father had learned, and so on.

“So what do you learn out there?” I asked, pointing out at the gravel disappearing into the horizon.

“The first thing you learn is how to make tea,” he said.

After a while, he turned the car around and dropped me off back in town. That night, I decided to walk past the sign.

Andrew’s house had filled up with research assistants talking about their latest plans, satellite transmitters on bearded seals, population counts and white papers. We had a little potluck. I made a salad with ingredients flown in from California: limes, avocados, cherry tomatoes, butter lettuce. It cost a small fortune. Andrew made two courses of whale. For the first, he sliced raw muktuk into perfect little rectangles, the size of sashimi, and sprinkled them with Old Bay. The fat melted on my tongue. For the second, he braised a hunk of whale meat in its own juices in a slow cooker until the whole house was steaming with that oceanic smell. The strands fell apart like tender stewed beef. We sipped from a bottle of whiskey I’d brought in on the plane.

Around midnight, I said I still hadn’t seen the point. That I’d only stopped at the no trespassing sign. I said I wanted to see whatever was on the other side. I guess I still thought that I’d come here to find something, to have something I could leave with.

A couple of the assistants said they’d come with me. Polar bears were known to prowl out there, they said. It wouldn’t be safe to go alone. They brought a shotgun. Andrew dropped us off at the sign, and we started to walk.

I’d bought special boots for this trip. They were shin high and waterproof and steel toed and heavy in the heels, and as we stepped out into the gravel, I watched my foot sink deep into the rocks with each step. I had to pull each foot up, one after the other.

The clouds had come in thick and the wind was strong. The assistants walked ahead, one with his hand on the gun. For an hour or so, this was all we did, put one foot in front of the other, dragging them through the gravel. It was easy to feel as if we had stepped out of time altogether, that it was both day and night, yesterday and today. The mind wandered. The strip of gravel we walked along grew narrower and narrower. We could see how the rising waters on either side might swallow it any day. We could see this was a place where the world would begin to end.

When we got to the end of the earth, we found a boneyard scattered with pieces of whale. There were a few fresh bones, ribs still stuck with pieces of white fat and blood, but mostly there were old and weathered remnants, bones turned gray like stone. They seemed ancient. The bones were everywhere in piles and stacks, long thin ribs and thick old spinal columns and skulls sinking into the gravel. All through them were more recent things: bits of driftwood, potato chip bags, rusty cans, and soda bottles. Plenty of trash. An old boat. The midnight sun came out from behind the clouds and the ice glistened.

We stood there and watched the melting ice float by. I was searching that night. I still believed I could find it. I listened closely and saw everything my eyes could see. I tried to feel what I could with the numb skin on my face. The wind whistling past our ears, the sun glowing on our heads, the bones crunching beneath our feet. And like every other time, there weren’t any words. Nature offered the answer that nature always does. I wrote nothing in my notes.