The Portrait Gallery

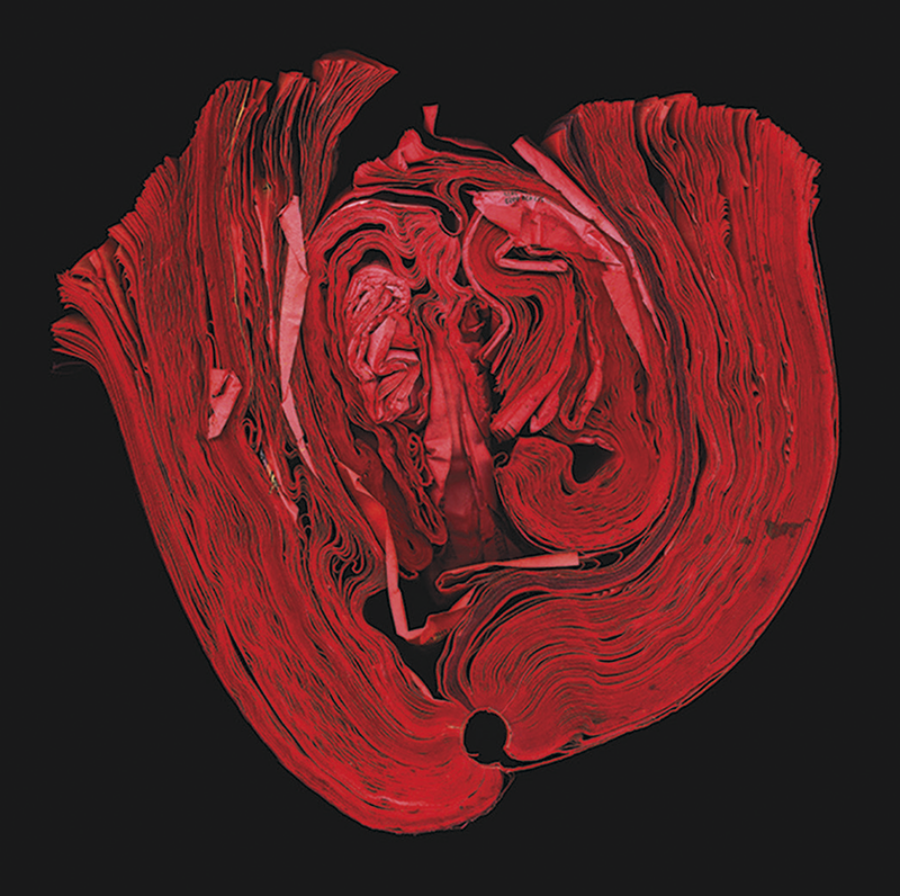

“Heart,” by Cara Barer © The artist. Courtesy Klompching Gallery, Brooklyn, New York

I went to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2005 because I’d won a writing prize, and with that prize came an invitation to a luncheon and awards ceremony. Each honoree was allowed to bring a guest, and I invited my friend Patrick Ryan. We boarded the subway downtown and took it all the way to 155th Street, he in his summer suit and me in my best dress. I’m not a New Yorker by any stretch, and Washington Heights was unfamiliar to me. The Academy’s Beaux-Arts building, the long, sloping hill of Trinity Cemetery, and the view of the Hudson River made me feel like we’d caught the train in Kansas and resurfaced in Oz. Writers and artists and composers were coming toward us from every direction, people whose work we’d committed to memory and whose faces we knew on sight. The day was windy, and Patrick and I were so nervous we ducked down a few stairs beside the enormous building to smoke. When we finished our cigarettes we were brave again.

I have such fondness for that memory, that moment, as that would be the summer I would quit smoking for good. No more cigarettes for courage while staring into an elegant cemetery. I had known very little about the Academy before we got there, and understood nothing about how the place worked. At the registration desk, I gave my name and received a program and our table number. Someone introduced me to Tony Kushner. Tony Kushner! While shaking his hand, I asked him whether he had won a prize as well. He told me no; he was being inducted.

“Am I being inducted?” I asked. Everyone around us laughed. Who knew I was so funny?

I’d been invited to visit for the afternoon. I hadn’t been invited to stay.

Patrick and I went to look for our table like a couple of middle-schoolers who find themselves in the MIT cafeteria by way of a dream. We located the table and then looked for our place cards. I was seated next to John Updike.

When I was young, I read the books that were available, not the books that were appropriate. I read what my mother and stepfather left lying around, which meant that I read Updike. His sentences, his characters, his imperatives filled my brain when my brain was soft and at its most impressionable. Along with Bellow and Roth, he was my influence, the person who had made me want this job in the first place, the person who (I believed) was showing me what adult life would look like, what sex and love and work would look like. He stood up to greet me. Of all the things I ever imagined might happen in my life, sitting next to John Updike at a luncheon on the terrace of a Beaux-Arts building beneath a white tent at a table full of flowers was not among them. Lore Segal was seated there, as were Calvin Trillin and Edmund White. Updike asked whom I had come with, and when I told him, he winked at Patrick from across the table.

Updike could not have been kinder or more charming. In a crowd of people whom I imagined to be his friends, he was conversationally attentive to me. Still, I could feel the strain in every seam of my composure. I asked him about Bellow, who had died a few weeks before. He shrugged. He said he didn’t know him well. How was that possible, when the two of them had been stacked, one on top of the other, on so many nightstands of my youth?

When I could not bear the proximity for another minute, when I feared that I might grab the lapels of his light-colored suit jacket and shout, Don’t you know that you are my god? I gave Patrick the high sign with my eyebrows. We excused ourselves separately and made our way to an empty ballroom. Much of the art on the walls had been made by people who were, at that exact moment, eating lunch beneath the tent. Patrick and I held hands and tried not to scream.

“I am sitting next to John Updike!” I scream-whispered.

“You are sitting next to John Updike!” he silently screamed in reply.

After lunch we were separated, sent off in two directions by staff holding clipboards: Patrick went into the auditorium, while Updike and I took our seats side by side on the stage. Updike was going to present my award, which came with a certificate and a not insignificant check. Joan Didion was there, Gordon Parks, Chuck Close, Cindy Sherman, John Guare, all of us arranged on risers like a grade school class waiting to have its picture taken.

And then someone took our picture.

The ceremony that followed was epically long: honors bestowed, lifetime-achievement medals distributed, speeches made. The stage was hot, and as time passed the luncheon receded into distant memory. From where we sat, we could watch the members of the audience falling asleep in their theater seats: family, friends, editors, agents. Every time an award was given, Updike remarked on whether or not a kiss had accompanied the handing over of the certificate and check.

“Look,” he said, leaning sideways to whisper. “He kissed her.”

The two hundred and fifty members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters are writers, composers, visual artists, and architects. It is a fixed number. When a member dies, potential new members are nominated and voted on.* Twelve years after my visit, I received a letter informing me of my induction.

I stood in my kitchen and stared at the paper in my hand for a very long time. I was thinking of Updike. After my blunder with Tony Kushner, I had never allowed myself to wonder whether I might one day be elected. But someone had died and, in doing so, had made a place for me.

The Portrait Gallery is a large room in the Academy building that displays a photograph of everyone who has ever been a member. Black-and-white portraits in identical narrow frames hang floor to ceiling, side by side, without an inch of space in-between. The photos are arranged not in order of birth or death but of induction, as if that were the moment life began. I’d walked through the gallery briefly the first time I visited and had marveled at the assemblage, but when I went back in 2017, I had time to make a real study of the place. There at the beginning was Samuel Clemens, followed by Henry James and Edward MacDowell. They were among the Academy’s founding members in 1898. I walked slowly around the room, letting my gaze run up and down the walls. It was another afternoon in May. Soon we would be called to the luncheon and ceremony. Those things didn’t change. I hadn’t had a cigarette in twelve years and was well past missing them. People wandered in and out of the gallery, some of them talking, others standing there, taking it in—W.E.B. Du Bois and John Dos Passos and Winslow Homer and Langston Hughes and Randall Jarrell and Georgia O’Keeffe and Eudora Welty, Steinbeck and Stravinsky, Thornton Wilder and E. B. White—with this defining connection: they were dead.

But then I found I. M. Pei, inducted in 1963, the year I was born. He was still alive. After more dead people I found W. S. Merwin, inducted in 1972. Alive! Then dead, dead, dead, dead—until I found George Crumb, inducted in 1975. Alive. After that, a mix: alive and alive and dead and dead and dead and alive. It went like that, broken up, almost equal for a few short minutes, until finally the balance tipped and more and more people were alive, fewer were dead.

There was John Updike, the great man, whose work was now irretrievably out of fashion. Was there a college student anywhere who cut her teeth on those Rabbit novels now? Probably not. Could I have wished for a better influence in my early life, when I was still capable of being influenced? Never. There was Grace Paley, who had died in 2007. She had been my teacher in college. Her stories, full of practical activism, are perfect for these times, but who’s to say that anyone’s getting around to them? Two more of my teachers were on the wall—Allan Gurganus and Russell Banks—still very much alive. And then at last I came to the end of my review and found, already framed and hanging, the group of writers who would be inducted in a matter of hours: Kay Ryan, Edward Hirsch, Amy Hempel, Ursula K. Le Guin, Colum McCann, Junot Díaz, Henri Cole, Ann Patchett.

Me. My framed black-and-white photograph so clearly in the camp of the living. The picture I’d chosen to send was joyful because joyful was how I felt when they asked for one. I’m showing all my teeth and am completely out of step with every serious and circumspect photograph surrounding me. If you were to look at all those photos without knowing who any of us were, you would point to mine and say, “That one’s still alive.”

But the math in this room was inescapable—two hundred and fifty seats at the table and no one gets to stay. Over time, what is considered to be the center of the exhibition will shift, and my photograph will eventually be in the middle, closer to the group of those who are mostly dead, and then finally enveloped into the entirely dead. Dying was the essential contract, after all. The Portrait Gallery laid it out clearly: this is where I am, and this is where I’m going.

Somewhere a bell was ringing. We were being called outside to lunch. For a split second I wondered whether I hadn’t made a mistake by accepting the invitation, handing over my picture. Wasn’t that a laugh? It was a beautiful day, a day of celebration. We ate and then I took my place on the risers with the rest of my class.

Soon after getting home, I received a small white envelope in the mail with a small white card inside.

the officers of the american

academy of arts and letters

note with sorrow the death of

the novelist denis johnson,

of california, on wednesday,

may twenty-fourth, two thousand

seventeen, at the age of sixty-seven.

mr. johnson was elected in

two thousand fourteen.

The simple formality of the announcement moved me, and so I kept it. Another one came in June: A. R. Gurney was dead. In July, it was Sam Shepard.

I had a wooden box made to hold the cards. In the years since becoming a member, I’ve received forty-five of them. Ursula K. Le Guin died eight months after being inducted, her picture just a couple of frames over from mine. Philip Roth, who had been inducted in 1970, died the week after Tom Wolfe, who was inducted in 1999. The human impulse is to look for order, but there isn’t any. People come and go. When you try to find your place among all the living and dead, the numbers are unmanageable, but working within a fixed group—two hundred and fifty people, one building, a roomful of framed photographs—there’s no fooling yourself. Is this my time? Maybe and maybe not, but my time is coming, and it should. Someone out there is waiting for my place.

John Updike died of lung cancer in Danvers, Massachusetts, on January 27, 2009, three and a half years after I first stood on 155th Street and looked down the green lawn of Trinity Cemetery and out to the Hudson River, three and a half years after I sat beside him onstage. If I could stop time, it would be to read all of his books—the stories and novels and poetry and essays and criticism, the successful books and the failures, the ones I’d read before and the ones I’d never heard of. I wouldn’t care what anyone had to say about them. There would be so much of life left for me if that were all I asked for.

“Oh,” he had whispered after a particularly disappointing award presentation. “No kiss.”

When my name was called we walked down to the lectern together and he handed me the framed certificate and check, then kissed me on the cheek, the way a father kisses a daughter on her wedding day before stepping back.

That was the gift, not the award or the induction. It was the beautiful day, the view of the river, the long sloping lawn of the cemetery, the single cigarette, that kiss.