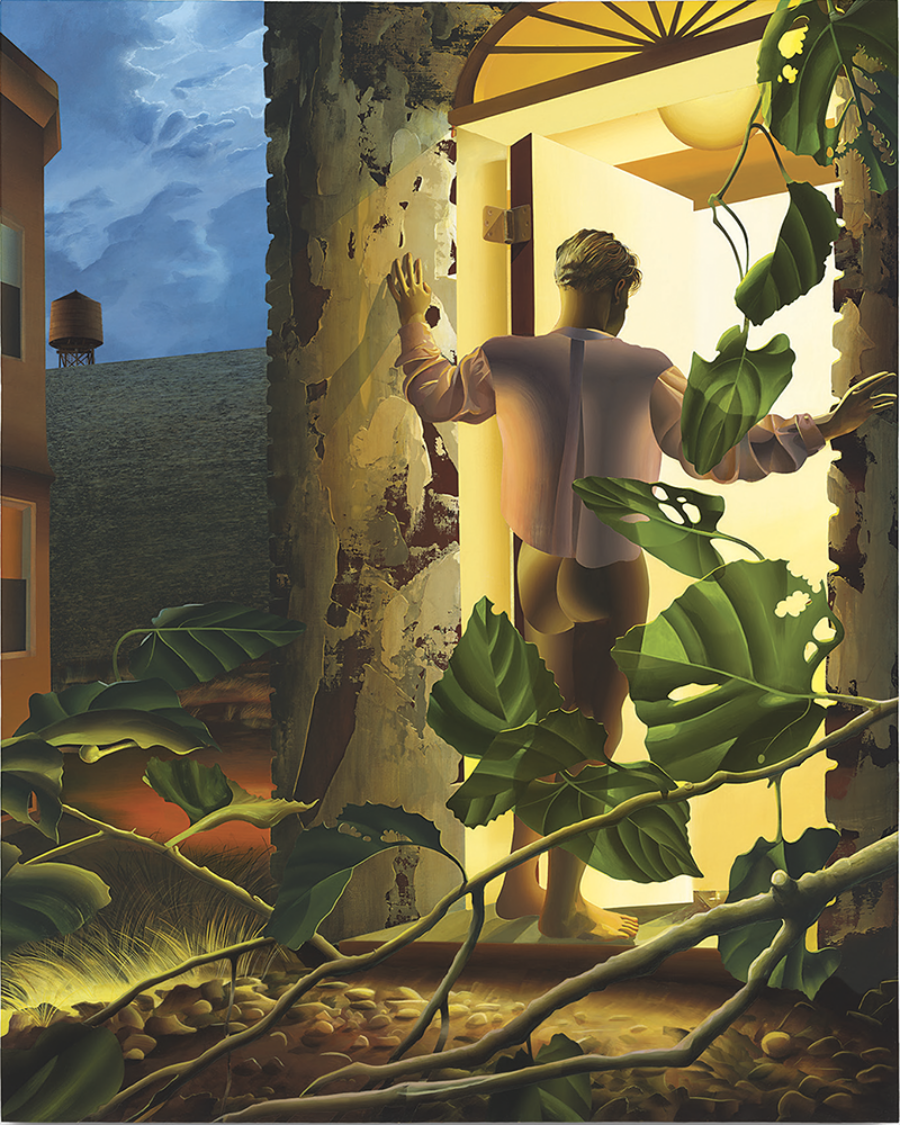

Homecoming, by Kyle Dunn. Courtesy the artist and P·P·O·W, New York City

Discussed in this essay:

The Letters of Thom Gunn, edited by Michael Nott, August Kleinzahler, and Clive Wilmer. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 800 pages. $45.

Thom Gunn wrote in an early notebook that “a good poem is simultaneously a tentative and risky cruising, a complete possession and orgasm, and a huge leather orgy. (Whether its subject is related to sex or not.)” His poems indulge in these pleasures (if not always “simultaneously”), and his correspondence also moves suggestively, to put it mildly, between different rhythms. In a letter to Douglas Chambers, one paragraph starts: “I had an extraordinary three-way with two guys I met in a bar one Saturday afternoon.” The next begins: “You ask difficult questions about scansion.” Another letter from the same year quickens the pace in a single sentence:

Now term is over, my garden is full of weeds, I keep meeting hedonistic young men on speed, I read book after book, and I have started on a song-cycle about Jeffrey Dahmer (the necrophiliac cannibal).

At seventy, Gunn concedes that “it’s an uneventful life, just sex, drugs, and excitement.” To John Ambrioso, one of his regular lovers at this time, he considers options for further excitement: a twisty dildo, a “monstrous” cock ring, “professional tit clamps, a real long ball-stretcher, industrial hoods (I made that up), police-gloves (heavy & gauntleted).”

Gunn had long enjoyed throwing down the gauntlet. Although the poems in his first collection, Fighting Terms (1954), come respectably dressed in spruce rhyme schemes and stanza forms, they don’t quite consider themselves fit for polite society. The opening lyric of the first edition, “Carnal Knowledge,” is spoken by a “forked creature” who may or may not be the poet, and who begins by admitting that “even in bed I pose.” Eavan Boland recalled her shock on encountering the work as a teenager. “Metrically, it makes a continuum with British poetry and looks to the past,” she observed. “But tonally it looks to a wide, improvised horizon, a future where irony and sexual dissidence would become a lens into a new poetic persona and a different configuration of modernism.” Gunn’s twin callings—the need to acknowledge his inheritance and the impulse to make it new—made his future difficult to predict. Over the course of his writing life he would often call on tradition (he edited selections of Fulke Greville and Ben Jonson), but he also kept dreaming up schemes to put past masters in mixed company. “I’d like to write a poem,” he confessed in 1973, “that was about leather, cocaine, gardening, Dante, the Grateful Dead, cats, and Caravaggio.”

Frequently at odds with trends in postwar poetry on both sides of the Atlantic, Gunn wasn’t drawn to the lyrical “I” that wore its heart on its sleeve (“I hate the whole idea of confessional poetry,” he once wrote, no doubt with poets like John Berryman and Sylvia Plath in mind). But then nor was he taken with the strands of New Criticism that imagined the “I” as a universal spokesperson; “It’s something I have great distaste for, the word universality,” he noted in an interview, “which we were always taught at school was something we should be finding in our reading.” Gunn’s “I” doesn’t seek to be “representative” (the word occurs just once in his work, in “Misanthropos,” to refer to a man who finds himself the last survivor of a nuclear holocaust). Instead, he wrote poems that seemed to emanate from a zone that was neither wholly private nor wholly public: “And now I stand each night outside the Mills / For girls, then shift them to the cinema / Or dance hall.” The antihero of “Lofty in the Palais de Danse” spends time out and about in communal spaces, but he’s also in the shadows, not quite visible, and he speaks in the poet’s characteristic accent, provocatively cool. “This seems to upset many reviewers, American especially, of Gunn’s poetry over the years,” August Kleinzahler noted. “They suggest that Gunn is a very cold chap, indeed, an emotional husk of a man.” These critics, he continued, seem to wonder why Gunn “isn’t coughing up his guts all over the page as is the custom in contemporary American poetry.”

Gunn had little time for the exposé, once casting a side-glance at talk of breakdowns, mental institutions, and suicide attempts in “the poetry of my juniors” before adding that “it is very poetic poetry.” But his droll caricature of this sort of thing, like the caricature of Gunn as merely “cold” or distant or lacking in feeling, misses a more intriguing state of affairs. “I wonder,” he wrote to a friend in 1971, “if the impulse to be nakedly honest is not in itself and unavoidably also an impulse to self-dramatize?” This might suggest that a truer study of the psyche and its place in the world could be conducted via indirection or obliquity. He had firsthand experience of suicide and breakdown: Gunn’s mother, whom he adored and who first encouraged him to write, killed herself when he was fifteen, leaving him and his younger brother to find the body. Gunn rarely spoke about this, and later described himself as “crippled” for about five years after her death. Then there was the anxiety over his sexuality (he didn’t come out publicly until the Seventies). Part of what makes his poetry so compelling is the sense it gives of a clandestine self, and its refusal to settle for the polarities of full disclosure and hermetic secrecy. He approved of Heraclitus’ description of the Delphic oracle, who “neither explains nor conceals but makes a sign.”

The Letters of Thom Gunn is the first book to present his private words for public consideration, and it makes for absorbing reading. The correspondence spans sixty-five years: the first letter written from London by a nine-year-old boy who bemoans Franco’s victory over the Republicans, and the last from San Francisco in 2004 in praise of the mayor’s decision to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples (“always nice to cock a snook at President Bush”). In between, we have Gunn’s thoughts on everything from pornography to poststructuralism, and his delight at being the soul of indiscretion. He would have been rightly scornful of anyone who took this material as a key to his oeuvre, but then without seeing the correspondence we wouldn’t be quite so aware of his desire to reveal himself. It turns out, for example, that during the Sixties and Seventies Gunn made repeated attempts to write an autobiography, which, he said, would “keep nothing back at all.” He eventually abandoned the project, but his work remained preoccupied by how the self might be both hidden and hazarded in writing, and by the question he ventures in an early letter: “One does wonder what one is, doesn’t one?”

Years later, he admitted to adopting “an attitude implying strength and charm” as a way of coping with the world,

but I never thought anybody believed that that was where I began and ended. It’s a strange feeling when one feels like crying out, “But I have conflicts and weakness too, don’t you see?”

“One feels,” not “I feel”—as though the cry of strangest, deepest feeling needs to back away from itself. Reading what Gunn didn’t choose to show to the public, and knowing what he did, it becomes clear how personal a writer he is, even when he’s seemingly at his most impersonal. The correspondence throws new light on his work by allowing us to see things other than his notorious coolness (in one letter he describes a friend as “coolly adult, unlike yours truly”). For Gunn, the personal is constituted by conflict, and by self-division as a response to outside pressures. In a climate in which people are often asked to pick sides—between confessional and representational poetry, say, or between tradition and innovation—Gunn’s love of what he called “living-between-opposites” is not so much an evasion as it is an extension of what it means to be a person: not least because, as he once noted, “we are not the same as our attachments.”

In several letters, Gunn apologizes for talking about himself at all, and often equates self-expression with self-pity. His childhood gave him reasonable grounds for that. His father was a drunk, angry man, brutal to Gunn’s mother. As the war approached in 1939, his parents divorced; and as it ended came his mother’s suicide. Gunn then completed his military service before going to Cambridge to read English in 1950. There he fell in love with Mike Kitay, whom he followed to the United States a few years later. When asked why he didn’t come out during this period, he replied,

I would never have got to America, for one thing. I would never have got a teaching job, for another thing. And I would probably not have had openly homosexual poems published in magazines or books at that time.

The sense of a person who is shrouded and scarred can be felt throughout his early work. Gunn said that “The Wound” (later placed at the beginning of his Collected Poems) was his first real poem, and, needless to say, the precise nature of the speaker-soldier’s injury is not spelled out. Several other lyrics both court and fear exposure, and convey a mood of personal as well as interpersonal estrangement. But Gunn’s travels helped to free something up, and one of the first poems he wrote after arriving in the United States in 1954, “On the Move,” is headed in a new direction—not quite sure of where it’s going, yet happy to be in transit. Enter “the Boys” on motorbikes: “In goggles, donned impersonality, / In gleaming jackets trophied with the dust.” Gunn bought himself a Harley-Davidson—“considered disreputable over here,” he explains in one letter (“The mere riding of one is, in a strange way, a sort of controlled irresponsibility”). Similarly, although his literary bikers travel from “known whereabouts,” they “use what they imperfectly control / To dare a future from the taken routes.” The same might be said of the poet’s shifting relations with his art and his life: he dares a future by taking liberties with taken “routes,” for the word must now carry an American pronunciation if it wants to forge a full rhyme.

By the time Selected Poems appeared in 1962, Gunn was a rising star—“clearly England’s most important export since Auden,” as one reviewer put it. The Selected sold more than eighty thousand copies in the United Kingdom, yet one of the most winning things about Gunn is his lack of interest in himself as a success story. He was looking to import, not export, and his voracious reading of American poets after settling in San Francisco—particularly William Carlos Williams—helped him loosen up his rhythms via a series of remarkable experiments in syllabics and free verse. He associated these experiments with a shift in outlook, a turning away from what he’d come to see as the self-regard of his early books (“Getting outside oneself was one of the things I learned from Williams”). If pushed to pick one place to start with Gunn, I’d choose the second half of My Sad Captains (1961), a beautiful baker’s dozen of poems which signals a major breakthrough. All these lyrics—at once stripped back and newly susceptible—unfold in the present tense, and some of them begin to sing of Gunn’s love affair with the modern metropolis, his adoration of what he called “the promiscuity of the streets.”

Many commentators have seen Gunn as a city poet, and certainly his need to get lost in the crowd feeds an anonymity that he sometimes craves. Yet, as he writes to Kitay in 1963, “it’s funny how egotistical my poetry is.” This may sound surprising given Gunn’s resistance to confessionalism and his emphasis on “getting outside oneself,” but it tells of his sustained feeling for how the attributes of a perceiver might be gleaned from the objects of his perception—as when, in one poem, he stares at a mintbush and wonders whether its existence as both a “full form” and as something “still-to-grow” could model his own potential. Indeed, Gunn’s eyes are always on stalks—or tendrils, or shoots, or leaves. He loved to write overlooking the garden (“plenty of vegetable activity to pause over”), and his correspondence is crammed with details about the state of the yard, details that send you back to his poems with a new eye for what might matter. Even while romancing the city, he seizes on tiny yet tenacious versions of pastoral: a glint of green erupts from a fissure in an aqueduct; weeds persist between paving stones or in potholes. The pick of the bunch is “street-handsome” nasturtium, born in a waste lot, laboring up toward the light, and now running out of sight through a knothole: “A prodigal has risen, / Self-spending, never spent.”

Gunn became the prodigal son who never returned, and many English critics lined up to castigate him for running to seed—and to free verse—in America. But the poet continued his self-spending in both metered and looser forms. Crucially, he remained fascinated by how style could be played off against content. In 1968, he admits to Tony Tanner that if his subject matter is impulsive, “it only becomes something more when the metrical form examines it,” and he warms to this cross-pollination in other art forms too (Pulp Fiction, he says, “is a bit as if Henry James were to write a treatment of Titus Andronicus”). On reading this, I was reminded of Stephen Spender’s evaluation of Gunn’s work in the early Seventies: “It is as though A. E. Housman were dealing with the subject matter of Howl, or Tennyson were on the side of the Lotus Eaters.”

By this point Gunn was no longer simply gazing at plants; he was ingesting them. Having given up a tenured position at Berkeley, where he continued to teach part-time until retirement, he signed up for the Summer of Love. For those in search of the glorious, gory details of Gunn’s copious drug-taking—from grass and mushrooms to crystal meth—the letters don’t disappoint. (“A mild psychedelic, and a very wild aphrodisiac,” he reports of MDA in 1971. “I have on no other occasion had sex for SIX HOURS!”) Yet his pleasure-seeking was often accompanied by something more sober-minded. The LSD poems of Moly (1971) are written in tightly controlled forms; moly, after all, was the herb Odysseus ate to protect himself against Circe, who turned men into pigs. “Some might see it as the thorazine to be used for an acid freak-out,” Gunn wrote to a friend, “but let it be, that ambiguity.” The ambiguity bears on his interest not so much in the effects of LSD as its aftereffects. “People who go on about their trips are very boring,” he admitted. Yet now that the trip was over, “I still feel beautifully clean-brained from it.”

Beautifully clean-brained is an excellent description of Moly. Gunn always said it was his favorite volume, and it charts the self’s patterns of merging and emergence with great power. For while the poet seeks to loosen the bonds of personality via various kinds of shape-shifting (or, more trippily, by belonging to the universe), he also wants to make the journey back to singularity. The first poem in the collection, for example, “Rites of Passage,” is spoken by a figure who appears to be turning into an animal (“Horns bud bright in my hair”) or being absorbed into nature (“My blood, it is like light”). Yet alongside these dissolutions of identity one catches hints of Gunn’s tortured personal history: “I stamp upon the earth / A message to my mother.” We learn from the letters that Gunn had considered titling the book The Metamorphoses, and everything in it—animal, vegetable, and mineral—appears to have more than one life to live:

The cracked enamel of a chicken bowl

Gleams like another moon; each clump of reeds

Is split with darkness and yet bristles whole.

The field survives, but with a difference.

The accuracy and mystery of this passage—the sense it gives of a deeply watchful self, in both senses of the word—is characteristic of Gunn. You feel that he’s looked at each clump of reeds, just to double-check, even if he can’t (or won’t) spell out the difference in that field. “By a chicken bowl,” he explained in a poker-faced note, “I simply meant a bowl from which chickens on a farm eat or drink.”

As he was finishing Moly, Gunn wrote to a friend about some graffiti he’d encountered in a gay bar: “We are the people our parents warned us against.” How, then, to tell the parents? As far back as 1961, he’d written privately of his desire to write openly queer poems. By the end of the Sixties, Gunn’s relationship with Kitay had expanded to include other men; their house had become something of a gay commune, and Gunn was amused when someone noted that the setup sounded like a French art-house movie. By the end of the Seventies, he’d marched in his first gay pride parade, come out in print, and taken a stand against homophobic slurs (“I decided, fuck it, if they are going to be anti-gay, they don’t get this gay’s contributions”). Yet as the letters make clear, he didn’t particularly like reading or being included in anthologies of gay writing, and he didn’t want his work to be understood solely in reference to his sexuality. He took issue with those who parroted the phrase “the homosexual life style” (“As if there were many ‘life styles’ for heterosexuals and only one for us!”) and he objected to how the media rehearsed

the dreary mythology of s and m . . . all the rigidities of role and routine which I find repulsive . . . There are as many different homosexualities inside as there are outside the leather bar.

Gunn once remarked that he read to encounter both “similarity and dissimilarity, likeness and difference.” What he was looking for in poetry was what he was looking for from life: “a frisson of unrelatedness.”

He’d always explored the friction between a dissident existentialism and an urge toward some imagined solidarity. In later years, his blend of reticence and responsiveness, as well as his awareness of the body as both an inscrutable site of demand and a point of shared contact, informed some of the finest poems he ever wrote: the AIDS elegies in The Man with Night Sweats. Gunn lost most of his friends to the disease, and his letters record the trauma of the experience, which led him to a reckoning not just with how much of himself he wished to reveal in poetry, but with how far his identity was bound up with modes of identification. “The gay community,” he admitted in 1995, was “a phrase I always thought was bullshit, until the thing was vanishing.” This ambivalence speaks to the difficulty of knowing exactly where to put yourself at such moments, and of how to put yourself. “I can both imagine and not imagine how you feel about losing Cliff,” Gunn wrote to a friend who’d lost his partner. His poems register the insufficiency not just of words, but of feelings.

He composed the first of the elegies, and his longest single poem, “Lament,” for Allan Noseworthy, who died in 1984. Ten years earlier, Noseworthy had been the “gorgeous big” doorman at Ty’s, a leather bar in New York, and he and Gunn had begun a sexual relationship that then developed into a close friendship. Noseworthy later founded an AIDS hospice program, and Gunn cared for him during his last weeks. “Lament,” in which the poet speaks to Noseworthy, is itself a letter of sorts—one that knows it won’t be heard but is still unable to abandon the second-person address. This strange quality in Gunn’s poetry is something that his letters help us see. It often seems in his correspondence that he’s talking to someone else as a way of talking to himself—or, rather, that he’s alone with his thoughts even as he seeks the consummation of thought through call-and-response. The poem draws toward a close as Gunn tells Noseworthy about the aftermath of his death:

Outdoors next day, I was dizzy from a sense

Of being ejected with some violence

From vigil in a white and distant spot

Where I was numb, into this garden plot

Too warm, too close, and not enough like pain.

I was delivered into time again

—The variations that I live among

Where your long body too used to belong

And where the still bush is minutely active.

Like much of Gunn’s best writing, this is not simply coping with feeling—still less being consoled by it—but trying to reach it, to grasp it. The phrase “and not enough like pain” speaks of nature’s indifference, but it also outlines Gunn’s own emotion: shocked, detached, and yet starting to detach a little from his own detachment. For when something is not enough like pain, it is not necessarily unpainful; it’s just that more pain might at least bring a desired clarity, might offer itself as the evolution of an ache. As the poet slips from the past to the present tense, he finds that the self is forced to take stock of time in the very act of writing, in which loss is always now, not then.

After Noseworthy’s death, Gunn visited his apartment:

he had kept every letter, it looked like, that had ever been written to him, so I located an enormous bundle by myself and dropped them in a dustbin outside. As a friend said who had to clear out Sylvia Plath’s flat after her suicide: “The dead leave everything behind.” Don’t they just.

In Gunn’s life, the dead person who left everything behind was his mother. She first appears in Gunn’s poetry in the AIDS elegies, and his last collection, Boss Cupid, features two poems about her. But she’d always been there. As the letters show, she came back in Gunn’s dreams throughout his life (“a very strange dream where I found my mother dead. I thought, callously, ‘Oh no, not again. I think I’ll let somebody else find her body this time.’ Which I did!”); as well as with the seasons: “I am always depressed in January,” he wrote on New Year’s Day in 1994, “and it was only a few months ago I figured it out. My mother killed herself on Dec 29, 1944, and I think I set my moods an annual pattern from that.”

Maybe she also comes back when nobody’s looking. Kitay noted that “if Thom was sentimental about anything, it was our cats; particularly the dead ones.” They often appear in nonsentimental guises in his poetry; kittens turn into furies in “Jack Straw’s Castle,” and in a late lyric he says that cats do not give even the semblance of love because they are “beyond pity.” They pop up in the letters too. Speaking of the abrupt disappearance and return of his close friend Don Doody, Gunn writes: “I expect he will one day commit suicide. Which I don’t, need I say, mean as a joke . . . Little Mr Cat and little Miss Tomato send their weeny, furry kisses.” Somewhere behind all this, I think, is a detail from a harrowing diary entry that Gunn made on the day he found his mother’s body: “The cat was nestling and purring with a pleased look and half-shut eyes, in the dressing gown’s folds between her legs.”

If Gunn managed to survive the trauma of his childhood by dissociating, then his poems became a way of reintroducing himself to himself—partly through how he restaged his relationship with others. A metaphor he once used to describe a poem he admired is revealing—“a cat’s-cradle of allegiances, criss-crossed with the pull between public and private speech”—and the pull can be felt in a tough-tender poem composed more than thirty years after his mother’s death. In “The Cherry Tree,” he imagines a mother tree wearing her blossoms like “a coat of babies.” The prompt for this image, Gunn noted in a late interview, was his pet cat; after she had kittens he was struck by how, although she was very attached to them at first, she became indifferent to them as they were “getting out on their own.” The cherry tree initially works to feed her offspring, but comes to care less and less as birds and men pick at the blossoms. “That’s why she made them,” after all, “to lose them into the world, she / returns to herself, / she rests.”