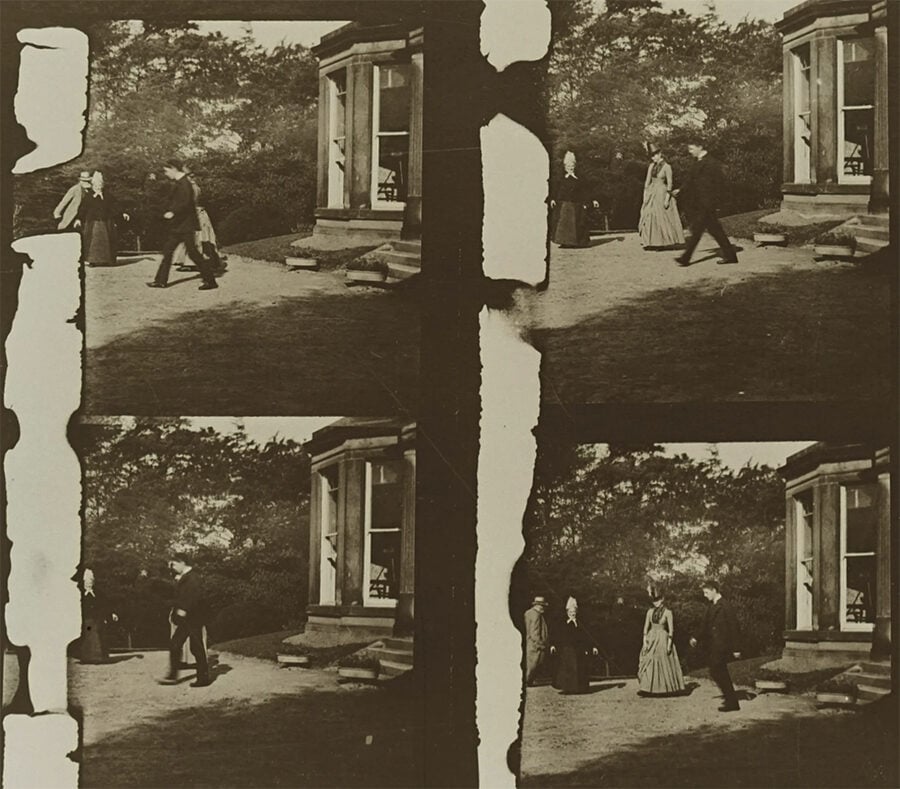

Stills from Roundhay Garden Scene, October 1888, by Louis Le Prince © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, London. Courtesy Science Museum Group

Discussed in this essay:

The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies, by Paul Fischer. Simon and Schuster. 416 pages. $28.99.

On the morning of October 14, 1888, Louis Le Prince set up a heavy wooden box in the garden of his father-in-law’s small manor house on the outskirts of Leeds. The box was made of Honduran mahogany, burnished to a soft sheen, and stood on splayed applewood legs with iron fixtures. Le Prince turned the brass crank and began filming. The surviving footage is so mundane that it takes…