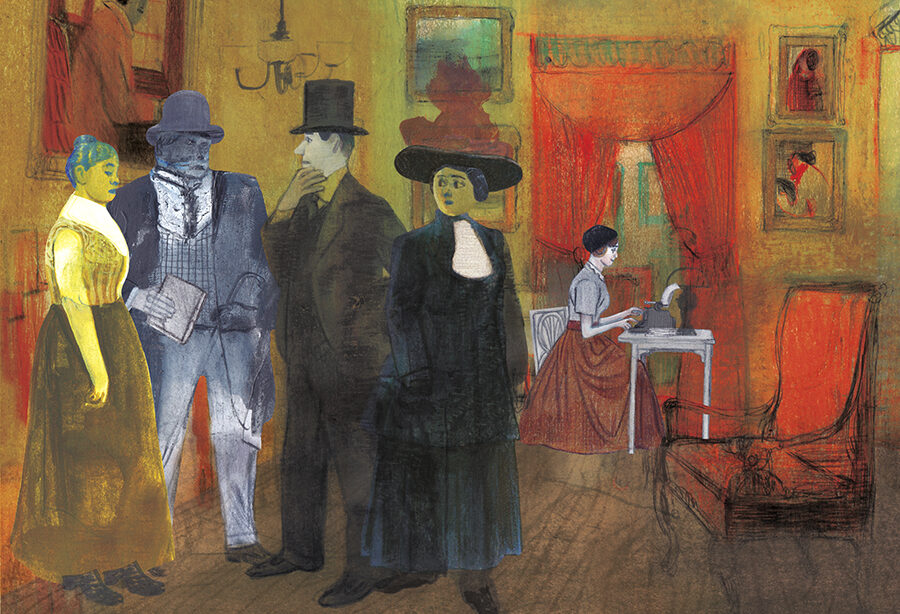

Illustration by Jorge González

Discussed in this essay:

Trust, by Hernan Diaz. Riverhead. 416 pages. $28.

In the Distance, by Hernan Diaz. Coffee House Press. 240 Pages. $16.95.

Every nation has delusions about itself that it holds dear, delusions that take the form of stories. America’s own foundational stories—its heroes and archetypes, its go-to plots—are perhaps better read not as a way of understanding ourselves, but as permission to avoid understanding ourselves. Some of our most internalized parables of American motive, American character, are soothing misdirections. What is a western, after all, but a kind of hermeneutic care package…