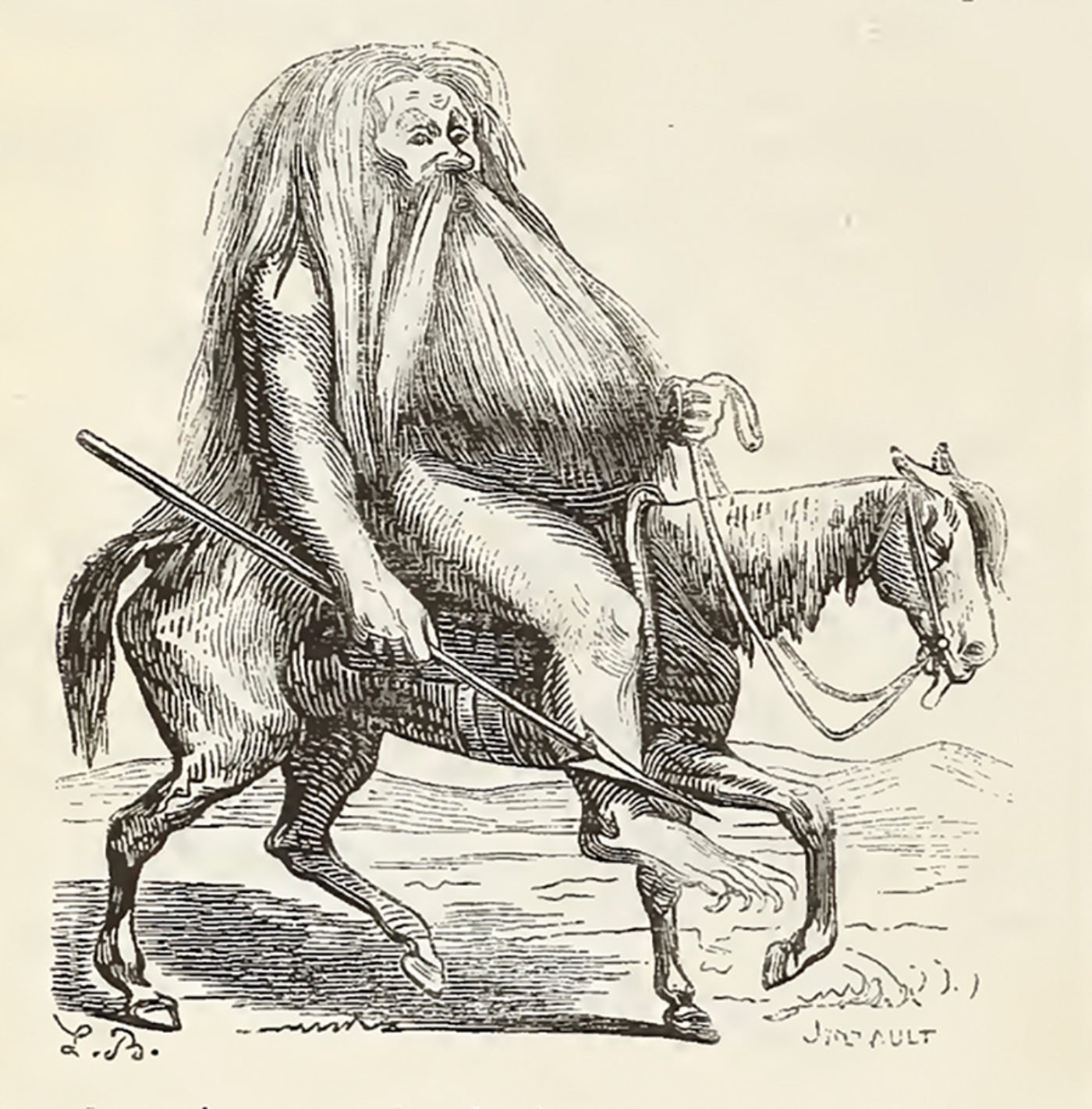

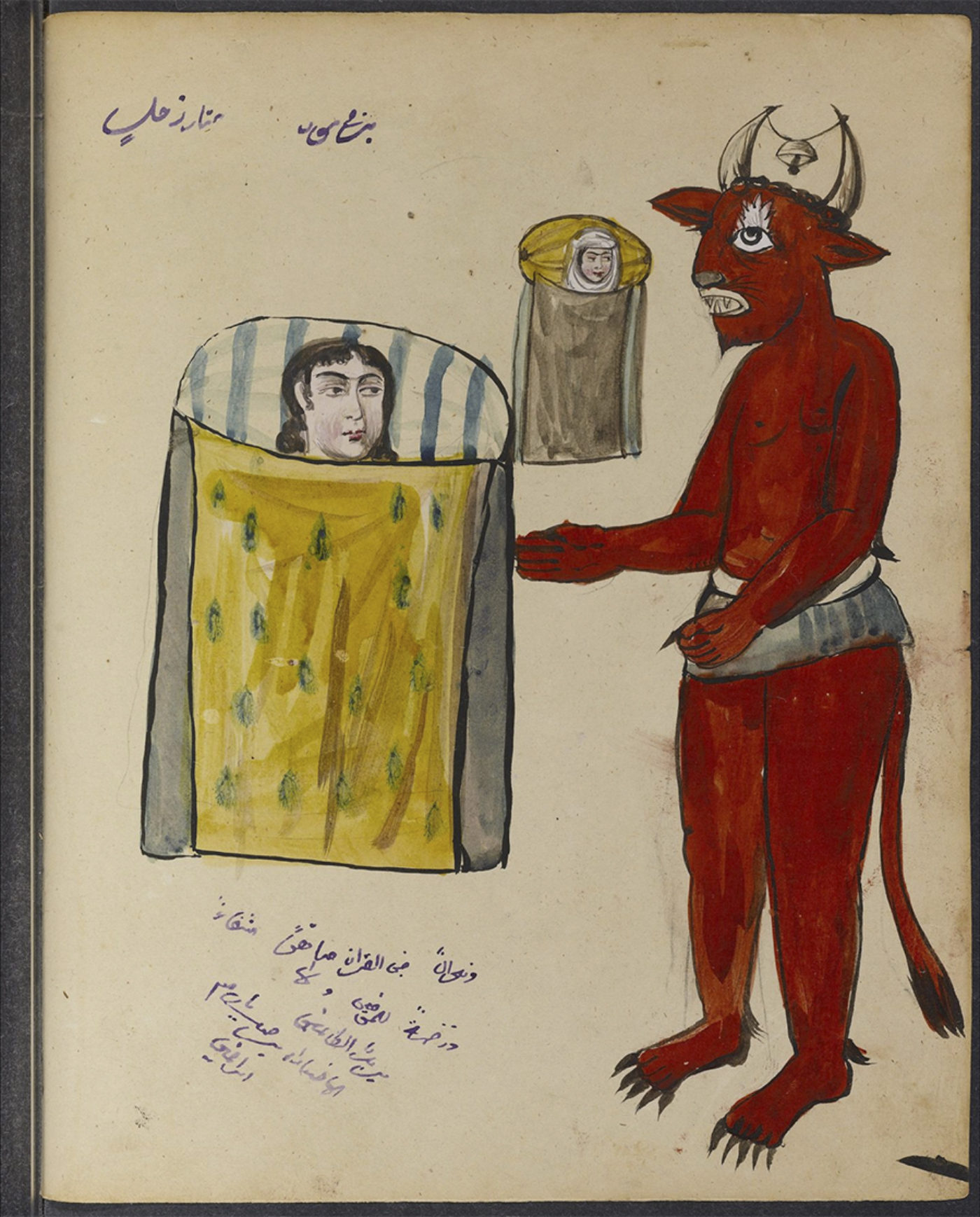

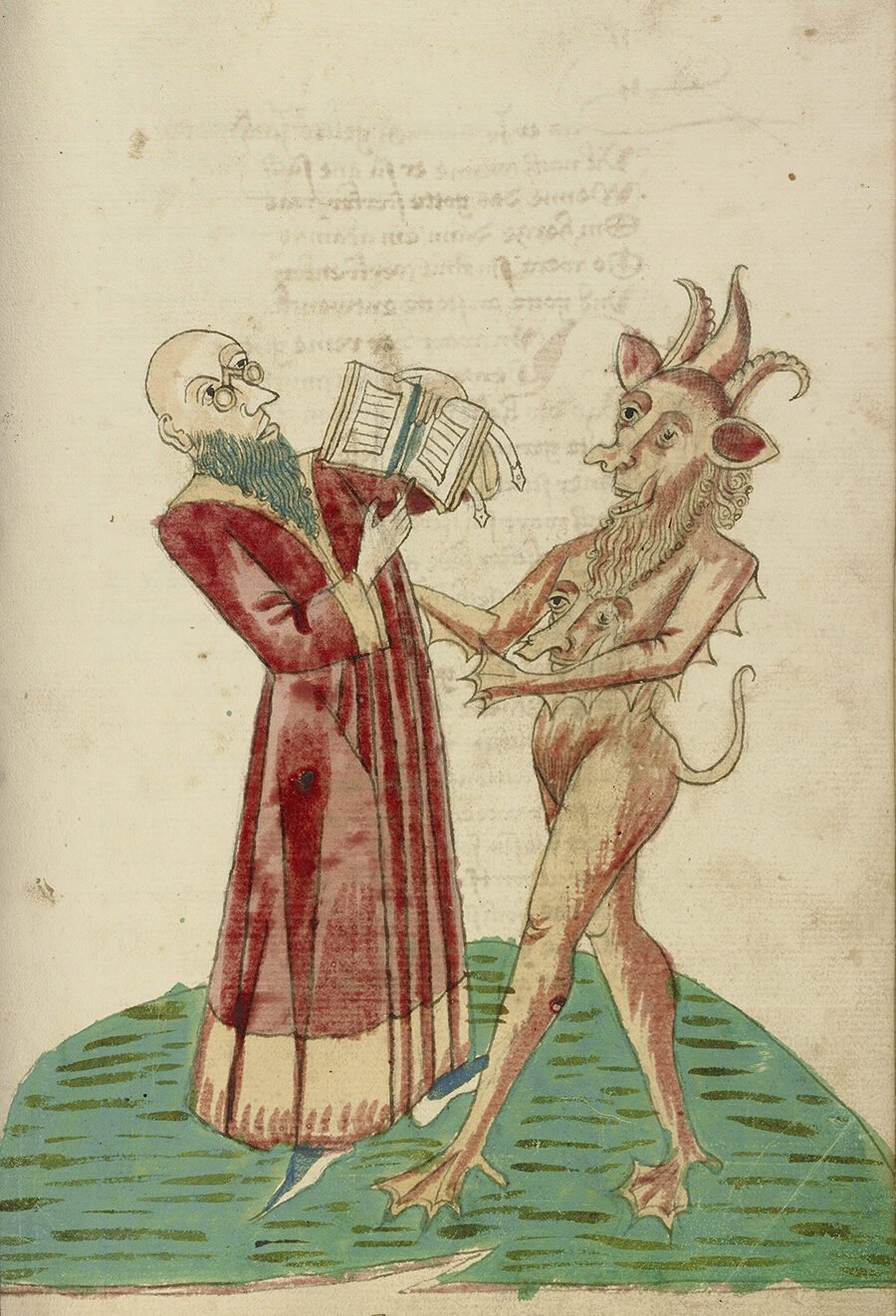

Theodas with the book of magic and the devil, from Barlaam und Josaphat, 1469. Courtesy the Getty Center

The wizard’s blog opened thusly: “I, the sole legitimate heir to the ancient magical traditions of King Solomon the Wise, propose to demonstrate his powerful art in its true and proper form so that it will not pass from history unknown.” In the starched prose style of a naturalist, the wizard detailed nearly two decades of spirit conjurations and regular interactions with ancient evil entities such as Paimon and Belial. He alone could do this, he swore. He alone could summon these demons, and bind them. He alone could prove their existence.

The man was not shy about signing his real name: John R. King IV. In fact, he was something of a celebrity among the small yet expanding subculture of dead-serious magicians. On Facebook and obscure message boards, these men (and they’re almost all men) quibble over demonology, teach one another Latin and Hebrew, and share high-resolution scans of archaic spell books. They pool notes and trade conjuration hacks like programmers working with open-source code.

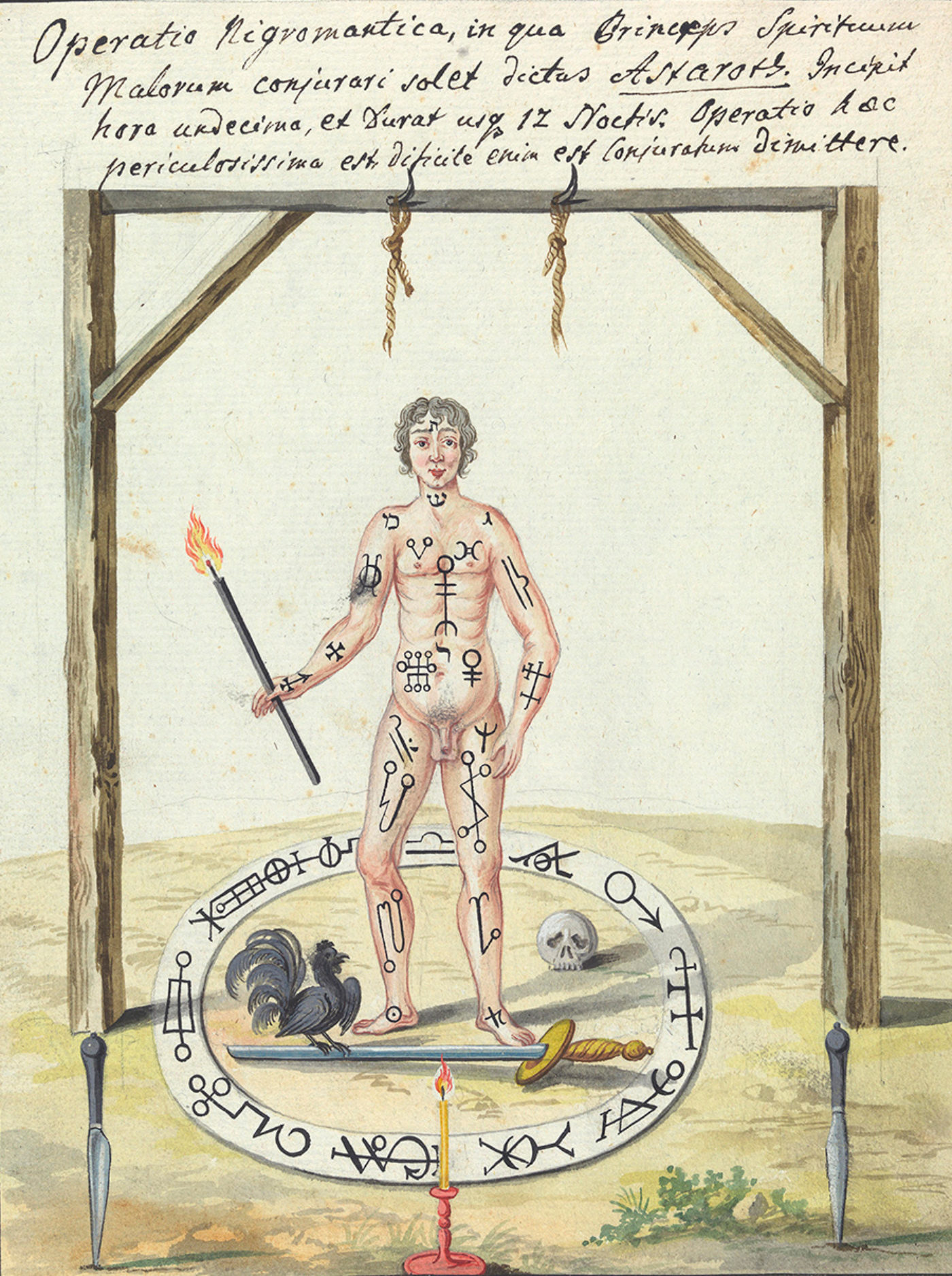

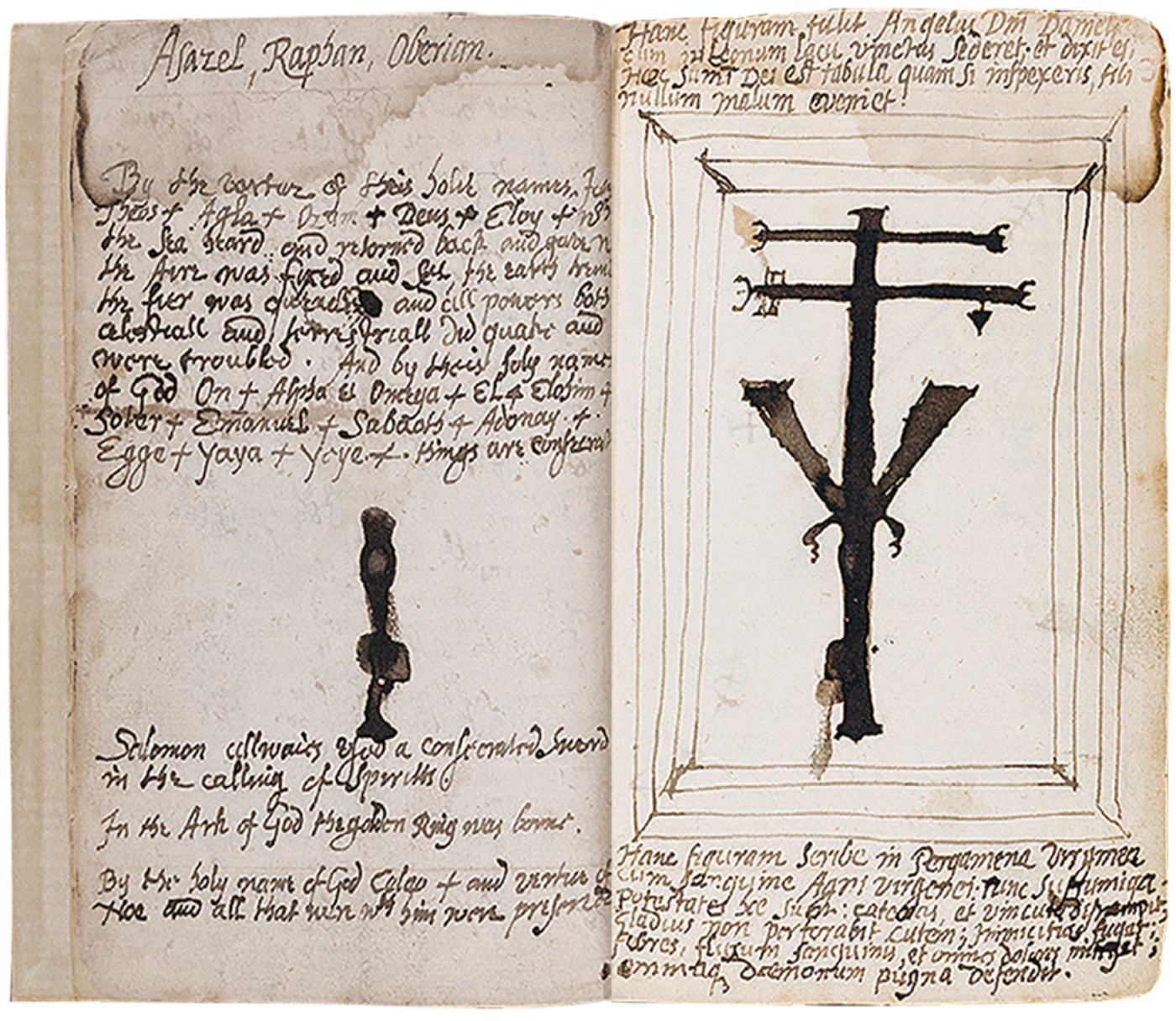

King uses a spell book—or grimoire—known as the Lesser Key of Solomon, which is believed to have been translated into English in the mid-seventeenth century, although it likely contains texts that are much older. King boasted that he followed its instructions “to the letter, neither adding nor subtracting from the ritual.” “In my opinion,” he wrote, “a truly scientific examination of the occult—this art in particular—cannot occur if the laboratory conditions and procedures are not met and thoroughly tested.”

Aside from this fastidiousness, King attributed his success as a mage to his considerable goldsmithing skills. For the rituals of the Lesser Key are centered on talismans made from precious metals, and these talismans require quite a bit of smithing, stone setting, engraving, and forging. The many steps are onerous, and must be undertaken by a magician whose mind is settled and fixed upon his work, on the day and at the hour of the planet involved, in a fortunate place, and during fair weather.

Blood sacrifice this is not. Ceremonial magic is more akin to a legal proceeding than a Black Mass. There are rules to which demons are bound. King claimed to act as a representative of this order, subpoenaing and deposing whom he pleased like a district attorney. The encounters were formalized in parchment contracts complete with looping script written in india ink. “Behold your confusion if you refuse to be obedient!” read one of King’s standard forms.

Therefore make rational answers and be obedient, in the Name of the Lord. Welcome, ______, most noble ______! . . . By that same power by which I called thee forth, I bind thee to remain here so long as I have occasion for thy presence, not to depart without my license until thou hast dutifully fulfilled my will.

When I first came across King’s blog late one summer night in 2019, I felt stunned and exhilarated, as though I’d been electrified by a bolt from the blue. King’s writing shocked me out of a despondency that was not too extraordinary, I don’t think. At the time, I was finding myself bereft of a sense of purpose, as well as a horizon to look forward to. I was despairing over the death of civility, the collapse of public trust, and the obliteration of consensus reality. Existence had been whittled down to the dumb play of atoms and a tribalistic will to power. It was as if malevolent entities had been loosed upon the world, to make sure the center did not hold.

But what if? I wondered. What if you could actually show the world a demon? Not a symbol or conceit, but a living, malign intelligence that transcends the material plane and reacquaints us with our first language: fear. Wouldn’t that change everything? Wouldn’t it free us to know it’s all true?

Reading King, I felt myself vacillate between terror and wonder like a compass needle brought near a magnet. Here was a man who had punctured the airless dome of modern existence, and, what’s more, was really goddamned cocksure about it. “Again,” King wrote, “I invite anyone who doubts me personally to come to me . . . I will be glad to resolve any uncertainties you may have about my life and work.”

So that’s what I did.

King sent me things. Copies of his paintings, for instance. In one, the tentacles of a kraken envelop a Viking longship. In another, a T. rex lunges at the neck of a stegosaur. He worked primarily in oil paints. I was unsure whether this meant he had hobbies, or was Hannibal Lecter–nuts.

I got him to agree to video-chat with me. Onscreen, King was short and slight, a forty-something man built like a gray alien. His head seemed an order of magnitude larger than his body, and his brown hair was both thinning and receding. He counterbalanced this with a thick, full mustache.

King spoke deliberately, with a wisp of a Tennessee accent. He was extremely sensitive to the precision of words, and I could tell this sensitivity brought him less joy than sorrow. Even in casual conversation, King winced at my crudity and malapropisms as though they were shirtsleeve affronts. He, on the other hand, had received the gift of rhetoric from Furcas, a Knight of Hell entreated early in his wizarding career.

I explained why I’d reached out. When it comes to the supernatural, I said, I am as the dorm-room poster: i want to believe. Skinwalkers, Jungian synchronicities, hollow-earth theories, Vallée-ian UFO speculation. With hokum such as this, my credulity can be counted on.

A great essay, like the one you’re reading now, showcases an author’s singular voice even as it strives to reveal universal truths. Harper’s Magazine needs your support to continue publishing work that respects and stimulates readers and writers alike.

A great essay, like the one you’re reading now, showcases an author’s singular voice even as it strives to reveal universal truths. Harper’s Magazine needs your support to continue publishing work that respects and stimulates readers and writers alike.

But my interest, I clarified, while probably morbid, is not merely personal. It stems from a keenly felt, soul-sucking disillusionment. By accident of birth I am a modern, which means I will never know a charmed world. A world of consecrated hosts and faerie-haunted forests, where the line between individual agency and impersonal force is blurred at best. Gone is the idea of a porous human self, vulnerable to immaterial forces beyond his control. Significance has retreated from the outer world into our respective skulls, where, over time, it has stiffened, bloated, and finally decomposed into nothing, into dust.

This decay of faith—in institutions, in other people—is practically audible to me. I exist within a purely immanent culture in which the value of human life has been reduced to the parameters of the marketplace, where little is sacred and even less is profane. And I cannot take this shit much longer, I said.

“At this point, does one not wish for demons?” I asked King.

In fact, he told me, I already had proof of their existence.

“This is something that I requested,” King said, explaining how he had asked the spirits to bring him a middleman who could connect him to the masses. “Not too long ago I said, ‘I would like someone to come forward to get this kind of project going.’ ”

“What you are saying,” I enunciated carefully, “is that I have been touched by a demon?”

“I normally wouldn’t tell people that,” King said. “But, yeah.”

As King breezed past this revelation, my stomach plummeted. My scrutiny turned inward. I reconsidered some weird events of the past few weeks: cockroaches pouring out of a broken light fixture, a ringing in my ears that may or may not have been related to a gas leak, the smell of fresh flowers wafting suddenly over my (unwashed) bedclothes. I tried to make out a pattern, thought I might be seeing fog on the mirror. Then I waved this away as ex post facto wish fulfillment as applied to the vicissitudes of Section 8 housing.

My need to be dispossessed of myself was causing me to imagine things. This would not do. Either King would show me a demon, or I’d force the one he sent to reveal itself.

San Francisco de Borja Exorcizing an Evil Spirit from an Impenitent Dying Man, by Francisco Goya © Album/Alamy

In the weeks that followed, King and I established a routine of video-chatting deep into most Monday nights. He filled me in on his background: Born in Nashville, raised in Memphis, mother was a microbiologist, father was an architectural draftsman. Though not Catholic he attended a Catholic school, and in the fifth grade Brother Larry Schellman taught him about shamans, swamis, and thaumaturges, as well as the Catholic Church’s position on them—namely, that their powers are real but demonically granted. This piqued King’s interest. “I thought, Hey, great, I can get the same powers without needing to be a good person.”

At fifteen he apprenticed with a Native American diviner named Harlen, and at seventeen it was on to Fern the witch. They instructed King in intuitive forms of folk magic. After that he studied English literature at the University of Tennessee, then relocated to Crescent City, California, where he bartered an almond-size emerald for lessons in the jeweler’s arts from Eric Smith of Eric’s Fine Jewelry. In his free time, King immersed himself in historical demonology, reading “nearly everything of import on this subject that has been put down in English.”

His studies paid off; the spirits found him a (first) wife and a job with the Bernard K. Passman Gallery at the Venetian Resort in Las Vegas. For the better part of a decade he earned $19.50 an hour designing black coral jewelry for tourists. He then became a bulk purchaser of gold; opened his own jewelry store; closed that store and opened another on an island in the Puget Sound; got divorced; lost the store; and now, twenty-two years later, works at a strip-mall jeweler’s in a Seattle exurb. “The graveyard of jewelry careers,” he called it. “At least I never have to do a ‘get a job’ spell.”

As captivating as I found King’s vocational odyssey, I was much more curious about his adventures in the demonic—particularly his encounters with their physical manifestations. For as he had written:

It should be noted that the spirits appear visibly and speak audibly, as they are commanded to do. . . . I would also submit that I am not prone to visions and hallucinations of any sort, nor to fantasies and deceptions; so it is upon my critics to suggest a means by which a rather simple ceremony as this can render a sane person temporarily and predictably psychotic.

These aren’t your shrieking private wants, right? I asked. The demons really do present themselves as clothed consciousnesses?

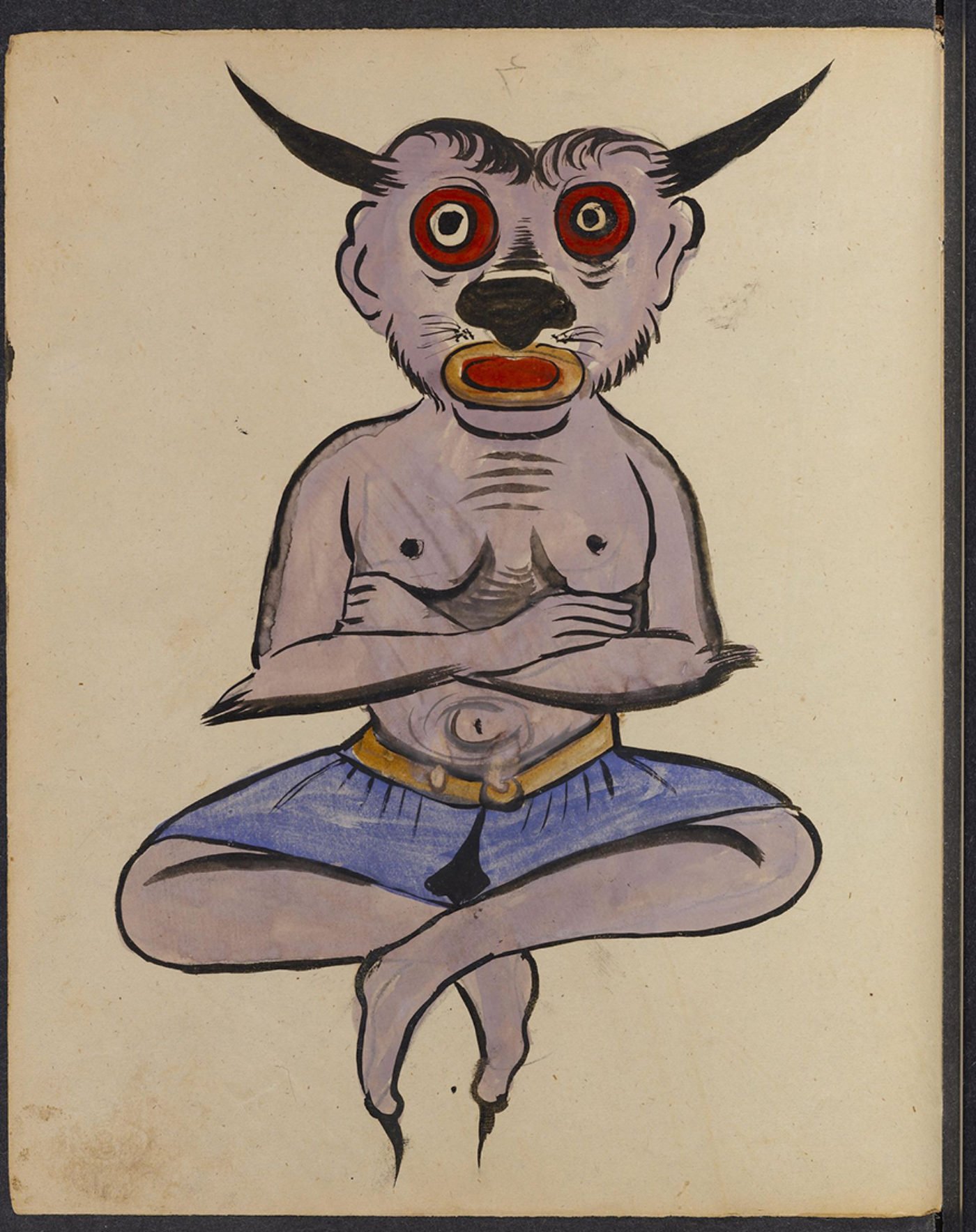

The spirits appear instantaneously, King told me. There is no gradual rise from the floor or coalescence out of vapor. “It is basic and efficient, and more unsettling as a result of that,” he said. King pointed me to his conjuration of Haures, Duke of Hell and commander of thirty-six legions, known better as the Egyptian deity Horus. This spirit appeared first as an enormous, shaggy, hunchbacked leopard. “Supplicants convene for my adoration. Do not delay me beyond necessity!” it spoke. Then it stood to reveal “a man with a face blackened as if by flame, and eyeless.”

“Who is God?” King asked the demon.

“God is that which can destroy with impunity, demanding worship from whatever it threatens,” Haures replied.

“I found the answer simplistic and unsatisfying,” King told me. Then he clarified: “That a demon would have something worth hearing, and reliable, to say about God is a strange proposition. The spirits cannot be given implicit trust in the least thing.”

Weeks turned into months. Slowly it dawned on me that I was performing the role of Boswell for a man who might be: a) a put-on maestro or arcane troll; b) a fiction writer slash performance artist; or c) a lunatic. But by his own admission King had tagged me with a familiar spirit. Whether or not he was telling the truth was irrelevant at this point. I could feel something squatting on my soul. I needed to see what it was.

I pressed King to let me watch him conjure. Show me a scream full of hooves, I said, or a smile spreading across a pool of blackness. He demurred. He had to ascertain what kind of person I was offline before that could happen. So we made plans to meet at the Okanogan Family Faire, a festival where especially dirty hippies encamp alongside militiaman types in a valley on the far side of the Cascades. For several days, they sing and dance and barter goods and services—mostly drugs. King would be offering tarot readings, but for me, he said, he might perform services that would disclose how demons affect everyday lives, my own included. I booked my flight and dusted off my camping gear.

In preparation, I dove into the books of magical lore that King had recommended. This was no small task, as mankind’s desire for communication with the deeper, intangible levels of reality is older than history itself. As long as there has been speech, there has been magic. It has survived the coming and going of empires and scientific revolutions; it has outlasted the brutal proscription of ecclesiastical authorities and the indifference of the recent past. Magic appears to be irrepressible as well as ineradicable, which is doubly interesting when you consider that its promises are supposed to never come true.

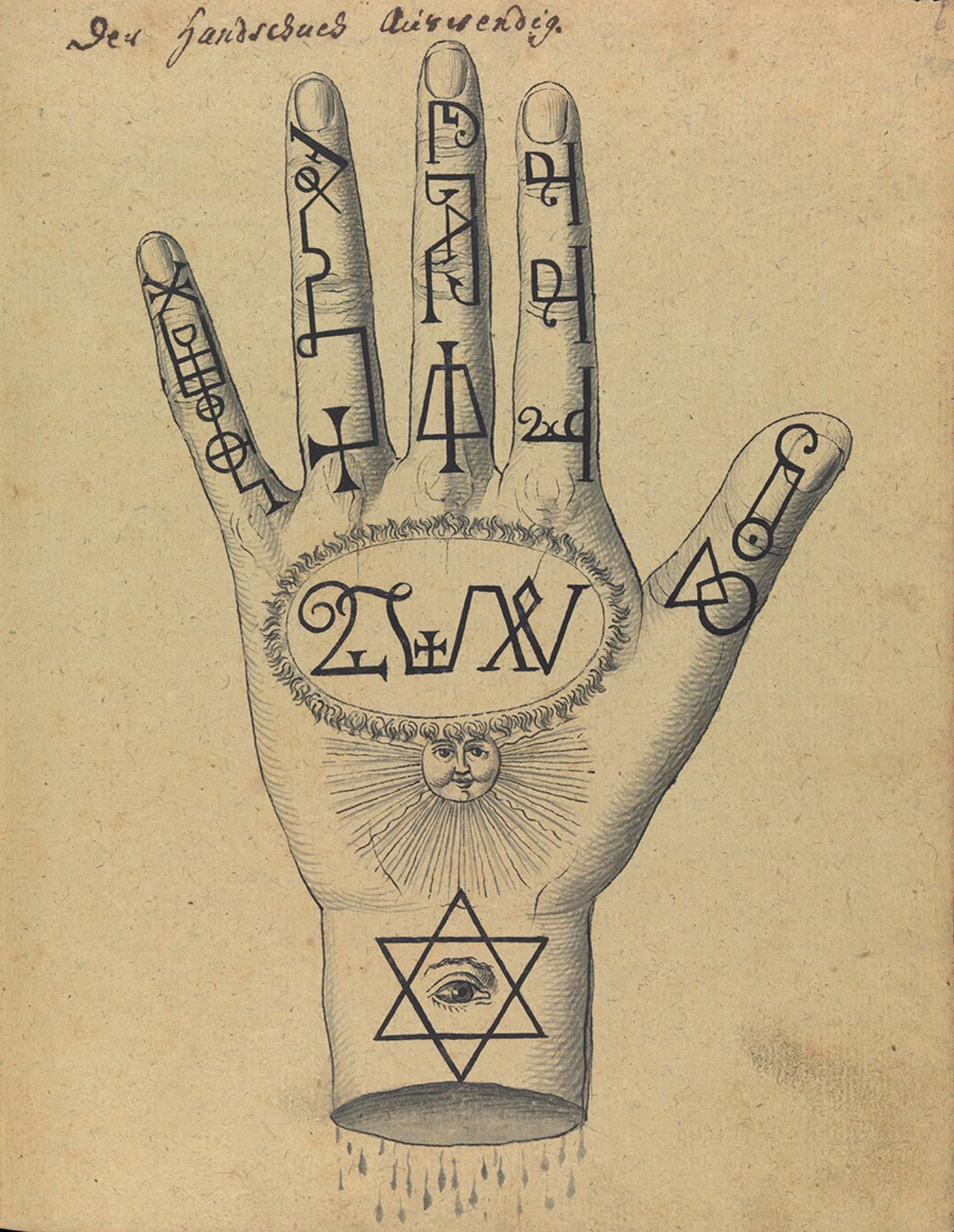

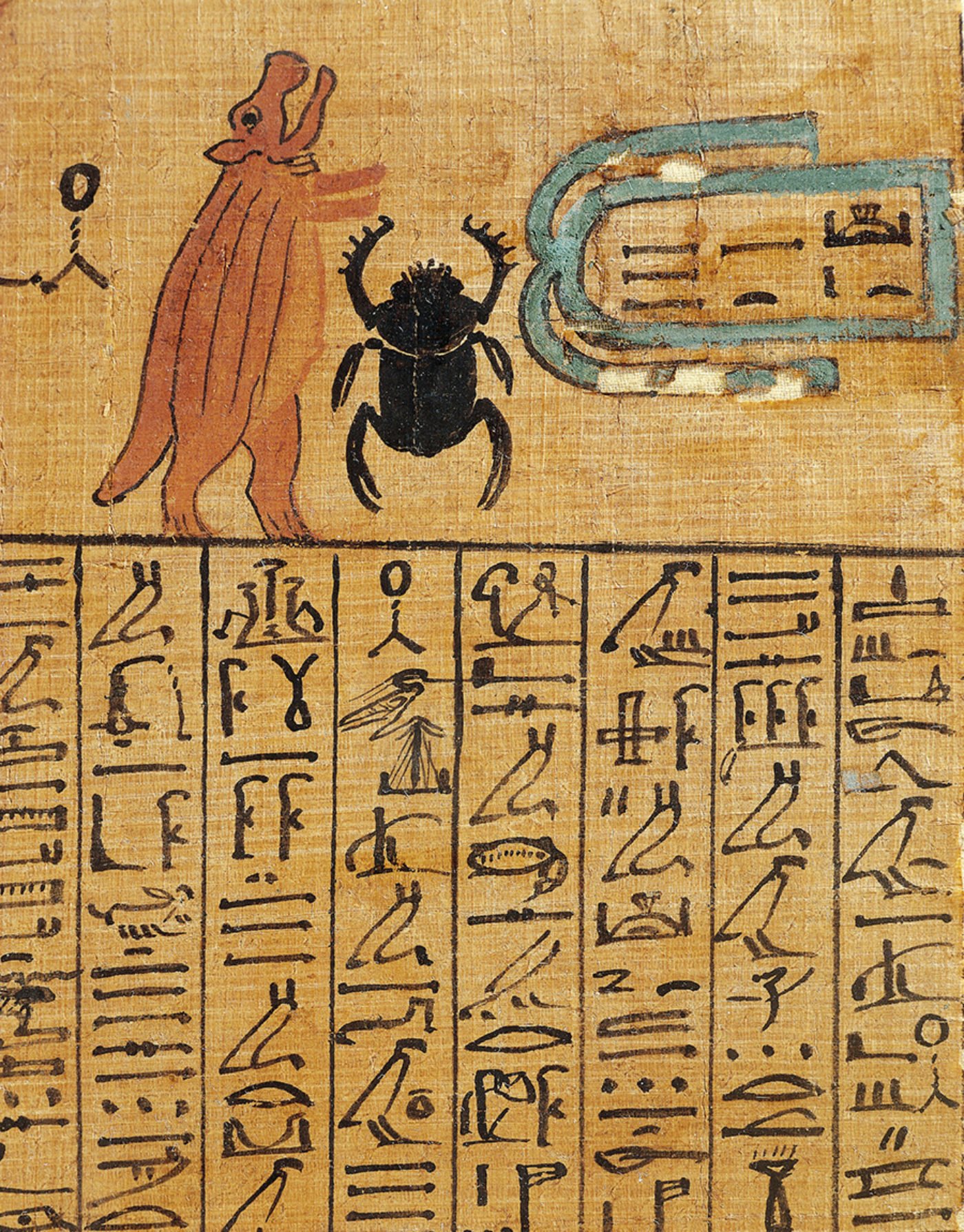

The magical tradition, in the West at least, is unbroken. According to Stephen Skinner, a prominent latter-day practitioner, this tradition can be traced to millennia-old Egyptian magic, which was formalized and syncretized by the Greeks in Alexandria around the third century bc. This system combined Egyptian apotropaic spells (i.e., those designed to thwart evil influences) with Greek spells intended to fulfill more personal aims (i.e., sex stuff). The resultant Greco-Egyptian magic was codified in a series of papyri, some of which survive to this day.

When a sizable number of Jews fled to Alexandria after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 ad, Jewish magical formulae, divine names, and figures such as King Solomon were added to the practice. (This probably inspired the Talmudic adage: “Ten measures of magic came into the world. Egypt received nine of these, the rest of the world one measure.”) Not long after, Christianity arrived in Alexandria and brought its own elements to Greco-Egyptian magic, the most consequential of which was the reclassification of pagan gods as evil spirits.

The thaumaturgic melting pot burbled away in Alexandria until the city fell to Muslim armies in 641 ad. Refugees smuggled the Greco-Egyptian tradition into Constantinople. Along the way, Mesopotamian elements were incorporated; now Nebutosualeth rubbed shoulders with Abraham and Anael. In Constantinople, Greco-Egyptian magic came to be known as Solomonic magic. This was not spooky saturnine devil worship; Solomonic magic was practiced in service to a higher power, with the aim of binding ill forces and putting them to good use. The techniques were passed down from master to pupil in an underground apprenticeship system until Constantinople, too, was sacked in 1453. The magical tradition hit the road again, this time traveling to Italy, where it was translated into Latin and became the Clavicula Salomonis, or Key of Solomon. As it spread throughout Europe, the Solomonic system fractured into many derivative, incomplete, and often deliberately misleading grimoires, which were acquired in secret, sometimes under threat of death.

Perhaps the most important takeaway about magic, I came to understand, was this: If it were simply made up, then each successive generation of mages would have invented new, fanciful, and wildly divergent systems. But the opposite is the case. No worthwhile magician has ever dreamt up his own practice. At best he modifies or adds to an existing one. The methods of invocation, the forms of the circles, the vestments, even the incenses have changed little, if at all. Magic is inherently conservative in this way. Wizards operate within a canon.

I cracked an eye and saw that the windshield was frosted over. I unbuckled my seat belt, kneaded my face, and took a moment to reorient myself. It was day one of the faire, and I, along with King, his second wife, Jenna, and his childhood friend Andy, had bedded down in the cab of a rental SUV after joining the line of vans, recreational vehicles, and buses queued outside the fairgrounds.

A thin moon was still shining when I exited the vehicle gingerly so as not to wake the others. To the west, tiered silhouettes of blue mountains receded in visibility from ultramarine to smoke-gray. Short, buff grasses grew in the valley along with a few gnarled trees. Eventually my companions emerged, shaking the sleep from their bodies, and huddled around a glass pipe. Jenna appeared to be Canadian through and through—tall, polite, relentlessly sanguine. Andy, on the other hand, wore a beard sans mustache, and had about him the squat, condensed aspect of a fantasy race forced to live underground. “Andy and I have known each other since we were adolescents in Memphis,” King explained. Andy had aided him in his earliest experiments, serving first as something of a guinea-pig-cum-amanuensis. “He’s a wonderful counselor,” King said. Andy took a hit from the pipe, chewed it vigorously, and exhaled.

Once we were allowed into the grounds, we claimed a piece of choice real estate at the intersection of two narrow, hay-strewn lanes. In spite of the temperature, a festal gaiety was rising. Groups of friends were erecting tepees next to camper vans overflowing with grubby children. Ponchoed neobeatniks rambled everywhere. We set to work assembling a cluster of personal tents, communal tents, bartering booths, and a gazebo.

As soon as the gear was readied, King donned his black, waterproof wizard’s robe. He took me aside and whispered in a low, urgent tone that now was the time to drop acid. We swallowed paper blots that King had procured from an associate.

King showed me into his business tent, where he would be giving tarot readings. Inside stood a few folding chairs around a small table covered with sequined fabric. Occupying the space between our faces were kitschy rubber bats hung from strings.

“A lot of this psychedelic consciousness-alteration stuff that will go on at this thing—I think that it’s important to keep this separate from the idea that there’s mystical reality to such trips,” King said, lighting three electric candles. “It’s entertainment of sorts. It’s illuminating sometimes. But what you experience on trips aren’t truths.”

In between tarot sessions with dreadlocked fairgoers, King gave me a better sense of his political and moral framework, which turned out to be a kind of spiritual libertarianism. “While there may never be any agreement on what violates divine laws,” he told me, “there can be a general consensus that it is wrong to suppress free will.”

Though King does not believe in Christian ontology, he sees demons as being evil nonetheless, because they hinder individual will. They exert a nearly constant and entirely negative influence over us. Many really are the gods of antiquity; others are the manifestations of large-scale sociohistorical forces. Think of them like decentralized movements, King said, like changes in the air you feel to be taking place on a vast scale, even as you have no idea where they came from or what they portend. These demons are directors and products both. They are the impetus as well as the sum of all the actions taken by those who’ve sworn allegiance to them in their various forms: financialized capitalism, say, or the politics of resentment. Really, anything you might call up from the scrying mirror of your phone screen.

This is why the wizard acts as an exorcist, never a supplicant, King explained. He wants not to acquire the influence of these spirits, but to be rid of it. He binds them in order to free himself. This is the ultimate task of the magician: to discover his uncorrupted will and fulfill its purpose.

Hours later, we closed up shop and crossed over to the communal tent. By now the acid was making me squint as though my surroundings had been translated inexpertly into my native tongue. It was also emboldening me. I asked King: “Why do bad things happen to you if you’re this all-powerful magician? Why aren’t you filthy rich?”

“If that’s really the test of it,” King answered, “then you can look at—well, what happened to Jesus?” His voice was quieter than usual, but otherwise he appeared to be suffering no ill effects from the LSD. “Jesus is hanging on the cross, and the thief next to him is saying, ‘If you’re God, why can’t you stop this?’ ”

He frowned and continued: “This is my personal calling. When I was younger, I wrote out all seventy-two seals in my own blood. The pact of it was that I would be the world’s greatest magician for the period of my life. . . . If I were to abandon it at this point for whatever reason, I don’t feel like that would go over very well. I don’t really feel like I’m allowed at this point to back out.” He paused to swallow. The matte, phosphorescent sigils painted onto his robe appeared to palpitate in the low light.

The next day, sitting around the tents and waiting for opportunities to barter, I asked King to rehash his most memorable conjurations. He told me about how he caused the 2003 San Simeon earthquake, in which two women were crushed to death by a collapsing brick edifice. “Maybe I’m just callous,” King said. “I don’t feel any guilt over that. I don’t feel like the spirits are explicitly bound from doing any harm to people on account of my instruction.”

Then there was the time he tried to get a demon to assassinate the noted skeptic and sleight-of-hand master the Amazing Randi. “I proposed to conjure his fatal demise by the power of the demon Forcalor as a sign to the world that magic wields true power over even life and death,” King explained. It did not work. The spirit “agreed to do only as was required of it, and it was required only to slay those who pose a threat to me, which Randi did not.”

When dusk fell, King and I found ourselves alone at the campsite. This was my chance. I wondered aloud whether now wasn’t a good time to break out the real sorcerous implements. King said he’d packed his crystal ball in case of emergency or special occasion; he supposed this qualified. Inside his business tent, he placed the quartz sphere—yellowish, translucent, and roiled with small bubbles—atop his scrying board, which was as wide as a lazy Susan and carved with the sigils of archangels and demon kings. “This apparatus is a cosmology,” King said, explaining how the inner rings of infernal power were constrained by the outer rings of heavenly influence. “It is a map of the universe.”

We drew our heads over the board. Dancing in its high polish were the reflections of ten candles positioned around us. “So what exactly should I be looking for here?” I asked, my eyes trained on the crystal as it sparkled faintly.

“We are summoning angels,” King said. He took several deep breaths. Somewhere nearby, a guitarist attempted to play ZZ Top’s “Sharp Dressed Man” and failed. “This is visionary and revelatory magic,” King said. There wouldn’t be any writhing demons—but still, a disincarnate force was about to enter our world. It was better than nothing, anyway, and “emphatically not a gypsy scam,” King added.

I wriggled nearer. My heart was twitching like bait on a line.

“I call the spirits to the crystal, and they provide me with answers,” King went on. “Divination is not like looking at a TV’s reception. I call upon the spirit to give me inspiration and to allow me to use the crystal as a kind of antenna, a receiver.”

I stared hard into it, searching for patterns, data—anything to process.

“I have little control over the content,” King said. “A central feature in all of this is the recognition of an awareness and intelligence on the other end of the line.”

I thought perhaps I was meant to treat the crystal like a Magic Eye puzzle. I unfocused my vision the better to spot the secret message. “Uhh,” I said. “What should I ask them? It?”

King’s voice dropped to a whisper. “Generally something within the domains of the planetary spirits,” he said. “Work, family, the unknown. Things that concern the fates of people.”

“Okay—work,” I said. “Do work.”

King began his rapid susurrations. “O thou mighty, great, and potent angel Samael, who ruleth in the first hour of ye day . . . I, the servant of the most high God, do conjure and entreat thee in the name of ye most omnipotent and immortal Lord God of hosts . . . ”

There were a few moments of silence. Then King told me: “I see snow and rain swooping down from mountaintops. I see small houses along the mountains . . . and there are bridges and people and things moving about. . . . ” Almost like an idealized Swiss village, he explained. There was a specialty market. “What I see in relation to your career . . . that your career finds a niche kind of market that’s available to people who are interested in that. It looks like an upscale kind of place. . . . It’s there, but it’s not necessarily for everybody.”

I withdrew my eyes from the crystal. I stared at the balding crown of King’s head. He was proffering details like a man stepping tentatively onto thin ice. I was growing, shall we say, impatient. After spending hundreds of dollars and traveling thousands of miles—here be a wizard divining for me the esoteric truth that print is the new vinyl.

“Well!” I huffed once King had gone quiet. “Can you do people now?”

King repeated the ritual with slight variations, then described what he saw: “The bird is a long-beaked, inquisitive-looking bird. Maybe a waterfowl of some kind. . . . It’s out of place. My interpretation of this, just from looking at the image, is that this is a person you’re going to find who is out of place.” His voice gained in volume and confidence. “Someone who seems to have their own element that they belong in. And they’re definitely not in it.”

I tried looking into the crystal again. This time I placed my eyes centimeters from it, and squinted. I saw—or thought I saw—something begin to resolve itself out of the points of light. Something small but budding, like a wad of paper uncrumpling, sullenly radiant and monochrome—like a sequence out of a silent film. I became aware of a warmth intensifying along my neck and shoulders, as though a large magnifying glass were concentrating sunbeams onto me.

“This person is wearing some kind of mask, disguise, or obscurant to their actual face,” King continued. It was as if one part of his mind had broken off from the rest and was addressing me now. “If it’s a person that you meet on the internet, their picture might be a different picture.”

The figure in the glass swam before me like a jellyfish, expanding and contracting. It seemed primal and voracious, ready to envelop and subsume. I felt an energy approach, with a silent but hair-raising presence, as if hundreds of boxy old CRT televisions had been powered on. The atoms between my ears began to thrum at this same frequency.

“There’s someone out there who’s perhaps there for you and good for you, but is not perfect,” King said. “It’s one of those things—it could be good for you, it could be the nightmare of your life.”

King went still for a minute, two minutes. With annoyance and a touch of regret, I felt my consciousness returning to me. But my body now sounded an alarm. I experienced a sharp, cramped pain in my chest, like it was proving too small for what it contained.

“You got all that from the crystal ball?” I grimaced, and coughed up a laugh.

“Indeed I did,” King said. His words were briefly visible in the tightening chill. I watched him watch me. He seemed to have increased in vividness. He looked satiated.

We exited the tent. There would be time for further revelations, King assured me.

In the weeks that followed, I had difficulty sleeping. Concentrating, too. I was uninterested in anything other than the occult. Most nights I spent poring over the grimoires and magical treatises King had given me. You could say I was obsessed.

Fall turned to winter, then spring, and the outside world locked down for the novel coronavirus. This affected me not at all, as I was already hunkered in my apartment with my tomes, reading and tinkering, attempting first the simple rites of Abramelin before swimming into deeper waters. The timelessness of these practices consoles, or consoled me at least. In performing them, I discovered a deep and abiding thirst for the hermetic knowledge they promise. This thirst drove me to acquire more grimoires, and the grimoires intensified my thirst in turn. Ceremonial magic confirmed in me my belief that nothing so enthralls as correctly arranged words.

Occasionally I video-chatted with my family. “Aloof,” “mean”—my mother said she was growing concerned about my behavior. She seemed to gawk—not at me, but beyond me, like there was something over my shoulder. Zealous as she is, my mom begged me to seek out a Catholic exorcist, for research purposes if nothing else.

I scoffed at this, was affronted by it—exorcism!—and so paused our communication. By now I had come to share King’s disdain for that whole puke-and-rebuke spectacle. Exorcism was no more than a closed circuit of motivated reasoning, a performative placebo whereby some “deviant” or “malcontent” was theatrically castigated, then reintegrated into his or her community. Demons are real, King told me, but traditional exorcism is not. “The idea of demonic possession as a facet of overtaking the will is something that occurs not in a church-and-exorcist setting,” he said. “Think of all the young men who thought it was cool to join the Nazis.”

That kind of possession I could believe in. Not some fed up Thuringian washerwoman hocking loogies at the parish priest, but an individual who has been so gripped by an enfolding ideology that the boundary between possessor and possessed is erased. Horrible, but also wonderful; an outrage, a revelation, and in the literal sense of the word, an ecstasy. The hidden knowledge has been opened up in you. You can now perceive the web of forces that have been constraining your world. At last you understand the motives behind everyone’s actions. As with a drug, you have been liberated.

Even so, I still wanted to believe in the bodily aspects of possession. Back and forth I went on this, limping as though shackled to an uncooperative three-legged-race partner, until finally I sucked it up and called a few parishes, asking after priest-exorcists who had gone public with their ministries. From what I could gather, these men tended to be either Barnumesque publicity hounds or else quasi-embarrassed underground practitioners. Most turned down my requests for interviews. The only one who did not asked that his name be withheld.

He told me that every diocese is required to have at least one specially trained priest who can perform exorcisms, although this rule is frequently ignored, and cases of true demonic possession are vanishingly rare. Still, demand for exorcism in the United States and around the world has never been higher. About fifteen years ago, there were roughly fifteen American priests approved to perform exorcisms. Today, there are more than one hundred.

Why the increase? Priests blame Satan and his works, of course—but also a deteriorating American culture whose God-shaped hole is getting filled with yoga, transcendental meditation, New Age pantheism, Wicca, Santa Muerte, gender theory, Reiki, and other heathen practices. Our society is hungering for spirituality but satisfying this hunger in all the wrong places. Seekers are falling prey to evil spirits. No matter how innocent you believe your intentions to be, when you pick up the healing crystal or the Ouija board, you are broadcasting a desire for a relationship with devils. You may not believe in them, but they believe in you.

That’s what a possession is, the exorcist I spoke with said. It’s a relationship. And it’s not equal.

For a more medically rigorous explanation, I turned to the clinical psychiatrists. Some of them assert that the criteria for discerning spirit possession are based on a genuine syndrome. The symptoms are fixed and have been for centuries: aversion to sacred imagery and objects, sudden competency in foreign languages, knowledge of hidden things and private information. Most importantly, possessed individuals will periodically enter a trancelike state during which the presence of an independent entity is made known.

The majority of these cases have a psychiatric or neurological explanation: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, drug or alcohol withdrawal, dissociative identity disorder. But should a medical professional be unable to pinpoint a diagnosis, in steps the exorcist. He asks the afflicted: What brought you here? Did you dabble in the occult? In subjects you might not have realized were occult? Do you carry a grave open wound? Have you sought relief from whichever whispering angel best promised it?

Call it victim blaming, but this belief about possession has persisted for millennia: No one can be possessed without some degree of cooperation. You can’t catch possession like you can a cold. You don’t become the puppet of a higher creature without a bit of collaboration on your part. It doesn’t matter if you instigated it unconsciously; an unconscious relationship is all the more powerful for it.

Why would demons do this, try to commandeer humans? According to scripture, they are both superior and anterior to man. Though not made in God’s image, as humans were, demons are nevertheless persons in that they have consciousness, intelligence, and will. They are warped angels—spirits of wonted pride and hurling defiance. These fallen angels resent God, the hierarchy of heaven, and all that was, is, and will be. As such, they labor tirelessly to unravel the work of the Father. But demons themselves are ontologically empty, and they empty all who embrace them. They are deconstructionists in the truest sense, because they long for nothing—literally nothing; nil but the ultimate demoralization, disintegration, and self-destruction of every last atom in His Creation.

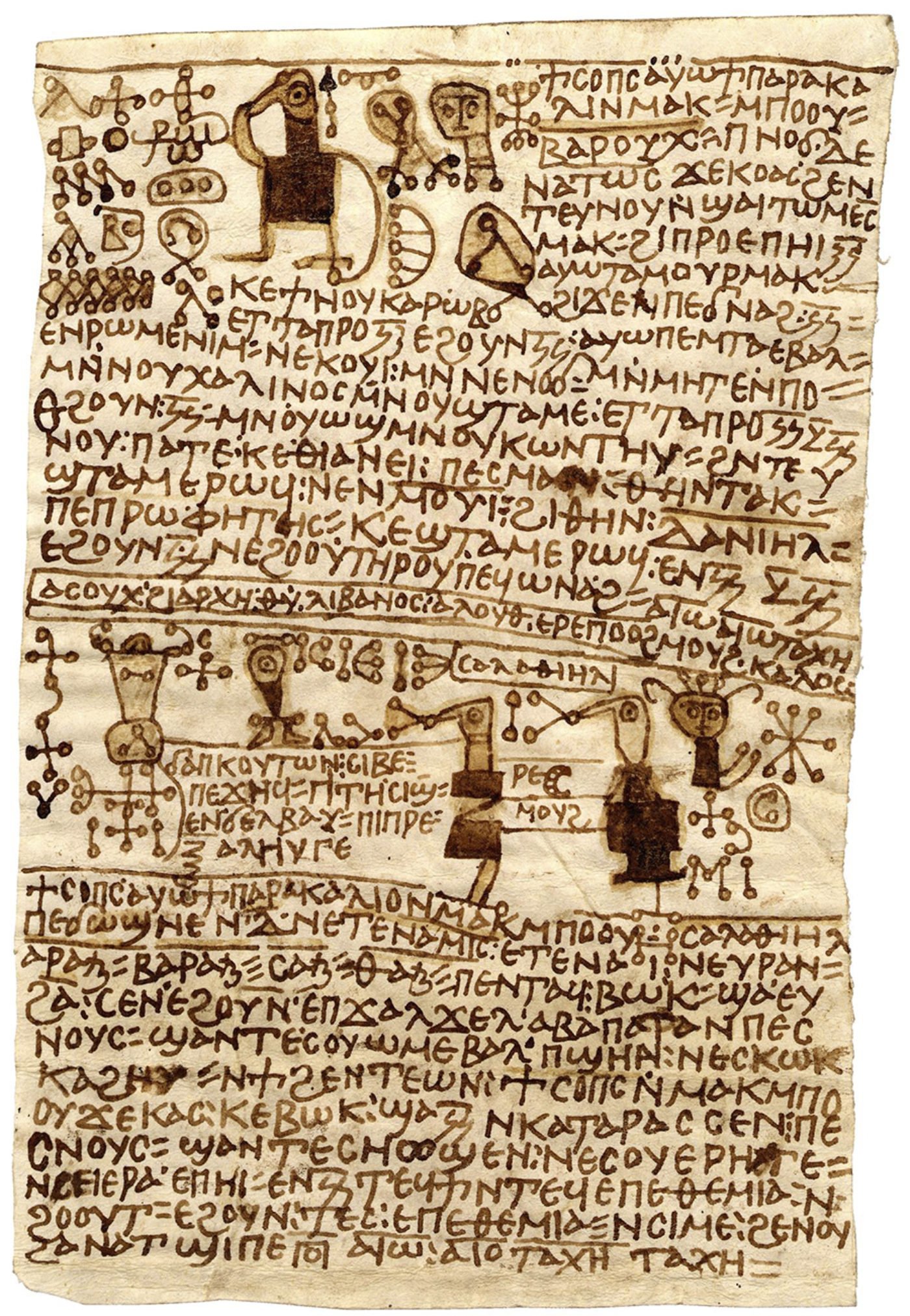

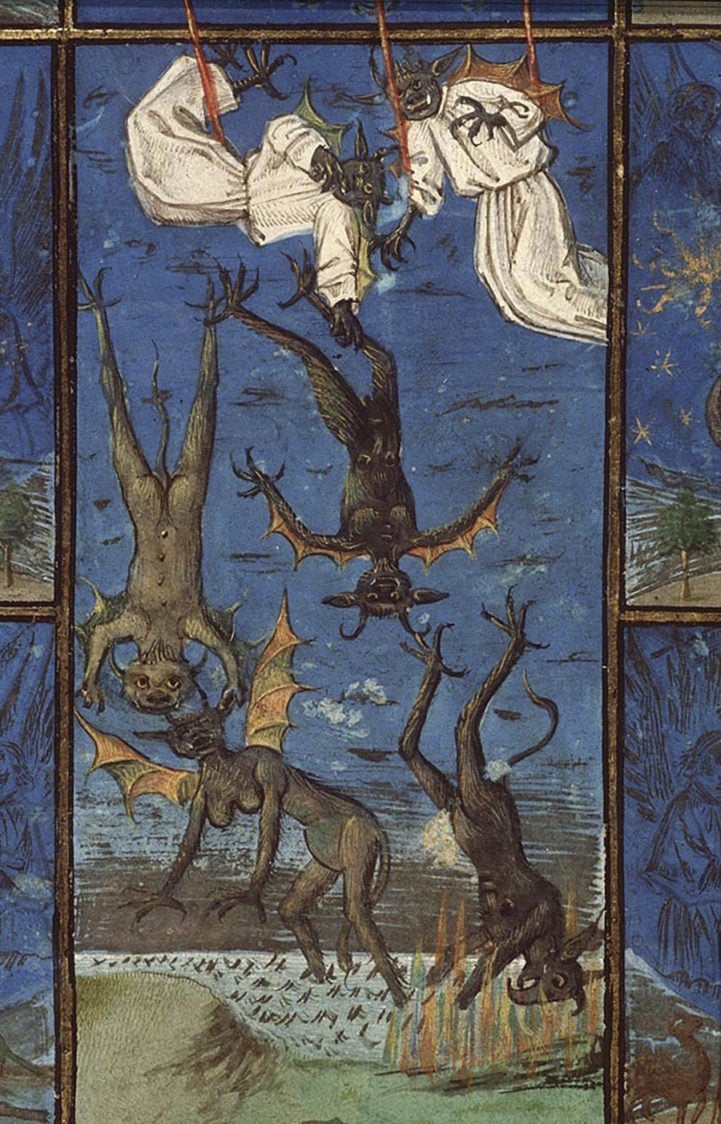

Scene from a fifteenth-century illuminated manuscript. Courtesy the Royal Library of the Netherlands

I kept up my video correspondence with King and, more than a year after our first meeting, got him to agree to meet again. I was in need of his help, his encouragement—really what I needed was to see my mentor work. Plus I needed the company. I’d been talking to no one else, just King and the spirits, and the latter conversations were not so much cathartic as painful; the Hebrew and Greek words had strange geometries, spiky mouthfeels, and they passed out of me fitfully.

The one thing I could count on still was interrupted sleep. Most nights I woke to silence, albeit a tenanted silence, like tinnitus. A tangency was in the room with me, I knew. It had been there for quite some time, watching me. To dispel it, I had to roll over and acknowledge it—but I couldn’t. I would lie on my side and listen to this rasping, insistent, almost angry noise. It had a harsh sibilance, like an electric razor or a beehive.

Lying like that, I’d wonder: If I were a tricksterish nihilist intelligence, self-consuming and hell-bent on disarray—wouldn’t I try to invert the expected? Wouldn’t the real diabolical trick be to convince my captive audience that the cautionary tales are, in fact, bunk? That there’s no such thing as possession, ergo no devil, no redeemer to save us, no Hell? Wouldn’t I want them wondering, Isn’t this exactly what a demon would want me to think?

When the day came, I arrived at King’s modest exurban bungalow, where he had a surprise waiting: a rosy newborn named Franklin. We took turns dandling the boy on the back porch while talking into the night, about lockdowns, about social media, about King’s four other children. “I hope they don’t hate me, but I don’t know what she tells them,” he said of his ex-wife. “I don’t get any contact with them. I don’t think they’ve read the books.”

Around midnight, King escorted me into his living room, which was heavily carpeted, ringed with his paintings, and cluttered with baby mats and bead mazes. At last, I thought. This is it. He invited me to take a seat on the sofa, and asked me to close my eyes.

When I opened them, I saw King approaching with a wooden box balanced in his hands as though it was explosively volatile. From it he withdrew silk tissues, followed by gold, silver, and aluminum pucks—the talismans required for Solomonic magic. He arrayed them on his coffee table and explained in great detail how he consecrated each. “This one is for discernment,” he told me. His voice was dreamier than usual. “Knowing people’s true intentions. I did that with a Dremel.”

He showed me his alabaster incense holder, his lionskin belt, his aspergillum, his ceremonial chalk. “This is proprietary knowledge,” King insisted. “You get to see it because you got to know me in a different way.”

I leaned forward, creased my face, and awaited revelation. From what or for whom no longer mattered. I was going to hear without asking and accept without scrutinizing.

“This is like a scrapbook of my life, in a way,” King said to himself as much as to me. “It spans from 1999 till now.” He straightened up and beheld his talismans. Then he began returning them to their box. His powerful and begrimed hands cradled each item as delicately as a bird’s egg before squaring it away.

I sank back into the couch. Sensing my confusion and despond, King made clear: “There’s no purpose to being the ritual fiend. I say this as a person with considerable occult experience. I like to think of this”—he gestured at his box—“as a labyrinth. You have a labyrinth. It’s there to explore and understand. But it might be that the labyrinth itself doesn’t have a purpose.”

“But,” I began.

“You can’t just demand that they show themselves,” King answered.

I bugged my eyes, held up my notepad.

“Oh, trust me, if I thought that I could actually do that, and successfully do it—there’s a Rothschild somewhere that has that same desire. If I really felt like I was that confident in it, I’d book myself at the Excalibur and dress up like Merlin and advertise King Arthur’s Demon Show.”

I exhaled loudly. What about the gauntlet laid down in the blog: “If you doubt me, come and see?”

King winced, blinked a few times. “The spiritual is not really in the same world. These spirits don’t have physical existence; they have intelligence, but they don’t have form. If we are perceiving form, even if it seems concrete. . . . ” King stopped to consider his words. “Which is what I think the spirits do—tap directly into the part of your brain that is actually controlling visual perception. They could create any kind of image that you want to see. It is just your brain that creates that image. So a spirit that’s given permission to manipulate that part of your brain—it can produce an image of ten beer cans sitting here that will look just as real as any other beer can. But you have to consent to give that level of control.

“Not only do you grant them the ability to manipulate your perceptual system,” King added, closing his box, “but your trajectory in life. You’re allowing yourself to be guided down a path.”

“I have to consent first to being guided down the path?” I asked. “Is that what you’re saying?”

“There are billions of people in the world who, if you told them, ‘I could provide you with an authentic experience of the spiritual’—they’d give up appendages, family members. There’s nothing people wouldn’t do to have proof that there’s something beyond.” King nodded, collected his thoughts. “Ultimately, in life, there’s going to be some point at which the spiritual realities are made clear to you, and you will have the option to accept that and have faith, or to deny it.”

“But you can’t put me on the path?” I asked with no little exasperation. “Is that what you’re telling me?”

“I might not be able to say, ‘I’ll bring the demon to your house to show you.’ But you can invite the demon to your house to find out.”

King beckoned me into his library. He had more advanced literature to share. “There’s a reason it’s called the Key of Solomon,” he said. “It unlocks the door. You have to walk through it.”

I pored over King’s contracts and grimoires and tried not to be daunted by the amount of transfiguration still ahead of me. If I was going to encounter a demon, then I would need to become much more adept at putting the right words in the right order. Only then, and at last—eyes fixed on the scrying mirror, cheek by jowl with God and the devil—might I glimpse a figure of absolute alterity. A truly apocalyptic event, ecstatic and awful, embodied right there for anyone to see. The powers are real. I resolved to keep looking for myself.