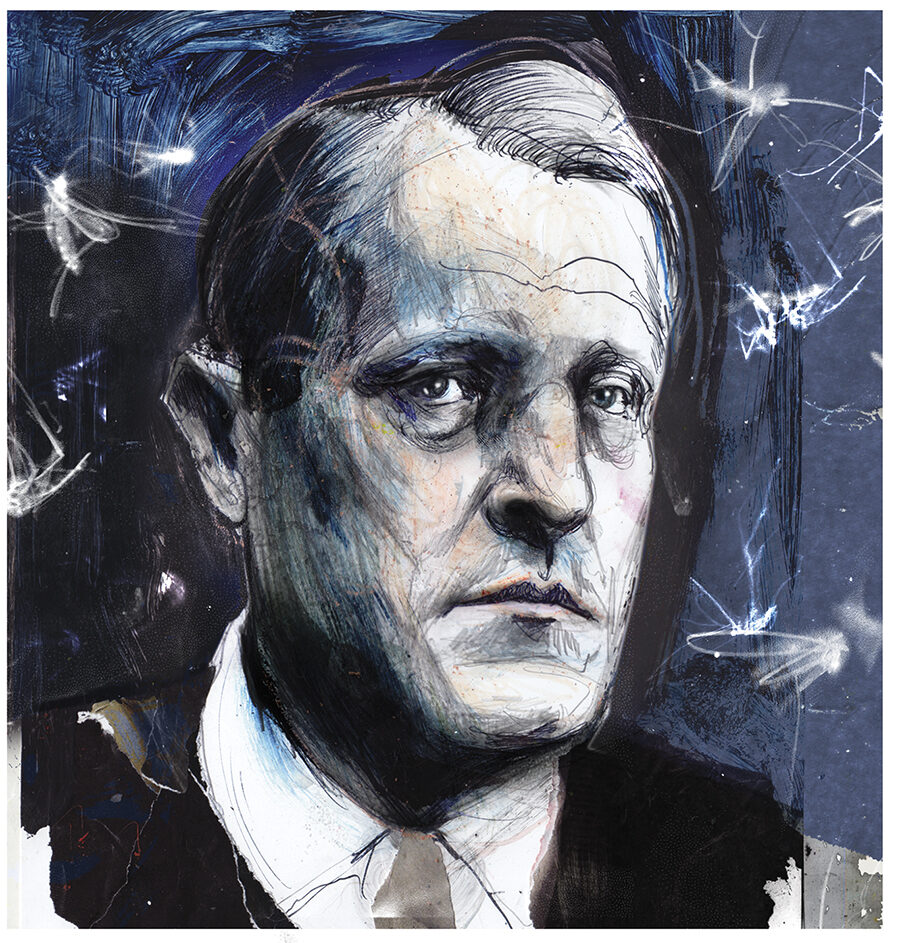

Illustration by Zé Otavio. Source photograph © Philip Mechanicus/MAI

Discussed in this essay:

A Guardian Angel Recalls, by Willem Frederik Hermans, translated from the Dutch by David Colmer. Archipelago. 511 pages. $20.

An Untouched House, by Willem Frederik Hermans, translated from the Dutch by David Colmer. Archipelago. 120 pages. $16.

The Darkroom of Damocles, by Willem Frederik Hermans, translated from the Dutch by Ina Rilke. Pushkin. 411 pages. £9.99.

Beyond Sleep, by Willem Frederik Hermans, translated from the Dutch by Ina Rilke. Pushkin. 312 pages. £9.99.

The work of Willem Frederik Hermans suggests what might have happened if Graham Greene…