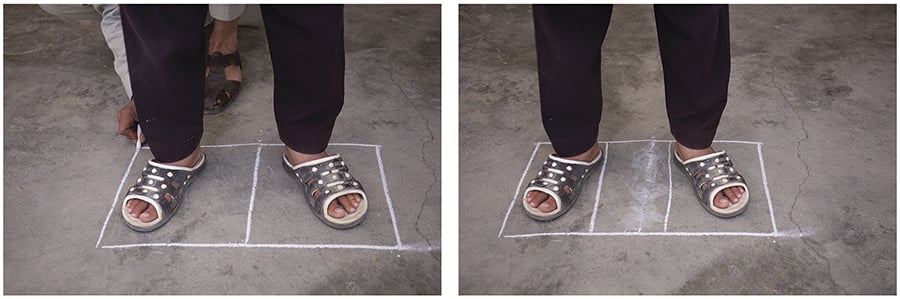

“Chalk Drawings,” by Aziz Hazara © The artist. Courtesy Experimenter, Kolkata, India

With David Unger’s brilliant translation of Mr. President (Penguin Classics, $17.99), by the Guatemalan Nobel Prize–winner Miguel Asturias, readers are newly invited to encounter the author’s extraordinary and darkly prescient satire of life under brutal dictatorship—a fiction begun in 1922, finished in 1933, and not published in wide circulation until it appeared in Argentina in 1948.

This edition, which includes a foreword by the Peruvian writer and fellow Nobelist Mario Vargas Llosa, and an introduction by the eminent scholar Gerald Martin, endeavors to confirm Asturias’s position as a founding figure of Latin American literature. What makes Mr. President extraordinary is not simply its enduring subject, but also its operatic and inventive multiform style: as Martin points out, it’s a novel “very like a play, a tightly concocted drama (at times a theater of marionettes),” equally cinematic and poetic. It is reminiscent of Kafka and Beckett in its surreal flights within the consciousnesses of the mad or dying, or within the narrative of myth, such as the chapter entitled “Tohil’s Dance,” which, as Vargas Llosa points out, “is more like a painting or mural inspired by the distant ancestors of the K’iche’ Maya archaeological past.” Tohil, the name of the Mayan fire god, was initially meant to be the novel’s title.

Asturias’s canvas is Shakespearean in scale—the story opens with grotesque beggars on the street, but leads us on to the thugs and wenches of the Two Step Tavern, the whores of the Sweet Enchantment brothel, the brutalized prisoners and their warders, the urban aristocrats and rural bourgeoisie, and the military, police, and administrators of the president’s regime—all of them, regardless of their status, contorted in terror by their leader’s wrath and corrupted in their very souls. We even visit, on occasion, the president himself, whimsically murderous.

The plot takes many turns, but its outline is straightforward: A mad beggar, Pelele, strikes and kills one of the president’s henchmen, Colonel José Parrales Sonriente, whose death provides an opportunity to charge and execute the retired general Canales and the lawyer Carvajal. The president himself sends his confidant, the novel’s protagonist, Miguel Angel Face—described repeatedly as being “like Satan . . . both good and evil”—to warn Canales of his impending arrest and encourage him to flee, so that he may be caught on the run and thereby implicate himself. But Angel Face falls in love with the general’s daughter, Camila, and concocts a scheme to let the general escape while he kidnaps her. Thereafter, Angel Face joins the ranks of the doomed, along with the general and countless others.

The novel’s vision is relentlessly dark—as the sinister judge advocate upbraids his housekeeper, “The first thing you should know is that in my house, you don’t offer hope to anyone, not even to the cat”—but its execution is exhilarating, daring, even wild. Asturias’s boldness is repeatedly arresting, and his descriptions unforgettable. Here, but a single moment:

Angel Face waited by the door, unaware of what was happening around him. Dogs and buzzards fought over a dead cat in the middle of the street, directly across from an officer who watched the ferocious struggle from a barred window, twirling the ends of his moustache. Two women drank fermented cider in a fly-infested corner shop . . . A butcher walked between a group of boys lighting cigarettes: his apron full of blood, his shirtsleeves rolled up, and a butcher knife near his heart.

Such electrifying vividness animates every page. Not without good reason does Vargas Llosa hail Mr. President as “one of the most original Latin American texts ever written.”

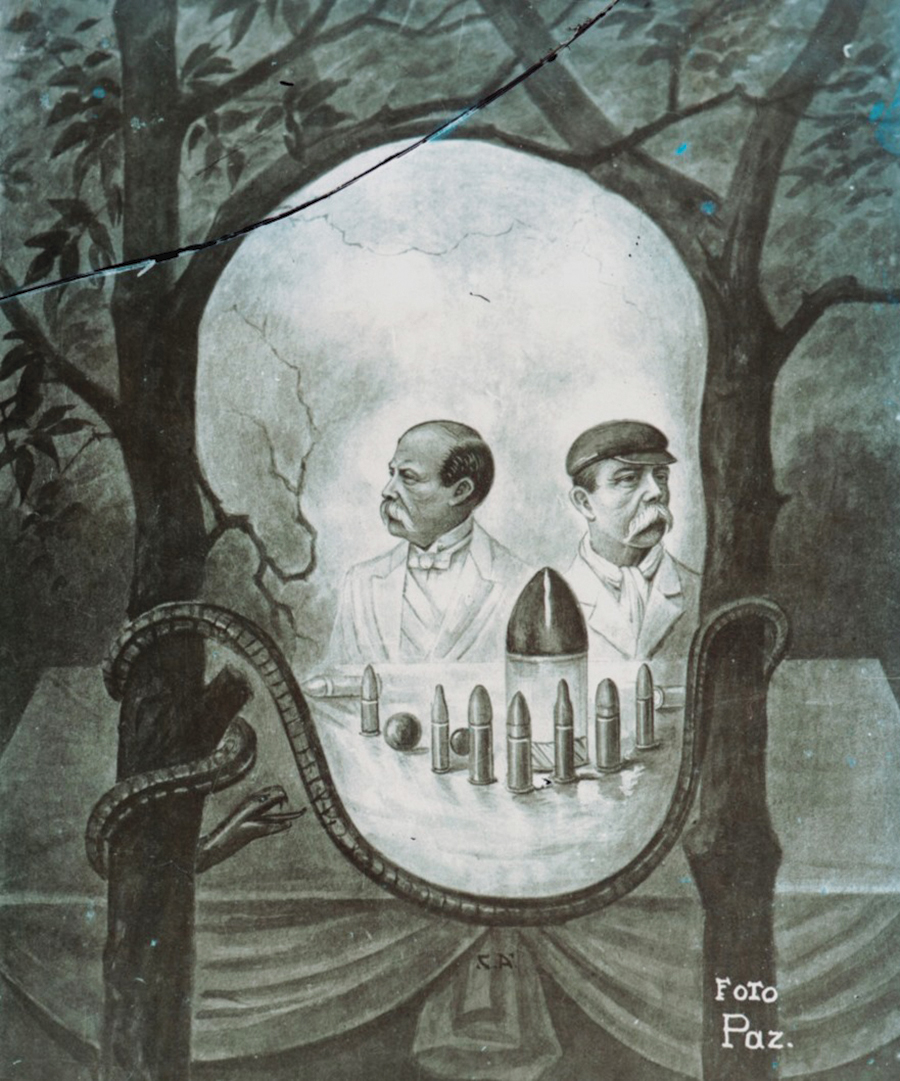

A photograph of a caricature of the Guatemalan president Manuel Estrada Cabrera, 1920, by Juan José de Jesús Yas

Jamil Jan Kochai, the author of the acclaimed novel 99 Nights in Logar, returns with a remarkable collection, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories (Viking, $25.49). Kochai, an Afghan-American writer, shapes and reshapes his material through a variety of formal techniques, including a fantasy of salvation through video gaming (“Playing Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain”), a darkly surrealist fable of loss (“Return to Sender”), a life story told through a mock résumé (“Occupational Hazards”), and the story of a man’s transformation into a monkey who becomes a rebel leader (“The Tale of Dully’s Reversion”). Like Asturias, Kochai is a master conjurer.

The collection’s cohesion lies in its thematic exploration of the complexities of contemporary Afghan experience (both in Afghanistan and the United States), and in the recurring family narrative at its core: many of the stories deal with an Afghan family settled in California. The patriarch, retired after a debilitating injury, suffers constant pain. He was once a young mujahid in his native Logar, fighting alongside his younger brother, Watak, who was killed by the Russians. His family comprises his wife and aged mother, two young daughters, and two adult sons.

Some pieces, such as “Occupational Hazards,” belong to this father, through whom we experience war’s brutality firsthand: in the résumé’s thumbnail description of “1980–1981, Mujahid, Deh-Naw, Logar,” we learn that his

Duties included . . . burying the tattered remnants of neighbors and friends and women and children and babies and cousins and nieces and nephews and a beloved half-sister named Gulapa.

Then in “1982, Reaper, Deh-Naw, Logar,” after discovering the death of Watak, he spends “the entire night digging graves and collecting limbs; seeking blood; seeking death; seeking the solitude of gunfire . . . deciding to live, to leave.”

Kochai also brings us the women’s perspective. In “Enough!,” Rangeena, the patriarch’s mother, relays her litany of grievances—about her suburban American lifestyle, her son and “his viper of a wife,” her medications, her losses—breathlessly in all but a single sentence, before rising from her chair in an ill-fated attempt to return to Logar that is simultaneously bathetic and poignant.

But many of the stories attend chiefly to the sons’ generation, to characters of around Kochai’s own age. Marwand, the child protagonist of 99 Nights, narrates both “Saba’s Story,” in which his father returns to his native village to try to reclaim his land, and “Waiting for Gulbuddin,” in which he and his brothers, on a visit to Logar, are left to await their uncle by the grave of their late uncle Watak.The narrator of “Hungry Ricky Daddy,” a university student, recounts the story of his little brother’s best friend Ricky Daddy, “whose real name was Abubakr Salem,” with whom both brothers share an apartment, alongside eight other Muslim and South Asian students. A dark account of Ricky Daddy’s fatal hunger strike, this story is, like so much of Kochai’s work, seamed with sharp wit, and often hilarious. The surreal reality of the boys’ lives involves watching Gilmore Girls and squabbling over a pet rabbit and the microwave, as well as learning about “the Brotherhood, the intifada, the birth of Hamas, and the Oslo Accords.”

Elsewhere, Kochai slides more fully into the dreamlike. In the novella-length “The Tale of Dully’s Reversion,” Shakako Jani’s second son Dully—heretofore a graduate student—suddenly transforms into a monkey when he crosses her prayer mat at their home in Sacramento. In her attempts to effect his reversion, Shakako takes her son back to her old village in Afghanistan, where long-simmering feuds abound. Dully is trying to uncover the history of Hajji Hotak—who, according to his grandmother, was the first to die in unrecorded British massacres in Logar in 1897—when he is imprisoned in the Kabul Zoo. He eventually foments a monkey rebellion and escapes, returning to his family in Logar to lead an uprising. Unsurprisingly, this does not end well.

The title story, set in Sacramento, also uses the name of Hajji Hotak, but rather than a nineteenth-century martyr, he becomes the patriarch of a local family—“the father, code-named Hajji.” The story is addressed to an unseen observer who, rather like the Stasi spy in the film The Lives of Others, reports to an undisclosed authority on the family’s movements. Though the spy comes to accept that “the old man is no threat at all,” they cannot stop watching him and his offspring: “There’s too much left to learn.” Inevitably, the question will arise of what responsibilities accompany knowledge.

Kochai is a thrillingly gifted writer, and this collection is a pleasure to read, filled with stories at once funny and profoundly serious, formally daring, and complex in their apprehension of the contradictory yet overlapping worlds of their characters.

Nocturne, by Sholem Krishtalka © The artist

The contradictions of Seán Hewitt’s memoir All Down Darkness Wide (Penguin Press, $26) are no less intense, but less readily apparent. The author of a 2020 poetry collection, Tongues of Fire, and of an academic study of the Irish playwright J. M. Synge, Hewitt would not seem at first glance to be someone in peril. But his thoughtful and often exquisitely written memoir is both a gay coming-of-age and an exploration of the mental health crises affecting the LGBTQ community. More specifically, it is the story of his long-term partner Elias’s suicidal depression, of the toll this illness took on Hewitt, and of the revelations that it spurred.

Elias is not the first of Hewitt’s lovers to succumb to depression: a university boyfriend, Jack, died from the disorder. Hewitt’s recollections of their heady romance, which took place when Hewitt was just coming out as an undergraduate, are the stuff of Brideshead Revisited: a Cambridge May Ball (“He’s in a black tuxedo, standing in front of a dodgem circuit”), two young men climbing a tree at dawn, and Jack singing a Housman poem, his voice “joining the spring morning in the orchard, a little song of pleasure and grief so intertwined it would break your heart to hear it.” The nostalgic pleasure of these memories might well have been recorded a century ago: in both the rhythms of his sentences and what he relays, Hewitt places himself firmly in an established British literary tradition.

The dramas in this book, like the sentences, are less pyrotechnic than those of Asturias or Kochai, but they lack neither energy nor significance. The memoir at its core is about Hewitt’s relationship with Elias, starting with their meeting in Colombia, where both men are traveling alone. Elias is Swedish, and once Hewitt returns to the United Kingdom, their relationship seems destined to be long-distance, until they move in together: first in Liverpool, where Hewitt pursues a graduate degree, and subsequently in Gothenburg.

Hewitt is alive to the subtleties of their accommodations for each other. Of his summer with Elias in Gothenburg, he writes, “I sometimes worried that we were simplifying ourselves for each other. I became strangely conscious that I could only say the things I had the language for.” But chiefly he recalls that season as “an endless sunshine,” in contrast to which the darker season was a shock. Hewitt, focused on his studies of Gerard Manley Hopkins, did not at first appreciate Elias’s retreat into depression, until “it dawned on me that for weeks Elias had been asking me, implicitly, what life was for.”

The slide from depression to despair was swift, and on Elias’s twenty-seventh birthday, he ran away to his family’s summerhouse to attempt suicide. Mercifully, he telephoned Hewitt for help, and Hewitt and Elias’s parents rushed to his side. As Hewitt notes, “It is hard to account for the trauma of a thing that didn’t happen, hard to accommodate a fear based in an almost-event, a thing that might have occurred, but didn’t,” and yet, “he changed us both forever.”

The ramifications of Elias’s almost-action are multiple—not least, his institutionalization for some time. Elias comes to articulate that “even as a child” he had “an early knowledge that the future wasn’t a place he could live,” and “that of all the worlds he could see around him, none seemed made so that he could be happy in them.” This revelation is familiar to Hewitt: he too “had felt the same tenor of dread in childhood.”

Most straightforwardly, the memoir is the account of what happened between the two of them and its consequences—Hewitt’s increasing frustration with the impossible toll that Elias’s depression has on his own life. Their shared discovery of Karin Boye is another important strand—she was a queer Swedish poet who committed suicide in 1941, whose work the two men translate together. But Hewitt turns also to his own childhood and upbringing, to confront the degree to which “I had chosen to hide. I had lived a dual life, disconnected from my real self, so that by the time I emerged into adulthood, I was left with the task of rediscovery—or recovery.” Indeed, “queerness involved a process of becoming.”

Though a study of despair, the memoir is not despairing: through their poetry, Hopkins and Boye offer inspiration to Hewitt, also a poet. Considering queer lives, “both of them hoped—one with certainty, one with longing—that there would be a place for those people, a friend to watch them, a room with their name above the lintel.” But Hewitt goes further, insisting that “it should be here, the friends should be us, the father’s house should be our own.” His call, framed by the poets to whom he feels so profoundly connected, as well as by his own family, is radical, a fervent appeal for presence and belonging: “I would set a fire burning for them, I would bring them home.”