Illustrations by Xiao Hua Yang

The Other Rosalie

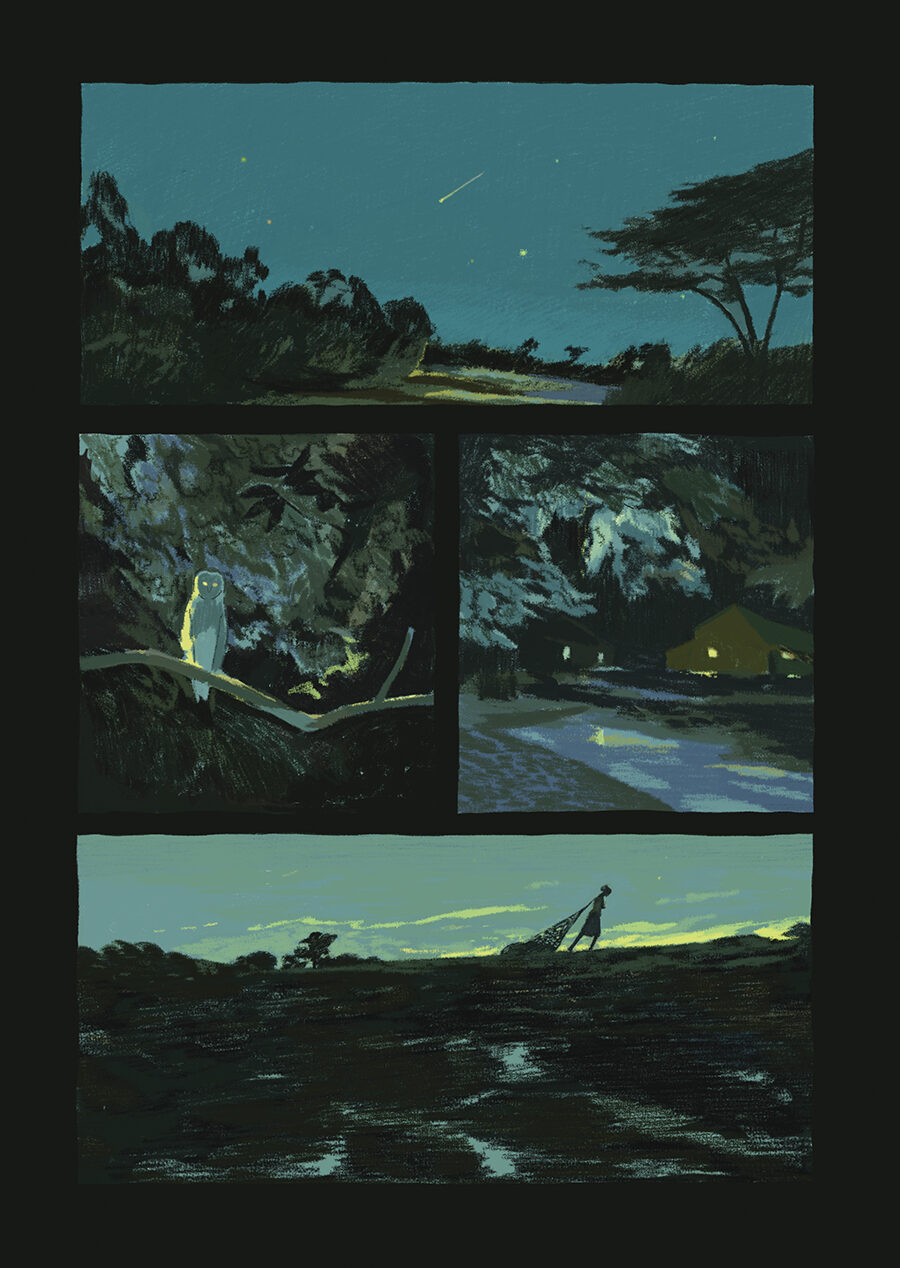

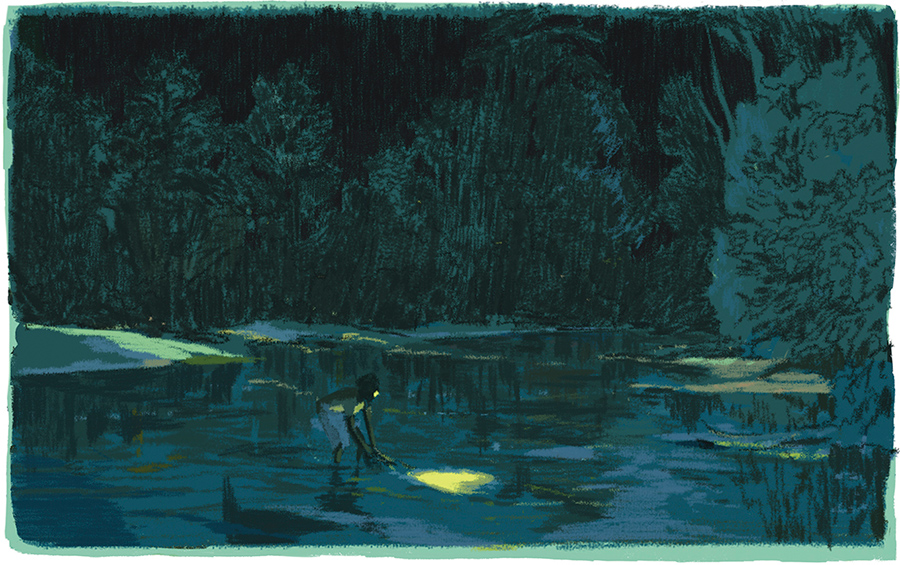

That night, I was slogging knee-deep in the steely waters, trawling for eels, flashlight taped onto my cap, fishing net dragging behind me, when I snagged on something large and heavy. I thought, Must be a coffer full of money. Must be that a robber flung it overboard from his dinghy and then hid it beneath the rocks.

I wrested my catch out, keeling over in the shallow murk, scraping my hands and bleeding them on the sharp rocks and the flotsam of the riverbank. In my head, I plotted how I would stuff the banknotes in a burlap sack and skip town on the very next train, with my hair still wet and plastered to my face, and with my teeth still grimy and unscrubbed, and with my fishing clothes still on my body—the musty overalls and jacket and galoshes that once belonged to my papa. I would not care at all what I looked like, as long as I made it onto that train. I would find a window seat and lean my head against the trembling glass, fogging it up with my sour breath, watching the dawn pinken and then tarnish and then turn to brass.

It was past 2 am, the moonless sky above black as the inside of a portmanteau. The flashlight on my cap was feeble, its shine whittled down to intermittent smears of butterscotch against the dark fabric of night. I wiped my brow, mouth half open. A bluebottle dove onto my tongue. I tasted that familiar bitterness of its waxy torso, and spat it out.

Now I bent over, and with both hands on the nylon fibers of the fishing net, I dragged it all the way out, across the rocks, across the tin houses where the townspeople snorted in fitful slumber, across the she-oaks and junipers and Cape chestnuts, toward my papa’s house. And all the while, as I trudged, I muttered and grunted. Glory be! to the rats and mongooses skittering at my feet. Glory be! to the feral cats snarling over fish bones in the gutter. Glory be, because it was a glorious occasion indeed—I would never have to make this trek again, to wade in the slime, to cast my net in the brackish water, to skulk about in the thick of night like a wayward ghoul. I would never have to haul eels in a wheelbarrow, to fry them at the marketplace, calling out, Two for ten shillings!

My papa’s house furled and unfurled, high as a church steeple in some parts, and low as a dung beetle in others. My papa had built it back when he still worked as an architect, before he’d lost his mind and started wandering the streets and sleeping in ditches. Still, the signs of his decline were there. You could see them in the spiral windows that were curled up in the walls, like giant stained-glass millipedes. In the doors that folded in and out of themselves, like accordions. In the shadows that gathered everywhere, as though at a plenary meeting, so that what you looked at was not always what you saw.The meadow of wild pansies scattered on the wallpaper? The Cabbage Patch dolls rocking back and forth in the farmhouse chairs? The old man in the corner smoking a pipe and poring over his newspaper? All those things were not real, only fragments of my papa’s noontime fever dreams.

I was feeling broody on account of the thing weighing heavy inside the fishing net. I suppose I was so convinced that I would find money in it, that I would finally get to leave the town, and this conviction brought me a sort of preemptive nostalgia. It got me missing my papa’s house before I had even left it. I filled a glass with ice water and nursed it slowly, thinking of the days gone by. Thinking of my papa.

He had named me Rosalie, after his sister, who died in infancy. My papa never told me that story, but I knew it well. Growing up, I heard it whispered all over town. I gathered snatches of it from the hair salon and the community hall, from the schoolyard and the post office, from the Coca-Cola kiosk and the posho mill.

The story was this: It had been storming one day, and my papa, who was fifteen at the time, had set out a tub to catch the rainwater. He did not see his infant sister—Rosalie—crawl out of her Moses basket, where she had been sucking on a blemished banana. He did not see her dunk herself headfirst into the tub. My papa found Rosalie like that, upside down, her little feet dangling out, as though she were not drowned at all but digging for worms or for a beloved rattle toy.

Naming me after the dead child was not an act of devotion as one might think, but rather an act of contrition. Each time my papa called out my name, he remembered what he had done in the old time, and he retreated acrimoniously unto himself. I had grown up hating my name for this—for the way it made my papa morose, full of old, undecayed hurt. For the way it stole him from the present moment and took him to his Rosalie.

My mama had left us when I was three. She could not stand my papa’s terrible moods. She could not bear to be his second wife. His first wife, she said, was Rosalie. My papa always whispered her name in his sleep, saying, Rosalie, I will give you an ice lolly if you come here and dance for me. If my papa was walking out in the street and he found a coin in the dirt, he would glance up at the sky and say, Hey, Rosalie, look what I got! One time, he and my mama were deep in the throes of passion, and my papa stiffened and shuddered and said, Lord have mercy, Rosalie! And my horrified mama hopped off the bed, and covered her nakedness, and jumped into her Toyota Corolla, never to return.

My mama sent me postcards each year at Easter. In them, she shared details about her brief marriage to my papa. About the ways in which he had failed her. About how she had tried to save him, and how, in the end, she had chosen to save herself. She said that his obsession with Rosalie always had the quality of a steamy affair. She warned me that my papa would never choose another woman over Rosalie, not even me, his own daughter.

To me, these details were both intriguing and repulsive. They reminded me of a time when I found a cow’s eyeball squished beneath my shoe on the way home from school, and the sight of it, all scrambled, was at once breathtaking and nauseating. The thing I always wanted to know, which my mama never shared in her postcards, was why she did not take me with her when she left. I suppose it was because I had that same name, Rosalie, and it offended her to no end. I suppose she would look at me and think of the way my papa often abandoned her so he could be with the other Rosalie. How, when he went away like that, he left behind a vacant shell of a man, one that stared blankly at the empty wall, with urine gathering in a pool beneath him.

I was ten when my papa completely lost his mind. He would be gone for days at a time, eating scraps that he wrangled from crows and rodents, and singing that cheeky song that got townspeople shrieking and covering their children’s ears. Johnnie’s middle leg is longer than the road to Kariokor. The townspeople said that he was mad as a cut-up boomslang. They broke off sticks and thrashed him, crying, Bugger off, you filthy prick.

And if he could remember the way, he would stagger on home, still laughing, his face raw from the thrashings, his hair full of dandelion or blackberry or milkweed. His spectacles askew, his clothes disheveled from days of wandering aimlessly through the streets. Eyes shining. Two warm beers swinging in his hand, one for him and one for me. Laughing, always laughing—at the dickey birds hopping in the tree branches, at the urchin who was burned to a crisp by an angry mob, at the slandering neighbor woman who got turned into a neighing donkey. And he would roar out, saying, Lord have mercy, Rosalie! Then his voice would grow soft, caressing the name. Oh, Rosalie! My Rosalie! Over and over, until he left himself and went off to be with her.

Absentmindedly, I had switched on the transistor radio. Now a voice, the poet’s, pulled me out of my thoughts. The poet said, Do you remember how blue tasted bent over the creek that swallowed Patricia of the thistles who fed her toes to the starving porcelain child? And red when we lay our heads down as the day grew tart?

The wind foraged through the eaves above, startling the little wild creatures that squatted under the roof, making them clamber up the rafters. Cane rats and pangolins. Barn owls and spotted wood snakes. The wind shrieked diabolically, rattling the window. I fastened it shut, and now I took out a penknife and knelt over the fishing net.

There was no coffer inside it, and no treasure either. It was just a woman, bundled up in an afghan of mohair wool. She was slight as a fernleaf. It was the weight of the afghan, its strands swollen with green river water, that made her heavy, that made catching her in the fishing net feel like catching something significant. In any case, she was dead, as far as I could see.

The woman’s eyes were pasted shut with what appeared to be wheat glue. She had thickets of buffel grass for eyebrows, a nose like a stick of penne pasta, and her mouth was hardly a mouth at all, more like a piece of string pulled taut near her chin. I jumped back in fright, toppling a chair. The wind cackled in the eaves, but the little wild creatures above were unfazed. They stood still, and I felt the weight of a dozen eyes watching me. Striped weasels and black tail scorpions. Rufous elephant shrews. All waiting to see what I would do next.

Tell the police? No, that would not do. See, they would burst in here, guns drawn, saying, You’ve got some of that madman blood in you, so don’t you act like you didn’t dead that poor woman yourself.

But maybe I could dig a hole out in the grove of jacarandas and casuarinas? Bury the woman inside it? This would require copious amounts of time and sweat to accomplish, but I had both in plenty, didn’t I? I bit my lip. No, that would not do either. The trouble with this plan was, simply, that the dead woman might not cooperate. She might swell up and burst into a swarm of weaverbirds or red-chested cuckoos, which would then howl and peck my eyes out.

I had heard of such things happening. You could not go burying people just fwa, without knowing who they were, meaning, if their mama was called Joyce Musanda Oketch, and if they’d had a hernia on their navel when they were younger, and if they spread Lady Gay lotion all over their body each night before bed. I thought, I’ve got to return her to the river.

I knelt down and began to work over the woman, tucking her feet together, wrapping the fibers of the fishing net over her, binding her tight. On the radio the poet said, I don’t have no soul swirling inside me like fog over boggy marshes just ask my mama she made me this way dogged beast that I am all bite but no bark.

And then, all of a sudden, something came, or something went away, and the room shuddered, the walls spasming, the light fluttering, but slightly, ever so slightly, so that I could not tell if I had only closed my eyes wrong and imagined it. Then I felt cold fingers stirring in my hands, and looked down to see the woman in the fishing net, not dead at all, and grinning like a horse, and chewing on a shred of something—string, or knotweed, or hair.

She said, Look at you, Rosalie Sincere Were!

I knew just who the woman in the fishing net was. It was the way she called out my name, as though she knew it as well as she knew the back of her own teeth. Called it as though she had both loathed it bitterly and loved it desperately for a long time. Called it just like my papa used to call it right before he grew morose and retreated acrimoniously unto himself.

She was the other Rosalie. My papa’s sister. Rosalie of the storm. Rosalie of the rainwater. Rosalie of the little feet dangling out. All grown up now. She was what, thirty-five? She coughed out green water, and choked, and spat out a whole crayfish with twitching legs and quivering antennae. Would you please give me a hand? she said to me.

I freed her from the fishing net and carried her out onto the wicker sofa. I brought her a tray of orange juice and saltines, and watched her lunge at it. I brought more food out—a bunch of bananas, five hard-boiled eggs, a loaf of bread, pumpkin soup, broiled brisket. Rosalie ate everything in no time at all, stuffing her throat as though she were a python.

Now, with her energy restored, she lifted herself up from the sofa. She walked about, touching things—the architecture and design books on the bamboo shelf, the soapstone figurines, the framed portraits on the wall, the wine crate filled with vinyl records. I watched all this, thin-lipped. Finally, I grabbed my fishing net and let myself out into the frosty daybreak. I thought, Surely, Rosalie will be gone by the time I return with a fresh batch of eels to gut.

I waded into the water, stomping furiously, startling the snipes, making them shriek, Hleep! Hleep! as they fled from me. I was angry at my own naïveté, at my catching something hefty in my net and then immediately thinking, with utterly no right to do so, that things would be different. Thinking that I could finally leave this place.

Eel catching had been my papa’s hobby. He would spend weekends in the river, watching the baited cages that he had built from wire. He had sophisticated equipment—seines, longlines, fyke nets, fishing spears. In the evenings, while stirring a pot of eel soup, he would talk animatedly, telling me all sorts of facts about eels. The difference in flavor between the ones you caught in the mud and swamps, and the ones you caught in the estuaries. The rivers and lakes that one ought to avoid because of toxic mold. The arduous journey that the female eels had to make, for thousands of miles, back to the ocean to spawn.

I had become an eel catcher when my papa started to wander the streets and sleep in ditches. I needed the money—to feed myself and to feed my papa too whenever he returned home. So I trawled, and I dumped the eels in a wheelbarrow and fried them at the marketplace. Now fifteen years had gone by, and I was still at it. I abhorred eels—their slippery bodies writhing every which way, their slime that you had to salt and then rigorously wash off, and the smell of their guts, how it clung to me at all times, so that bluebottles followed me everywhere I went.

Rosalie was still there when I returned home from the river. It looked like she had made herself at home in my papa’s house. She had moved things around to her taste—the wicker sofa so that it faced the window, the potted plants so that they were closer to the light, the bamboo bookshelf so that it was beneath the sloping wall.

Rosalie had done other things too—cut the grass that had been so tall it had gone up to my chin; and smoked out the wasps that had lived on the kitchen ceiling; and plucked the mangoes steaming and festering in the tree in the yard, and then made jam and chutney with them. She had scrubbed the floors and made them glint. She had filled the cracks in the wall with cement and then painted them over. She had cooked up a feast, and now she set the table out in the sun. We sat under the surging sky and the trilling birds, with the soft breeze nuzzling our necks, and we ate brunch as though we were the type of women who wore pinafores and pantyhose and played footsie underneath ivory tables.

I let Rosalie stay there with me in my papa’s house. It was rather nice to have someone waiting at home for me like that, with red lipstick slathered on, and with warm biscuits on a platter, and with Miriam Makeba singing “Pata Pata” on the radio cassette player. We hardly said a thing to each other, beyond “good morning” and “thank you for cooking” and “good luck with the fishing today.” Yet there was nothing strained at all about our silences. They were as tender as moth wings, and as wholesome as a field of wheat. We brushed fingers as we passed each other glasses of wine, and we giggled with our eyes and our mouths, and we told each other secrets just by gazing at each other, without speaking a single word.

She knew, for example, that my mama had sent me a postcard when my papa died, that she had stapled to it a bus ticket for me to go see her, and that I had not. She knew that I was saving up money, hoping to one day get on the train and leave this wretched, waterlogged scrap of nowhere.

And I knew that she had crossed the threshold often through the years, coming out of the ground and walking past our house just to peek at my papa and me eating eels at the kitchen table. I knew that once, she came to us as a housemaid called Rehema, working in our house, scouring our dirty clothes between her palms, starching them and ironing them. Loving my papa in fierce but revering quiet.

Rosalie loved the rain that stung like nettles, and she loved all the yellow things that she could find—caramel toffees, and egg yolks, and honeycombs, and Lucozade, and rubber ducks. She was like an ordinary woman in every way, except that her skin was fine as the inside of a seashell, and that her voice box was located in her belly. This latter fact meant that sometimes, while humming to herself, the song in her throat dried up and she had to wind it out again by pressing beneath her rib cage.

One day, I went out to the river as usual. I caught something heavy, much heavier than Rosalie had been when I dragged her out in the fishing net. I tugged and tugged and tugged, and the thing in my net would not budge.

Wait! someone yelled.

I looked up, and saw that Rosalie was at the riverbank, jumping down from the driver’s seat of a green Canter truck. She was barefoot, dressed in a silk camisole. Her coarse hair, which was dyed yellow, rolled about in the wind like a bush of dried barley. She launched herself into the river, losing her balance and falling, picking herself up again. She made her way to me and grabbed one end of the fishing net. She screeched with excitement as we sloshed out onto the rocks.

I had caught an astounding quantity of longfin eels, each over a meter long, and weighing in excess of five kilos. I knew that it was Rosalie that had done all this—summoned to me such a rich and burly catch. Later, as we drove back home to gut, I asked, Whose truck is this?

I had a lover once, Rosalie said. He gave me a diamond ring. This morning I walked to the car dealership and offered the ring to them, in exchange for the truck.

Now Rosalie looked out the side mirror, and she frowned at the sight of black smoke rising behind us. She said, It’s not the most elegant thing, but it runs, doesn’t it?

After that day, Rosalie began to accompany me to the river. Each morning, we awoke at 4 am, put on our fishing clothes, and drove out to the water. Always, we caught a lavish number of eels, and stuffed them into the bed of the truck. When the sun rose, we returned home and drank sweet black tea and ate yellow scones, and we salted and gutted the eels, and then we left for the marketplace, where I hunched over and fried while Rosalie called out to the townspeople, saying, You over there with the sorry face, I’ve got just the right cure for your ugliness.

Six months of this, and Rosalie and I had made a pretty penny together. I counted it all, and saw that even after giving Rosalie her half of it, there would still be enough left for me to finally put my eel-catching days behind me. When I told Rosalie this, she leapt out of her chair, where she had been shelling peas, and threw her arms around me, so hard that we both fell laughing to the floor. Then her laughter turned to wet, snotty, red-eyed sobbing.

Happy tears, she said, sweeping up the peas that she had spilled all over the floor. She got up, grabbed our coats and umbrellas, and started for the door. Come with me, she said. I’ve got to show you something.

We walked through the woods, leaping over the stumps of stinkwood trees that had been illegally felled for timber and charcoal, leaping over the decaying corpses of Meru oak trees that had been struck by lightning, leaping over mud puddles too, with the deafening shriek of the daytime crickets in our ears, and with flying foxes thwacking our faces, and the bluebottles—the deplorable bluebottles—chasing after us because they could smell the eel slime trapped underneath our fingernails.

She was still crying, which perplexed me, so I asked, What is it, Rosalie?

She stopped walking just long enough to use the wind as a handkerchief, blowing her nose into the air beside her. She said, You and me, we have a good life together. But it can’t continue—I’ve got to leave you.

Why? I said.

Your papa can’t bear to be without me much longer.

My papa?

Rosalie nodded. She said, I can’t sleep anymore. Every night, I hear his cries inside the ground, saying, Lord have mercy, Rosalie, you’ve got to come back to me. Oh, my word, he sounds so tortured! If only you could hear him, too, your heart would be crushed.

I did not know what to say to this. All I could think of was my mama saying that my papa would never choose another woman over Rosalie—not even me, his own daughter. Back then, I had thought that my mama was only a bitter, jilted woman, that she spoke out of turn. And I had resented her for it. Yet, now I saw just what my mama had meant. I saw, also, that Rosalie was exactly like that. That she could never love anyone but my papa. I felt foolish for ever thinking otherwise—that our golden days would stretch on forever, that she would leave this town with me, go to someplace new, where we would get jobs as secretaries, and spend our evenings drinking bone soup and watching Ousmane Sembène films.

Please, I’ve got to go back to him, Rosalie said, as though I had said anything to forbid it. She turned, and cupping my face gently with her hands, she murmured, You understand, don’t you?

I understood nothing, except that I wanted nothing to do with a love like that. A love like theirs.

We heard twigs snapping. Rosalie’s eyes widened. Look, she whispered.

We watched as a dik-dik crept over the rotting foliage. It sensed our presence nearby and raised its head to appraise the danger that we posed.

Shh, Rosalie whispered. Dik-diks scare easy. Let’s not scare him.

Is that what you wanted to show me? I asked, my throat wriggling with the weight of a thousand millstones. I was fighting back tears.

No, Rosalie whispered. That’s not it.

The dik-dik went away, and we continued walking.

It’s not normal, Rosalie said. The way you live. Out in the middle of the woods, all alone.

My papa was the one that did it. Moved me away from the town like that.

Give him some grace, he wasn’t himself.

I shrugged. And I said, Why did you come out of the ground that night I caught you?

Matter of fact, I came out of the ground a few weeks prior to that, she said. I came by your papa’s house and peeked in your window often to see how you were doing. And I saw how sad you lived—eating bland French beans out of cans, never opening the windows or drapes, and hiding in the shadows, pretending no one was there if a visitor came knocking on the door. I didn’t mean to get caught in your fishing net at all. I was only having a midnight swim. But then you brought me home and I thought I should stay just a little while to cheer you up.

We were standing outside Dominatrix Discotheque. I leaned against the flowerpots on the ledge, my back pressed to the pane. I stared at Rosalie—her pebble-shaped face, her eyes that gleamed like china saucers, her jawline that was sharp as a butcher knife. I wish you hadn’t stayed, I said. I wish you had left me alone.

I only wanted to make sure that you were all right.

All right? I said, my voice high-pitched, incredulous. My papa chose you over me. He threw himself at death just so he would go in the ground with you. What do you think?

Rosalie lowered her head sorrowfully. She said, He talks about you often, if it’s any consolation.

I shook my head. No, I said. It’s not.

Rosalie wiped the wetness of her eyes with the back of one wrist. She said, I needed to make sure you were all right. I helped you save up the money, and now you’ve got a truck too. You can go anywhere you like, start afresh. Isn’t that what you always wanted?

Piss off, Rosalie! I yelled. I ran my hands through my tresses, and then buried my head in my palms. After a long moment, my rage passed, and I opened my eyes again. I looked into the window of the discotheque. I saw women in spangled gowns and kitten heels patting each other’s gold-trimmed coiffures. A serving girl tipped sparkling drink into flutes. Women slipped arms round each other’s waists and swayed to the trembling falsetto.

This is what you wanted to show me? I said.

The other Rosalie said nothing.

Rosalie? I said, searching about me.

She’s gone, someone said, startling me. The woman you were talking to, she’s gone.

I turned away from the window, my hands jerking, upsetting a pot of angel-wing begonias. I righted the pot, gathered the dirt and put it back. There was a woman behind me, her arms covered in satin gloves so long they went all the way to her armpits. Her hair and eyes and lips and teeth all shimmered. Her skin shone amber, as though a hurricane lamp flickered inside her.

Rosalie Sincere Were! You came out to see me? You came to see your mama?

My head reeled. So this was what the other Rosalie had planned all along—to reconcile me with my mama? The woman before me was saying, Rosalie, I’m on tour with the jazz band, and our manager decided we ought to perform in this town tonight. I was hoping terribly, hoping against hope really, that you would come out and see me. How did you know to come?

I lowered my head. Here I was, gangly, almost twenty-six, already gray at the temples, and raw on the knuckles, my fingertips charred, callused, my body full of strange, rattling objects. I smelled of eels the way other women smelled of jasmine or lavender. I knew the river and the sorrels and the bad-smell melons. I knew the brush-footed butterflies and the nightjars and the bush babies. What did I know about being some jazz musician’s daughter?

Rosalie? my mama said. I’ve got to go onstage. Please stay and watch me sing. Later, we’ll have a drink together, and I will tell you a story about when you were little, how you always grabbed the mice that the cat brought in. How you chewed their mangled heads and spat them out like sugarcane dregs.