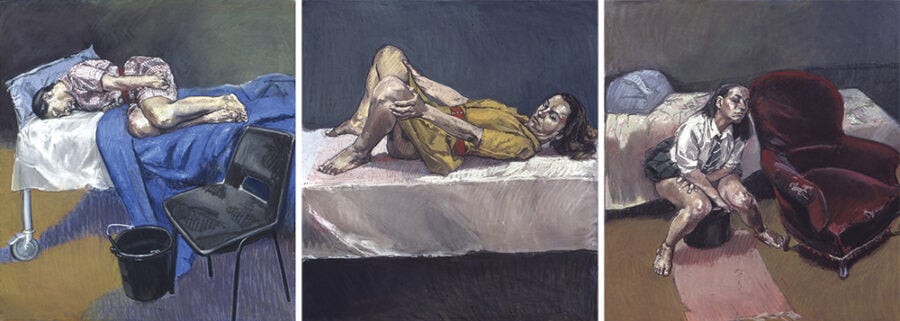

Triptych, 1998, by Paula Rego, from her Abortion series. Courtesy the artist; Victoria Miro, London; and the Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Lakeland Arts, Kendal, England

I’ve never wanted to be pregnant, and I’ve been pregnant three times. Each time I learned the news, my commitment to what I’d already known was confirmed viscerally and instantaneously—with the unshakable certainty of no. I say “no” often. I think “no” frequently. I am no stranger to “no.” But this refusal lived at a different depth. It saturated me. It constituted me like my lungs and my limbs and my mind. No, I do not want to be pregnant, I do not want to give birth, I do not want to have children. I wasn’t choosing because there was no choice. I didn’t want to be pregnant. No.

My experiences were too common to be remarkable. Nearly half of the world’s pregnancies are unintended—more than 120 million inadvertent conceptions per year, almost three per second. The ability to conceive is an inherited state of being and is not synonymous with the desire to do so. There has never been a time when this wasn’t true, and there probably never will be. But people capable of pregnancy have options to manage and react to their bodies’ potential. Biology need not be destiny.

There is no process equivalent to pregnancy. Its ubiquity as a mammalian fact, its inexorable repetition across species, places it among other involuntary courses of the body, such as respiration, digestion, and cellular deterioration, but it is unlike anything else. Over the years, I’ve heard pro-choice advocates suggest that abortion restrictions are akin to laws that would force people to donate their spare kidneys, or host parasites, or, farther afield, save strangers from drowning—to in some way use and risk their bodies in service of another. But these theoretical burdens do not come close to approximating pregnancy’s protracted invasion, debilitation, and deadly hazard.

Neither do they capture the extent to which that hazard is constructed by one’s own body. Anti-abortion agitators often use sonogram images to push the fiction that women are merely incubators for a self-sufficient process—that pregnancies happen in women and are connected to them by only temporary, inconvenient placement; that a zygote, then embryo, then fetus, is in some sense independent, complete from the moment sperm meets egg, or built by God alone. Each of my pregnancies was confirmed early, before I had recognizable symptoms; one was discovered so close to conception that a vaginal ultrasound turned up no visual evidence. I received knowledge about my body from the outside, which made what was set in motion abstract but still too real: the me of myself slammed into my body, as if my consciousness were a nail hammered into place, my fate pinned to a process that would colonize me if left unchecked. My pregnancies were not separate from me—they were not in me but of me. My physical form marked where the phenomenon began and ended. The growth would be impossible without my organic matter; nothing about it occurred without incorporating the material of me. That reality left no doubt that the predicament was exclusively mine. Regardless of any government document, religious stricture, or rarefied morality, the knowledge that I was pregnant came with the understanding that I had the right not to be.

The right to not be pregnant ought to be at the core of reproductive freedom, yet the United States has never legally recognized this right, and no mass movement of its citizens has ever expressly demanded it. Though Roe v. Wade has long been regarded as a feminist gold standard, it did not establish an individual’s unconditional right to end their pregnancy. The ruling granted that the decision to abort was protected by the right to privacy implicit in the Constitution, but it placed that decision explicitly in the hands of doctors. In the words of Justice Harry Blackmun, in the majority opinion, abortion is “inherently, and primarily, a medical decision,” and therefore the “basic responsibility” for its use “must rest with the physician.” The procedure was thus under the purview of a credentialed, impartial authority, referred to in the common masculine possessive: “The attending physician, in consultation with his patient, is free to determine, without regulation by the State, that, in his medical judgment, the patient’s pregnancy should be terminated.” The idea that a “woman’s right [to abortion] is absolute” was deemed “unpersuasive” and directly rejected. In closing, Blackmun affirmed the rights of the state—declaring that it maintained the right to regulate “potential life”—and reaffirmed those of the physician. The government held on to the master keys and lent a pair to the medical establishment.

Leaving the adjudication of abortion to doctors was no more just than leaving it to legislators. It was in fact male physicians, in the mid-nineteenth century, who first campaigned to criminalize the procedure across the United States. This movement served at once to legitimize their nascent guild—casting them as uniquely educated, moral actors—and to eliminate their competition: the midwives and folk healers who had provided abortions since the beginning of human society. While Roe was in effect, many hospitals—not only Catholic and Protestant but secular and public as well—denied pregnant women abortions and miscarriage treatments that were permitted under the law. A 2021 Columbia Law School report concluded that such refusals made abortion access “even more severely curtailed than already-restrictive state laws suggest.”

Though the Supreme Court revisited the right to abortion many times in the half-century between Roe and its reversal, the role of doctors remained unchanged, and a pregnant person’s full bodily autonomy was never established. Yet mainstream abortion-rights advocates maintained a myopic, reactive fixation on the language and frameworks employed by the state and by their opponents. The abstract rights “to privacy” and “to choose”—the latter mantle taken up in the late Sixties in direct response to the ascent of “pro-life” propaganda—are the rights most associated with abortion in the broad culture. The right to privacy is vague and easily rejected when balanced against a greater right or potential harm, particularly when positioned against supposed murder. The right to choose, though a valuable recognition of a pregnant person’s agency, is so euphemistic that it has been neatly co-opted by anti-vaccine and anti-mask crusaders, many of whom oppose abortion.

The failure of this rhetoric is all around us—not simply in the fall of Roe but in the persistent degradation of abortion access over decades prior, and in the increasingly cruel criminalization of abortion and other events of pregnancy. From now on, we who fight for reproductive freedom must announce our cause in the clearest terms: every impregnatable person has the right to not be pregnant.

It is critical to understand that the “pro-life” movement is much more than an anti-abortion cause: it is a pro-pregnancy crusade, pushing for pregnancies to be maintained at any cost. As of this writing, seven states have banned abortion without exemptions for rape and incest, previously a nonpartisan standard of decency. Conservative states are well into the process of winnowing down special dispensations for the “health of the mother”: some by changing the criteria for exemption to a probability of death; or, as Ohio and Tennessee’s new laws, prepared years ago and instituted in June, generously allow, “substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function.” Whether a pregnancy meets these indeterminate, immeasurable standards will be assessed by doctors at risk of civil and criminal charges for any suspected failure to sufficiently prioritize the fetus.

After years of right-wing insistence that women would never be criminally prosecuted for seeking abortions, legislation is now being introduced that would allow them to be charged directly. Though later amended, in May, a bill was advanced in the Louisiana statehouse that sought to make all abortion, at any stage, murder. In the thirty-eight states that have already established “fetal homicide” laws, those who obtain abortions can currently be charged with homicide and manslaughter. As the New York Times reported in early July, in certain states, women who abort may be eligible for the death penalty. One pastor told the Times that execution would indeed be a fair penalty for abortion, though he didn’t trust the state to deliver it.

Those who seek to criminalize abortion do so with the orientation of a simple, chilling vision: that those who can be pregnant should be, and will be conscripted into sustaining pregnancies regardless of their own desires. Pregnancy prevention tools have always been next in the line of fire. For over a decade, conservative lawmakers and “conscientiously objecting” pharmacists have, without proof, described these contraceptive tools, which prevent egg fertilization, as methods that instead block the implantation of embryos. This lie previously provided spotty cover for the fact that lawmakers or their bankrollers wished to bar contraception itself. In May, the Mississippi governor Tate Reeves, during a CNN interview in which he defended forced pregnancy for incest victims, refused to rule out a state ban on contraceptives. This is at root a desire for state control over all aspects of pregnancies: when they happen, whether they happen, and how they progress—a fundamentally fascist aim.

Though plastered in sentimental language about the sanctity of life, the heart of the anti-abortion coalition is revealed in full by its insistence that a pregnant person’s integrity, including their health, is tangential at best and a frivolous, unjust obstacle to a fetus at worst. This conceit is crucial for legitimizing the aims of the natalist state. It is monstrous to refuse a “child” life, they say, and objections based on the tremendous burdens, sacrifices, and risks that this potential life poses to a living human being are ignored and denied, with pregnancy described as no more than a brief inconvenience. The Supreme Court justice Amy Coney Barrett exhibited this view in December when she theorized from the bench that abortion’s legal necessity may be negated by the existence of nonpunitive adoption opportunities, blithely describing denial of a later-term abortion as “the state requiring the woman to go fifteen, sixteen weeks more.” Under this characterization, for a woman to resist her pregnancy is to be grotesquely selfish, perhaps murderous.

Anti-abortionists’ mounting refusal to acknowledge circumstances in which abortions keep people alive has shocked the general public in recent months. But this denial is consonant with their long-standing ambitions, and propped up by a depiction of pregnant people as invulnerable incubators, unaffected by the lives they house. “We don’t think abortion is ever necessary to save the life of the mother,” a director of Pro-Life Wisconsin, a lobbying group, told the Washington Post in May, a statement that can only be understood within the reality the movement has drawn for itself: one in which it is unnecessary to save the mother, full stop. The “life of the mother”—language that elevates a pregnant person’s role in birthing over their humanity—was never the right’s priority. Impregnatable people, in the right-wing conception, constitute a distinct, female, and subhuman class: a resource that requires domination due to the value of what can be extracted. The pregnancy matters; the pregnant person does not. Coding all impregnatable people as women is also essential to the right-wing project: enforcement of gender and bioessentialism do a great deal for social control. As with transphobic legislation, the effective result is to alienate people from their own bodies and thus their own lives.

Because the anti-abortion orientation is toward control—not life—the cosmology does not admit the possibility of a non-viable pregnancy. As the fetus is valued over the pregnant person, the phenomenon of pregnancy is valued over the fetus. Notoriously, in 2019, Ohio attempted to pass a bill for cases of ectopic pregnancy—a life-threatening condition in which a fertilized egg has implanted outside of the uterus—which would have required that doctors “reimplant” the embryo. This is, to borrow the words of the Cleveland Clinic at the time, a medical impossibility. The American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists—doctors who apparently wish to hold anti-abortion positions without seeming to prescribe killing pregnant people—describe the intervention in ectopic pregnancy as a “treatment,” and not an abortion. This semantic maneuver may or may not be intended to permit the procedures to take place, but it certainly allows the group, and anti-abortion advocacy organizations, such as the Life Institute, to claim that bans on abortion never prevent care for ectopic pregnancy—a demonstrable lie. In the days after the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe, some doctors began refusing to prescribe methotrexate—a drug used to treat arthritis and employed in chemotherapy—because it is also often used to end ectopic pregnancies. The Life Institute asserts that there have been “many reports of successful ectopic pregnancies,” citing a doctor’s claim, from 1917, that he reimplanted one as “documentation” of what must now be possible with advanced medicine. The organization goes on to suggest that a woman’s positive attitude in the matter can be her saving grace.

To call the anti-abortion cause a “forced birth” movement is too kind, and misses these extremists’ ultimate objective: dominion over impregnatable people. Their preoccupation with fetuses is useful only inasmuch as it facilitates this aim. Why else would they ensure, under pains of criminal law, that pregnant people suffer and die when their sacrifice cannot produce a living child?

Forced-reproduction legislation is part of a network of laws that police pregnancy broadly. For decades, under cover of prosecuting “fetal endangerment,” the state has surveilled, arrested, and incarcerated black and poor women especially for the events and accidents of their independent lives: Pregnant women have been charged with first-degree murder for attempting suicide; in 2019 a pregnant woman in Alabama was charged with manslaughter after someone shot her in the stomach. Those who have miscarried or experienced stillbirth have been prosecuted for a wide variety of crimes, including homicide, and pregnant people are regularly jailed for behaviors that are not illegal in and of themselves, such as having HIV. The criminalization of living while pregnant has resulted, as documented by the scholar Michele Goodwin in Policing the Womb, in women giving birth “while shackled in leg irons, in solitary confinement, and even delivering in prison toilets.”

After years of paying lip service to the sanctified figure of the pregnant mother, as these horrors played out behind courtroom and penitentiary doors, anti-abortion forces are openly declaring their desire to punish non-compliant pregnant people. The National Right to Life, the self-proclaimed oldest and largest “pro-life” organization in the country, recently released a proposal for state-level legislation in post-Roe America, in which the group preemptively decries any “Democratic prosecutors” who may be reluctant to jail people for procuring abortions, and recommends that anyone who attempts an abortion, regardless of its success, be charged with a felony. In May, two men writing for the popular evangelical website The Stream warned that “maternal sovereignty”—the “right to refuse motherhood”—is so dangerous and “deadly” a notion that “rational women” who abort “for calculated reasons” should be placed in “short but mandatory psychiatric custody.”

The crime here is the pregnant person’s will, their very personhood—the animus of an individual’s spirit. In a world dominated by the anti-abortion right, people who are capable of becoming pregnant and opt not to do so mark themselves as dangerously antisocial, and must be dealt with accordingly. Centuries of law, medical protocol, and popular beliefs have laid the groundwork for this conception, seeding the broader culture.

Policies that conscript people into pregnancy may seem contrary to regulations that have subjected black, indigenous, disabled, and poor Americans to forced or coercive sterilization and the removal of children from birth parents—regulations that have worked to refine white supremacist power. But as the sociologist and legal scholar Dorothy E. Roberts has explained, a program need not be geared toward “physical annihilation” to inflict oppressive and catastrophic harm: “Reproductive liberty is vital to our human dignity.”

In the face of the right’s unremitting fascistic efforts, the Democratic Party has faltered continually, moving between denial, evasion, and concession—weakened by their own trace natalist beliefs, cowardice, and the delusion that their opposition would somehow be appeased. Tragically, reproductive-rights advocacy groups, operating within the same political machine, have mirrored their supposed allies’ suppliant stance, and members of the general public who support abortion rights have been abandoned to the unforgivably self-defeating slogan of “safe, legal, and rare” and the polite-company taboo—accommodated by “my body, my choice”—against even uttering the word “abortion.” In the same spirit of concession, ostensibly pro-choice leaders have long maintained that abortion isn’t, or shouldn’t be, birth control, drawing a hard line between the two as agents of greater and lesser harm, attempting to shore up the definite morality of the latter. Implicitly playing along with the contention that abortion—sometimes, in some cases—is murder has helped pave the way for the conservative movement to force victims of rape and incest, including children, to carry pregnancies to term. There could be no other conclusion: very few would argue that a violated person is allowed to “take an innocent life.”

As Republicans make known their conviction that women, by definition, should be pregnant, and therefore can be forced to be, Democrats and the broader liberal apparatus respond that women want to be pregnant, insisting that people have abortions because they aren’t able to be pregnant right now: they intend to conceive in the future, after they’ve finished college, or escaped a violent relationship, or found a higher paying job; or their pregnancy isn’t viable but they’re determined to try again; or they’ve been pregnant before and are already raising children. Women who have abortions are no longer expected to be broken by grief, and there’s now more room to admit relief, but that’s often coupled with the reassurance that their childbearing duty will be, or has been, fulfilled. Those who have multiple abortions uninterrupted by giving birth, who are child-free regardless of resources, and who refuse to justify or explain their terminations, remain insufficiently sympathetic to warrant inclusion in the liberal narrative, which implies that the principle at stake—bodily autonomy for everyone, an inherent and internationally recognized human right—is negotiable and conditional. Likewise, stories of unwanted but necessary abortions—harrowing and heartbreaking as they are—are degraded as chips in the liberal bargain.

The right to not be pregnant is a concept of autonomy that goes beyond the reactive and reparative. It lays claim to a state of being, not an action, and in doing so obviates arguments about what abortion is or is not (health care, violence) and who or what is entitled to influence a pregnancy’s course (the fetus, the government, the doctor, the family, the provisioner of sperm). Critically, the right to not be pregnant rebukes the notion of non-pregnancy as a luxury or a sin, a widespread, inherently misogynistic idea tacitly conceded by the liberal mainstream.

There is no anti-abortion legislation, not even the third-trimester abortion restrictions masquerading as the reasonable person’s limit, that is compatible with the full personhood of pregnant people. Democrats concerned with public opinion nervously note that late-term abortions are rare and almost exclusively performed because of unexpected medical complications. This is true but beside the point. If any circumstance of a pregnancy forfeits a pregnant person’s autonomy, their pregnancy has reduced them to an object, an instrument, less than human, and they will be used this way by the state.

To designate good and bad, earned and undeserved, permitted and forbidden abortions is a foul and foolish tactic that ends in denying people their rights to themselves. The pro-choice narrative comes at an extraordinarily high price—confirming that people capable of pregnancy exist to create more people—for no reward. Liberal haggling has achieved only self-sabotage. And it has prevented abortion advocates from matching the intensity and focus of our foes. It is time to meet absolutism with absolutism: Every person has the right to not be pregnant.