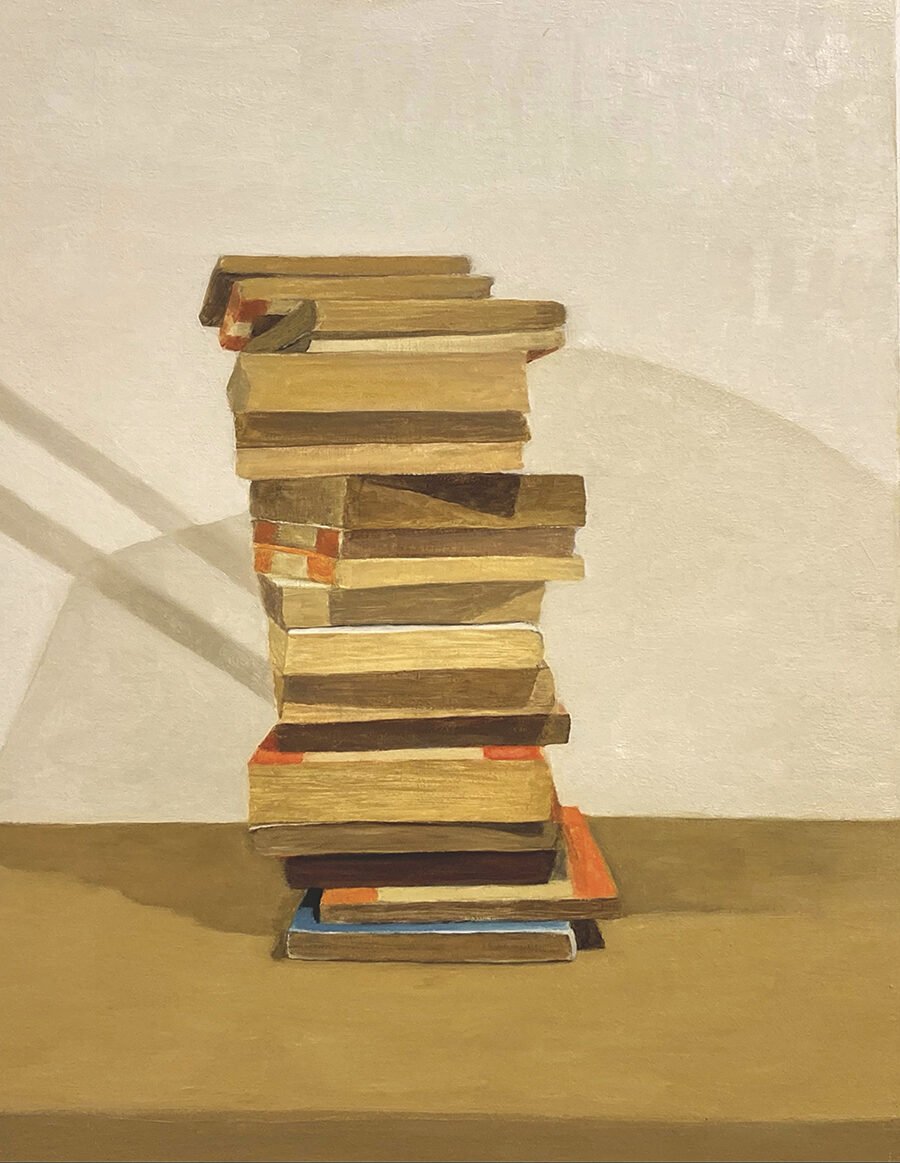

The Books in the Spare Room, by Jess Allen, whose work will be on view next month at Scroll, in New York City. All artwork © The artist

For three weeks, we sat in a windowless room and listened to people talk about books. Most of the time we didn’t know the titles or authors. Instead we heard about money. We heard about advances, royalties, and option clauses. We heard about foreign rights, world rights, e-book rights, and audio rights. We heard about auctions for manuscripts in all their varieties: round-robins, best bids, better/bests. We heard about preempts and bilateral negotiations. We heard about profit and loss projections, marketing budgets, and distribution. We heard about visibility in bookstores and discoverability via algorithms—all the transactions that make reading possible.

We heard that the U.S. market for books had increased by 20 percent in the prior two years: “It was like a hockey stick during COVID. The industry is thriving.” We heard about books as “projects,” meant “to create something that has inherent value for the culture,” or “to become a nondeniable proposition in the mind of the editor,” or “something that’s so exciting, or so important to the political culture, or so moving, that they call me and they say: I have to have this. What do I have to pay for it?” We heard that “there’s a tremendous wealth of intellectual property in books.”

We heard that an “unreliable narrator” was “what readers were craving”; that “psychological suspense” is “very big”; that “historical fiction is red hot”; that “sexy vampires” can yield a “franchise author”; that “it’s very hard to make a success out of short stories”; and that it’s “very difficult to create success out of whole cloth just through marketing.” We heard that “social media is having a big impact on the business.” We heard about BookTok influencers. We heard that “you can’t control” TikTok because “it needs to happen on its own, naturally.” We heard that a “celebrity-adjacent author” with a “platform” can be as good, or better, than a genuine celebrity. We heard that publishers give some authors “glam budgets” because “if fans are used to seeing these . . . authors on TV, we need to make sure they look the same in real life,” but that “you don’t ever talk about glam with fiction, really.” We heard that “if you write science fiction, there’s this endless list of sci-fi conventions you can go to. And you get paid to do that.” We heard that “Hollywood buys the rights to all these books, even if they’re not going to make them into a movie. And they pay really well.” We heard that “word of mouth is the most electric, galvanizing aspect of why people read and buy books. So we put it out there, and then whatever happens happens.”

We heard that “it’s a business of passion.” We heard that “it’s a business of gambling.” We heard that “a lot of the books don’t succeed.” We heard that “when you fail, everybody feels it.” We heard that it takes about two thousand hours of labor to bring a book to market, or “about the same amount of time as authors may spend creating their work.” We heard that an “editor is sort of like the orchestra leader.” We heard that “often it can be the difference of two or three books [that] totally changes the financial performance of the company.”

We heard that “the goal of being a writer is to write something that is beautiful and true that people want to read and to figure out how to inform people that this book exists.” We heard that “you can’t underestimate the impact of a prospective author thinking they could be published by the same house that published Mark Twain.” We heard that “selling the most books is both spiritually rewarding and financially rewarding.” We heard that writers are “trying to communicate something. And the editor who can help them bring—make the richest, most robust project, that means the world to them.” We heard that “a writer can write something that’s good, but the best a writer can do is good. To be great, you really need an editor who makes it great.” We heard that “most writers will say that, outside of their marriage, their closest and most intimate relationship is with their editor.”

We heard that “the book is the greatest creation of humankind and people who write books are incredibly admirable, often heroic.” We heard a publisher who was asked, “What is literary fiction?” respond, “Not commercial. Might win a prize.” We heard that “the real money” comes from “selling a lot of books.”

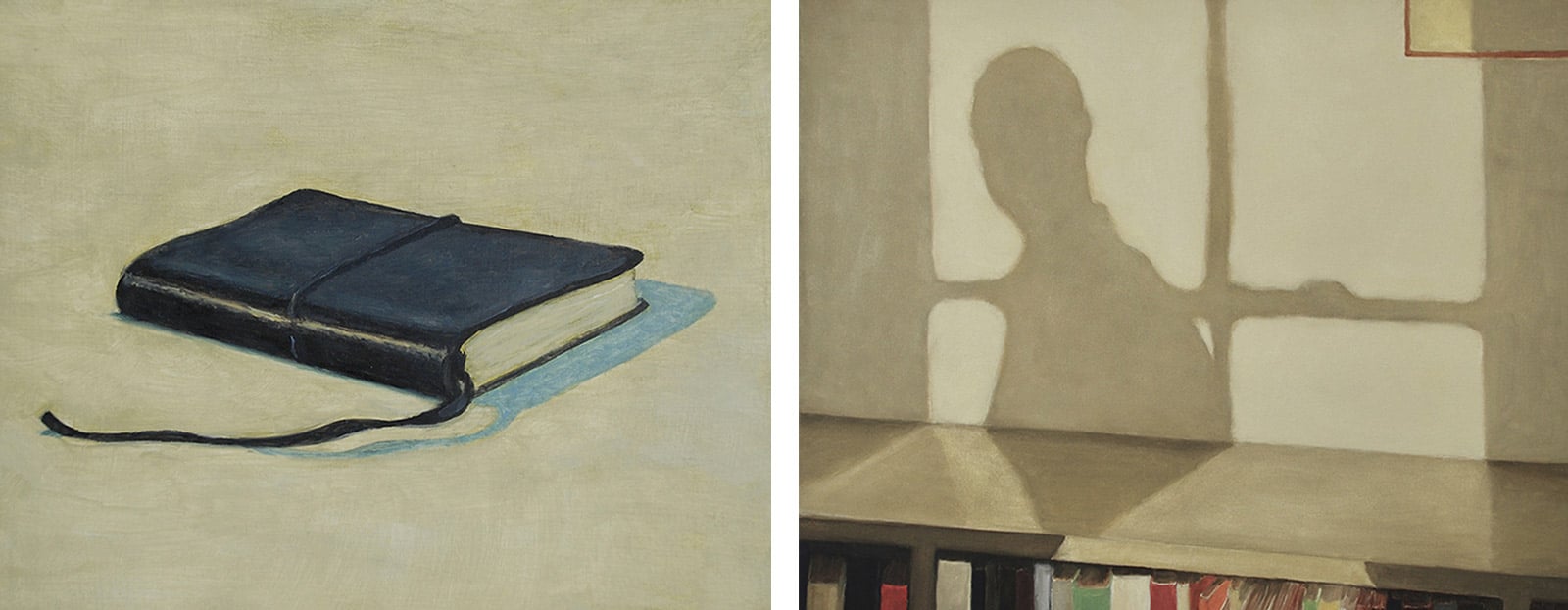

His Little Black Book, Study 2 and The Shadow Man, Study 7, by Jess Allen

In March 2020, ViacomCBS announced its intention to sell the book publisher Simon & Schuster, long a CBS property, because it did not fit the recently merged company’s new business model, which centered on streaming video. That November, Bertelsmann—the privately held German owner of the largest publisher in the United States, Penguin Random House—entered a $2 billion deal to purchase S&S. And in November 2021, the Department of Justice’s antitrust division filed a civil lawsuit to block the merger of the two publishers.

In 2013, the Obama Administration had declined to challenge the merger of Penguin and Random House, then the country’s two biggest publishers. But the Biden White House has promised a more aggressive approach to antitrust policy. On August 1, 2022, Judge Florence Y. Pan of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia began hearing United States v. Bertelsmann, et al.

In the popular imagination, antitrust cases are taken up by the government on behalf of consumers, and this has, in fact, been the general approach for several generations. But the Justice Department lawyer John Read specified in his opening argument that consumers of books—also known as readers—were not the harmed party in this case. These consumers constitute the “downstream” market for publishers as sellers, the primary “upstream” market for publishers as buyers was the rights to manuscripts. The government’s case was thus a defense against monopsony, being pursued on behalf of producers of manuscripts—also known as authors. And not merely authors generally, but authors of “anticipated top sellers,” defined as books whose authors receive an advance on royalties of $250,000 or more.

The merged entity of Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster would command roughly 50 percent of market demand for anticipated top sellers, the government argued, and the resulting reduction in bidders would harm authors of such books via diminished advances. Read admitted that these anticipated top sellers accounted for only 2 percent of books published each year, but argued that they account for more than 70 percent of what Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster spend annually on advances. The Justice Department was going to bat for the top 2 percent of authors, because that’s where the money is.

To this simple and intuitive argument—less competition leads to lower prices—the government added several less obvious points. The market, Read said, was already highly concentrated with the so-called Big Five (PRH, HarperCollins, S&S, Hachette, and Macmillan) controlling 90 percent of anticipated top-seller demand. No new competitor had emerged since the Seventies at the level of what was until 2013 the Big Six, and would now be, if the merger went through, the Big Four. Under current conditions no such competitor could emerge in the foreseeable future. Read quoted a 2019 report by the late Carolyn Reidy, the former head of Simon & Schuster, who described independent presses as “farm teams for authors who then want to move to a larger, more financially stable major publisher.” It was the first of many baseball metaphors to be invoked at the trial.

Read made it clear that he and his fellow government attorneys had no need to prove that advances would be reduced. He cited Section 7 of the Clayton Act of 1914, which prohibits mergers whose effect “may be substantially to lessen competition.” Since you can’t prove what will happen in the future, he said, “a predictive judgment, necessarily probabilistic and judgmental rather than demonstrable, is called for.” What was at stake was an “appreciable danger” of harm. In addition, the Supreme Court had decided that a merger could be presumed illegal if a merged firm would control 30 percent of a market. In this case, the portion was closer to one half. The probable harm to anticipated top-selling authors could be projected: between forty-four and sixty thousand dollars less for PRH authors; between a hundred and five and a hundred and forty thousand dollars less for S&S authors.

Read presented a slideshow that traced the auction for a proposal by “an author who wanted to write a compelling memoir of her life.” To protect both the author’s privacy and the defendants’ proprietary secrets, the details were anonymized. Over the course of the trial, names of authors and advances paid by other publishers were at times mentioned indiscreetly by various witnesses, but most examples were discussed in such a way that only the judge, the lawyers, and the witnesses knew what was being discussed. To make sense of the slideshows, they were in possession of “decoder rings” not provided to members of the public, which consisted of a few journalists, witnesses waiting their turn, and lawyers for witnesses and other parties. (One attendee who did not fit obviously into any of these categories was expelled from the courtroom after a rant about fascism; it was unclear whether he favored the merger.)

What happened to the author of the “compelling memoir of her life” was a five-day round-robin auction among seven publishers: Penguin Random House (initial bid: $550,000), Simon & Schuster ($510,000), Hachette ($300,000), Macmillan and HarperCollins (both less than $300,000), and Norton and Bloomsbury (both $100,000 or less). By the end of the second day, PRH had raised its bid to $645,000, S&S to $625,000, and Hachette to $605,000; the other bidders had dropped out. Hachette would drop out after raising its bid to $650,000. PRH and S&S continued to outbid each other by increments of $20,000 until PRH won with a bid of $825,000. “Remember when it was at 650? The only two remaining bidders were the defendants. It was only Simon & Schuster’s aggressive independent bidding that forces Penguin Random House to more fully pay what it believes the author’s book is worth,” Read said. “This author’s labor benefits by close to $200,000 because Simon & Schuster alone continues to compete against Penguin Random House. That competition is worth protecting.”

Over the next three weeks, the prosecution and defense rehearsed many versions of this auction breakdown. The government repeatedly showed that competition between PRH and S&S benefited authors. The defense trotted out its own examples to show that such auctions were won, or advances were raised, just as often by other publishers. It took on the feel of a war of attrition, and for the people in the room with experience in the book business, a rather boring one. Of course PRH won auctions a lot of the time but not all the time, and of course smaller publishers won auctions some of the time but usually dropped out when the numbers got too big. Small presses, as several witnesses testified, have to pick their “bets” or “slots” or “shots.” But it was not the editors, publishers, or agents who needed convincing. It was Judge Pan.

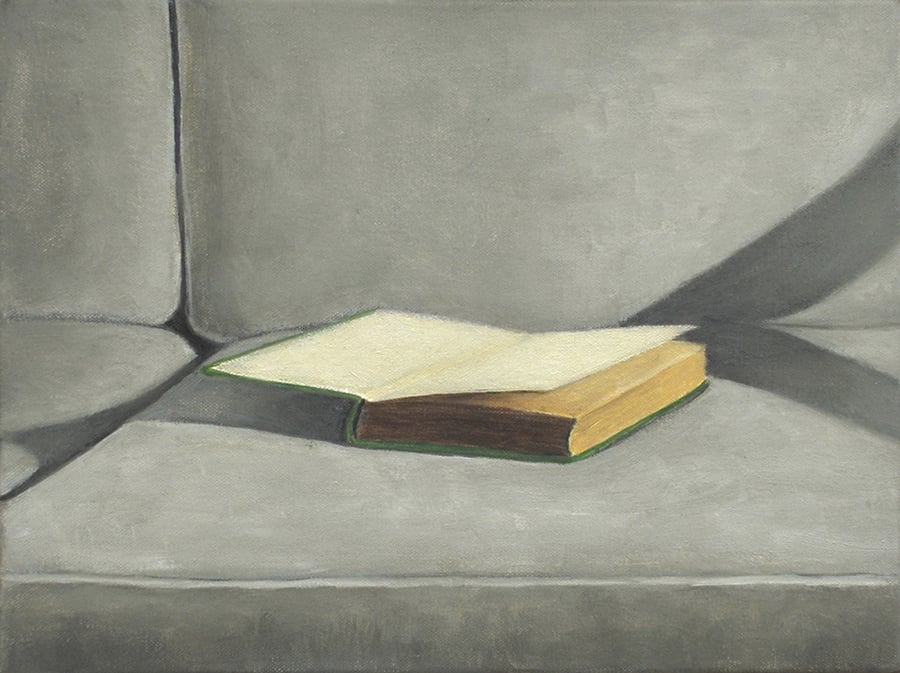

There is so much hope at the beginning, by Jess Allen

The view put forth by the government was that the publishing industry was a market like any other, that its practices were routinized, that its players followed rules, and that its dynamics could be predicted by the scientific methods of economists. The defense presented it as a casino full of hippies gambling unlimited piles of money generously provided to them by multinational corporations happy to cover their losses, as well as their lunches, while coasting on the enormous revenues generated by the entire history of human thought and feeling. If the hippies generally lost, sometimes they won big, and their winnings went back into the house kitty. If they won really big (as Random House did with Fifty Shades of Grey), then it was Christmas bonuses for everybody from the mail room to the corner office.

I am exaggerating, slightly. Daniel Petrocelli, the lead attorney for Penguin Random House, didn’t mention Fifty Shades or Christmas bonuses in his opening statement (though this did happen in 2012), nor did he call anybody a hippie. But he portrayed the government’s argument about a market for anticipated top sellers as a fiction. Advances paid to John Grisham, Stephen King, or celebrities such as Dolly Parton and the Obamas were “what this alleged market is about.” But such celebrities would “be the first to admit, they will not be harmed by this merger,” he said, noting that advances at that level are in the millions. By setting the boundary much lower, at $250,000, Petrocelli said, the government was including “debut authors, unknown authors, lesser-known authors,” who got such a sum not because of celebrity but as a result of an auction or a negotiation, because an editor hoped a book would become a top seller. “But, Your Honor, when you think about it, every book starts out as an anticipated top seller in the gleam of an author’s or editor’s eye, right? Every book is a dream,” he said. “And sometimes dreams come true. And sometimes they don’t. And the history of publishing is littered with very, very high advance books that flop and very, very low advance books that soar.”

To anyone even slightly familiar with the industry, this was undeniable. Big advances for authors without preexisting fame or a track record of sales resulted from a frenzy of industry buzz, and most of the time such passion did not pan out. Meanwhile, Cinderellas went from humble beginnings to big earnings, perhaps by catching the eye of Oprah Winfrey or Reese Witherspoon. Most of what happens is more banal; veteran authors generally receive advances in line with their sales records. Petrocelli said that the figure Read cited—that 2 percent of books accounted for 70 percent of advances paid—didn’t mean much because it wouldn’t translate into 70 percent of sales.

Petrocelli’s wider argument was that since new books constituted less than half the market in sales, and new books with high advances had only a rough correlation with top-selling books, the harm being alleged was insignificant. Given that there were 55,000 to 65,000 books published per year, 2 percent equated roughly to 1,200 books. The government’s antitrust expert, Nicholas Hill, a tall, bespectacled economist who would emerge as the hero or the villain of the trial depending on your point of view, said that of those books, 12 percent were acquired in competition between the merging publishers—about 130 books. By the defense’s more modest estimate, only 7 percent of high-advance books were sold in head-to-head competition between Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster: 85 books in total. The government projected a reduction of $29.3 million a year in advances—an insignificant number in a market of more than $1 billion.

That reduction would not happen, Petrocelli insisted, because competition in the industry was “fierce” and would only become fiercer. The best home for the authors of Simon & Schuster and their books was Penguin Random House, because it and its parent company, Bertelsmann, were the world’s leading stewards of books. And besides, the global chairman and CEO of Penguin Random House, Markus Dohle, had promised American literary agents that the editorial imprints of Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster would continue to compete with one another. For authors, it would be as if the merger never happened.

After Petrocelli finished his remarks, Stephen Fishbein, an attorney for Paramount Global, spoke briefly to insist that his client’s decision to sell Simon & Schuster was based on a new streaming business model, not on the whims of the market or corporate opportunism. “Simon & Schuster will be sold to somebody,” he said, “and that somebody, if it’s not Penguin Random House, is very, very likely to be another book publisher, because it’s the other book publishers who can obtain the highest efficiencies that we’ve been talking about, by combining their operations with Simon & Schuster.” Arguments from the CEOs of Hachette and HarperCollins that the merger was anticompetitive should be dismissed, he said, because their parent companies had sought to acquire Simon & Schuster and likely would renew those efforts if the merger were blocked.

His remarks evoked another specter hanging over the trial: that Simon & Schuster might instead be acquired, like many legacy media companies before it, by a private equity firm—which would load it with debt, lay off most of its employees, and sell off its parts, leaving nothing but a backlist to be peddled away at a discount. It was for this reason that many I spoke to in the publishing industry wanted to see the merger go through. As bad as it would be to see Penguin Random House get even bigger, they had friends at Simon & Schuster and didn’t want to see them lose their jobs. PRH would probably lay off plenty of them anyway, but Wall Street was worse.

Her favourites were the blue Penguins, by Jess Allen

The American publishing industry as it exists today is largely the remnant of a middlebrow revolution initiated during the Twenties. Dick Simon and Max Schuster founded their publishing concern in 1924. Their first products were books of crossword puzzles. Simon had a relative who compulsively solved puzzles from the New York World, and he figured there would be a market for books that collected them. Within a year, the first Cross Word Puzzle Book, put together by the World’s puzzle editors and priced at $1.35 with an eraser-topped pencil, together with its sequels had sold more than a million copies. The founders were still in their twenties and were soon rich men.

In a profile of the pair that Geoffrey T. Hellman wrote in 1939 for The New Yorker (another organ of the middlebrow revolution), Simon is portrayed as the sales guy and Schuster as the idea man. “Max is the spark plug and Dick the brake,” one of their friends told Hellman, who estimated that 80 percent of the ideas for the books they published came from inside the firm. Hellman detailed Schuster’s color-coded method for filing book ideas and other editorial memoranda. It spread from the pockets of his jackets to an elaborate system of drawers in the office, managed by multiple secretaries. After the partners took a loss in 1925, Schuster returned them to the black with Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy, a rewritten omnibus of nickel booklets about thinkers Durant had done for another publisher. (Durant continued publishing his The Story of Civilization series for fifty years, until his death at ninety-six, by which time he had reached The Age of Napoleon.)

Another Schuster idea was The Bible, Designed to Be Read as Living Literature, for which a professor from the University of Oregon was commissioned to “pep up this book by blue-pencilling the routine ‘begats,’ changing the punctuation, and inserting casts of characters, including the Lord, Satan, and so on, before passages like the Book of Job.” (Refreshing the Bible into something with a copyright is still common practice in American publishing and a big business for HarperCollins in particular, as its CEO Brian Murray attested during the trial.) The firm’s high ambition to deliver the world in its books was tempered by Simon’s motto, “Give the reader a break,” which he had printed on brass paperweights.

One of S&S’s first editorial hires was Clifton Fadiman, who arrived at his interview with a hundred ideas for books, one of which was a compilation of Robert Ripley’s Believe It or Not! newspaper columns. Fadiman had graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Columbia, where he was a classmate of Lionel Trilling and Whittaker Chambers. He’d wanted to continue there but was told by the chairman of the English department, “We have room for only one Jew, and we have chosen Mr. Trilling.” As editor in chief of S&S he commissioned Chambers to translate Felix Salten’s Bambi, which Simon had brought back from a trip to Europe. The firm’s business manager, Leon Shimkin, attended Dale Carnegie’s public-speaking course and convinced his teacher to do How to Win Friends and Influence People as a book even though he’d be giving away the contents of a $75 class for $2 a copy. After this success, Simon and Schuster offered him a $25,000 bonus, which he turned down, asking instead for a stake in the company.

In 1939, the three partners joined Robert de Graff to launch Pocket Books, a mass-market paperback line. In 1944, Marshall Field III, founder of the Chicago Sun, bought both S&S and Pocket Books. After Field’s death in 1956, Simon, Schuster, and Shimkin repurchased S&S. (Simon retired in 1957 and died soon after. His daughter Carly went on to fame as a pop star.) Schuster retired in 1966, and control of the firm went to Shimkin, who merged it with Pocket Books. By this time, the editor in chief, Robert Gottlieb, had brought the firm distinction as a publisher of fiction, with novels such as Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and Charles Portis’s True Grit. In 1975, Shimkin sold the company to Gulf + Western, a manufacturing and resource extraction conglomerate that had moved into the entertainment business with its purchase of Paramount Pictures in 1966. In 1989, Viacom bought the rebranded Paramount Communications. Ten years later, it bought CBS. It spun CBS off in 2006, until the 2019 remerger that put Simon & Schuster on the block, setting the stage for the attempted merger with Penguin Random House.

In fact, S&S and Random House had themselves long been intertwined. Soon after deciding to leave Liveright Publishing to start his own house, Dick Simon got lunch at the Hotel Pennsylvania with his friend and Columbia classmate Bennett Cerf. “I was bored with Wall Street, and Dick’s superior career infuriated me,” Cerf told Hellman in his own New Yorker profile in 1959. “I called up my office and resigned.” He joined Liveright as vice president and, in 1925, purchased the Modern Library series of classics from his boss. In 1927, Cerf and his partner started a new imprint to publish, “at random,” the sort of handsome limited editions they were fond of collecting. In 1934, Random House put out an edition of Joyce’s Ulysses, which had been banned in the United States. Cerf fought the ban in court and won to great fanfare. The victory solidified his reputation as a champion of modernism. Meanwhile, he cultivated a symbiotic career as a celebrity panelist on game shows and an author of joke books, many of them published by Simon & Schuster.

The revolving door of New York publishing, the way editors often advance their careers by taking jobs with their employers’ rivals, was made clear at the trial. Most of the witnesses had worked at multiple publishing companies, often for iterations of both PRH and S&S. Simon & Schuster CEO Jonathan Karp’s thirty-three years in book publishing have included stints as the editor in chief of the Random House imprint (“Little Random” in the biz), and the publisher of Hachette’s Twelve imprint, which he started in 2005. Karp has also written an off-Broadway production and made several cameo appearances as a book editor on Gossip Girl. Many refer to him casually as a “theater kid,” and few witnesses could rival his flair.

Called by the prosecution, Karp was the first witness to exhibit any hostility to his questioner, though it was of a mild, playful sort. The Justice Department lawyer Jeffrey G. Vernon, pointing to the transcript of Karp’s pretrial deposition, said, “Before I point you to a specific page, can I ask you: Fair to say I did take your deposition in this case?” “Oh, it was—yes, that’s very fair,” Karp replied. “It was about fourteen hours.” “That’s okay,” Vernon said. “Touché.” Vernon’s initial questioning focused on auctions that ended in direct competition between S&S and PRH. There was the case of an “artist” Karp had been chasing for more than a decade, going back to the time he had worked at Hachette, whose “magnitude” was such that “anybody could have offered” to buy the book. A PRH imprint, Karp said, just happened in this case to be “the manipulative stalking horse” that drove his offer up from $6 million to $8 million. Vernon noted that Karp had denied in a prior deposition that PRH had influenced his offer at all. Karp apologized.

By saying “anybody could have offered,” Karp was implying that the Big Five publishers are essentially interchangeable when it comes to bidding on big books. Who is in the game depends on the whims of the agents who set up the auctions, how lucky the editors are feeling that week, and which publishers happen to be employing them at whatever stage they’re at in their merry-go-round careers. Many witnesses both for and against the merger put forth some version of this idea, but Karp’s was the most persuasive. Another tense moment between him and Vernon occurred when the attorney read out an email Karp had sent his boss, Carolyn Reidy, in September 2019, in which he said, “This was the third beauty contest we lost this week to PRH.” The following exchange ensued:

Vernon: And a beauty contest is a situation where two publishers’ offers for the same book are similar financially and the publishers then compete on non-financial terms or factors to win the book, is that correct?

Karp: Pulchritude.

Vernon: Pulchritude?

Karp: Yes, it’s beauty.

Vernon: Beauty. Okay. I should have guessed that you would have a big vocabulary as the head of a publishing house. As an example, in a beauty contest, Simon & Schuster and Penguin Random House might try to compete to convince the author that they will do the best job marketing a book, is that fair?

Karp: That they have the best vision for publishing the book overall. It could be many things. Sometimes it’s the editorial connection. Sometimes it is the marketing or the publicity. Sometimes it’s just the sum of the enthusiasm that the house has.

Vernon: And in this email, you state that Simon & Schuster lost three beauty contests in one week to Penguin Random House, is that fair?

Karp: It was an ugly week. But you’ll also find emails bemoaning losses to HarperCollins and Macmillan and our other competitors.

Vernon: I understand. Just since we have limited time, let me ask you to try to focus on my question, and then I’m sure your counsel will be able to ask you about that?

Karp: You got it.

Under cross-examination by Fishbein, Karp did indeed rattle off many losses, and in a break from protocol, since he wasn’t discussing evidence of auctions between S&S and PRH that were subject to redaction, he named names: the musician Dave Grohl, the right-wing podcaster Ben Shapiro, and the novelists Kate Morton and Brad Meltzer to HarperCollins; the actor Jamie Foxx and the Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson to Hachette; and the journalists Alec MacGillis, Noam Scheiber, and Jiayang Fan to Macmillan. Oprah Winfrey, who is affiliated with the Macmillan division Flatiron, was a formidable nemesis. Among smaller presses, Norton had retained the astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson despite S&S’s wooing. The reporter Michael Lewis and the writers Richard Powers and Mary Roach were known to be loyal to Norton, and attempts to poach them had been futile.* Karp had lost authors to Scholastic, academic authors to university presses, and a coveted book called High Fiber Keto to the California-based mind, body, and spirit publisher Hay House. Karp said he disdained the term Big Five as “parochial and ethnocentric. There are a lot of really good publishers all over the country. I don’t think it’s all about us.”

Karp ventured further when questioned by Vernon on the advantages that Big Five publishers hold in publicity and marketing: “A lot of us believe that a good editor, a good publicist, and a sales rep is enough.” Vernon kept pressing, and Karp, imagining a scrappier career for himself, lapsed into the subjunctive: “If I were working for a small publisher, I might think that I’d be just as good.” Here was a refreshing assertion of non-institutional self-confidence. (This testimony was submitted by Vernon for impeachment with Karp’s pretrial deposition.) Karp stressed that he tried to maintain the spirit of “enterprise” that animated Dick Simon and Max Schuster, finding authors and bringing them ideas, not simply waiting for submissions from agents.

Vernon quoted two emails from Karp, sent before his promotion to CEO and the announcement of the purchase of S&S by PRH, that cast doubt on such a merger. On March 5, 2020, the day after it was announced that ViacomCBS was selling S&S, one of Karp’s authors, the novelist John Irving, wrote to him: “Naturally, I’m inclined to imagine an ironic sale; generally, irony is more satisfying in fiction than in real life. Such as S.&S. is bought by Penguin Random House and I find myself back in the hands of publishers I thought I left.” Karp replied: “I’m pretty sure that the Department of Justice wouldn’t allow Penguin Random House to buy us, but that’s assuming we still have a Department of Justice.” His joke, as he called it during cross-examination, turned out to be correct, and his anxiety about the Trump Administration overblown. “I think you could say quite accurately that I was almost entirely ignorant,” he testified. “My parents wanted me to go to law school and I didn’t listen.”

The second email, from September 11, 2020, struck a more serious note. It was written to Alex Berkett, a Viacom executive managing the sale of S&S, who had expressed concerns about the difference between a sale to another publisher (a strategic buyer) or a non-publisher (a financial buyer): “Although I really do understand why strategics are the most likely option, if there is a financial buyer who is willing to match the top bid, that outcome would be better for the employees of S&S and arguably the larger book publishing ecosystem.” Karp never clarified why he thought a financial buyer would be better, though many in the industry have pointed to the acquisition of the booksellers Waterstones and Barnes & Noble by Elliott Investment Management and their subsequent expansion as evidence that private equity isn’t always bad for the book business. He may have been thinking about the layoffs and consolidation that followed the previous merger and the very anticompetitive effects alleged by the Justice Department lawyers.

Fishbein then pointed Karp to the emails he wrote to S&S employees on November 5, 2020, the day after the sale to PRH, expressing his “elation.” A few weeks later, he wrote to Irving that he was “delighted” by the sale. Under redirect examination, Karp was asked by Vernon whether he would receive a bonus if the merger went through. Karp said that such a bonus was a standard provision of his contract. Vernon asked if he expected to have a role at the combined company. “I haven’t really thought much about it, but yes,” Karp said. “Yes, I would like to. I would rather not do my job interview right now with you, if that’s okay.”

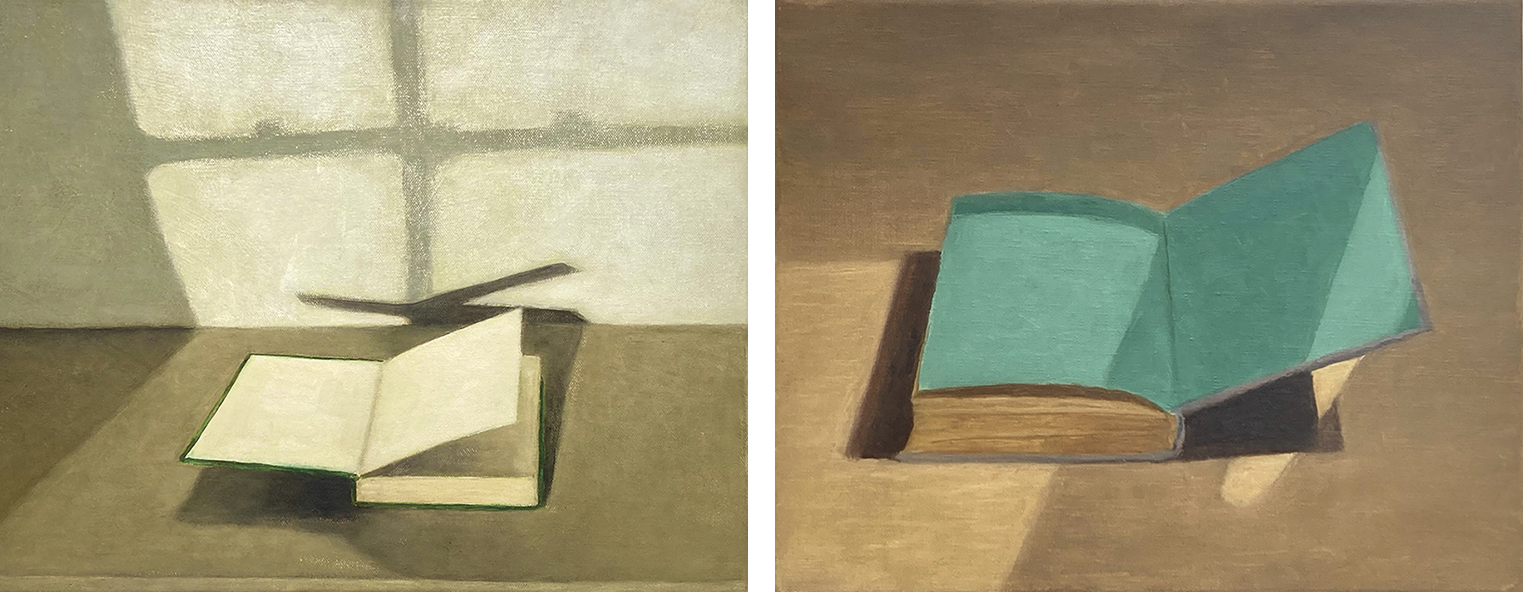

Paperbacks 3 and Paperbacks 4, by Jess Allen

As a freelance writer, I have a hard time feeling sympathy for a publishing executive whose bonus may be on the line if the government blocks a multibillion-dollar merger. At the trial, authors and their agents constituted the class of people the government was defending from harm (authors explicitly, and agents by extension, since they are compensated on the basis of authors’ earnings), but only three authors testified, two of whom favored the merger.

Four agents took the stand, three in favor and one against. This could be put down in part to the defense mustering the support of their business partners, who, if not exactly loyal, were canny enough not to run afoul of what was already the biggest gravy train in town, potential anticompetitive effects be damned. And as for those effects, they were smart enough to still get their authors—and themselves—paid. One former agent, Jennifer Rudolph Walsh, testified that Penguin Random House had paid her $250,000 to take the stand. (The four working agents appeared gratis.)

The striking thing about the writers who testified was how rich and successful they all were: Andrew Solomon, Stephen King, Charles Duhigg. Solomon is the author of several books, among them The Noonday Demon, about depression, and Far from the Tree, about families with disabled or otherwise atypical children, both bestsellers. Like many witnesses, he appeared in a prerecorded video deposition. He seemed to be speaking from a very well-appointed living room. In addition to testifying to the excellence of the way Scribner, an S&S imprint, publishes his books, he confirmed that he is a personal friend of Dohle and independently wealthy.

“My name is Stephen King. I’m a freelance writer,” the seventy-five-year-old novelist said, as though he were at an AA meeting that happened to be populated mostly by lawyers rather than by alcoholics (or freelance writers). The story of King’s publishing history is a fascinating one, as such stories go. He published Carrie with Doubleday in 1974, with no agent, and received an advance of $2,500. He received no royalties from the film adaptation, but “Signet published a movie tie-in edition and that did very well.” After five books with Doubleday, all of which received low advances but turned out to be bestsellers, King accepted the representation of Kirby McCauley, an agent for “a lot of old-time horror and fantasy writers,” whom he’d bumped into at a party for the romance writer Helen Van Slyke. McCauley convinced him to go to Doubleday with an offer of three books and an ask of $2 million. “And the man who’s negotiating on Doubleday’s behalf,” King said, “a man named Robert Banker, laughed and walked out of the restaurant.”

McCauley got King his $2 million from his paperback publisher, New American Library, which then sold the hardcover rights to Viking (now an imprint of PRH but then merely an imprint of Penguin). King stayed with Viking for about fifteen years. After McCauley retired in the late Eighties, King’s business manager Arthur Greene sought “an equal amount of money to what Tom Clancy was making. . . . Something like $64 million for three books,” King said. “And it was way above what the projected royalties would have been, but he wanted to keep up with Clancy. It was not a good business decision because he wasn’t a real agent.” His editor at Viking, Chuck Verrill, who was leaving the house, told Greene that Scribner was interested in King: “What they offered at that time was almost like a co-publishing deal, where I would share in a lot more than 10 percent or 15 percent of the royalties—that I would get 40 to 50 percent—but I would have to share in the expenses, the publicity, and I would have to do a certain amount of promotion of the books and that sort of thing, which I was happy to do because I loved the people that I was working with.” Verrill worked with King on his first “two or three” books with Scribner, at which point its then editor in chief, now publisher, Nan Graham became his editor. Along the way, King published various books that were outside his usual horror fare (The Gunslinger, The Colorado Kid, Blockade Billy) with smaller specialty publishers. These books would inevitably become bestsellers. “I don’t know,” King said, when asked how many bestsellers he had published. “Probably sixty, sixty-two, sixty-five.”

As far as I could tell, King was the only witness who attracted autograph seekers outside the courthouse, one of whom lit my cigarette during a recess. When we returned to order, King explained his reasons for testifying. “I came because I think that consolidation is bad for competition. That’s my understanding of the book business. And I have been around it for fifty years,” he said. “When I started in this business, there were literally hundreds of imprints, and some of them were run by people who had extremely idiosyncratic tastes, let’s say. And those businesses one by one were either subsumed by other publishers or they went out of business.” It should be said there are still hundreds of small presses in the United States as well as publishers with idiosyncratic tastes, but they are smaller and less viable than they used to be, before they were dwarfed by five giant corporate publishers. He cited a 2018 Authors Guild of America survey that said that the median full-time writer makes around $20,000 a year.

King closed with a series of simple metaphors, about publishers as consignment shops, closing one by one, or sports agents looking to place their baseball players, to find there are only five teams. Finally, with regard to competition within a merged PRH and S&S: “Well, you might as well say you’re going to have a husband and wife bidding against each other for the same house. The idea is a little bit ridiculous when you think about it.”

Open Book, Winter Light and Green Endpaper, by Jess Allen

Charles Duhigg is a forty-eight-year-old New Yorker contributor and the author of two best-selling books, The Power of Habit and Smarter Faster Better. Over the years I have seen him around at parties in Brooklyn, and he always seemed a good-natured fellow. I have never been interested in his books because I avoid anything that smacks of self-improvement and any books with the words “power” or “better” in their titles. Having been subpoenaed to appear at the trial, he was largely under the burden of testifying to how prosperous he has become as a Random House author, and his performance was rather uninhibited. At moments I had the impression that he was a motivational speaker talking directly to me. While earning an MBA, Duhigg decided that he would rather be a journalist than a businessman. He joined the L.A. Times before being hired by the New York Times, where he was part of a team of reporters that won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory journalism. He started working on a book proposal that took him a year to write. Around this time, an agent from the Wylie Agency contacted him with the idea that a piece he had written on the psychology of credit cards might make a good book. Duhigg countered with the proposal he was working on, which the agency submitted to Andy Ward, an editor at the Little Random imprint, who bought it with a preemptive offer of $750,000.

On the subject of Ward, Duhigg gushed. Ward’s name could justly appear on the spine of Duhigg’s first book. He was the only reason for its success. He referred to the process as “me and Andy writing.” As a former magazine editor, I found these effusions both endearing and embarrassing. The editorial process Duhigg described—one of memos, line edits, notes, and revisions—sounded pretty standard.

Duhigg’s larger point soon came into view: not only did he have a great editor, he got to pick his book jacket out of “thirteen or fifteen” different mock-ups “to try and figure out like which one is going to attract the reader’s eyes when it’s sitting there on a shelf”; he had publicists and marketers who “worked tirelessly” to get him “on Terry Gross and to tell me which podcasts I should do”; he had sales reps who knew the difference between “how you talk to the Costco in Des Moines” and how you talk to “Books Are Magic, which is my favorite bookstore in Brooklyn”; he had “data geeks who figure out that someone in Des Moines who works in tech likes books like mine and that if we serve them an ad on Facebook at 7 pm, they might see that ad.” In the end, “there were literally like hundreds of people who knew something precise and helped,” he said, and once the book came out, “they really, like, lean in.” His tone when it came to publishing professionals was consistent with the reverent presentation of certain doctors, scientists, and other experts in his books.

Then there was Duhigg’s advance. It was just the right size: enough for him to take unpaid book leave from his job, with a little cushion to boot, but not so much that his book wouldn’t earn out—that is, fail to sell enough copies for the actual royalties to match the (non-refundable) advance against them—since not earning out might hinder his chances of continuing to work with Andy Ward. “There’s a certain size of advance that makes sense,” he said. “In excess of that is dangerous.” Too much money too soon was a source of fear. “I would be very scared,” he said, “that it means that Random House would not want to work with me anymore, because they lost money.” When Andrew Wylie suggested shopping his third book for an advance of up to $5 million, Duhigg testified, he refused. “I specifically said I did not want to do that. It’s a very, very bad idea to take a very large advance.” (Wylie denies making such a suggestion.) Duhigg received a more modest $2 million for the third book, “about the science of communication and conversation.”

Yet many had testified that the majority of authors, particularly at high levels, do not earn out their advances, and that accepting large advances was the only way to attain a guaranteed income. Judge Pan congratulated Duhigg on his success, then asked: “So what about authors who don’t earn out their advances? And we’ve heard in this trial that 85 percent of books don’t earn out their advances. What if you’re an author who didn’t earn out their advance but you want to write a second book?” Duhigg asked for clarification. “I’m not a lawyer, so I don’t understand a lot. But my understanding was that the group that we’re talking about are likely expected bestsellers. For someone who is an expected bestseller, you anticipate that you will earn royalties in excess of your advance. Like that’s the whole point of being a bestseller.”

He tried to imagine life after not earning out. “So I think if you’re an author who didn’t—and this happens a lot. I have a number of friends who, whether it’s their second book or their third or fourth, like, it’s going to happen to me. There’s some book I write that won’t earn out its advance. So I guess—I’m sorry. What’s the question?” He returned to himself. “So I think for folks like myself, I’m very typical. Right? So I’m a professional writer. I have twenty years of writing experience. And I’m a non-fiction writer. You’re not going to find a lot of New York Times reporters, for instance, who write books that don’t succeed in some way. Right?”

Judge Pan pointed out that writers with such credentials represented a small portion of authors. “And there’s a lot of data that I’ve been presented with in this case that suggests that you are not typical,” she said.

“I’m not certain that there’s anyone who’s typical,” he said. “Right?” After all, there were poets whose sales would never match their talents. There were science fiction writers who toil in obscurity for years and then “become this huge hit overnight.” There were people who write books on the side and “never really want to be huge writers.” “There’s writers who write bad books—not bad books, but they don’t write great books because they know that they’ll get invited on the lecture circuit. I know, like, five or six of these guys. And they’re great. Right? They give great lectures. But you need a new book to, like, remind people that you give good lectures. And so the thing I would say is, you’re right: I am atypical. But every author is atypical.”

The questioning was inconclusive. But for Duhigg, the writing life was simple: “It’s this chain, chain link. Right? Like: I get the book on track. I write this book. I use the advance to finance writing the next book. Hopefully, the book I just wrote, the revenues—royalties start coming in eventually, and so that’s how I pay for my kids’ college.” According to his testimony about his own royalties, foreign and domestic, as well as speaking fees, it would stand to reason he could put several kids through Harvard at full tuition, though perhaps not as many as Stephen King could. “Nobody knows who I am. Like nobody knows who Charles Duhigg is. And the market—like the world is different now that you can’t be Stephen King. You can’t even be Malcolm Gladwell. Like it’s just—that age is over.”

Duhigg seemed genuinely confused when Judge Pan asked him about writers who didn’t earn out their advances, the “whole point of being a bestseller” being to do just that. The exchange spoke to the existential question at the heart of advances: are books, book proposals, and authors valued according to some notion of inherent worth, some unrealized potential, a track record that might be duplicated, or a gut feeling about future market appeal? Taking the stand a few hours after Duhigg, Andrew Wylie gave the most forceful rejection of the notion of anticipated top sellers:

Petrocelli: There’s been talk in this trial about something called anticipated top-selling books. Is that an expression in the course of your career with which you are familiar?

Wylie: I am familiar with it, but it is not part of the business that we are active in.

Petrocelli: What do you mean by that?

Wylie: We don’t represent top-selling authors. We don’t represent authors like John Grisham or Danielle Steel or—

Petrocelli: Why not?

Wylie: Because what we are aspiring to do, to be selfish, is enjoy the work that we’re representing, enjoy reading it, and I—and not to have our primary goal be purely financial but, rather, to be literary. And I would argue that the performance of works of interest is stronger over time than the purely commercial work, which flares and dies quite rapidly.

Wylie and his agents were strictly in what Terry Southern called the Quality Lit Game. “From the beginning,” Wylie said, “we seek out books of high quality, both in fiction and non-fiction. It interested me that the books that received the highest advances and the most prominent distribution were not books that I deemed to be of great quality, and I felt that the—the highest quality books were not either well represented or well published. So that was the area that we looked at, and we’ve continued on that path for forty-two years.” If his practice happened to yield occasional bestsellers like Duhigg’s or Solomon’s, it was because of an accelerated market appraisal of their eternal merit, not because Wylie and his colleagues were engaged in something so crass and unpleasurable as pure commerciality. I happen to share Wylie’s views on this matter, if not his exact taste (the Wylie Agency represents about fifteen hundred authors, some of whom, as a critic, I have praised and some I have panned), and so his appearance at the trial came as a relief. Here was a man determined to restrict his activities to the realm of the plausibly literary or intellectual and who was not shy about saying so, a man who considered his profession, and reading itself, a hedonistic activity. He favored the merger because he thought PRH would make a better owner than whatever private equity shop would be the likely alternative. Here, too, was a man who does not like to play by rules. For that reason he and his agents do not conduct auctions. They simply submit manuscripts and proposals to publishers. In a pretrial deposition, Wylie had been asked, “Do you believe it’s your role as an agent to try to get an advance that an author doesn’t earn out?” He answered, “Correct.”

On the stand, Wylie qualified his remark: “I think I’ve said that with levity as much as profundity.” He went on: “If the book is going to earn a hundred dollars and the author is paid two hundred dollars, then the author is happier than if the book earned a hundred dollars and the author was paid fifty dollars.” While he admitted that earning out advances was a “complicated question,” he also admitted that he estimated that only 5 percent of the books he represents earn out their advances. Wylie built his reputation on poaching famous authors from other agents and extracting enormous advances for their next books. In 1995, he lured Martin Amis away from his longtime agent, Pat Kavanagh, and got him an advance of nearly $800,000 for The Information. (Amis wrote in his 2000 memoir, Experience, that he spent some of the money fixing his teeth; he also fell out with his old friend Julian Barnes, Kavanagh’s husband, over the switch.) It was around this time that Wylie earned his nickname the Jackal for his cunning and aggressiveness.

Wylie’s gambits are not always successful. During his cross-examination, Wylie was asked about a project of his called Odyssey Editions. The notion was to offer authors an e-book royalty rate higher than the going rate at the time, which was 25 percent. On the stand he said he “felt that were it not increased by publishers, that they ran the risk of losing control of those rights because the authors would publish digitally outside of their print publishing agreements, and that would be damaging to the fundamentals of the publishing industry.” Wylie offered authors whose books had not yet entered e-book agreements with publishers, many of them Random House authors, a royalty rate of 100 percent, minus a commission for him, to publish their e-books. Twenty books entered this agreement. Random House responded by announcing it would no longer do business with Wylie. Wylie and Dohle met personally, and the Random House books in question were withdrawn from Odyssey Editions. The standard industry rate for e-books remains 25 percent. As another witness put it, “Agents do not have a magic wand.”

Dohle attended the entire trial. He is a tall man who tends to wear sharp blue suits, and his German accent might recall a Bond villain if he weren’t so charming. Among the daily observers, he and I probably laughed the most. Born in West Germany in 1968, he joined Bertelsmann in 1994 and spent his first eight years in sales and distribution. “I’ve basically worked in the entire value chain of books in the almost thirty years at Bertelsmann,” he said on the stand, “and I did it in reverse.”

Bertelsmann is a privately held corporation headquartered in Gütersloh, Germany, where it was founded in 1835 as a publisher of Evangelical literature by Carl Bertelsmann. Its nearly two-hundred-year history is bisected by the Second World War. By the Thirties, the firm was in the hands of Carl’s great-grandson Heinrich Mohn. In 1998, a commission appointed by the company to investigate its conduct during the Nazi era, headed by the historian Saul Friedländer, found that it profited from selling “field editions” of adventure books to the Wehrmacht, many of which had anti-Semitic themes; that Mohn, though not a member of the party, belonged to a group of patrons who made monthly donations to the SS; and that forced Jewish labor may have been used at printing presses it contracted in Lithuania. The firm was shut down by the German government in 1944 on suspicion of hoarding paper. In 1946, Mohn received a license to resume publishing from British occupying forces, but after his ties to the Nazis were uncovered in 1947, he was stripped of the company and it was put in the hands of his twenty-six-year-old son, Reinhard.

A member of the Luftwaffe who was captured by U.S. forces while serving in Tunisia in 1943, Reinhard Mohn cited his time as a prisoner of war at Camp Concordia in Kansas, where he read American business management manuals, as formative to his future career. He expanded Bertelsmann’s publishing business through subscription book clubs, then entered the music market. The company is now a major owner of magazines, newspapers, television stations, and printers, in addition to its publishing and music concerns. It entered the American publishing market with the partial acquisition of Bantam in the late Seventies, and purchased Random House from S.I. Newhouse’s Advance Publications in 1998. In 1977, Mohn founded the Bertelsmann Stiftung, an international neoliberal think tank that also runs an opera contest. The foundation now owns 81 percent of Bertelsmann; the other 19 percent is mostly controlled by the Mohn family.

In 2004, Dohle became Bertelsmann’s global head of printing. In 2008, he moved to New York to head Random House, overseeing the merger with Penguin in 2013, which he described as essential to the publisher’s success. Whereas Karp represented literary flair, chumminess with authors, defiance of “conventional wisdom in the publishing world” (he had acquired Laura Hillenbrand’s Seabiscuit early in his career despite being told that books on horse racing never sell), and the old-school values of the “idea man” like Max Schuster, Dohle represented a more technocratic strain in modern book publishing. Karp named dozens of authors casually in the course of his testimony, but Dohle cited only two: Britney Spears, the rights to whose book PRH had reportedly lost at auction to S&S for $15 million; and Eric Carle, the author of The Very Hungry Caterpillar, who sold his intellectual property to PRH before his death in 2021. (Carle’s books are currently published by S&S in the United States.)

Dohle’s testimony departed from the ritual litany of deals that had gone one way or another between PRH, S&S, and their rivals, because only advances of $2 million or more required his approval. Instead of questions of specific instances of head-to-head competition, Dohle was pressed on larger issues: the emergence of new competitors; the way PRH views Amazon; the threat of self-publishing; the importance of printing and distribution; the rationale and aftereffects of Random House’s merger with Penguin; the transformation of the business because of e-commerce; and looming threats to corporate publishing. Read centered his early questioning on a presentation Dohle and other PRH executives had prepared for an imprint they were considering creating with “a very famous public figure.” In addition to laying out the obstacles to starting a new house independently (principally, that it takes years to see any profits, if ever), the presentation put forward some basic facts about the business: that at its core it was about acquiring a “bundle of rights”; that the “agent landscape” was “fragmented”; that “publishers acquire rights in fast-moving competitive auctions”; and that “publishing is a portfolio business, with profitability driven by a small percentage of books.” Dohle elaborated on the last point: “Yes. We invest every year in thousands of ideas and dreams, and only a few make it to the top. So I call it the Silicon Valley of media. We are angel investors of our authors and their dreams, their stories. That’s how I call my editors and publishers: angels.”

It sounded like bullshit, but it wasn’t exactly untrue, or at least not any less so than other models of the relations between publishers and authors that emerged at the trial: that of publishers providing “services” to writers, of “partnership,” of casino-style “gambling,” or of long-term “nurturing.” It was in Dohle’s testimony that the merger seemed most benign. Describing the rationale for Random House’s merger with Penguin, he said it was “the same as it is here with Simon & Schuster: We were convinced that, given our investments in supply chain, back then already into speed, into in-stock rates, into faster replenishment, we were convinced—and it’s widely acknowledged in the retail community—that we could sell more of the Penguin books by giving their imprints access to the, by far, best sales and supply chain network in the country.” As for the creative side of the business: “I always said, This is the most boring merger of all time, quote. The only thing we are doing is we are bringing two communities of imprints, Random House and Penguin, communities of imprints, into one. And they continue to act editorially, creatively, and entrepreneurially independent.” In Dohle’s vision, everybody in the book business—publishers, agents, authors, publicists, cover designers, sales reps, printers, truck drivers, warehouse owners, independent booksellers, Amazon—were partners, and the more the books moved, the more money for all. If only every book could be a top seller!

Dohle was asked about his pledge to agents that the independence of PRH and S&S imprints would go beyond the rules of internal competition already in place at PRH: that instead of imprints bidding until there was no lingering external bidder, PRH and S&S imprints would act as separate entities until the end of competitive auctions. Read pointed out, and Dohle admitted, that the pledge was not legally binding and that his own contract with Bertelsmann expired in a few years. Under cross-examination by Petrocelli, Dohle elaborated: “If you grant your trusted business partners, in this case, agents and authors, an additional service, an additional, call it advantage, you are unable—practically unable to take it away. It would undermine that trustful relationship. I think it would damage our business in that agents and authors would not appreciate it and would feel betrayed.”

For three weeks, I lived in a hotel down the street from the headquarters of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. My social connections in Washington are few. I met with a couple of editors, and drank with a few writers, some of whom were also covering the trial. I had dinner with a couple of friends from college and their young children. I told them about Stephen King’s testimony. “Who is he?” their ten-year-old daughter asked. “He wrote books we read when we were your age,” I told her. “We shouldn’t have been allowed to read those books so young,” her mother said. “Oh, we were fine,” I said. “The books were good for us. I loved It.” “What’s It about?” the daughter asked. I told her it was about a clown who terrorizes children in a small town in Maine and then comes back to terrorize them again when they’re grown-ups. “I wanna read that,” she said. I told her I would get her a copy for her birthday. “Oh no you won’t, not yet,” said her mother. “A clown like Pennywise?” her daughter asked. “Too late,” I told her mother. It wasn’t the most literary conversation I had in Washington, but it was close. Books can be powerful things, overspilling any boundaries we draw for them.

One afternoon after the trial had ended, I was stopped on the Metro platform by a man I recognized from the courtroom. “I gotta ask, How is it?” He was referring to the book I’d been carrying throughout the trial, Heat II, by the filmmaker Michael Mann, the subject of another article I was writing over the summer. “It’s pretty good,” I told him, “but it’ll probably be better as a movie. It debuted at number one on the New York Times bestseller list this week.”

The man was Nicholas Hill, the economist who had developed the government’s arguments about the harm the merger might do to authors. Grounded in charts, models, percentages, projections, and, especially, diversion ratios, his testimony was complicated, but the idea was simple: when two competing entities merge, the assets they compete for directly will go to the merged entity, and the price of those assets will thus be depressed. The defense’s expert witness Edward Snyder, an economist at Yale, attempted to cast doubt on Hill’s models—they couldn’t account for bilateral negotiations, the data were insufficient, too much was merely projected—but it was Hill’s testimony that won the day. In October, Judge Pan issued a decision enjoining the merger. In her decision, Pan cited Dohle’s pledge that the companies would continue competition in auctions as “consciousness of guilt,” a tell that the merger was against the law.

Bertelsmann announced immediately that it would seek an expedited appeal of the decision. But on November 21, Paramount announced that it would not move forward with the sale. Under the terms of the deal, Penguin Random House owed Paramount $200 million, to go with the reported $50 million it had spent defending the merger in court. Within weeks, Dohle had announced his resignation. The merger had been his gamble, and sometimes when you lose, you lose big.