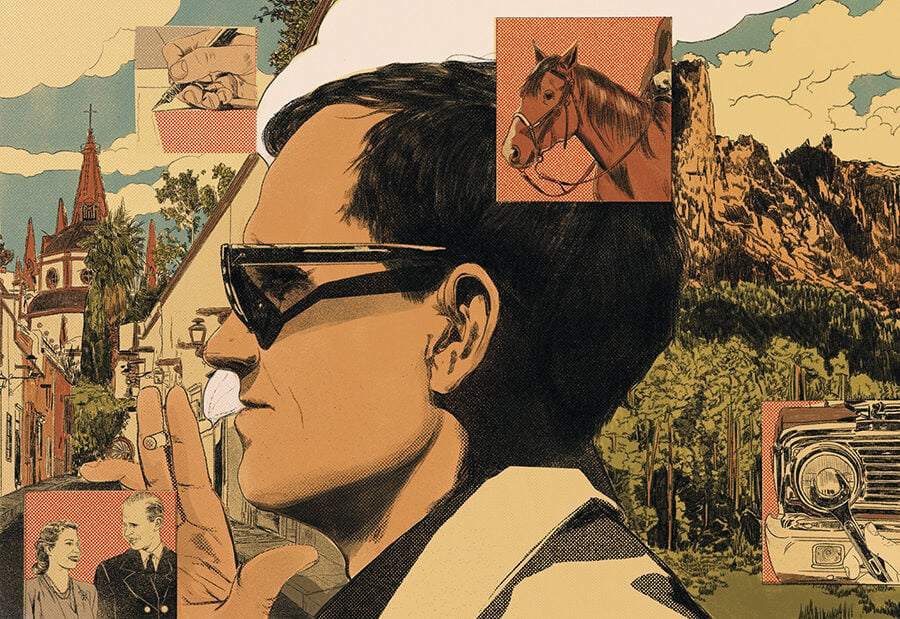

Illustration by Nicole Rifkin

Discussed in this essay:

Collected Works, by Charles Portis. Library of America. 1,105 pages. $45.

Not long before Charles Portis visited Buckingham Palace in the summer of 1964, having secured a rare invitation to “Her Majesty’s Afternoon Party,” he found himself in a one-bedroom apartment getting summarily hammered with a group of foreign correspondents. Portis was by then mostly inured to the aura of celebrity. Born in 1933, he’d been raised along the southern border of Arkansas, in that region one of his narrators calls “the Arklatex”—where Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas converge—before serving in the Korean War. He’d spent stretches of his earliest years in journalism trailing Elvis and Martin Luther King Jr. As the London bureau chief of the New York Herald Tribune, he’d already interviewed Marlon Brando and reported from the set of Goldfinger. The queen, though, was something else. “I began to wonder about protocol,” he later recalled. “Better be careful here.”

His time in London had been marked by noxious and near-constant concerns over protocol. He resented the city’s bureaucracy, its weather, the tailored suit jacket he wore every day to work. “He never liked London from day one,” his friend and former colleague at the Arkansas Gazette Roy Reed would later remember. “It was cold, damp, and the people were pretentious.” Added to this was his growing contempt for the institution of journalism itself, and consequently for other journalists. “I must have thought it would be fun and not very hard,” he once said of his decision to study journalism. “Something like barber college—not to offend the barbers. They probably provide a more useful service.” His low opinion of his own field, not historically all that uncommon, developed early. As he put it in a column for the Gazette when he was only twenty-four, “Show me a reporter and I’ll show you an arrested cretin.”

On this particular night in London, Portis and the others were playing cards in a room thick with smoke. One of the men leaned forward and showed off a trick in which he placed a lit cigarette on the end of his tongue, rolled it back into his mouth, and appeared to swallow it. Then he opened his mouth, stuck out his tongue, and revealed the still-lit cigarette—good as new. (The move would later make an appearance in Portis’s 1991 novel Gringos.) With bravado and boozy confidence, Portis placed his own cigarette on his tongue, leaned his head back, and tried folding it in, only to land the lit cherry on the tip of his nose, where it smoldered for a few moments before he shook it free.

The day of the queen’s party arrived. “It was unusually warm, in the high 70’s,” Portis wrote of the afternoon in a column for the paper. Among the attendees were various lords and cabinet ministers, the actor Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and of course the queen herself, in a “light blue dress and hat.”* The guests wandered the royal grounds drinking tea and lemonade and admiring the flowers and pink flamingos by the lake. Rather than mingle with the dignitaries, Portis spent his time neurotically fixated on his nose, which was clownishly swollen and singed red. “By holding my head down 10 or 15 degrees, the toasted place was not too noticeable,” he wrote, anticipating in a germinal way the kind of peculiar specificity and impassive humor that would become hallmarks of his fiction. “But that posture looked strange, and it made my eyes tired from looking up. I would just have to make the best of it.” Having spoken to no one, he eventually hailed a cab and went home.

It wasn’t long after the nose-burning incident that Portis decided to go home for good, all the way back to Arkansas. To say enough with London, celebrities, and newspapers. Tom Wolfe, with whom he’d shared a newsroom in the Tribune’s New York office, later wrote that “Portis quit cold one day; just like that, without a warning.” This was in a piece on the birth of the New Journalism, for which he cited Portis as forerunner and inspiration, in no small part for the sheer fortitude he demonstrated in actually leaving: “It was too goddamned perfect to be true, and yet there it was.” Portis would later deny having played a role in any such movement. “Mine, alas, was the old, dreary journalism,” he wrote to a reader. But his London writings, including the Buckingham Palace dispatch and even stranger fare—a piece on UFO culture, for instance, a topic that would recur in his fiction—suggest otherwise. Nora Ephron, whom he briefly dated in New York, wrote that he “was no good at all at writing the formulaic, voiceless, unbylined stories with strict line counts,” something that should come as no surprise to those familiar with his work, which is richly idiomatic and utterly distinctive.

Roy Reed framed Portis’s decision, which baffled him at the time (the “best newspaper job in the world,” Reed called it—a position once occupied by Karl Marx), as a conflict between impulses toward fiction and non-fiction. “One day, I think, the quarrel between the two parts of his mind became too much,” Reed wrote in his memoir. And so Portis “set off to spend the rest of his life just making it up.”

I moved to Arkansas because Atlanta was too hot, and my house there was infested with ants. There were probably other reasons, but these are the ones that have stuck with me most forcefully. I packed my car and drove all day and stayed for several years, though the car didn’t last very long—I wrecked it on an especially icy night that first winter, having never before driven in snow. I got a job at an alt-weekly newspaper, where I wrote stories about Arkansas for people who lived in Arkansas. I interviewed professional wrestlers, meth cooks, tow-truck drivers. I spent much of my time thinking about how I might sometime, eventually, when I got around to it, quit.

Quitting the paper, as Wolfe pointed out, has always been the most common and wonderful fantasy for journalists. It’s all the other projects you talk about finding time for in bars after work. It’s everything outside your window. An editor at the paper where I worked once quit to write fiction at a cheap lake house he’d found in a small town called Greers Ferry. His wife was a painter and they made do without internet; they just worked. I was awestruck. As Wolfe put it, shocked by Portis’s dedication to geographic isolation: “A fishing shack! In Arkansas!”

The late Paul Hemphill, a Southern newspaper legend who like Portis was born in the Thirties and left journalism in the Sixties to write books, wrote what is perhaps the definitive account of this foundational urge. He called his essay “Quitting the Paper,” and led with an epigraph from Hemingway: “Newspaper work will not harm a young writer and will help him if he gets out of it in time.” That “in time” is the tough part, though, because how do you know for sure when you’re there? Can you feel it in some physiological sense, when your mind goes and your writing begins to atrophy? Hemphill suggests you can, and goes even further. “Most of us are inviting suicide or alcoholism or early senility if we continue to labor for too long at a newspaper,” he writes, “thinking we are going to uncover corruption and change the system, because most newspapers themselves are tidy, model plantations.”

For Portis, then, it was simply time, time to quit the thing he’d always been best at and had nevertheless recently begun to despise. “I do not fool around with newspapers,” he’d have the narrator of his most famous novel, True Grit, say just a few years later. “The paper editors are great ones for reaping where they have not sown.”

I lived in Little Rock just off 17th Street, a few blocks away from Portis’s early home in the city—a place he referred to, obscurely, as “the house of abandoned neckties”—and I shared a more than slightly aspirational affinity with the writer who had, I liked to think, paid his dues in the same manner as I was then paying them. (It was during this time that I came across his London journalism, including the column about the queen, while digging around in the archives of local papers where he’d been syndicated.) The area, known as the Quapaw Quarter, was dotted with Victorian and Colonial Revival mansions built in the nineteenth century and long since divided up into cheap apartments. Nearby was Mount Holly Cemetery, where the Imagist poet John Gould Fletcher was buried in 1950. Portis lived in one of these huge, crumbling houses on 21st Street, right off Main, which used to be a thoroughfare and is now perpetually under construction, always on its way back. Farther up, there is a catfish restaurant that claims to have remained essentially unchanged for more than a century. It’s hard not to get hung up on history there, because everything in Little Rock is so transitional, incomplete both in its progress and in its decline. Nothing entirely succeeds, but nothing entirely fails either.

If Portis was not “our least-known great novelist,” as Ron Rosenbaum once claimed in Esquire, he was certainly among our least photographed. Remembered mostly as the author of True Grit—his only period piece, a western, something that can lead certain misguided fans to make a big show of setting it apart from the rest—he was, up until the time of his death in February 2020, typically grouped with such celebrated literary recluses as Cormac McCarthy, Thomas Pynchon, Harper Lee, and J. D. Salinger. Not as celebrated as these others, but all the more aggressively championed by his admirers on that account. He infamously allowed a New York Times reporter to fly down to Little Rock to interview him for a profile, only to declare the entire conversation off the record. The writer Paul Theroux once secured a meeting with him for his travelogue Deep South, and came away from the encounter with a single quote: “Be careful.” A decade ago, the British magazine The Spectator gave its review of one of his books the absurd and long-winded title, “There’s so much mystery around Charles Portis that we’re not even clear whether he’s alive.”

The cult-writer epithet, in truth, has begun to seem like a bit of a distraction, even an anachronism. It’s the sort of thing that can put people off the scent, most people being understandably wary of cults. Portis’s former colleague (and mine) Ernest Dumas said on the occasion of the author’s death that he had “an almost Jonestown-like following,” but of how many twentieth-century novelists (or novelists of any period) can this be said? And anyway, how many dedicated readers can be deemed sufficient to elevate one above this sort of designation these days? At what point, in other words, does a cult become a readership? Portis’s five novels have each been reissued more than once in my lifetime—to say nothing of the Coen Brothers’ 2010 adaptation of True Grit, nominated for ten Academy Awards—and now comes the canon-affirming Library of America collection, which comprises all five as well as a selection of the journalism and miscellany included in Escape Velocity, a 2012 anthology compiled by the Little Rock writer Jay Jennings, who has edited this volume as well. I’d say this would put the whole “cult” business to bed, but I tend to doubt it.

Portis was a commercial success from the very start of his career as a fiction writer. His first two novels, Norwood and True Grit, published in 1966 and 1968, were both serialized in the Saturday Evening Post and quickly adapted into Hollywood films (both starring Glen Campbell and Kim Darby, though the latter film is best remembered for winning John Wayne his only Oscar). The books mirror each other in certain ways—both involve a rambling quest from a small town (Ralph, Texas, and Yell County, Arkansas, respectively) to see about a grievance (a debt unpaid, a father murdered). The venture out and the return home: this was Portis’s own life’s arc, and it is his standard mode—the only exception being Masters of Atlantis, which can meander as a result, if pleasantly so. For the most part, his characters follow the “restlesse motions” described by Sir Thomas Browne in the epigraph to The Dog of the South: “He that would behold a very anomalous motion, may observe it in the Tortile and tiring stroaks of Gnatworms.”

And just as “recluse,” as Pynchon once said, can be code for “doesn’t like to talk to reporters,” so too can “cult writer” be code for “doesn’t live in New York.” After his fishing-shack sojourn, Little Rock would remain Portis’s home for the rest of his life—“as much as I can call anyplace home,” he clarified to a Memphis newspaper in a rare interview after True Grit’s release. “I guess I don’t really have one.” His regional association can confuse this point. In fact, Portis spent years living out of his truck, as well as in trailers and motels and non-descript apartment complexes. He spent a substantial portion of each year in Mexico. Even True Grit was written, he said, in a village about two hundred miles north of Mexico City; he seemed to consider San Miguel de Allende a kind of second home. His books are as much about being away from Arkansas as they are about being there. The Dog of the South and Gringos are both set predominantly south of the border, Norwood draws on his fish-out-of-water experience of living in New York (and traveling the country), and True Grit’s action takes place largely in the Choctaw Nation, present-day Oklahoma; it is a journey into the past and into historical research, his serious commitment to which is everywhere in evidence in the non-fiction pieces included in this book.

When he was in town, Portis could generally be found at the bar—the Faded Rose, say, or the Town Pump. I remember going to the latter and half expecting to see Portis on a stool, though he’d been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s the year before I arrived. I could only speculate, then, as to the autobiographical content of a sentence like this one, from The Dog of the South: “When the beer came, I dipped a finger in it and wet down each corner of the paper napkin to anchor it, so it would not come up with the mug each time and make me appear ridiculous.” I can imagine the sort of characters he’d meet at the Town Pump, though, because it is impossible not to meet them there. I recall one late night an older gentleman, in his cups long enough to have become despondent, seizing the karaoke mic to perform a warbling, truly moving rendition of Jack Greene’s country standard “Statue of a Fool” (“Somewhere there should be for all the world to see / A statue of a fool made of stone”). He removed the mic from its stand and stepped off the stage to walk among us in the barroom, still singing, with the affect of a Pentecostal minister.

I have called Masters of Atlantis an exception in the Portis oeuvre, but in the way of such things it is also a kind of skeleton key. The book chronicles the rise and fall of the Gnomon Society, based on its protagonist Lamar Jimmerson’s chance encounter, in France after the First World War, with a beggar who gives him a copy of the Codex Pappus, an allegedly ancient book that “had been sealed in an ivory casket in Atlantis many thousands of years ago, and committed to the waves on that terrible day when the rumbling began.” From this text, Jimmerson elaborates—with a great deal of imagination—a mystic worldview and belief system incorporating elements from Freemasonry, Hermeticism, Scientology, and any number of other similarly esoteric pursuits, many of which did flourish in this country in the middle-twentieth century.

“Mr. Portis has chosen to write about a subject that apparently does not interest him much,” wrote a New York Times critic when the book was published, but I’d contend that the opposite is true—all of his novels are suffused with references to secret societies and fraternal organizations, to “signs and wonders,” the Elks Lodge and the Kiwanis Club, Masons and UFO cults, VFW halls and meetings of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. “Everything is a cube,” repeats one character, cryptically, in Gringos. (“I don’t know what he had in mind,” the protagonist admits. “When you get right down to it everything is not a cube. You can look around and see that.”) Even the murdered father of True Grit’s Mattie Ross had been a Freemason, “buried in his Mason’s apron by the Danville lodge.”

One is constantly confronted, in Portis’s work, with the glories and horrors of the Old South—from the restless motions of de Soto and Cortés to the great battles of the Civil War and the Mexican Revolution, all the way through to the last generation to buy into Henry Grady’s vision of a New South, those men of industry and competence from the era preceding Portis’s own. “We are weaker than our fathers,” one of his characters (who has recently quit his job at a newspaper) says to his nemesis in a moment of despair. The old ways are always being contrasted with present-day American banality, with the encroachment of chintzy commercial culture even into the hinterlands. This flattening, atomizing force is what seemingly accounts for Portis’s preoccupation with Gnomon-esque guilds and other such flimsy attempts at restoring enchantment and community to a culture that has lost all meaningful trace of either.

“For more than a century now,” Portis wrote in a 1999 essay for The Atlantic (which was edited at the time by his old Gazette colleague William Whitworth), “southern editorial writers have been seeing portents in the night skies and proclaiming The End of the War, at Long Last, and the blessed if somewhat tardy arrival of The New South.” This term, he explained, they generally use “to mean something the same as, culturally identical with, at one with, the rest of the country.” He goes on: “Then there is the new and alien splendor to be seen all about us, in cities with tall, dark, and featureless glass towers.” His is a temperamentally conservative vision, in which youth culture—hippies and beatniks, “kids gone feral,” kids who never fought in a war and lack respect for their elders—is an absurd and pathetic sort of menace. Where this could easily become curmudgeonly or censorious in a less imaginative writer, however, Portis always seems bemused; the disappointment is too vast to be taken all that seriously, it is foregone and always cut with an instinctual swerve toward the comic. In a piece he wrote for the publication I worked for, the Arkansas Times, part travelogue and part historical meditation on the Ouachita River and its environs, he fails to learn anything of substance from even those youth who still live there: “The girl behind the bar knew nothing, which was all right,” he writes at one point. “You don’t expect young people to know river lore.”

Nor do you expect them to know even the most basic things a person of his age had known—proficiency in automobile maintenance, for instance, the importance of which to Portis’s sensibility I don’t have to speculate about and couldn’t possibly exaggerate. “You couldn’t trust a sixteen-year-old kid in the States these days to look after a goldfish,” one of his narrators laments. Portis had apprenticed at a Chevrolet dealership as a teenager, and was a lifelong shade-tree mechanic, like most of his protagonists—from Norwood Pratt to Jimmy Burns, with whom he shared a vehicle (a white Chevrolet truck). The Dog of the South, another road novel, contains fourteen references to its narrator’s transmission alone, and one chapter in Gringos opens with the indelible stoic maxim, “You put things off and then one morning you wake up and say—today I will change the oil in my truck.”

His family, he has said, were “talkers rather than readers or writers. A lot of cigar smoke and laughing when my father and his brothers got together. Long anecdotes. The spoken word.” He still remembered, when he wrote the Atlantic memoir, seeing his great-grandfather at family reunions, a man who had fought in an unofficial militia during the Civil War, like Rooster Cogburn, accused in True Grit of having fought with the guerrilla group Quantrill’s Raiders. That’s how close Portis was to this history—he had touched it and spoken to it.

A further word on True Grit: Portis’s mother was a frequent correspondent for local newspapers, and one of his early jobs in journalism was editing dispatches from older women in rural corners of the state—“country correspondence” from “lady stringers,” as he put it in an oral history of the Gazette. “My job was to edit out all the life and charm from these homely reports,” he said. “Some fine old country expression, or a nice turn of phrase—out they went. We probably thought we were doing the readers a favor.” True Grit, then, could be seen as a kind of offer in recompense, a tribute to these women and their stern elegance. The complexity of its narration is understated and can be missed. It is not simply, as Mattie Ross concludes, “my true account of how I avenged Frank Ross’s blood over in the Choctaw Nation when snow was on the ground.” It is an older woman’s inevitably warped memory of her childhood, injecting her mannerisms and intelligence into a younger self. “She isn’t as bright as the old lady makes her out,” as Portis said to the Memphis paper.

Of course, all of his narrators and protagonists are unreliable—except for his last, Gringos being the closest he came to realizing his dream of writing a Ross MacDonald noir—this is the source of much of their humor. And humor isn’t only a byproduct in his novels, it is their universal joint, their clutch assembly (to haphazardly borrow metaphors). As an antimodern, he responded to the new with weary cynicism and ecstatic embodiments of those pitiable, fascinating characters who can’t go along, who scheme and fail and scheme again to find a place in the order of things. His description of his family gatherings—“Long anecdotes. The spoken word”—can’t be bested as an account of his own work, which thrives on surreally precise digressions and long stretches of dialogue in which characters disregard or talk past one another.

This is especially true of a certain kind of secondary character he excelled at creating—the bloviating, irrepressibly self-interested (and self-regarding) showman, a term I’ll use in place of “con artist” because the degree to which they are aware of their own fabulations and delusions can vary, and might even be unimportant. In Norwood there is Grady Fring the Kredit King, who, aside from life insurance and trafficking in stolen goods, has

a good many business interests. I’m also in mobile homes and coin-operated machines. I am a licensed private investigator in three states. We have a debt collection agency in Texarkana. I know you’ve heard of our car lots over there.

In The Dog of the South there is the Demerol-addled, disgraced Dr. Reo Symes, whose life story threatens beautifully to overtake the book’s ostensible plot. As the narrator recounts, after one of Symes’s many soliloquies,

I learned that he had been dwelling in the shadows for several years. He had sold hi-lo shag carpet remnants and velvet paintings from the back of a truck in California. He had sold wide shoes by mail. . . . He had sold gladiola bulbs and vitamins for men and fat-melting pills and all-purpose hooks and hail-damaged pears. He had picked up small fees counseling veterans on how to fake chest pains so as to gain immediate admission to V.A. hospitals and a free week in bed. He had sold ranchettes in Colorado and unregistered securities in Arkansas.

(It is notoriously ill-advised to try and explain humor, so I will only pause and reiterate: hail-damaged pears.) In Masters of Atlantis, there is Austin Popper, who has a talking blue jay named Squanto and broadens the appeal of Gnomonism by removing much of its complexity (and triangles), before vanishing to perform fruitless alchemical experiments in the Colorado scrublands.

One of my earliest assignments in Little Rock was to cover a gala at the governor’s mansion that was being held in Portis’s honor. He wasn’t present, though autographed copies of his books were crudely auctioned off and a number of Arkansas politicians who seemed clearly and sometimes comically unfamiliar with his work spoke on his behalf. Last among them was the governor himself, Mike Beebe, who seemed at first unaware that an event was going to be held at his home at all. “I never met John Wayne,” he said when called upon to speak. “But I recently shared the stage with Jeff Bridges.”

Portis showed a particular attention, in his novels and non-fiction, to legacies and ruins. “These dead cities still lived and sparkled for him in the distance as they did not for me,” the narrator of Gringos admits. Later, looking at an assortment of ransacked monuments, he calls them “blank tombstones” and “memorials to nothing.” Two of his books involve mysterious trunks filled with material that might theoretically fill in the gaps of the misunderstood lives of their tragic owners. True Grit ends with the exhumation and relocation of a body, and with the installment of a newer, more fitting tombstone. Another character in Gringos announces, while trekking through the jungle:

I mean to lie down out here and die where I was happiest. Please don’t interfere. I will just lie down under the canopy of the trees. With my old empty heart. I will die and melt away and be with all the other forgotten things in the earth.

His brother Richard has spoken of another novel that was never published, something about a “chiropractor who has this psychiatric hospital somewhere outside of Veracruz.” What became of it? Maybe it’s locked away in a trunk somewhere. Failing its posthumous appearance, the Library of America collection is likely to stand as the “complete” Portis. I wish it had included some of the London journalism I came across all those years ago, but this is a minor quibble—no one could say it does not do justice to his writing life. Whether it will allow him to shake the “cult” qualifier remains to be seen.

One of my last assignments in Little Rock was to write about the death of a blind, homeless man who claimed to have been close friends with Yoko Ono. I visited a tent encampment behind a grocery store, where he had frequently stayed. The ground had recently been clear-cut and bulldozed—I could hear the sounds of distant chainsaws. Two men, former residents themselves, were sitting in lawn chairs on the edge of the field, watching the emptiness and destruction with blank expressions. I sat with them for a while. I asked, at a certain juncture, what they were doing there anyway, why they were watching this place that was now a hollow and would soon probably be a bank or self-storage units or a fast-food restaurant. “There’s nothing wrong with sittin’ right here,” one of them said calmly over the clatter, and the other nodded. “It’s peaceful, man.”

I thought then and think now that there wasn’t much Portis needed to invent about this place. A couple of weeks later I quit the paper finally and left Arkansas for good.