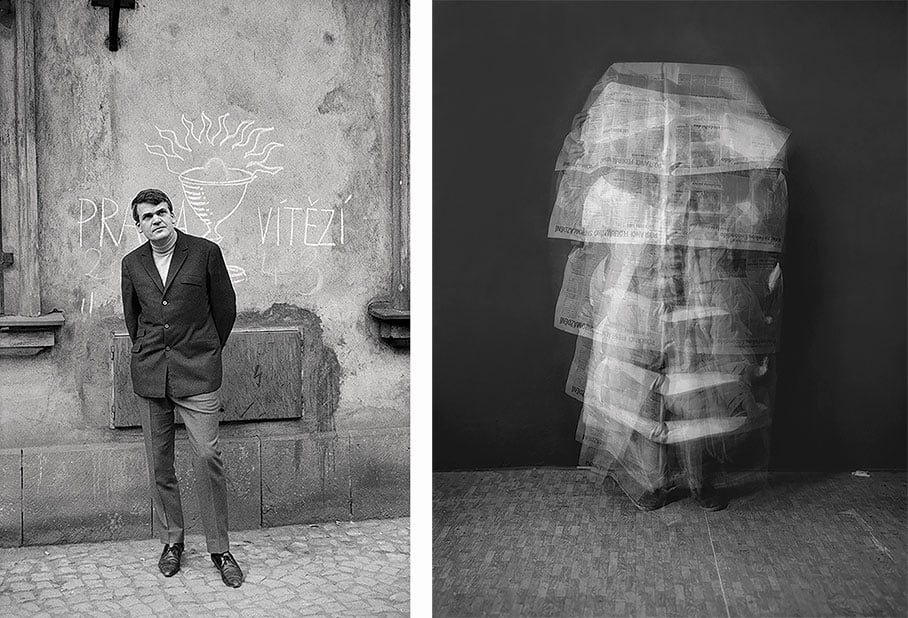

Left: “Milan Kundera, Prague, 1969,” by Gisèle Freund © The artist. IMEC/Fonds MCC/Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York City. Courtesy Galerie Franz Swetec, Düsseldorf. Right: “Rising of Rudé právo,” by Pavel Baňka © The artist. Courtesy Cermak Eisenkraft Gallery, Prague

Revision is the act of reworking something—an idea, a text—in an effort to improve it. It means to look again; in some instances, it may be the surrounding world that has altered. A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe (Harper, $24.99) is comprised of two historical texts by Milan Kundera, with contextual introductions by two distinguished French scholars. “The Literature of Small Nations,” translated from the Czech into French by Martin Daneš and then into English by Linda Asher, is a rousing speech that Kundera delivered to the Czech writers’ congress in 1967, the year before the Prague Spring. He was already celebrated in his native Czechoslovakia; his novel The Joke, published earlier that year, “both evoked an era and ended it,” as the political scientist Jacques Rupnik writes in his introduction. Kundera focuses on the role of Czech artists during the great cultural flourishing of the Sixties. He mentions Vera Chytilová, whose film Daisies he has just seen; the novels of Bohumil Hrabal; and the plays of Václav Havel. It’s an extraordinary moment by any standard, but particularly in a nation that had been nearly overwhelmed by German-speaking culture a century earlier. Kundera defends his homeland by arguing that it is—that he is—European, as in cosmopolitan, and laments the suppression of ideas: “If today our arts are thriving, it is thanks to the advances in freedom of thought.”

The speech is paired with an article, initially published in 1983 in the now defunct journal Le Débat, and translated from the French by Edmund White, in which Kundera identifies “the tragedy of Central Europe” as its bifurcation. It understands itself as “the eastern border of the West,” and yet it is “sensitive to the dangers of Russian might.” By this time Kundera, who moved to France in 1975 and became a citizen six years later, was writing in French and noticed “with a certain astonishment” that he didn’t feel “deprived” of Prague, as he told the New York Times in 1984. He had transformed from a Czech writer into a French one, but remained committed to Central Europe as a cultural force. The region represents “the greatest variety within the smallest space,” whereas Russia is a nation founded “on the opposite principle: the smallest variety within the greatest space,” and longs to expand. Kundera argues that Central Europe is the continent’s lost “cultural home,” having produced Sigmund Freud, Edmund Husserl, and Franz Kafka (all Jewish, he notes: “What are the Jews if not . . . the small nation par excellence?”), as well as Hermann Broch and Robert Musil. As Europe no longer considers itself “a cultural unity,” but rather an economic and governmental one, Central Europe becomes “nothing but a political regime.” Czechoslovakia and its neighbors are then classified as part of Eastern Europe. It’s almost as though Central European countries have to keep auditioning for a role they already hold.

These two statements, delivered sixteen years apart, represent a compelling and coherent worldview: a defense of the small cultures of Central Europe, and an insistence on their importance to Western Europe. The later essay, the historian Pierre Nora writes in his introduction, “played a decisive role in the formation of French intellectuals” in the Eighties and Nineties and may have encouraged the eastward expansion of the European Union. Both the speech and the article continue to offer insight into contemporary debates, but there is much here with which one might disagree. Kundera, though staunchly Eurocentric, acknowledges that “in Central European revolts there is something conservative, nearly anachronistic: they are desperately trying to restore the past . . . the past of the modern era.” But we should welcome the context he gives for the struggles between Russia and Europe, and the plight of those caught between them. His defense of small languages, small cultures, and small nations feels pressing.

Photograph of a bedroom in the Marcel Proust Museum © Masha Pryven/akg-images

Marcel Proust might well be the exemplar of Kundera’s “past of the modern era”: the excitement with which scholars continue to pore over his work seems an exhilarating vestige of a time when literature mattered. The Seventy-Five Folios and Other Unpublished Manuscripts (Belknap, $29.95),now available in a fine translation by Sam Taylor, marks a major discovery in the field of Proust studies. Nathalie Mauriac Dyer, a Proust scholar and the great-granddaughter of Marcel’s brother, Robert, edited the book and provides compelling commentary throughout.

The French publisher Bernard de Fallois claimed in 1954 to have read these early drafts of In Search of Lost Time, but they remained unseen until his death in 2018. The folios published in Paris three years later represent the first pages of the major twentieth-century novel, Jean-Yves Tadié writes in the preface, “even if they are the last to reach us.” Dating from 1907, they include initial versions, “at once strange and familiar,” of essential scenes and themes from the book, among them Maman’s goodnight kiss, the two paths from the village of Combray (Swann’s way and the Guermantes way, which we learn was first called the Villebon), and the narrator’s fascination with the girls at the seaside. Proust refers to his mother and his grandmother by their names, Jeanne and Adèle, confirming suspicions about the novel’s autobiographical material. Moreover, the character of Charles Swann doesn’t yet exist, though we can see the source in Proust’s maternal great-uncle, Lazard Baruch Weil, who wasn’t Jewish in the original version. “Proust was no more likely to write about a Jewish family from the French bourgeoisie than he was to give his hero his own sexual preferences,” Mauriac Dyer explains. Writing during a time when anti-Semitic sentiment in France was high, Proust chose to make a friend of the narrator’s family Jewish, rather than his own family.

For those interested in understanding Proust’s masterpiece in its social, historical, or autobiographical context, this book is indispensable, and raises questions about the constraints of the period, and how Proust’s queerness and Jewishness have been treated. For those interested in the process of literary revision, the folios are equally interesting: we can see how two characters merge into one over time; how Marcel’s bedroom was initially described as “hostile” during the goodnight kiss scene, and how this adjective would ultimately attach itself to the hotel room at Balbec, the bedroom becoming a “banal, familiar place.” Comparing the folios to the published version as well as other drafts illuminates the processes of synthesis, transference, and accretion that ultimately transform a series of events into Proust’s narrative. The folios “belong to the novel, even if they are not yet ‘a’ novel,” Mauriac Dyer writes. The “highly organized system of preparations and echoes, rhymes and reminders,” that structure In Search of Lost Time “was the result of about fifteen years of patient composition.”

Though they can’t offer the contrapuntal pleasures of the seven-volume book, you can get a sense here of the whole. In one of the drafts, Marcel’s younger brother has gone missing before a portrait session and is found “tenderly caressing” his pet goat “with one hand, kissing it on its pure and slightly red nose, like some small, horned, blotchy-faced dandy.” Along the river path of Swann’s way is a big lilac bush “in its flower bed where it would exaggeratedly and endlessly shiver at the slightest breath of wind, showing off the great distinction of its manners.” At the hotel in Balbec, he recalls one girl he yearned to befriend. She has

long red hair that floated in the wind behind her, and a hat in the form of a seagull with wings outstretched, which seemed to be just as much a part of her person as her pure nose or her pale eyes that stared as she rode past, but the way the eyes of a seagull might stare into ours, without the slightest awareness of us.

Even in these early sketches, his prose dazzles and thrills, by turns depicting recognition and wonder, sometimes overdone but always with the precise intelligence, meditation, and humor for which Proust is renowned.

Lilac Bush, 1889, by Vincent Van Gogh. Courtesy the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Ever urbane, Proust attends to style, and creates of it, as in the description above, significance: the girl’s hat resembles a seagull’s wings, her eyes a bird’s eyes, thus she appears to the reader soaring and cold. As the London-based psychoanalyst Anouchka Grose says in her delicious and substantive new book Fashion: A Manifesto (Notting Hill Editions, $21.95), “your clothes are basically a form of externalised, visible thinking.” What you choose to wear is a way of projecting your persona onto the outside world, though “fashion repeatedly teaches us that you can’t please all people all of the time . . . Whatever you wear, someone will always hate you for it. Even if that person is just you.”

Grose’s wry tone makes her manifesto a joy, but this small book (enticingly produced, with pink cloth covers) has a serious intent. In light of fashion’s egregious role in the climate emergency, Grose wants to change our approach—to revise it—so that we may retain our abiding joy in clothes without further destroying the planet. Within the first paragraph, she lays out several bleak facts. “The clothing industry accounts for 10 per cent of the world’s carbon emissions, while flying contributes a mere 2.4 per cent,” she writes. “Clothing production is also responsible for 20 per cent of the world’s wastewater.” But how can we reconcile this with memories of “days when the seasonal influx of new shapes, colours and textures into the luminous paradises of H&M, Topshop and Miss Selfridge seemed a cause for celebration and joy”?

Grose proceeds to demystify fashion, beginning with theories of its origins (chief among them an anxious aristocracy attempting to distinguish itself from urbanizing lower classes). She also addresses the competition, desire, and paranoia that “flummox us into submission” when we choose what to wear. She casually (and lucidly) brings together Jacques Lacan and horror films, Georges Bataille and Marie Kondo. She points out things you may not have realized you knew: in the past, “thanks to the restrictions placed on women’s agency, fashion became a space in which one could distinguish oneself, or even innovate, without threatening the social order.” The status quo wasn’t just unaffected, it was reinforced. If fashion was “an arena in which women were allowed to show off, then it also meant that men could show off their women.” A woman’s “cinched waists, crinolines, hobble skirts or uncomfortable shoes” were symbols of the bind she was in.

But what is the message of her manifesto? How should the fashion landscape be revised? She doesn’t quite answer this question. Eager not to “recast the symptoms,” she claims to offer a “new, non-bossy kind” of manifesto. For the reader who has long kept an eye on trends, this may feel like being released into the wild. Grose’s final chapter suggests that the solution to the crisis is to encourage individual choice and reject Big Fashion. No absolutes exist in her merciful vision, except for “no red vinyl” (prescriptive, but correct). “Let your clothes be chatty and comfortable, whatever comfort means to you. Affirm your own sartorial sovereignty. Challenge everything,” she advises. And crucially, understand that “the future of fashion is already in your wardrobe.”

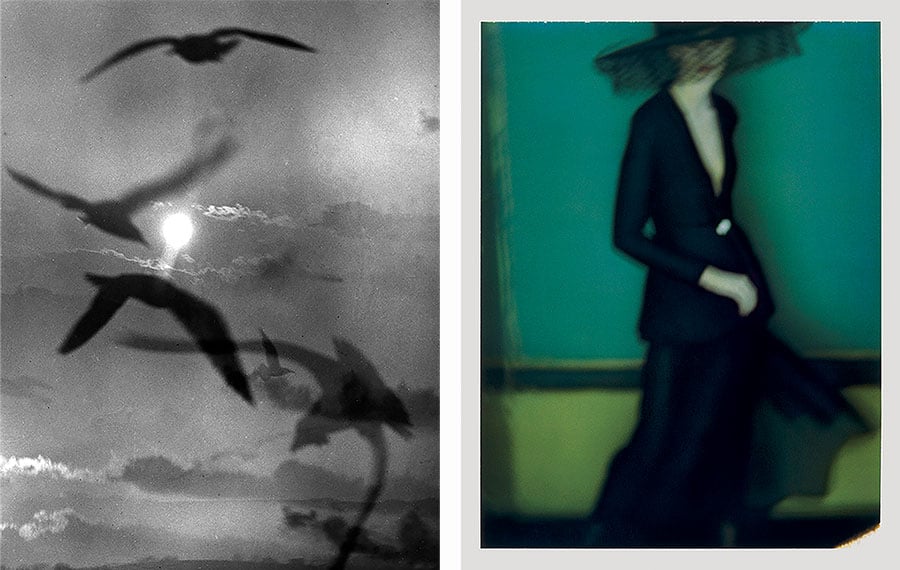

Left: “I leave my wings…,” by Mario Giacomelli © Simone Giacomelli. Courtesy of Mario Giacomelli Archive Right: “Fashion 10, for the New York Times, 1997,” by Sarah Moon © The artist