Take the Medicine to the White Man

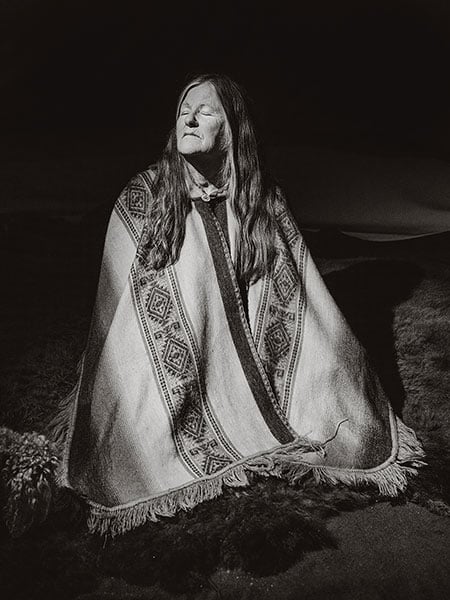

Linda Stone holding sliced peyote. All photographs from Utah, March and April 2023, by Devin Oktar Yalkin for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

Take the Medicine to the White Man

We were in a canyon trying to articulate why we were in the canyon. It was June in Utah, amid a range of mountains that had seen a blessed amount of rain so far that summer. Balsamroot flowers nodded their heads all around the gray nylon tent in which we had gathered for shade. We were a group of eight including our two leaders, Linda Stone—a “medicine woman,” she called herself—and her son, Gent, short for Jeff “Gentle Eagle.” Linda, who was seventy-five years old, and white, was sitting cross-legged on a cot. She was short and strong, with a leathery tan and extraordinarily thick, long hair—brown except for two streaks of white framing her face like curtains.

“I want you to really drop in,” she was saying, drawing down on the word “really” to illustrate how deep inside ourselves she expected us to go. She said it was time that we settled on our “intentions.” That afternoon, we would each be placed alone somewhere in the canyon, and there we would fast and pray on a vision quest. After three nights, we would dust ourselves off in a sweat lodge and conclude our spiritual journey with an all-night peyote ceremony. If we were to glean anything from this experience, Linda had instructed us, it was essential that we each set an intention, but I had been in the canyon for three days already and felt little more clarity than when I’d arrived.

“How do we talk to a spirit?” a participant named Sofia* had asked on the first day, seemingly as confused as I was.

“How are you talking to me right now?” Linda replied.

“But you talk to a spirit and they talk back? Is there one Great Spirit or many spirits we could talk to?”

Linda shrugged. “For me it changes day to day.”

I’d known the group since the prior December, when I’d enrolled in a “medicine person” training program offered by the Sacred Wisdom Circle Institute (SWCI), which Linda and Gent founded in 2017. The rituals we’d partake in this week were but a few of those required for certification from the institute, a process that was supposed to take, at minimum, four years. Most Thursday and Sunday evenings for six months, I’d joined the group’s discussion-based classes via conference call, and in Utah I’d finally met the students I’d come to know by voice. Sofia and Alexandra had traveled together from New York; Thad from Oregon. Miriam and Gavin were both from Utah. All of us were white, and all of us in our thirties or forties except for Gavin, who was twenty-one. He’d attended his first peyote ceremony that winter with Linda and loved “the authenticity,” he told me, by which he meant the way he’d felt he was engaging in a real Native American ritual. Now, in the tent amid the balsamroot, he sipped water from a repurposed bubble tea cup as Linda guided him in clarifying his intention.

“What was your animal card?” she asked. The night of our arrival, Linda had produced a stack of folders, each one containing a photocopy of a hand-drawn animal and some attendant guidance as to how its spirit could influence our lives. I had picked the bear. “Bear seeks . . . the sweetness of truth,” the card read.

“I got the lion,” Gavin said, then corrected himself: “No, the antelope!”

“Interesting,” said Gent, lifting his chin thoughtfully. “The lion eats the antelope.”

Opportunities to experience vaguely Indigenous rites of passage are abundant, but the Sacred Wisdom Circle Institute is unusual. It claims affiliation with the Native American Church, one of the largest and most influential pan-tribal organizations of the past century and the home of peyote religion. Though there are some ambiguities in federal law, members of the NAC are generally considered to be the only people in the country who can legally possess and ingest peyote.

In recent years, as American interest in psychedelics has risen, the use of psychoactive plants traditionally employed in spiritual practices—or entheogens—has soared. According to a recent national survey, use of these substances, which include psilocybin, ayahuasca, kambo, and mescaline, increased by 95 percent between 2015 and 2019. Mescaline is found in two cacti: San Pedro, used by the Chavin people in the Andes Mountains as early as 1000 bc, and peyote, which has been sacred to the Huichol in what is now Mexico since at least the sixteenth century. Peyote made its way into North America in the mid-nineteenth century, and first gained popularity among non-Indigenous people in the 1960s. As of 2015, 2 percent of Americans age twelve or over had tried the substance at least once. In 2019, the city of Oakland, California, instructed law enforcement to deprioritize prosecutions for the possession of peyote—among other psychoactive plants and fungi—and an organization called Decriminalize Nature has opened chapters in most states to spur similar initiatives.

I’d first learned of the Native American Church in the years I spent working as a reporter in Native communities. It was founded in 1918 in Oklahoma by Kiowa, Comanche, Caddo, and other Native leaders to take a stand against federal laws that banned tribal ceremonies. Over the next century it grew to include hundreds of chapters and hundreds of thousands of congregants. In 1970, when President Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act, peyote became the only Schedule I substance for which the government granted a religious exemption. I had the impression that the NAC was open exclusively to Native people enrolled in or descending from recognized tribes. But a few years ago I came across a photograph online of a white acquaintance posing with another white man who went by the name George “Gray Eagle” Bertelstein. Bertelstein facilitated peyote ceremonies in the Bay Area, and his organization, which he called a Native American Church, had been founded, according to his website, with a “blessing from Okleveuaha.”

I learned that Oklevueha, as it is usually spelled, was a group formed in the Nineties by a man named James “Flaming Eagle” Mooney, who claims descent from the Seminole people in Florida and professes to be on a mission to “take the medicine to the white man.” Mooney met Linda Stone in 1988 when he was forty-four years old and struggling with bipolar disorder, and had recently lost his wife to cancer. He became homeless soon after, and Linda, who often took in people in need, offered him a room in her house. That spring, she brought him to a long dance—a New Age ceremony that borrows from Indigenous practices—in the canyonlands. There, according to the Oklevueha website, four days of dancing and sweat lodges awoke “suppressed memories” from Mooney’s childhood, most notably that he himself was Native American. Around the same time, Mooney claims, he received a call from a woman who identified herself as Little Dove. Little Dove said she was the chief of a band of Yamasee Seminoles in Florida called Oklevueha, and that she was searching for descendants of her tribe. She believed that Mooney was descended from both a nineteenth-century Seminole leader, Osceola, and another James Mooney—a white ethnologist who at the turn of that century documented peyote ceremonies among the Kiowa in what would become Oklahoma, and who had testified in Congress in defense of the peyote religion. (Little Dove appears to have been a real person, also named Betty Buford, who died in 1994, and she did in fact seek recognition for a band called Oklevueha.)

Armed with his new ancestral claims and curious about peyote, Mooney found a “roadman”—someone who facilitates NAC peyote ceremonies—from the Indian Peaks Band of Paiutes in Utah, who, according to Mooney, offered to train him to lead the ritual himself. By the mid-Nineties, Mooney, who says that the medicine cured his bipolar disorder, was hosting regular gatherings attended mostly by white participants, and in 1997 he registered the Oklevueha Earthwalks Native American Church (ONAC) with the state of Utah. Mooney issued Linda one of the first membership cards, and the church became her “family,” she later told me. According to Oklevueha’s own materials, the group went on to spawn hundreds of branches; in my research, I located roughly eighty.

The proliferation of the organization was due in large part to the group’s claim that membership granted legally protected use of peyote, as well as, as the years went on, ayahuasca, psilocybin, San Pedro, cannabis, and more. But ONAC, whose leaders and congregants were overwhelmingly white, was related to the NAC in name only. And NAC leaders from around the country were explicit that the church’s only sacrament was peyote. (The NAC is not a single unified organization but is helmed by four major bodies, the leaders of which form a governing council.) Mooney claimed that he had sought the blessing of a respected Lakota roadman, Leslie Fool Bull, and that Fool Bull, as he lay dying in a hospital in South Dakota, had scribbled his anointing on a paper napkin. Members of Fool Bull’s family, however, refute this story.

In 2000, Mooney and his second wife, also named Linda, were raided by state deputies and found to be in possession of twelve thousand peyote buttons—the pin-cushion-shaped tops of the cacti. Investigators who contacted the Seminole tribe were informed that no records existed supporting Mooney’s membership nor his descent. He was indicted on twelve drug felonies and one count of racketeering—for having “devised a business and a down-line of ‘medicine men’ to distribute peyote . . . to non-Indians.” In 2004, the Utah Supreme Court dismissed the case, finding that all members of the Native American Church were exempt from such charges, without addressing the question of Oklevueha’s relationship to the real NAC, and bypassing the 1994 amendments to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), which specified that peyote use was permitted only “by an Indian for bona fide traditional ceremonial purposes” and defined an “Indian” as a member of a federally recognized tribe. Instead, the court interpreted the 1970 exemption to the Controlled Substances Act in a way that appeared to create a loophole allowing anyone to register a “Native American Church” and receive federal protection.

With Mooney’s win, Oklevueha members became the only non-Native people in the country legally permitted to possess peyote. But this protection was exclusive to Utah, and two years later the state updated its statutes to refute the ruling, articulating that only Native people qualified for the religious exemption. However, no case has been brought against the group in the state, and Oklevueha has continued to grow, despite complaints from the NAC. In 2016, the chairman of the Native American Church of North America (NACNA), Sandor Iron Rope, issued a statement with other NAC leaders condemning “the proliferation of organizations appropriating the ’Native American Church’ name,” while Native people had been “jailed, put in insane asylums and killed” for practicing their own ceremonies. Another NAC leader denounced Mooney for “making a mockery” of the religion. One Oklevueha branch was offering “cuddle parties”; another advertised workshops led by an “orgasmic oracle.” In 2016, a woman in Arizona was convicted of prostitution, among other charges, for running a brothel under the guise of the church. Registering an Oklevueha branch is as simple as paying a fee of roughly $2,500. A lifetime membership for an individual costs $250 and entitles you to a card, signed by James or Linda Mooney, declaring that you are “qualified to carry, possess (in amounts appropriate for individual consumption), and/or use Native American Sacraments.”

Provo Peak

My research on James Mooney led me to Linda Stone and the SWCI. SWCI participants had signed up for a years-long training program, apparently wanting something more than access to peyote. They wanted to be deemed spiritual facilitators—but by an organization that had exploited a federal law hard-won by Indigenous leaders. I personally had no interest in becoming a “medicine person.” But I wanted to understand what such a group, with no true ties to Native culture, could offer its participants. “You are about to embark on a path of growth, devotion, and mystery,” the title card of the first lesson read. “You will soon be stepping into an energy matrix that is very powerful, so do not allow yourself to get overwhelmed.”

Gent, who I learned had a doctorate in biomedical sciences, with a specialization in immunology and virology, led our lessons. There was a dreamy, soothing quality to his voice, while Linda, who stepped in occasionally, was comparatively strident. She drilled us on readings and called on us unexpectedly, sounding thrilled by correct answers and bored by misses. She seemed to know a lot about the other participants—who numbered between three and ten on any given call—asking after their health, legal troubles, and relationships. She lent personalized advice for the vision quest, instructing one man to leave his knife behind as a challenge to his hero complex.

“Do you have any advice for me?” I had finally asked.

“I don’t know anything about you,” Linda replied, and gave me her number.

She was driving when I called her from my home in Oregon a few weeks later. I told her I was struggling to set my intention for the quest. “Sweetheart,” she said pityingly. “What do you want right now?”

I took a deep breath. “Calm,” I said. “I just want to feel like I can deal with all the things that come my way and not be overwhelmed.” I’d been unmoored by uncertainty, writing a second book while hustling my first, starting a relationship while recovering from a breakup, feeling old with new maladies, wanting children, peering into the lightless tunnel of my bank account as houses near my rental sold for double what I could pay.

Linda sounded unimpressed. “Calm” was not big enough for a vision quest, she said. “I want you to reach for the sky. Tell me, what do you want?”

What was bigger than being capable of handling anything? I wondered. “I could say I want a house and a garden, but—”

“Why don’t you think you can ask for that?”

I told her I thought a vision quest was about concerns more spiritual than material.

“Nope,” Linda said. “You’ve got to have it all, sweetheart. Honest to God, having a piece of land and a garden—that’s spiritual. . . . Your intention will change, but I only want it to get bigger, not smaller.” I heard a clanging of pots and gathered she had arrived home. “If you have another question, call me.”

The next time I spoke to Linda was in June, when she picked me up at the Salt Lake City airport. She moved garden supplies out of the passenger seat of her Prius, and we drove north through a hot, dull haze toward the Bear River Mountains, where Gent was setting up camp. Linda had been raised in the Pacific Northwest, by parents who drank and fought, and her father had begun molesting her when she was ten. She had found refuge in Mormonism. “The church was morals, connection, a place to belong,” she told me. “When you have nothing, it becomes a source of stability.” But by the time she met Mooney, she was seeking a new spiritual community and had met some white people who practiced nominally Indigenous traditions. She remembered the first vision quest she and Mooney attended, arranged by a white psychiatrist. The psychiatrist, seeming to have invented his own ritual, had asked Mooney to bury himself up to his neck in a hole in the ground. In 2005, Linda opened her own Oklevueha branch and began to run peyote ceremonies in her backyard.

Stone

She had some Native blood, she told me, from a grandmother who descended from the Illini, a tribal confederation from the Mississippi River Valley that today is known as the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma. But she said she believed that anyone committed to a spiritual life should have the ability to become a medicine person. (She later said that anyone committed to a spiritual life was a medicine person.) “A lot of Native people like what we’re doing, and a lot don’t,” she said as we neared the mountains. “But it’s in the prophesies that the white people would adopt the Native religion.”

“Whose prophecies are those?” I asked. “And, like, one Native religion or all Native religions?”

“They’re in a book,” she said. “I’ll find it for you.”

She never did produce the book, but I wondered if the “prophecies” had come from the Book of the Hopi, published in 1963, in which the writer Frank Waters, whose father was part Cheyenne, reinterpreted visions shared with him by Pueblo and Diné elders and concluded that the world was in the midst of a transition from “ruthless materialism and imperialistic will” to a new consciousness of the “wholeness of all Creation.” Although billed as an ethnography, the book collapsed boundaries between Puebloan, Diné, Aztec, Mayan, Buddhist, Tantric, and Christian religions to reveal their synchronicities, and triggered a surge of popular works about Native American spirituality written primarily by white authors and peddled to white readers, bolstering the idea of Native people as keepers of mystical knowledge. The early Seventies saw the rise of “plastic medicine men,” as critics called them, both Native and imposter, who hosted ceremonies of various kinds for non-Indigenous people, often adapted to white fantasies. They also charged fees, a taboo in Native circles. Vine Deloria Jr., the prominent Lakota scholar, argued that these medicine men were altering and cheapening valuable traditions. As for the white participants, he wrote, “The hunger for some kind of religious experience is so great that whites show no critical analysis when approaching alleged Indian religious figures.”

The SWCI weekly readings were peppered with references to the Indian mystics of popular literature. The lessons revolved around the “medicine wheel,” an ancient compass-like symbol featured in various Native cultures and brought to the mainstream by Charles Storm, a son of a German immigrant who claimed descent from multiple tribes, in his 1972 book Seven Arrows. (Storm published under the name Hyemeyohsts, which he said was his Cheyenne name.) The wheel is now an omnipresent and polysemous symbol of not only New Age interpretations of Native religions but also pan-Indian ideology. In Linda and Gent’s classes, the cardinal directions divided the wheel into quadrants representing the four seasons. Because I had enrolled in the wintertime, I had “entered” through the “North Gate,” a time to learn the wisdom of ancestors “real or mythic.” In the spring I arrived at the East Gate, which was a period of rebirth.

Our lessons leapt from rare mentions of Lakota rituals to astrology to paganism to Toltec beliefs, giving me the feeling of having been plunged into a self-help soup. One week we were assigned an exercise called “the random bell,” in which whenever we saw “The bell has rung!” in the text in front of us, we were to stop and, for thirty seconds, pay close attention to what was happening in our bodies. A student named Michelle said she knew of a similar practice in Buddhism in which one imagines the current moment as the last of their life.

“Right,” Gent had said. “The Lakota have a saying, ‘Hoka hey’: ‘It’s a good day to die.’ Any day you could pass on, so live this day as if it’s your last.”

This was a common misinterpretation of words said to be spoken by Crazy Horse. In fact, “Hoka hey” means something like “Let’s roll.”

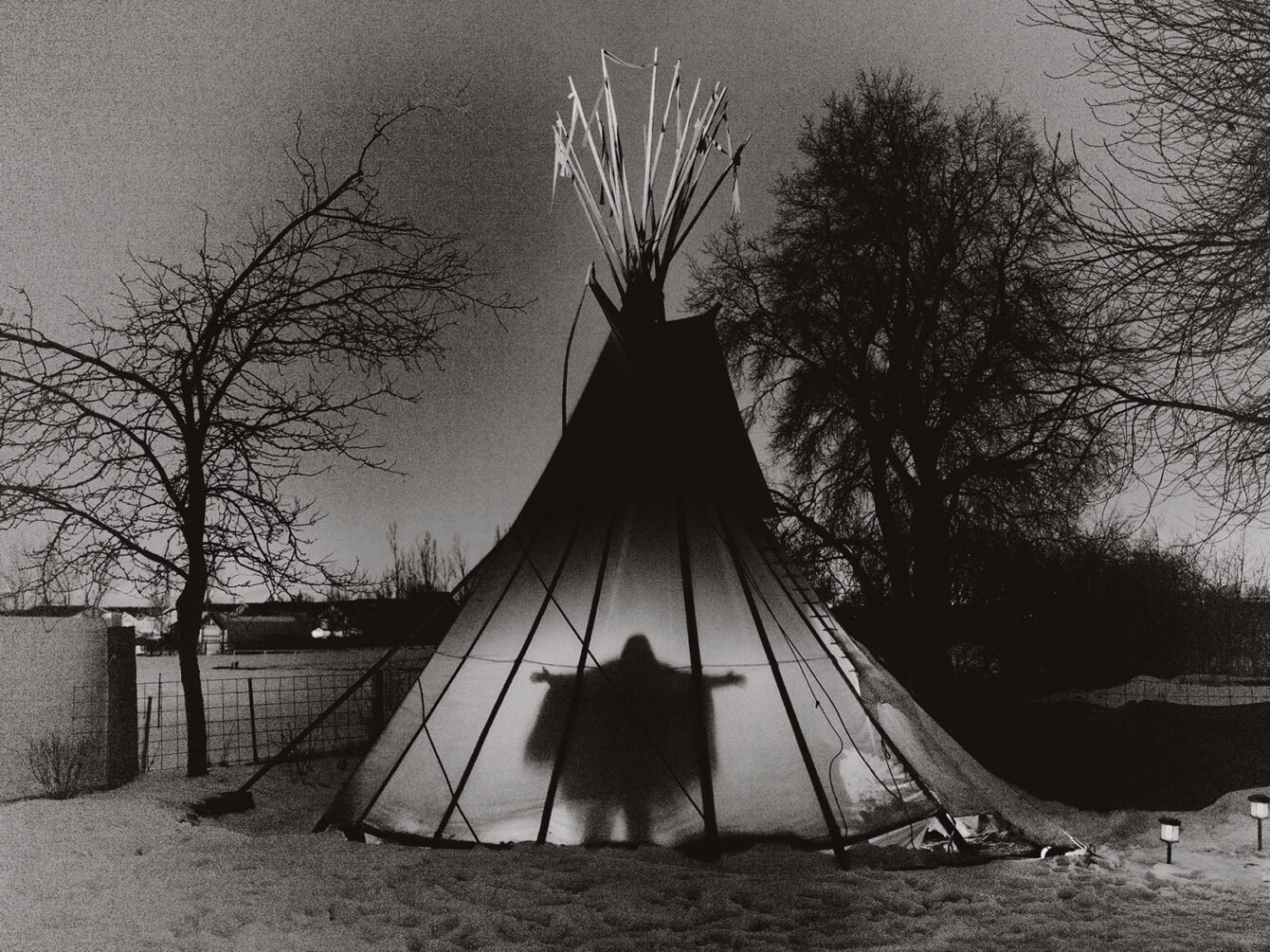

Stone in a tepee

We made camp some rutted miles up a Forest Service road, by a creek in the canyon. Gent had brought a tent for each of us and assembled a makeshift kitchen, and when I arrived that first evening I found Thad seated on a tub of dry goods, reading a book about Carl Jung. “It’s clear Jung was a shaman,” he said. I knew only a little about the psychoanalyst—that his mysticism was partly inspired by his visits to the Pueblos in the Twenties, and that his ideas about the unconscious made him something of an icon of the psychedelic movement. Thad practiced psilocybin therapy, which he hoped to incorporate into his life-coaching business. He’d joined the medicine person certification program after seeing Gent speak at a Portland Psychedelic Society conference in 2019. He was wearing a T-shirt from the conference, Gent’s name printed simply as “Gentle Eagle” on the back.

At breakfast the next morning, it became clear that most of my companions had more experience with the psychoactives often called plant medicines than with Native American rituals. Miriam, a petite lapsed Mormon in her forties, had been connected to Linda through a friend, who had seemed to vanquish her own intense anxiety. “One day she just totally changed, and I was like, ‘I want some of that,’ ” Miriam told me as I spooned raw honey from a Ball jar onto my yogurt. Miriam had invited Linda to host peyote ceremonies in the basement of her house, and a year later she erected a tepee in her backyard for the same purpose. That was where Gavin, the youngest in our group, had met Linda. He’d left the Mormon church three years earlier when he came out as gay, and he was still struggling with depression and low self-esteem. The peyote was helping, he said.

Alexandra and Sofia, the women from New York, would be trying peyote for the first time. Alexandra was an ICU nurse on Long Island, and at the start of the pandemic, amid all the death, she’d felt like she was dying herself. She’d attended an ayahuasca ceremony hosted by an Oklevueha branch, where in visions she witnessed her own possible happiness. Now she referred to Oklevueha as “my church.”

“I don’t like calling ONAC a church,” Linda cut in. “A church is dogmatic. It tells you what to do and how to do it.” I thought I noticed annoyance flicker across Gent’s face.

After breakfast, Gent led us up the hill from the creek past a grove of aspens to sit and talk about our intentions. I’d made little progress toward setting mine and felt an urge to light off into the woods. Alexandra went first, her eyes pointed at the ground. She had married young, she said, because she “wanted to feel important,” but her husband was addicted to heroin and died in a motorcycle accident a few years into their marriage. Years after his death, she fell asleep while driving, but woke when she heard the sound of him yelling her name. She believed that he’d saved her life, and she understood that he wanted her to be happy. She’d been trying but couldn’t figure out how.

As she spoke, my urge to disappear vanished. Now I wanted to be here with her, for her, and when it was my turn, my words came out in a stampede of feeling. I said I’d been confronting renewed grief over a relationship I’d thought I’d grieved already. It was back, angry this time. My eyes watered, and I could sense Linda watching me intently from across the circle. I avoided looking at her. “Drop down,” I heard her say. She seemed to be commanding me to cry. I felt a momentary desire to dissolve for her, to let her comfort me, then stopped myself. Was this how cults were made—I show her my cracks so she can pry them open wider? I breathed, pushing my grief back into my body.

“See how you stuffed your feelings with your breath?” she said.

Linda led the group next in an exercise from Gestalt psychology, setting two chairs facing each other and instructing Miriam to speak from one as her child self and the other as her adult self. Miriam sprang gamely into the child chair. I knew from our weekly calls that she had lost faith in her “mother’s God.” Her mother, who was Mormon, had increasingly come to believe the world was ending and the rapture approaching. Now, from her child chair, Miriam began to speak of the loneliness she had felt, unsafe among her mother’s beliefs. Within a few minutes she was shrieking and sobbing, the imaginary adult-self opposite her having evidently merged into the visage of her mother. For more than an hour, Miriam implored her mother to love her, and Linda commanded her to switch places whenever she lost momentum. Miriam’s anger was so immense it seemed to swell around us. I was disturbed, then mesmerized, and then I lost control myself. I cried until Miriam finished.

That night, I hardly slept, waking every few hours to pee. In the late morning, I noticed that I’d been speckling the leaf litter with blood.

“This is telling you something,” Gent said when I pulled him aside. “The only thing we have control over is our choices.” Then he asked if I had health insurance and handed me his car keys, adding, “UTIs are no joke.”

When I returned hours later with my antibiotics, the others were already gone. Gent led me into a small nylon tent draped with wool blankets and, handing me a pipe, directed me to place a pinch of tobacco in its red-stone bowl. As I raised the pipe and Gent fanned me with an eagle wing, it occurred to me that this was the first time since my arrival in Utah that I’d engaged in a ritual at all resembling ones I’d experienced with real Native people. Then Gent picked up a drum and sang a Lakota song, his voice more melodic and controlled—more self-conscious, I thought—than the voices of Native people I’d heard sing songs like this before. Silently, he led me out of the tent, and, half a mile up the canyon, left me on a hillside under a maple tree. I was exhausted, grateful to be alone. I sat still until night fell, wondering where and how Gent had learned that song.

A pipe (left) and an eagle wing (right) used in ceremonies

For three days and nights, a feathery calm fell over me. I woke each morning with the sun and, in the evenings, watched the daylight slip off a cliff band to the west. The hillside was too slanted to sleep comfortably, so I threaded downed branches through the spindly trunks of the maple, fashioning a flat bridge from the slope to the tree. From there I could peer onto the road below, where I spotted the occasional dirt bike, or up into the canopy, where a small bird came to rest and defecate on my arm.

I did not blame my companions’ desire to heal. Nor could I deny that all manner of spirituality saved people. I had begun writing about Native communities in my early twenties—the magazine I worked for had assigned me a story about the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation in North Dakota, and that story led to others. I’d been invited by Native people to sweat lodges and sun dances, and I had seen the way they helped people, and witnessing this healing had helped me too. I didn’t doubt the cathartic potential of rituals and plant medicine. I doubted that people could be healed by traditions created by communities they had little desire to understand.

As I watched the days rise and fall on the cliffs, I wondered about the people who had last occupied this canyon before settlers claimed it—the Eastern Shoshone, the Shoshone-Bannock, and Ute. I thought of my first private call with Linda. The idea of engaging in a ceremony taken from Native people, on land stolen from Native people, in order to pray to acquire land made me queasy. After that conversation, I’d called a roadman and sun dance leader I knew, T. J. Plenty Chief, from the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation. I’d attended a sun dance he hosted once a few years before and knew that every spring, in preparation for that ceremony, he put people “up on the hill,” the words he used for vision quest, or “hanbleceya.”

“What if you choose the wrong intention?” I asked.

“Ultimately, it’s up to the medicine,” he said. “The medicine makes you humble.”

Plenty Chief had been raised in the NAC and was authorized by one of his uncles to run peyote ceremonies. The men in his family had taught him how to fell and strip tepee poles; how to shape the clay half-moon that borders the central fireplace; how to be a role model for those depending on him. One uncle also warned him about white people soliciting access to the ritual. Over the NAC’s lifetime, peyote ceremonies had become an essential tool to resist and heal from the trauma of colonization, even as Native families and societies were torn apart. “There was a fear of losing what little we have left,” Plenty Chief said.

He knew about James Mooney and Oklevueha. “I would be very careful,” he said. He recommended I call Sandor Iron Rope, who since retiring from his role as NACNA chairman had helped to found the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative (IPCI). The IPCI intends to buy and lease land in Texas, where peyote naturally grows, to secure a supply for Native practitioners. The cactus was hard to come by, and this scarcity was one reason NAC leaders discouraged sharing it outside Indigenous circles, but there was also a metaphysical rationale: “It’s disrespectful to say the peyote is just a plant,” Iron Rope told me. “It has a culture tied to its biology. It has a history.” Some people have begun to grow peyote in greenhouses, but Iron Rope believes that this strips the plant of its culture and therefore its spiritual power. “Indigenous people are of the land, and when they tend to the land, they tend to that history. If you don’t have that history, it’s hard to understand. You say, ‘I respect the medicine,’ but sometimes respecting things is just leaving them alone.”

After that call, I decided I couldn’t partake in the peyote. I hadn’t told Gent, who’d given me a small baggie of it and suggested that I take a little each night of the vision quest—not enough to feel high, but to prime me for the ceremony in a few days. I thought of bringing it to Plenty Chief, but it was illegal for me to carry it. So, on my last night, I folded the medicine into a yard of red cloth and tied it around the maple tree.

At sunrise, I heard screams. I thought it was Miriam, then listened longer and knew it was Sofia. In our first days together, Sofia had shared that her mother committed suicide when she was ten years old. She had been stoic as she told the story and remained that way through Linda’s attempts to break her down. Now I listened as she wailed, crows cawing back at her. When she got to camp an hour later, the rest of us already sipping tea and broth, she looked weightless, radiant.

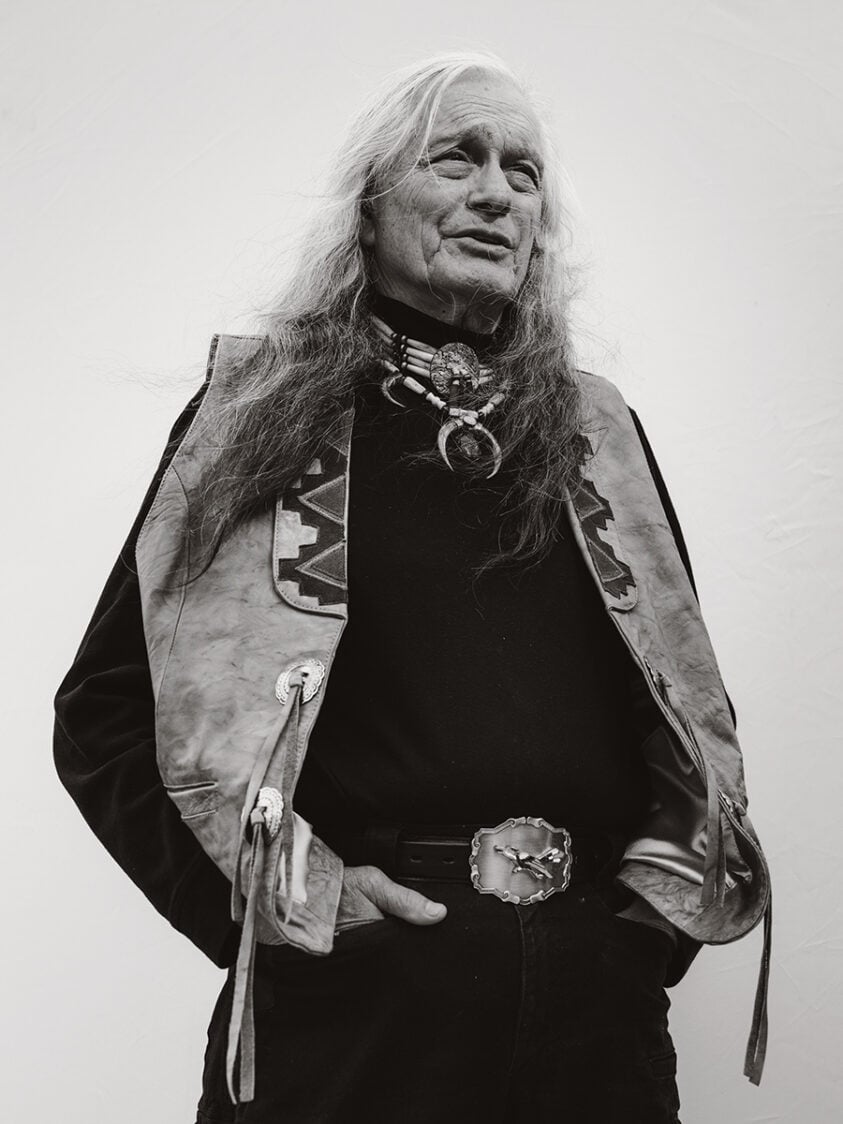

James Mooney in front of his house

After showering near the city of Logan that evening, I rode with Gent back to the canyon. I asked about the tension I had sensed between him and his mother and learned it had to do with James Mooney. Gent had been sixteen years old when Linda invited Mooney to live with them. “He stole my brother’s car and wrecked it, and it was like, ‘Why is this guy in our house?’ ” Gent said. “I think the story was that she liked him.” After Mooney left their home, he remained a force in their lives, and he led the first peyote ceremonies Gent attended. “It was like going to therapy on medicine,” Gent said. The peyote pulled him inward. The beliefs and lessons he’d encountered in those ceremonies made sense to him in a way his Mormonism never had. “They’re literally connected to the physical world that I can see,” he said. “Like the fact that we’re all related connects to what we know about science.”

In his twenties, in the Bay Area, he’d begun attending sweat lodges several nights a week through the Seven Circles Foundation, which hosts ceremonies for Native and non-Native people. These ceremonies were led by a Kickapoo/Sac and Fox man named Fred Wahpepah. There Gent began to feel a tension between traditional ways and the New Age interpretations of his mother and Mooney. Mooney’s approach didn’t match the traditions in the NAC, nor did it resemble any of the other Indigenous ceremonies that Gent was becoming familiar with. In the sweat lodges with Wahpepah, as well as later sun dances and peyote ceremonies with other Native people, he noticed that each had a distinct set of rituals, which the facilitator couldn’t invent but had to learn. “My mom runs ceremonies in the way she was taught by James,” he said. “She likes to play psychiatrist, but she’s not trained for that.” He said he’d seen people get worse after ceremonies—it cracked them open—and with Linda and Mooney’s practices, participants didn’t have a way to process all that came up. Rituals passed down from one’s ancestors required more humility, Gent thought. “I’d see people ask Fred and other Native elders, ‘What do I do?’ and they would be like, ‘Why are you asking me? I go pray.’ ” Mooney, meanwhile, had an answer for everything. Gent also said that it seemed Mooney preferred congregants who had money over those who did not.

It’s unclear how lucrative Oklevueha was or is for its operators. It is clear, however, that it owes much of its success to Mooney’s claim that membership legally protects the use of not only peyote but also other psychoactive substances. “It’s very misleading,” Gent told me. “People get arrested all the time.” Before Mooney’s first trial, state investigators had interviewed Oklevueha members and found them perplexed. “When asked if he was enrolled as a member of any Indian tribe, one person said that he was enrolled in ‘the tribe here today ran by James Mooney,’ ” a court document noted. “Another confessed, ‘I don’t know what that exactly means. I have a card that identifies me of Oklevueha Earthwalks Native American Church.’ ” In 2015, a self-described “bona fide medicine man” in Michigan was convicted of growing four hundred marijuana plants despite presenting an ONAC card to authorities. The next year, Mooney’s son, Michael, lost an attempt in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals to certify marijuana as an NAC sacrament.

In 2018, Gent had a falling out with Mooney. According to Gent, Mooney asked the SWCI to route its income through ONAC, and Gent refused. The Oklevueha governing council, led by Mooney’s wife, then demanded that Linda ban Gent from ONAC ceremonies, and when she wouldn’t, Mooney rescinded his support of the SWCI and shuttered another Oklevueha branch she’d founded. “That was the last straw,” Gent told me. “Like, my mom, after everything she’s done for you?”

A few years ago, Gent took a DNA test and confirmed his suspicion that, despite his mother’s claims, he had no Native American ancestry. (He still believes Mooney is of Native descent.) He had never put much stock in being Native, knowing all along that he wasn’t a part of an Indigenous culture, and the results didn’t change his feelings about peyote or his desire to share it. “Medicine grows on Mother Earth, and Mother Earth supports all people,” he said. When I asked how he’d respond to those who oppose his hosting peyote ceremonies, he said, “The truth: I wasn’t seeking to appropriate anything, but this is what I grew up with, and it’s what I love. So it’s what I do.”

James Mooney

I heard from Gent that Linda was trying to make amends with Mooney, so I asked her to introduce us. In July, I would return to Salt Lake City and stay at her ranch house in nearby Taylorsville, half the rooms surrendered to books about Indigenous spirituality. I slept in the basement, which had been converted into four bedrooms, two of which were occupied by recently homeless people, referred to her by a local shelter.

Mooney lived with his wife in a duplex in Spanish Fork, forty-five minutes south of Linda’s. Mooney’s stepdaughter, in her thirties, answered the door and led us through a kitchen decorated with woven baskets and blankets, then to a pergola in the backyard, where we sat in deck chairs around a fire pit. Mooney appeared from the kitchen after us, light on his feet, seeming younger than his seventy-eight years. His gray hair, which hung to mid-chest, was tossed over one shoulder, and he wore a button-down and cargo shorts. He shook my hand, looking me up and down. “I want to know about you,” he said with a gravity that conveyed real interest. Then he talked for more than an hour in long loops, a solar system of digressions, without asking a question.

“Can I ask some questions?” I finally interjected.

He fixed his eyes on me like he was considering how much to divulge. “You didn’t say anything about the CIA stuff?” His question was for Linda, who had fallen asleep.

“Nope,” she replied drowsily.

“What I’m going to share with you is going to blow your mind,” Mooney said.

In 1982, he told me, six years before he first used peyote, during a long layover in Los Angeles, he decided to tour the neighborhood where he’d grown up, and there he encountered an old classmate who mentioned events of which Mooney had no recollection. He realized then that all memories from his childhood had been mysteriously erased (never mind that he had just brought himself to his childhood home). The cause of this amnesia, he elaborated, was that he had been drafted as a child into a federal program to train assassins and had been assigned to kill people all over the world. After being injured in Vietnam, he’d undergone “deprogramming” to forget that any of it had ever happened—a tale remarkably similar to the backstory of the Bourne movie franchise.

After our meeting, Mooney would send me selections of his autobiographical writing, some of which was not meant to be factual, he said. I would try to interview him twice more. When I asked why he believed it was essential to share peyote with white people, he told me about the “peace” the drug brought him. “People need this medicine, regardless if they’re Indian, Caucasian, African, Asian,” he said, then began an unrelated monologue. In August, he would leave me a voicemail saying, “I am very interested in seeing you financially successful.” After that, I gave up.

When I asked Linda what she thought of Mooney’s stories, she said, “I just accept James for James. Gent will tell you he’s a liar. But James isn’t. He’s the visionary, so he’s going to create the vision.”

The peyote ceremony was held in the tepee behind Miriam’s house, a manicured stucco at the foot of the mountains. A man named Nathan Strong Elk, of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe and the first Indigenous person I’d seen since my arrival in Utah, would lead us in the ceremony, which Gent said would be traditional, unlike those led by Linda and Mooney. But Strong Elk, who was in his early sixties, and wore a black T-shirt and jeans, was a friend of Mooney’s and helmed his own Oklevueha branch (as far as I knew, the only member of a federally recognized tribe to do so). Were we to assume that Strong Elk planned to share the NAC traditions with us? Gent had told me that Strong Elk would be splitting the ceremony’s profits with Linda. (Strong Elk later denied this but said he accepts gifts.)

At dusk, we lined up outside the tepee and filed in. Arcing around the fireplace at the far end was a half-moon of sand, and, at the top of this crescent, some bone whistles, eagle wing fans, and a sacred pipe had been arranged into an altar. Strong Elk stood on his knees at the altar, Gent beside him. They opened the ceremony with a tobacco offering and songs, then showed us how to roll tobacco into corn-husk smokes, waft the vapor over ourselves, and prop the smokes against the half-moon. When the peyote tea was passed around, I took a small cupful and placed it beside me without drinking. I watched as others scooped ground peyote, a fine beige powder, into their palms, then washed it down with the tea. As people began to moan and wretch, Strong Elk tossed cedar onto the fire, fanning the smoke over their bodies.

Between songs, he passed a wooden staff around the tepee, offering each person a chance to speak. I would lose track of how many times the staff circled. The people around me appeared to at once retreat into themselves and hurtle forward as they divulged secrets. A woman shared the story of her boyfriend’s betrayal; another, a sexual assault. When the staff reached Miriam, she circled the tepee clockwise with her gaze, staring into each of our eyes for half a minute. The effect was ecstatic, the energy turned feverish, and when it was Sofia’s turn, she began wailing and convulsing in what I realized was a reenactment of her daughter’s birth. Soon everyone in the tepee was screaming.

Was this healing? At the end of the ceremony, as Strong Elk packed his instruments into a wooden chest, a woman beside me leaned over and reached for a bone whistle resting on the altar. Strong Elk raised a hand to block her. “I’m asking for your whistle,” she said. Women were not supposed to touch bone whistles, he explained. “Who said that?” she asked, and reached again for the whistle. Strong Elk rummaged in his chest and found a bamboo whistle to offer her, but she refused it, pointing: “I want that one.” I felt an intense desire to yank her back, to say she had no reason to believe she deserved what she coveted. Then, from across the tepee, Linda, who had been quiet most of the night, spoke firmly: “Stop.” The woman fell from her knees onto her back. “I don’t know what I’m supposed to do,” she sobbed. Linda crawled to her and took her in her arms, rocking her like a child.

I had left open the possibility of witnessing revelations that night. I still did not doubt that white people could learn things from Indigenous ways. But the participants at the peyote ceremony were not devoted to any Native spiritual tradition. Deafened by their own pain, they seemed to be devoted instead to the idea that they could have everything they wanted.