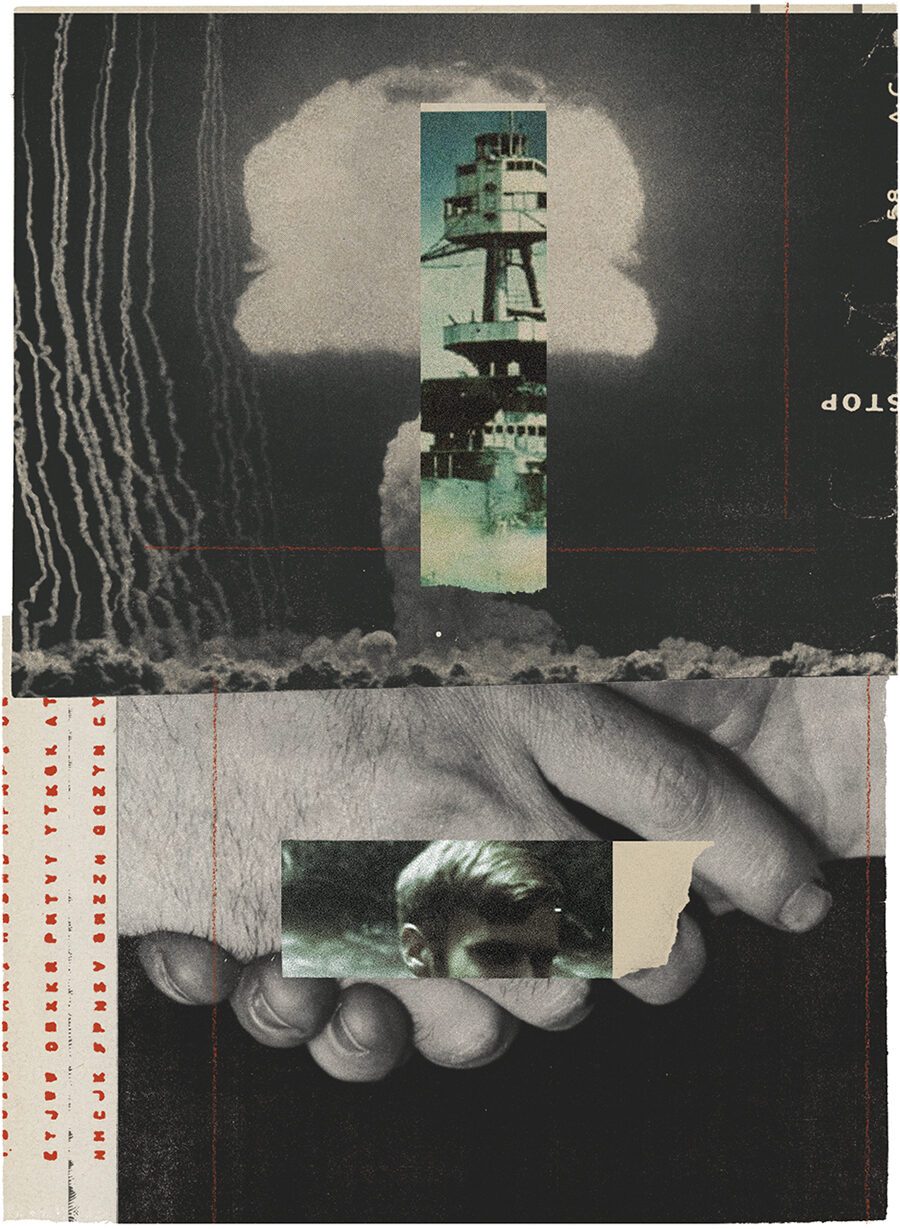

Collage by Mike McQuade. Photograph of Jackson Lears courtesy the author. Other source images © Galerie Bilderwelt/ Getty Images; MPI/Stringer/Getty Images; FPG/Getty Images

The war in Ukraine has resurrected the ultimate technocratic fantasy: a winnable nuclear war. Intellectuals at the Hoover Institution are urging American strategists to “think nuclearly again,” reestablishing the idea that nuclear weapons are tools to assert U.S. primacy over Russia and China. This isn’t just talk. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists recently noted “steadily increasing U.S. bomber operations in Europe”—some near the Russian border. Though most Americans are unaware of it, escalation toward nuclear conflict is already under way.

In this strange atmosphere, I feel moved to revisit my own experience as a naval officer on a nuclear-armed ship more than fifty years ago. My story is all too relevant today. As Daniel Ellsberg demonstrates in The Doomsday Machine, the shape of U.S. nuclear strategy has remained unchanged since the early Sixties.

Those were the worst years of the Cold War, when John F. Kennedy’s confrontational foreign policy provoked face-offs with the Soviet Union in Berlin and Cuba. I was in junior high, and had already been exposed to an iconic journalistic form of the nuclear age: a map rendering the reader’s own metropolitan area as a target, with concentric circles of damage and death radiating outward. The widespread assumption was that nuclear weapons were weapons unlike any other, and that using them would mean crossing a Rubicon to Armageddon. The use of nuclear weapons, no matter how precisely targeted, would put adversaries on an escalator moving upward, with retaliation growing in force each time. Given the size of both sides’ nuclear arsenals by the early Sixties, the consequences were unimaginable.

Still, Americans tried to imagine them. The number of dead within hours, experts predicted, would exponentially dwarf the estimated fifty-to-sixty million civilians killed in World War II. Over the longer term, the statistical projections quickly rose to mind-numbing absurdity. The mind reeled. Popular culture was marked by depictions of cities reduced to smoldering ruins, the few humans who remained dying slowly from radiation sickness and grievous injuries, scratching out an existence in a world where the water, air, and soil had been rendered poisonous for centuries, and where descendants would suffer birth defects for generations. On a post-apocalyptic planet, the survivors would envy the dead. This would truly be a war without winners.

How had we come to this dark place, on the brink of disaster because of a quarrel over rival economic systems? From the earliest days of the atomic age, prescient critics such as Lewis Mumford saw madness in pressing forward with new weapons development; they were still around in the Sixties. Yet the arms race continued, and politicians from liberal Cold Warriors like Kennedy to pseudo-libertarians like Barry Goldwater continued to treat nuclear weapons as an instrument of policy. A rising generation of brash nuclear strategists argued—by way of rules-based, algorithmic rationality—that a nuclear war could actually be won. Throughout my formative years, the threat of apocalypse was palpable and pervasive. But I had no idea that I would soon have an intimate look at nuclear war-making.

When I was in college, the nuclear arms race seemed abstract in comparison to the immediate challenge posed by the Vietnam War. As I learned about its colonial roots, I came to oppose it; but like many young men of my age, I had no idea that there was an alternative to serving in the military. Rumor had it that college deferments might soon be abolished, and many advised joining the Reserve Officers Training Corps, which would at least guarantee that I could finish my degree. So I joined the Naval ROTC.

My professional specialty was an open question. An English major making the best of a bad lot, I settled on “communications,” naïvely hoping that I might get lucky and end up writing bland press releases for a shore-based command. Weeks after our college graduation, my wife Karen and I headed to San Diego, where I boarded the USS Chicago (CG-11), a World War II cruiser that had been updated to carry tactical nuclear missiles. As a Signals Officer with a top-secret clearance, I was assigned a range of duties that included decoding the message that would order the ship to launch those weapons. I was to be a link in the chain that led to nuclear war. This was not what I had imagined when I signed up for ROTC.

When the Chicago was not in the Gulf of Tonkin, tracking Russian-made North Vietnamese fighter jets, it was off the coast of California, jousting with Soviet spy ships masquerading as fishing trawlers. Our captain was itching for action, partly in hopes of a promotion.* Careerism encouraged ambitious officers to believe that nuclear weapons could be deployed like any others, and the authority to launch them was delegated widely and deeply. But the captain was more than a careerist. He was a tall, ramrod-straight son of a bitch—cool, contemptuous, and animated by a delight in his own power and a controlled rage at his subordinates, which was everyone aboard the ship. When I attempted a few pleasantries upon first meeting him, in the officers’ club at the Subic Bay naval base in the Philippines, he snapped: “Don’t snivel at me!” At his change-of-command ceremony, he lamented that “our weapons have not been bloodied in battle.” His successor was a more decent man, but given to drink and unpredictable rages. It is chilling to imagine either with a finger on the nuclear trigger.

Serving on a nuclear-armed ship was a profoundly different experience from playing at close-order drills on a university ball field. I was constantly reminded of the way that contemporary war-making enveloped civilian populations. What happened to the civilians greatly concerned me. But so did what happened in the minds of the men who attacked them—including, potentially, myself. These were my thoughts after overhearing two of my shipmates discuss the smell of burning human flesh with bemused equanimity. But what mostly troubled my conscience was my shipboard assignment, which may well have required me to initiate a chain of events leading to the deaths of countless civilians.

As I tossed in my bunk, I read everything I could get my hands on that might clarify my relationship to the modern way of war. A few books helped me combat my sense of helplessness within the impersonal U.S. war machine. William Barrett’s probing philosophical study Irrational Man made the compelling argument that the prospect of nuclear annihilation had forced us all to encounter nothingness and incorporate the shadow of death into our everyday consciousness, as the existentialist tradition urged. The most emotionally helpful book—though I can’t remember a word of it—was an anthology on how to end the nuclear arms race, with the reassuring title Peace Is Possible. Those three words became a sort of private mantra.

But the book that spoke to me most directly was Theodore Roszak’s The Making of a Counter Culture, given to me by Alton Wesley Powell, an enlisted man who worked as a clerk at the training center in San Diego and became a close friend. He was an extraordinary and tragic character, blond and cherubic, a closeted gay man. He had been a boy preacher in McMinnville, Tennessee, and had taught at a prep school after getting a theater degree at Cornell. Six months or so after we met, he was discharged from the Navy for mysterious reasons and committed suicide. He was in our lives all too briefly. A.W., as we called him, was a poet and a scholar who combined his rare capacity for reflection on ultimate questions with a keen sense of irony and a puckish sense of humor. He was a shining example of the richness and complexity of the antiwar counterculture in San Diego. Together we often discussed Roszak’s big idea, which was the deadening impact of technocracy on our mental lives, especially on the ways we think about war. As Mumford and other critics had foreseen, technocratic rationality could rationalize conduct that was essentially mad.

Roszak’s theme resonated powerfully with my own experience—the Navy showed me technocratic rationality in action every single day. I saw at close range how statistics and jargon could numb our awareness that we were firing at human targets. I spent eight months trying not to think about the obvious implications of my job—until a bureaucratic requirement forced me to make a choice. The Pentagon implemented a Sealed Authenticator System that required two officers to decode the order to launch. I was selected to serve on this team, but membership required an interview with the chaplain—to see, as my department head said without irony, “if you have any particular axe to grind for or against nuclear war.” The statement, absurd as it was, concentrated my mind. The Navy was looking for the ultimate neutral technocrat. I would have to refuse.

Leaving for Canada did occur to Karen and me, until a friend came up with a better plan. Ken Donow was a graduate student in sociology at UC San Diego, whom we knew through A.W. Ken was a Jewish New Yorker who was understandably tired of my complaining. “The Navy doesn’t want guys with your views in its officer corps,” he told me. “If you want to get out, you can get out.” He handed me a card that read west coast counseling service. This was, in effect, my official entrée into the antiwar counterculture.

San Diego was a big military town, but it was also full of antiwar dissenters—many had declared themselves conscientious objectors after beginning active service and still managed to receive honorable discharges. One of my counselors, a slight, bearded young man nicknamed Rabbit, was one such case, who now advised people like me. He was good at playing tennis as well as interpreting military regulations; on the desk in his tiny office, he kept an empty tennis ball can that he’d affixed with the label everything here is free, brother. From him I learned that you could qualify as a CO if you had been on active duty for at least six months and could show that your views had altered since the beginning of your service. That worked for me. My shipboard assignment had enlarged and sharpened my antiwar stance, from opposing the Vietnam War to opposing all war—or all war that required killing non-combatants, which in the modern world is the same thing.

The local command recommended that I be given an unsuitability discharge (the category handed out for bed-wetting and alcoholism, as well as homosexuality and “other aberrant sexual tendencies”), rather than a CO discharge because, though I was sincere, I had “no affiliation with a recognized religious organization or sect that embraces either non-violence or pacifism.” In fact, the Navy’s regulations did not require such affiliation; it demanded only belief in a “Supreme Being.” My reverence for “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower” was my version of that belief. Furthermore, criteria for conscientious objection were being widened even while my application was under consideration, as the Supreme Court ruled that an avowed atheist could claim draft exemption as a CO. When I brought this to the attention of my executive officer, he exploded: “The Supreme Court has nothing to do with us!”

In the end, I was lucky. The Pentagon rejected my local command’s interpretation and granted my status.

I was no doubt the beneficiary of class privilege; an enlisted man I remember only as Jacobs, who had also made a CO claim, was not. He was taunted mercilessly by the chiefs and other senior enlisted personnel; his application went nowhere and was delayed endlessly. Eventually, he gave up and attempted to flee to Canada, where he was picked up at the border as a deserter by the FBI. By contrast, I could depend on my officer status to protect me from overt hostility. I had been to college and could ask my former professors to write letters of support.

The most memorable of my supporters was my fellow officer Reggie Young, a black law student from Ann Arbor who was smart, thoughtful, and funny as hell. He brilliantly impersonated the executive officer, a thin-lipped, humorless South Carolinian with ill-fitting dentures. Once Reggie and his wife Sue learned that I had applied for CO status, they offered me and Karen their entire life savings to cover legal expenses. We declined but have always remembered their astonishing generosity.

Among many other things, my experience in San Diego taught me how official secrecy undermines truth-telling—which in turn undermines democracy. During my CO application process, the executive officer’s assistant informed me that my reference to the Chicago’s nuclear weapons had to be removed because the Navy’s policy was to deny that those missiles were nuclear-armed. “Why, probably three-quarters of the people of San Diego don’t know we carry nukes,” he said. I realized then that the most dangerous purveyors of disinformation were not conspiracy theorists but the military, the intelligence agencies, and their stenographers in the mainstream press.

Still, the public discourse of the Seventies seems crystalline compared to the murk produced by our contemporary media. In the late Sixties, distrust of government-produced disinformation was already on the rise, fueled by truth-tellers like Ellsberg, I. F. Stone, and Seymour Hersh, who exposed the systematic mendacity of the military and the intelligence agencies.

But after the humiliating withdrawal from Saigon in 1975, political fashions changed. Policymakers fretted that a “Vietnam Syndrome” would discourage military interventions overseas; major newspapers, led by the New York Times, announced that the public’s right to know had to be balanced against the government’s need to keep secrets. Meanwhile, the architects of war continued a trend that had begun under Kennedy, moving away from deterrence and toward a more flexible development of tactical nuclear weapons. What energized this shift was the technocratic dream of precise control over war—the least predictable of human enterprises.

This vision began to take shape when the Carter and Reagan Administrations deployed Pershing and Cruise missiles in Europe. Reagan promised a return to the confrontational posture of the early Kennedy years when he denounced the Soviet “evil empire” and inaugurated a huge buildup in Pentagon spending.

Yet there was pushback. The deployment of the missiles provoked mass protest and led to a movement for European nuclear disarmament, which had the backing of the British Labour Party. Stirrings of unprecedented public diplomacy between American and Soviet citizens, combined with European antiwar activism, sustained a broad and powerful transatlantic peace movement that focused, at least in the United States, on demands for a freeze in the development of new nuclear weapons.

The Nuclear Freeze movement was a popular uprising that garnered support across the country. It helped create a mass audience for the 1983 TV movie The Day After, which powerfully evoked the impact of a nuclear strike on a Kansas town from instant incineration to the slow, painful death by radiation sickness, reminding some hundred million viewers what was actually at stake. Addressing a panel of experts assembled by ABC to discuss the film, Henry Kissinger sneered and sputtered. But Reagan watched it in a private screening and was “greatly depressed,” as he wrote in his diary: “My own reaction was one of our having to do all we can to have a deterrent & to see there is never a nuclear war.”

On January 16, 1984, he delivered a speech insisting that the United States and the Soviet Union had “common interests, and the foremost among them is to avoid war and reduce the level of arms.” He further declared his support for “a zero option for all nuclear arms.” It is an arresting experience to read these words, coming from a man who had so recently committed himself to a moral crusade against an evil Soviet empire. It is also arresting because it is nearly impossible to imagine these words coming from the White House today. Reagan’s speech was written in the classic language of diplomacy—the recognition of interests shared by rivals, who may disapprove of each other’s actions but who need to agree to protect the general good. The speech’s author, Jack F. Matlock Jr., later became Reagan’s ambassador to the Soviet Union, and is now one of the few voices calling for diplomats to end the war in Ukraine. Matlock insists that, whatever domestic political aims the speech may have served, it was meant to be taken seriously by Soviet leaders.

Among them was Mikhail Gorbachev. Eventually he and Reagan agreed in principle on the aim of abolishing all nuclear weapons. But they never realized that goal, largely because Reagan remained committed to quixotic plans for a Strategic Defense Initiative. Though the talks between Reagan and Gorbachev produced major bilateral treaties and reductions in nuclear arsenals, abolition remained a dream. Still, the rosy afterglow lasted for years. Except for the occasional invocation of the “dirty bomb” that might be manufactured by terrorists, nuclear weapons largely disappeared from political discourse.

The war in Ukraine has brought them back into the public square. But to the extent that these weapons are discussed at any length, it is in the bland language of policy expertise. The moral and human meanings of nuclear warfare have disappeared behind a veil of indifference, while the U.S. insistence on total Ukrainian victory—even contemplating a recapture of Crimea—makes a nuclear exchange ever more likely. So does the increasing number of U.S. bombers on crisis alert in Eastern Europe, and the technocratic rationality that masks the madness of the nuclear strategists at the Hoover Institution and other think tanks.

The gravity of our situation is revealed in the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review, which was most recently updated in October 2022. The latest statement affirms U.S. opposition to a “No First Use” policy; it also asserts the validity of using nuclear weapons “in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its Allies and partners.” By implicitly leaving open the possibility of first use, the policy allows the United States to cross the nuclear threshold for something as vague as an ally’s “vital interests.” One could hardly ask for more permissive criteria.

Russia’s own statement emphasizes the retaliatory uses of nuclear weapons rather than explicitly invoking first use, but both sides allow for possibilities that might justify a preemptive launch. Both are poised to accelerate a nuclear arms race, unconstrained by any meaningful arms control agreements. And neither acknowledges the possibility of an accidental launch, despite past brushes with catastrophe.

These statements confirm a chilling conclusion: nuclear war is being normalized as part of a broader U.S. foreign policy of perpetual confrontation with actual or imagined rivals. Even during the darkest days of the Cold War, both sides recognized the immense threat posed by nuclear war, and the common interest they shared in avoiding it. But diplomacy has disappeared from U.S. foreign policy, which remains mired in moral rigidity. Earlier this year, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved its Doomsday Clock to ninety seconds from midnight, the closest it has ever been. What is to be done?

Ellsberg urges the dismantling of the Doomsday Machine—the huge arsenal of missiles possessed by both Russia and the United States—that can kill, maim, and sicken hundreds of millions on impact, but also blot out the sun for ten years or more, causing a worldwide famine that would put casualties into the billions. This is the ultimate climate change, and concern about it ought to bridge the unnecessary gap between environmental and antiwar movements. Avoiding doomsday would not require decommissioning all nuclear weapons—we might preserve enough to deter any potential attack, pending the ultimate goal of abolition. But amid the current war fever, it is impossible to imagine the United States beginning to dismantle any weapons, and that is a tragedy. For the dance of death to stop, one of the partners must step aside.