Federal police officers on the outskirts of Tijuana, Baja California, 2009 © Guillermo Arias

Discussed in this essay:

Drug Cartels Do Not Exist: Narcotrafficking in U.S. and Mexican Culture, by Oswaldo Zavala, translated by William Savinar. Vanderbilt University Press. 206 pages. $34.95.

The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade, by Benjamin T. Smith. W. W. Norton. 480 pages. $20.

In 2008, a plane crashed in the heart of Mexico City, near the National Museum of Anthropology. Juan Camilo Mouriño, the interior minister, and José Luis Santiago Vasconcelos, a former prosecutor known for fighting drug cartels, were both killed. The government said it was an accident. But many people believed—simply because it seemed like it might be true—that the cartels shot the aircraft down. Or that it was a government plot to rein in investigators looking into drug trafficking operations that might lead back to high places. Los Tigres del Norte, one of Mexico’s most popular bands, sang about the crash in an extended political allegory called “La Granja”:

A hawk has fallen

The chicks are asking

Did it fall by itself?

Or did the winds bring it down?

When I moved to Mexico City a year later, the crash was still the subject of elaborate conspiracy theories. A popular topic of conversation was whether the president of the country really wanted to wipe out the gangs or if he was perhaps in cahoots with one of them and using money from taxpayers and the United States to selectively target its rivals. The week before the crash, Mexican news outlets reported that the government had arrested high-level officials accused of serving as paid informants for cartels, as well as a mole in the United States Embassy who had been leaking information about Drug Enforcement Agency operations. That same year, the United States and Mexico established the Merida Initiative, a partnership through which the United States has administered some $3.3 billion in government aid to a Mexican regime known to have been infiltrated by the cartels.

In 2010, Los Tigres del Norte performed at the bicentennial celebration of Mexican independence on a massive stage erected on Paseo de la Reforma—the same avenue where the plane had crashed two years earlier. I arrived after midnight, and the five band members, dressed in suits and black cowboy hats, were well into their set, taking suggestions written on slips of paper and passed up to the stage. The crowd was dancing to “Contraband and Betrayal,” the song that made the group famous in the Seventies. It tells the story of a fictional drug runner, Camelia la Texana, who smuggles marijuana to California with her lover, Emilio Varela. When Varela tells her he plans to leave her, she shoots him and makes off with the money. The song helped make narcocorridos—songs glorifying traffickers—wildly popular. The classic version of “Contraband and Betrayal” ends with a shoot-out. But performing four years into a bloody escalation of the Mexican drug war, the band tapered off with accordion figures instead.

Later, they started playing “La Granja,” a turn away from their old material. Now one of Mexico’s biggest bands was criticizing the narcotraffickers and the corrupt officials colluding with them. “Their big hits are the old ones with the guns,” a man named Julio told me. “Listen to ‘La Granja.’ It is all about going against the narcos.”

“Is it about drugs?” his wife, Daniela, asked. “I don’t listen to the words. For me it is just music good for dancing.”

The drug wars nearly kept me from becoming a journalist. Partly it was fear. Last year, for instance, Mexico was the deadliest country in the world for reporters outside war zones, though it is much more dangerous for local than foreign journalists. The main problem, however, was that I didn’t understand the biggest story in the place I lived. And I didn’t see how the usual steps—calling people, driving around, talking, watching—were ever going to help me understand or write with anything approaching clarity. In the local newspapers, I read about cartel this and cartel that, supposedly in a struggle against one another for control. The papers made them sound like soccer matches: Tijuana vs. Guadalajara; Juárez vs. Sinaloa. Everyone knew about the faces sewn onto soccer balls, the warnings left in blood or carved into bodies. Parts of northern Mexico were changing from scenic destinations to no-go zones for outsiders. The violence hadn’t descended on Mexico City, and it was rumored that members of the government had made a deal with drug traffickers to keep it that way: a safe capital where businesses could operate. People speculated about what the traffickers got in exchange. But it crept closer and closer: in August 2010, bodies were strung up over a bridge in Cuernavaca, a flower-filled town south of Mexico City where the emperor Maximilian had his pleasure palace in the nineteenth century.

In 2012, William Finnegan wrote one of the few pieces of foreign journalism that reflected the confusion I felt at the time. “When Mexicans discuss the news,” he said, “they often talk about pantallas—screens, illusions, behind which are more screens, all created to obscure the facts.” I never sorted out fact from rumor well enough to even try to write about the drug wars. I left, then returned five years ago, then left again. The rumors and speculation have only become more baroque. So naturally I was interested to read a recent book that offered a new way of thinking about the open question of the drug wars: about who—or what—might be behind the screen. Drug Cartels Do Not Exist, by Oswaldo Zavala, a Mexican journalist turned professor, asks us to consider what at first may seem an absurd proposition: What if there are no cartels? What if it’s all a lie, a cover-up? Behind the screen, Zavala proposes, is not a narco killer with gelled hair and a taste for expensive tequila—but the police, the army, and various arms of the state.

In 2007, Felipe Calderón was a new president with a weak mandate and a weak chin. In a political stunt, he would go on to climb into baggy combat fatigues and declare the war on drugs his number one priority. Two years later, Calderón ordered the armed forces into the fight and unleashed death on a scale not seen since the Mexican Revolution. By the government’s own count, 105,000 people have been killed or forcibly disappeared since 2006. Groups of mothers roam the countryside, searching for the bodies of their children.

The standard explanation given by members of the Mexican government, the U.S. government, and news articles based on what journalists like to call official sources, is that this is “drug war violence”—a phrase that sounds like it should mean something but doesn’t. Who is killing whom? Here is the usual capsule history: Once upon a time, there was peace in the drug trade. Certain kingpins were in charge, and everyone knew whose territory was whose. This story is familiar from official sources in Colombia too. The Eighties and early Nineties were the top-dog years for the Medellín Cartel, led by Pablo Escobar. Then, after the U.S. and Colombian governments ratcheted up pressure, they squeezed the trade over to Mexico, and eventually to the Sinaloa Cartel, led by Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. The cartels were named, often by the DEA, after the areas they supposedly controlled. The story goes that when the kingpins were captured, there was a battle for turf and supply routes. In other words, traffickers killing traffickers. Nothing to see here.

Zavala’s book, translated from the Spanish by William Savinar, offers a different explanation. Zavala is one of a growing number of observers who see the cartels and kingpins as a distraction from the real story: who is using the drug war to consolidate power and make money. At its most polemical, his argument is that the cartels don’t exist at all, that they are a convenient bogeyman for the U.S. and Mexican governments. The title of his book is taken from two interviews. One, from 1994, is a Time magazine conversation with a trafficker who allegedly led the Cali Cartel in Colombia, despite denying its very existence: “There are many groups, not just one cartel. The police and the DEA know. But they prefer to invent a monolithic enemy.” The second is from an interview by the journalist Ioan Grillo with an attorney who defends drug traffickers in Colombia:

Cartels do not exist. What you have is a collection of drug traffickers. Sometimes, they work together, and sometimes they don’t. American prosecutors just call them cartels to make it easier to make their cases. It is all part of the game.

One defense, of course, is to claim that a criminal structure is merely a figment of a prosecutor’s overactive imagination. Still, from the perspective of the Colombian, Mexican, and U.S. governments, it makes more sense to say you are going after the leader of a group rather than plucking important people out of a swirling mess while leaving the mess more or less intact. President Richard Nixon announced the war on drugs in 1971, and drugs have been winning the war ever since.

Zavala last worked as a journalist several decades ago, and he trained with a group of reporters and photographers in Ciudad Juárez, whom he thanks fulsomely. Still, the book is not journalistic, nor is it historical. It is an odd but appealing mix of argument and analysis. His main concern is not to establish the truth of the matter, but rather to show the reader why it is nearly impossible to do so. This, in short, is because most of the available information comes from “official sources”—the government and the police. Zavala emphasizes how an official story gains authority as it shifts over into the cultural sphere. The representations of the war on drugs move out in concentric circles from an uncertain reality, based on poor or false sources. In his view, newspaper reporters uncritically repeat the government narrative, novelists embellish it, then Netflix seizes on the obvious gold mine. It is both a convenient cover story and good business. This is how we end up with a certain idea of the drug war—an image of a gunslinger in cowboy boots standing over a dead body. The dead body is real, says Zavala. But the boots are on the feet of a policeman, or maybe even a politician.

Unlike much academic writing in English, Zavala does not quote others only in order to agree with them. He cites with his knives out. He accuses the television series Narcos of helping to promote the government line. More surprisingly, he makes the same accusation against work by prominent journalists and authors, such as Anabel Hernández, Diego Enrique Osorno, and Yuri Herrera. Zavala maintains that there is little accurate reporting on the drug wars, a stance that has understandably been unwelcome in Mexico—not least among journalists. Nevertheless, the underlying premise seems sensible enough: we should listen to the friends and families of victims when they tell us who has been killing them. And what they say is that it isn’t narcos killing narcos. It is the government—the police and the military—killing young men and disappearing young women. Military officials routinely kill women after acts of sexual violence. They torture young men to obtain confessions, and forcibly disappear them. Indigenous people who resist mining on their lands or protest theft of their water are killed, supposedly by narcos, but often at the behest of corrupt local politicians. This is what Cristina Rivera Garza, in her book Grieving, calls “the misnamed war on drugs,” which is actually “the war against the Mexican people.”

Top left: Lidia Alvarez waiting to receive the bodies of her brothers, who had been missing for three years, in Los Mochis, Sinaloa, 2020 © Yael Martinez/Magnum. Top right: Weapons seized from narcotraffickers in Sinaloa, 2008 © Jerome Sessini/Magnum. Bottom right: A child in Cochoapa el Grande, in the poppy-producing region of Guerrero, 2021 © Yael Martinez/Magnum. Bottom left: Mass graves in Tijuana, Baja California, 2018 © Gary Coronado/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

A lot of the language used to talk about traffickers and cartels is confusing, perhaps even intentionally misleading. Take “turf wars”—struggles over what in Spanish is called la plaza, the main square. Turf wars go back to the earliest days of Mexican drug trafficking. But it wasn’t traffickers duking it out: it was policemen and politicians. They wanted their piece of a protection racket.

The government war on drugs in Mexico wasn’t an import from the United States, at least not in the beginning. A century ago, an authoritarian Mexican government decided to crack down on a drug that had come to be associated with poor and indigenous users. Introduced in the sixteenth century by the Spanish, who wished to grow hemp for rope, cannabis gradually gained a Mexican name, marijuana, and became a home remedy. It became the drug of choice during the Mexican Revolution. In his myth-busting and perversely enjoyable history The Dope, Benjamin T. Smith relays one theory about where the word originated: “Juan was the name given to the average Mexican soldier. His camp wife was often termed María, María-Juan became Marijuana.” Mexico banned growing and selling the herb in 1920, before the United States did. Mexico also banned the importation of opium, which prompted enterprising farmers to start planting poppies in the Golden Triangle, an area of northern Mexico that now produces a healthy portion of the United States’ cocaine.

Once the United States banned marijuana in 1937, running it across the border became good business. Mexican families smuggled alcohol, then marijuana, then cocaine. According to Smith, the Mexican government began cashing in on the trade, too. The first protection rackets emerged in northern Mexico, creating a model that persists today: policemen and politicians take regular payments to look the other way when certain people move drugs, then crack down on their rivals. Everyone is happy: there are arrests to publicize, and those in on the arrangement make plenty of money.

Smith writes that some of the early protection rackets helped fund schools and infrastructure, especially in Ciudad Juárez and Baja California. Later, local politicians tended to line their own pockets. But the traffickers wouldn’t pay up without persuasion. If that proved violent, all the better: protection rackets could be made to look like crackdowns. That’s where the “drug war” violence began. Drugs had to be made illegal; traffickers needed to learn to accept being shaken down. Smith writes of an early governor of Baja California, Esteban Cantú, who decided that imposing the change involved “an unpleasant errand. To prove his antinarcotics credentials and persuade traffickers to pay up, Cantú killed a group of established traffickers.”

By the Seventies, traffickers were making money hand over fist, and the local protection rackets went national. Drug lords had state police badges. One Mexican president, José Lopez Portillo, had his childhood friend who’d beaten back his schoolyard bullies hired as the head of the Mexico City police. That friend, Arturo Durazo Moreno, also happened to be the head of a major protection racket helping run cocaine up to the United States. Durazo hired his cronies, who had no interest in stopping trafficking but came down hard on their rivals. Unlike Zavala, Smith is more focused on the history of the trade itself than on narcoculture. But he does note that the Federal Judicial Police—later shut down because of corruption and criminal activity—adopted a style of dress that one DEA agent called “Mexican federale couture”: “tailored leisure suits, ostrich-skin cowboy boots, and gold bracelets with their names engraved in diamonds.”

The book is built on archival research, interviews with former DEA officials, and valiant attempts at triangulating sources to estimate the size of the industry over time—though Smith does cite Peter Andreas and Kelly Greenhill’s observation that “drug statistics are basically like lines of cocaine. The more you know about how they were produced, the less attractive they seem.” Smith credits Mexican and foreign journalists who have told parts of this story before, but he has new evidence on the state protection rackets. He is convincing on this point: the extreme escalation of violence is “not so much in the DNA of trading in narcotics as in the DNA of prohibiting the trade.”

Though the book centers on Mexico, Smith is at pains to show that police in the United States were also in thrall to powerful politicians and, like their counterparts in Mexico, used the war on drugs as a convenient excuse for racist and classist repression. The United States, he notes, had prohibited marijuana by “repeating the old Mexican prejudices, which linked the drug to insanity and violence.” Tabloid headlines about indigent killers crazed by dope were a staple on both sides of the border before prohibition. Marijuana was associated with hippies and those who opposed the Vietnam War. After Nixon declared the war on drugs, the prison population shot up from 200,000 to 2.2 million. Half the people currently in prison are there for drugs. Most are people of color.

During the same period, Mexico was busy using drugs as an excuse to repress its own counterculture. In 1968, soldiers in plain clothes infamously ambushed a student protest, killing at least three hundred people. Less well-known was the dirty war—forced disappearances, murders of students and suspected communists—centered in Guerrero, where the cultivation of poppies and marijuana bloomed in the Sixties and Seventies. In Latin America’s first “death flights,” the bodies of leftist activists and guerrillas were flown out from military bases in Acapulco and secretly dumped in the Pacific Ocean.

It was around this time that the DEA started talking about cartels. The agency claimed that one trafficker said, “Let’s put it all in one place, deal with one person and set a price,” and that “it was like the OPEC cartel.” Smith writes that this change likely had “more to do with the DEA’s desire to create an obvious public enemy than with any wholesale restructuring of the drug business.” On the face of it, the word “cartel” doesn’t make any sense for the drug business in Mexico, then or now. Even if, pace Zavala, you believe that drug traffickers do control extensive territory and supply chains, they shouldn’t be called cartels. If there were a true cartel, operations would be centralized, and there would be less violence. In Los Zetas Inc., the political scientist Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera explains why she doesn’t use the term. “The formation of a cartel requires an agreement between competing firms or corporations with the aim of controlling prices and production or excluding the entrance of new competitors in a specific industry,” she writes. “Because cartel formation requires cooperation between different firms, the term ‘cartel’ should not be used to refer to drug-trafficking organizations in contemporary Mexico.” In other words, there are no cartels.

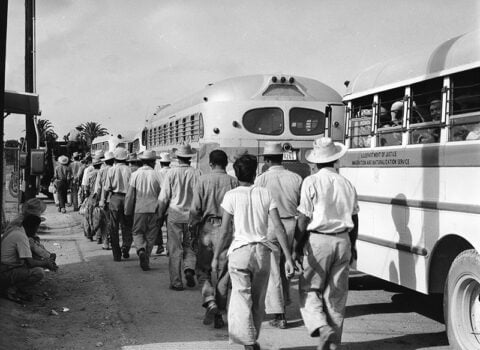

But there are plenty of deaths. In Mexico, the extreme violence of the drug war began in 1975, with the world’s first large-scale herbicide campaign targeting marijuana plants and opium poppies in the Golden Triangle and elsewhere, accompanied by military occupations and widespread torture. DEA agents referred to the campaign as “the atrocities.” The United States provided most of the chemicals and all of the aircraft. It was an utter failure. Trafficking marijuana transitioned smoothly into trafficking cocaine. The protection rackets continued.

Mexico was not fully a democracy until 2000, in the sense that opposition parties could not win national elections. Since the Mexican Revolution, a single political party—the Institutional Revolutionary Party—ruled the country. The peaceful transition of power in 2000 marked a democratic turn, but it also unsettled who would benefit from shaking down traffickers. The biggest change began under Calderón, who was president from 2006 to 2012. He called the military out to the streets, deploying soldiers to support, then supplant, the police. They have yet to return to their barracks. Zavala cites the sociologist Fernando Escalante Gonzalbo’s “simple analysis based on official figures” showing that the country’s violence sharply escalated after the militarization ordered by Calderón.

That violence has extended to the press: it is becoming increasingly obvious that it is not always narcos who are behind the murders of Mexican journalists. John Gibler is a North American reporter who has lived in Mexico for many years and is involved in a collective of journalists investigating the murder of the Chihuahuan journalist Miroslava Breach. “There’s this myth that reporting on the cartels gets you killed,” he recently told The New Yorker.

And yes, it can, if you publish specific information about who is doing what and where. But, if you look at the majority of the more than one hundred journalists killed in the last decade in Mexico, most of them were working on stories about the collaboration between the political state apparatus and organized crime.

Breach was targeted because she published names of traffickers—and those of corrupt politicians.

In a book recently published in Spanish, La guerra en las palabras, Zavala opens with the 2019 trial of El Chapo. Despite its billing by international media as the “trial of the century,” Zavala writes that the real power was elsewhere—with the politicians whom El Chapo bribed, and the politicians who work for narcos or are narcos themselves. The narrative of the war on drugs is a cover that allows the Mexican government to kill, torture, and disappear its citizens with impunity.

When Mexico’s new president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, known as AMLO, was elected in 2018, he promised “hugs, not bullets.” But the disappearances and deaths continue. Though AMLO promised to rein in the military, since taking office he has done the opposite. In January, the Mexican military mobilized more than 3,500 troops to capture El Chapo’s son, which resulted in the deaths of ten soldiers and nineteen alleged cartel members.

We still don’t know whether the 2008 crash was an accident or foul play. What we do know is that narcotrafficking has reached the highest levels of the Mexican government, as well as the DEA. Genaro García Luna, a former cabinet member in charge of public safety under Calderón, was arrested in Dallas in 2019 and accused of taking fourteen million dollars in bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel. He is now facing up to twenty years in prison. José Irizarry, a former DEA agent who embezzled millions of dollars in government funds and laundered money for the drug traffickers he was supposed to be investigating, was sentenced to twelve years in prison in November 2021. “The drug war is a game,” he said before he went to jail. “A very fun game that we were playing.” García Luna, Irizarry, and El Chapo may all be out of the game for now. But new players are surely lining up, just behind the screen.