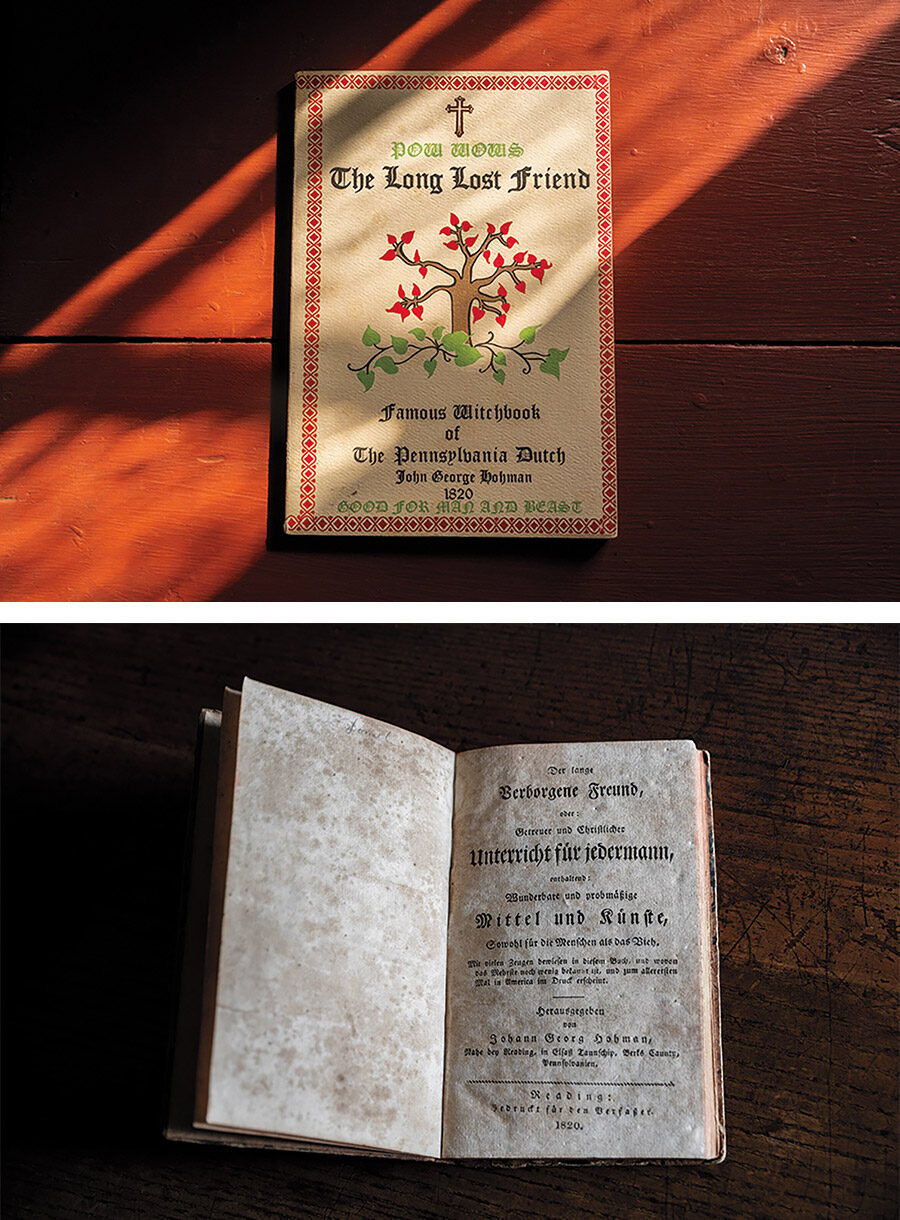

Top: Rachel Yoder’s copy of The Long Lost Friend. Bottom: A first edition of the book from the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University. All photographs from Pennsylvania, May 2023, by Sarah Stacke for Harper’s Magazine

And so I found myself at the door of an old woman’s shady house, a house I had tried to dream, had inquired about in emails, how to find and where exactly. Red brick, they said. Maybe rottweilers for sale? Look for it west of Intercourse, Pennsylvania. On the way, I read all the signs: doll outlet—5,000 dolls, country knives, buggy rides.

Through her side door, a darkened kitchen, for there was no electricity and the day was dull with a gray blanket of clouds. A long green counter extended across one wall and, at its center, a spigot’s dripping thudded into a wide porcelain sink. Bookshelves lined the rest of the room, packed with bottles of every imaginable herb, vitamin, supplement, tincture, oil.

I stood in the doorway and watched as the old Amish woman in a black dress sat next to another Amish woman, who stood in her own black dress. The old woman in the chair used a small, brown glass bottle to trace the contours of the other woman’s body, inches above her dress. Two introspective Amish girls in gem-tone dresses sat by a window, watching.

“Is it okay if I come in?” I asked, but I couldn’t quite hear what the old woman said—she didn’t halt her movements, barely turned to look at me—so I lingered in the doorway. She inhaled sharply, gasped, hiccupped, the brown bottle now paused at the woman’s lower back, then again near her liver.

“See, that’s where you have the pain,” the old woman said.

“Yes,” the other woman said. “I do have it there.”

“You have mold on your hip,” the old woman explained. She moved the bottle to the hip and gasped for emphasis. Her head kicked back. She bounced her knee, her whole body contorted, as if choking, or seizing, shaking off an unseen force. The old woman again said something to me that I couldn’t hear.

“Should I come in?” I asked. She gargled incomprehensibly. The window by the table was open and, on the nearby road, trucks shifted into low gear. Time either didn’t pass or had never existed at all. I stood in the doorway for hours, for entire days.

“Come in and sit down,” the old woman finally said, clearly, and I did, obediently, sit in one of the four mismatched chairs positioned in a semi-circle around the table where she worked. The standing woman and sitting girls didn’t acknowledge me. I sat unspeakingly, hands in lap.

After more gasping and choking, knee bounces and head kicks, talk of electricity and mold, the old woman paused with her brown bottle and turned to me.

“Who are you?” she said.

Rachel Smoker’s yard

What the old Amish woman named Rachel Smoker and others like her practice is called, depending on whom you ask, powwow or Braucherei or pulling pain or active prayer or witchcraft or folk-cultural religious ritual, though Rachel Smoker would never call it any of these things. She prefers “natural healing” and “reflexology.”

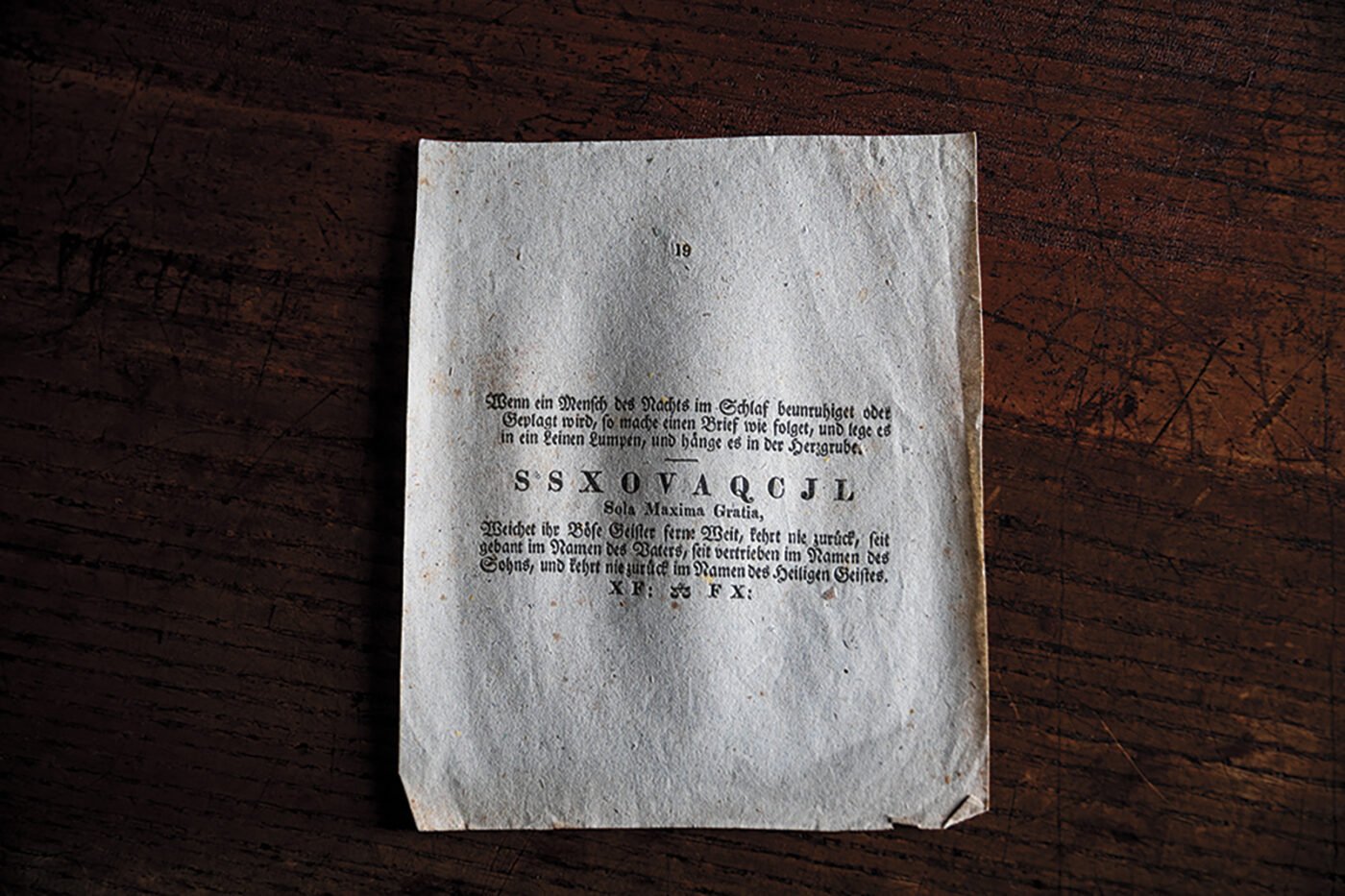

I came to find her because of a book of spells. And I sought out this book because it seemed to me one of the more compelling corners of my Amish and Mennonite heritage, though it had never once been mentioned to me growing up. The book—The Long Lost Friend: A Collection of Mysterious and Invaluable Arts and Remedies, also called the “Famous Witchbook of the Pennsylvania Dutch”—was compiled in the early nineteenth century by John George Hohman, a German-speaking immigrant. I’m an aspiring witch of sorts myself, so imagine my delight on reading the modern introduction:

Would you like to know the medicinal properties of peaches? An infallible cure for dropsy or Mother Fits? . . . Do you seek security against mad dogs, an incantation to prevent witches from bewitching cattle, and a means of preventing cherries from maturing before Martinmas?

Yes. I wanted to know everything.

The Long Lost Friend is not a book that anyone actually uses anymore, or perhaps ever really did. The practices and prayers of Braucherei have been passed down for the past three centuries via mentorships, with men teaching women and vice versa. Patrick Donmoyer, who directs the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University in eastern Pennsylvania, would tell me later that day that some consider Braucherei “to be a gathering of all those who ever were, who have ever participated in the ritual.” I see a green field and, on it, a congregation of hundreds, of thousands, standing silently in the setting sunlight. “I had one practitioner share with me that he was in the middle of doing something once, and he felt as if he could see the person who had taught him to do that particular thing, standing over, doing it to him,” he said. “And the person who had taught her. And the person who had taught her. And who taught her, and her, and her . . . And he said it was like a glimmer . . . ”

“I’m doing research for an article,” I had told my old Mennonite parents, after reading them a charm that involves the stomach of a black chicken and a bloodied piece of shirt worn by a chaste virgin. My father had never heard of the book and laughed at my spells, even though it was 2019 and the presidential candidate Marianne Williamson had just invoked “dark forces” during a debate. Despite his laughter, I asked my father if he would be my research partner as I sought out this local folk medicine. After all, he spoke Pennsylvania Dutch—a vernacular based on eighteenth-century German and used by German-speaking immigrants and their descendants—and still had relatives he kept up with who were Amish. He kindly acquiesced.

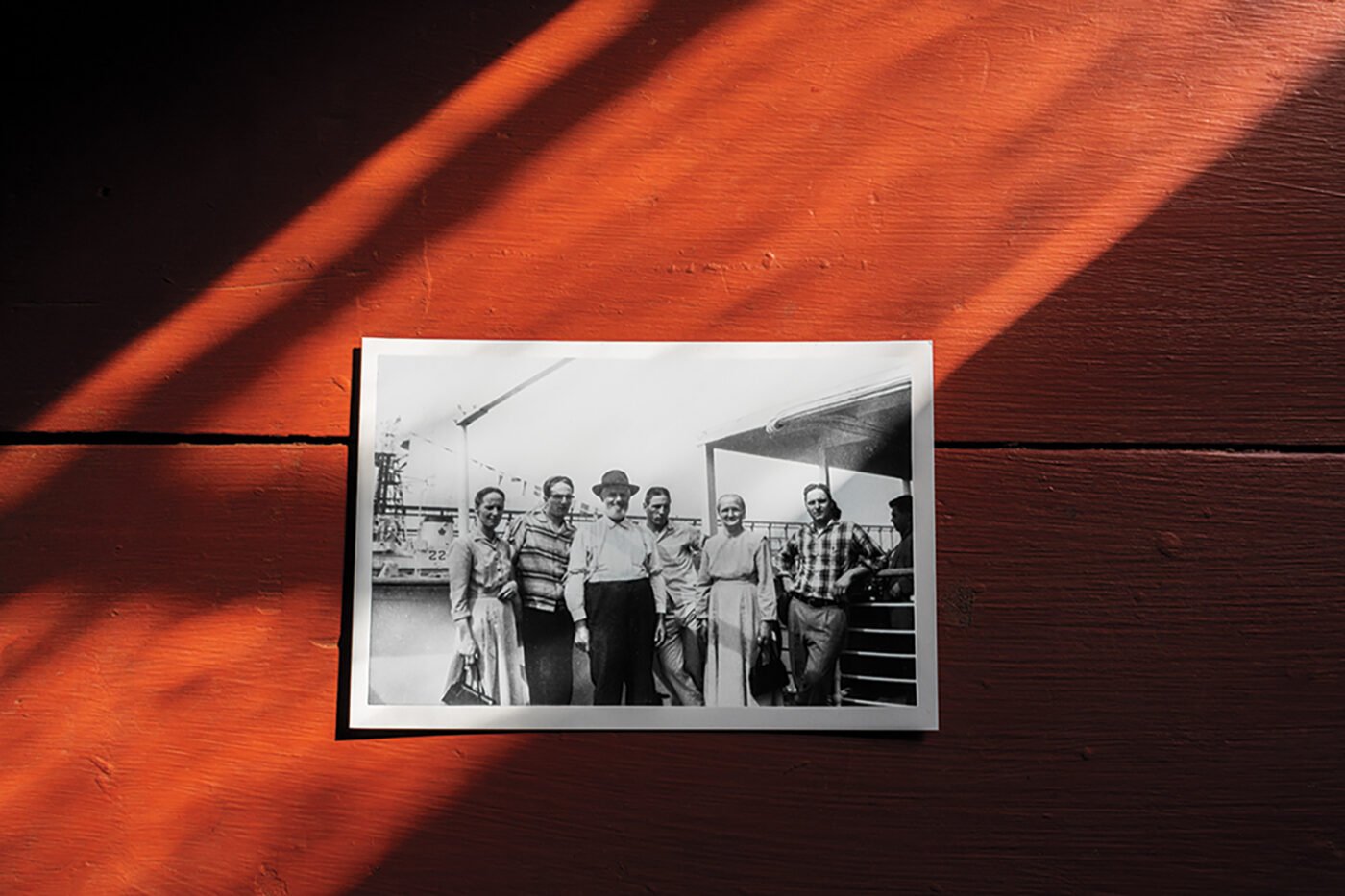

My father made the perfect research partner precisely because he knew how to move between worlds: His world had been a conservative Amish one, with twice-weekly church sessions and plain farm life. But then, come 1945, the drift began. My dad, his family: they were looking, out and around, toward this bustling modern world. “This all actually started with Dad,” my dad says. “Dad was a person who knew a lot, talked with a lot of people, had visitors at the farm from totally non-Amish backgrounds. He was very much aware of the world. That modernizing effect rippled through the family.” The ripple began when my father’s older, married siblings joined a Mennonite congregation. Though closely linked to the Amish theologically through their Anabaptist pacifism, the Mennonites were significantly more worldly, with their electricity, cars, and modern plumbing. And by 1951, John and Emma, my father’s parents, would also make the move to the Mennonite church. “What helped too is that in 1945 our house burned down,” my father says. “The community helped build a new house that summer—we took trees out of our woods for the lumber—and Dad negotiated with the Amish preachers that he’s going to put electricity in the house. They didn’t want him to, but he said he can’t build a new house and not put electricity in, and so they allowed him to do it. They tried to stipulate not more than one light at the center of the ceiling . . . ” He laughs.

In 1959, at age twenty, my father wanted to drift, too, enlisting in what he calls “alternative military service” via a Mennonite Church program named Pax. He would live in Austria for two years and repair bombed-out schools and churches. His father didn’t want him to go. He had lost another son, his namesake John Jr., who was a hemophiliac, in a softball outfield accident in 1950. “He felt he didn’t want to take that risk of sending a child to Europe at that time,” my dad explains. “I said, well, you left the farm, why can’t I?” So he left on the TSS New York. Sometimes I imagine he is still on this ship, floating far away on a field of mottled blues. Sometimes I think he never stopped sailing between worlds, is sailing still. Dad! I shout from the shore. Dad! Over here! But he is searching for a way home and it does not lead back to me.

New Bethel Church, founded in 1761, in Berks County

You have to understand that there is little to no desire among the Mennonites and Amish to discuss Braucherei, antiquated and fringe mumbo jumbo that is frankly embarrassing, especially with a forty-year-old woman who may or may not be Mennonite herself, with undefined intentions she claims have something to do with “writing about it.”

And yes, we could say this preoccupation with spell books has something to do with turning forty and the feeling a woman might have that the world is crashing down around her: She couldn’t have another child if she wanted to, and she did want to, desperately, at moments. Her body had begun to bleed early or late, too much or not at all. She ran hot. She wept. Her breasts hurt and her uterus hurt and she longed for another new, hopeful thing to squirm and swim inside her. But it was too late, too late . . .

Add to this what her father had been saying, which finally hit and stuck: her small son wouldn’t know anything of his great-grandfather’s world of buggies and farms. It would be completely lost within three generations—drifting, drifting. And her father was correct, because it was already almost entirely lost to the woman.

So she desperately tried to hold on, to her old father and the crashing-down world that was once Amish and her burning-up body that on her trip to Pennsylvania refused to bleed even though it was time. And what of her immune system, which now injudiciously attacks her guts and the bones surrounding her guts? Inflammation is the word, a cellular conflagration.

Why does her body think it needs to sear her in half? This question partly explains my preoccupation with the spells of my ancestors. But it also has something to do with the dreams about houses I’ve been having for decades. In one recent dream, I toured a house for sale that kept opening into more and more magical rooms: a kitchen with a glass ceiling and plants strung from the rafters and a little loft for napping while the soup cooked, and a living room with a full restaurant-style bar, and a shady Olympic-size pool tiled in elaborate retro patterns. Back at the front door, I learned from the realtor that the house had just been sold, and I sat down on a purple velvet stool to weep. But then an elderly couple stopped next to me. The old woman placed her hand on my shoulder and lovingly said, “Oh, don’t worry! In the end you lose everything.” And the truth of this flooded me with relief. Ahhh, yes. In the end, all is lost! What a relief. I’d been riding this feeling through the falling-down world of my midlife—through the too-lateness anxiety, this nagging dread I was some sort of fool, the bald facts of bad decisions—through all this I’d held fast to the joy of death given to me by the old woman, but then even this began to disintegrate, and the prospect of losing instead poured over me with horror, horror, horror . . .

So that’s how I found myself—before the trip to eastern Pennsylvania—back home in Ohio, where I turned to my parents’ old friends for my initial research. I began on a Hartville farm that looked like every farm I’d ever visited, a white house with black shutters, brick-red barns out back, a little model windmill at the head of the drive that would have delighted me as a child and still, as an adult, worked its charm.

Gertie “likes to talk,” my dad reported, and my mom informed me that Eli was “the nicest man.” This was a second marriage for both of them, as they’d lost their original spouses.

“It’s so nice they found each other,” my parents insisted.

Inside the white farmhouse, Eli, his tongue thick with a Pennsylvania Dutch accent, explained that his father was an Amish deacon who led services every other week. On the off weeks, his uncle Menno Wagner would go out and do his Braucherei.

“For instance,” Eli said from his overstuffed recliner, “he would take a baby who wasn’t growing and pass it through a length of string he had tied into a circle.”

“Well, did it work?” my dad asked.

“Who knows?” Eli replied exuberantly.

They all laughed.

Gertie’s dad sometimes did it for her sister, too, the “it” being this thing none of us really had a word for.

“You have to make a fire and get coal. Then you get an egg, put a string around it, and put it in the coals,” Gertie explained. And then what? We all shrugged.

But Gertie’s first husband’s father, he was something else, something Gertie didn’t feel comfortable talking about. She grimaced and rolled her eyes as she explained his “gift of healing,” his ability to use his body to draw out pain from others.

“He just put his hands on you, and you could actually feel the drawing,” she murmured. He became somewhat famous for it and would go on trips to Pennsylvania.

“He’d come back with hundred-dollar bills in his Bible. That’s where he kept them,” she said.

“People claim it’s electrical,” Eli added loudly. “The Amish are very gullible.”

“Sometimes he’d put his hand on someone and then burp,” Gertie said reluctantly.

I finally asked, well, what did his children, or your first husband, really think about the healing?

“They didn’t think about it,” she answered, as if this was evident. “They just went along.”

“Have you ever tried the remedies?” I pressed.

“No, I’d be afraid to,” Gertie said as she sank into her rocking chair.

A silence overtook us. The room bloomed with discomfort, as though I’d emitted an unspeakable odor.

“Jews have a long tradition that reasoned they didn’t go for Jesus because he used black magic,” my father chimed in. Water to wine, healing, all that. “If someone did that now, we’d kick them out of the community.”

They all laughed and agreed, then lit on what was actually real, namely water witching, a practice in which a person finds an underground source of water by using just the right tree branch to lead the way. All present confirmed this practice to be entirely legitimate.

“It’s even worked for me,” my mom, a former algebra teacher and perennial skeptic, admitted. She extended her hands in front of her as if being led to a source by the Holy Spirit.

It was at this moment that I feared my entire trip was doomed, that my subject of research was, in a word, silly, a bunch of quacks and hucksters pushing snake oil. I was tired. We all were. We hugged and noted our exhaustion, the prospect of another endless afternoon ahead of us.

“We have to do things for fun,” Gertie said, smiling as she gestured to Eli, who held laughter in his eyes, “so we sit here and try to decide who’s going to die first.”

The next day, we had an appointment with my dad’s Amish cousin Ella Schlabach, whose father, it’s rumored, was a Braucher. We drove just an hour from Hartville to Holmes County—Amish Country, they call it—the place from which both my paternal grandmother and grandfather hail. On the way there, my dad passed out, mouth ajar, in the back seat. And when we made a stop at the Amish & Mennonite Heritage Center near his cousin’s house, my mom asked, “How far does this seat recline?” and then lay there for an hour as my father and I wandered around inside. Soon it was lunchtime.

As I always am when we visit my motherland, and despite the alleged research, I was most interested in gastronomic conquests: noodles over mashed potatoes, peanut butter pie. Outside Boyd & Wurthmann Restaurant & Bakery, an Amish girl in a jean vest held a baby on one hip, a cell phone in her hand. Inside, we ate bread with apple butter, more bread, noodles, pie.

When we finally arrived at her farm, Ella was skeptical of me, as well she should have been. This woman in her black dress and white covering, relaxing in her rocker, really did not want to talk about her father and his faith healing and how he would “pull pain” from those who were sick and sometimes, after, get sick himself, so intense was the thing he had drawn from their bodies. No, there weren’t Brauchers anymore and, actually, her father really didn’t do it all that much, and would we like to see his library instead? We politely examined the dusty books in a darkened living room, admired the burgeoning houseplants, discussed the never-ending rain.

“Well, goodbye,” Ella said.

My ennui grew as we glided and dipped through the hills of Amish Country: small lives nestled in small valleys doing small things. And this is always the sense I have when I come back here, that I am slowly disappearing and, should I stay too long, will cease to be entirely.

I was raised twenty-five miles south of this disappearing place, not in a valley but on a wooded hilltop within a radical experiment in intentional Mennonite community. My parents had left Hartville in middle age to move to this place called Deer Spring, where they lived for thirty years. The thing about leaving home is that not many Amish or Mennonites do it, or at least they didn’t use to a generation ago, or perhaps it’s that within my father’s family it was seen as a betrayal, or maybe that’s just my father’s guilt talking through me. Whatever the backstory is, the fact of the matter is that I was raised at the dead end of a dirt lane in the dark Appalachian woods. None of the other parents had ever been Amish, so my father’s heritage represented an extreme of conservatism within the group. Add to this his seminary studies and voracious intellect and, it was clear, at least to him, that he should be the minister. But as is the way of egalitarian commune living, it was decided that all adults should take turns leading worship. My father had wanted to move to the deep hills and find a following and become a prophet. Instead, he was relegated to worship leader every six to eight weeks.

I’ve always thought of my father’s Amish childhood as a place to which he longs to return but doesn’t belong. His love and anguish over this paradox, whether purposefully or accidentally, he bequeathed to me. This way of living in community, of subjugating the self and its desires for this beautiful life, this is the way, the truth, and the light. This beauty goes back centuries, to Europe, to the first martyrs who gave their lives in the name of pacifism. Grow up and marry into the faith and continue on in this way. But you know what else is nice? Films. Literature. Philosophy. The symphony. My father and I are in agreement on this.

I didn’t want to be a wife or mother. They both looked like traps to me. I wanted to go to college and live in New York City. I wanted, I wanted. And I fell in love with this wanting. He was everything a Mennonite wasn’t. And in the throes of this love I made a choice to love away from my family, away from my upbringing, toward the American oblivion of self-actualization and dreams.

So I left. I am always leaving, even when I think I’m settled in one place. Yet now, in middle age, the comfort of return suddenly, stupidly, sparkles with hopeful novelty. What if? the child-heart murmurs. What if you went home and something miraculous happened? What if a witch? What if a spell? What if, oh Lord, dare I pray, what if happiness, not just for me, but for us all?

On the drive back to Hartville, pertinent to nothing, my dad says from the back seat, “I don’t fit in anywhere! I’m a resident alien wherever I go!” This, after we had just visited the one place on earth I would think he would feel at home. (Amen.) And I wanted to say to him what he had already said to me on this visit: If you believe in it, then it’s true. But I didn’t, because the sky was heavy with thick clouds and rain and the day was stuffy enough to smother, and I was sliding over hills and around sharp curves and passing buggies even though I couldn’t see what was coming from beyond the next knoll. The sky billowed gray and it rained and rained and rained. I was apart from my small son, and I felt pointless, purposeless. Everything was so heavy and, to be honest, I would have liked to close my eyes, too.

Back in the glimmer, Rachel asked, “How do you feel?”

White whiskers fuzzed her chin, her eyes bright after a recent cataract surgery. The smooth skin of her face plumped with preternatural hydration for a woman in her seventies. She no longer held the brown bottle but simply ran her open hands around my body. She cluck-cluck-clucked with her tongue when her hand passed over my liver.

“Do you feel warm?”

“Do you feel better?”

“Do you feel energy?”

“My body has a lot of electricity,” she explained—this electricity, or gift of healing, was revealed to her thirty years prior when her son, just an eleven-month-old baby, fell off the bed and went into convulsions. The family took him to the hospital, and after lengthy examinations—“Five doctors!”—there was nothing they could do.

Once home, the convulsions continued and the family, fearing the boy would die, took him to Sarah Glick, a local Amish healer. There, Rachel assisted Glick, already an old woman, who instructed her to hold the boy’s spine at the neck and the tailbone and, then, to run her electricity through him, to get his energy flowing.

He’s in his thirties now, Rachel reported, and “might be a little slower than some,” but was married and living his life. She said she should have continued but was just getting into the practice back then and didn’t keep up with it.

As Rachel treated me, my father wandered in speaking Pennsylvania Dutch, and Rachel brightened. After they exchanged pleasantries I couldn’t understand, she cheerily talked about pesticides and chemicals, how they are so hard on the body, how they are making everyone sick, how they’re in the well water now.

“Ach, yes,” my father scoffed magnanimously.

And on her farm, she continued, they cut the thistle in the meadow and then gave it to the horses. They would never throw it away like other farmers do! And when the cows eat it, they make more milk.

“Of course!” my father agreed.

She said these days people don’t have enough work. How work is both work and play. How you shouldn’t shy away from hard work because it’s what keeps you healthy.

“Most people have a blocked brain stem,” she went on, then asked me, “Are you tired?”

“Of course I’m tired,” I said.

“Young people like you didn’t used to be tired.”

“I’m not that young.”

“Well, yeah, but my children don’t ever get tired.”

She told my dad he had a healthy liver and strong genes, suggesting that I did not have a healthy liver or strong genes, because I grew up around so many chemicals.

She grew focused on my brain stem, on making sure it was open, kept telling me to “push the spot one inch from the spine and one inch from the hairline, right there in the middle,” then took me to a massage table in a back room where she pressed on that spot for five minutes straight until it was tender.

She exhumed a giant vibrator from some cabinet and, as she ran it over my back, said she liked Donald Trump because he’s suspicious of the medical establishment and supports natural healing and is against abortion.

“And we’re against abortion,” she said definitively. My entire body rumbled furiously. Between us, a silence dilated. My uterus ached. I was overheating. The old woman then assaulted my skull with her strong hands, pressing on either side of the back of my head. The pain grew inside the silence, stretching into a field of thick, unrelenting pressure.

“Do you feel that?” she finally asked, her hands hard against my skull. “I’m pulling the bones apart.”

On the way to find the old Amish woman in the redbrick house, my dad and I listened to philosophy podcasts instead of talking, because we only had the past to talk about and neither of us wanted to address it. Instead, St. Augustine posited, much to our relief, that the past and the future didn’t really exist. Voltaire: “What is optimism? . . . Optimism is the mania of maintaining that everything is well when we are wretched.” Michel de Montaigne: “To philosophize is to learn to die.”

In between episodes, my father wanted to know what comes first: knowledge or faith? But I wasn’t altogether ready to expound on my epistemological opinions.

Well, how about materialism then? Would I consider myself a materialist, he wanted to know.

And yes, I am a product of our modern world. Yes, I believe in science, believe in the possibility of objectively knowing some very limited things, but also, sure, I get stoned. I can understand how the word “knowledge” is a slippery thing. I understand that particles operate differently on a quantum level than they do up here in this macro reality where we all live. I understand there are contradictions, and that knowledge is limited, and I’m no fundamentalist so, of course, there is knowledge but there is also mystery, both tangled up together. Sure, sometimes I have ontological insomnia because I don’t know where we are and what we are and why we are.

And then we were talking about God, and I asked him what he even meant by God, and he said God is the spirit, then paused. He looked fiercely at the oncoming road and opened his palms toward the icy air blowing from the vents.

“God isn’t a being up in the sky,” he said, voice rising, “but God is, instead, a force we move into as we go out into the world. You move into it.” He pushed his hands toward the window, the horizon.

We were silent, driving up into the Appalachian Mountains, swells and swells and swells of green, the mountains my own ancestors passed over as they moved west to settle in Holmes County. My father thinks that God, that this spirit we walk out into, is inherently good, and this I very much would like to believe.

We talked about God because we did not want to talk about how I no longer go to church, how ten years ago I told him I didn’t believe in God, how twenty years ago I left home in love and on fire, causing extraordinary tumult, checked myself into a rehabilitation facility because I didn’t want to be alive and couldn’t articulate why, blamed my father for being too controlling and didn’t speak to him for months. We do not talk about how I have forsworn the Mennonites for decades.

It’s comforting to imagine that things go away if you leave them alone long enough. These are the questions I don’t ask my father: How did I hurt you? Are you still hurt? When you think of me, do you feel sad? Am I a failure? Can you forgive me? Can we be happy?

And these are the reasons for this trip left unarticulated: I am trying to get rid of this feeling that I am burning myself up from the inside out. I am trying to get rid of this pain.

But if there is not philosophy, there is only silence. If there is not talk of films or books, there is only an ever-expanding loss, of generations, of faith, of a daughter far from home and far from God, of a father from a different time and place, and of people slowly moving into the God of his understanding until, one day too soon, he also moves into God and is gone completely.

“Of course,” my father said, as we sped higher and higher, toward the clouds, “suffering is always the problem.”

Another way of telling the story: After Rachel pulled Rachel’s skull apart, Rachel held up a small brown bottle with the word bumps written on the label and told Rachel it was good for bumps. Rachel asked what she meant by bumps, and Rachel explained, you know, “if you bump your head.”

“I think every household should have a bottle of this,” Rachel said, but Rachel opted instead for her spinal blend, which contained olive oil, frankincense, lavender, wintergreen, and hemp. Rachel reasoned this would be good for her blocked brain stem.

“And how about this?” Rachel concluded, pulling a package of powdered beet from a plastic shopping bag tucked behind her chair. “It’s good in smoothies.”

In the end, for what amounted to a very light massage, a tiny bottle of olive oil, and a beet supplement, Rachel charged Rachel fifty dollars in cash. Rachel’s father handed over a twenty-dollar bill for his own small bottle of olive oil.

“No trail!” her dad said later, giddily, as he flicked his fingers midair. “Poof!”

“Do you have a car?” Rachel asked Rachel abruptly. She nodded. “Great, you can give me a ride home.”

At Rachel’s house, Rachel met Rachel’s daughter, Rachel.

“Three Rachels,” Rachel murmured.

If Rachel were smarter she might say something insightful here about the nature of reality. That experience is not so much an objective reality as a projection of the self. That as she moved into God, the Rachels around her multiplied, moments constellated in complex webs, and the people of our lives and stories began to stack on top of one another, until eventually, when she looked into one face, she was looking into every face: She was the middle-aged writer who had lost her history just as she was the opportunistic old woman who had built a business based on her electricity and then too her dubious daughter, confronting the opportunistic writer, protecting the electric mother. The Pennsylvania Dutch scholar reminded her of her autodidact father reminded her of the curious man she married reminded her of a long-lost friend. The old woman of the dream was the healer she would meet soon on this trip was the therapist she saw biweekly was the daughter she never would have. The glimmer.

When my father and I arrived in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, after the visit with Rachel Smoker, I handed Patrick Donmoyer a heavy paper bag of a dozen Amish cookies as thanks for his time before he showed me and my father around the cultural center. He spoke in encyclopedic detail as he took us through a stone farmhouse built in 1814, a summer kitchen, a little log cabin, a big red barn. We proceeded to the brick one-room schoolhouse, the crown jewel of the cultural center, inside of which were the sorts of things one would expect to find: rows of historically accurate desks, a blackened woodstove, a long slate chalkboard.

“Part of the reason I wrote a book was because I came across so many people who would shamefully explain to me that they had these powwow memories or that someone in their family did it, and they’d come to me asking, ‘What do I do with this?’ ” Patrick explained as we sat down to talk.

He told me about his grandmother, and the story she told him, about receiving powwow: “She had a wart on her hand and her grandfather powwowed her wart away” by rubbing it with the cut side of half a potato, then burying the vegetable whole under the downspout of the house. “And he did this during the full moon, and she remembered the moon and she remembered the potato.”

And then he was on to his great-grandmother, who was also a powwower, who in turn lived beside a famous faith healer—everyone back then knew someone who did powwow or had powwow done to them—and then used to put oil on her thumbs. “She would rub from the armpits down and then from the middle of the back down to the lower back and would recite this prayer. It’s . . . not just a prayer, because it’s not only primarily praying to divine forces and asking for intercession. It’s also creating a different kind of spiritual overlay to the illness.”

And I wondered what a “spiritual overlay to the illness” meant but we were moving, we were going, Patrick could talk, and he was talking about childhood household ailments, how powwow was used often for these, how it was and is practiced most commonly inside a single household.

“I powwow for my wife,” Patrick explained. “I powwow for my daughter, who’s two and a half, somewhat regularly.” Colic, he said, was called “liver grown,” and believed to be caused by the liver sticking to the inside of the body, and he began a prayer then, the same one his great-grandmother used to recite, in Pennsylvania Dutch.

“This would be repeated three times,” he explained, “and it means ‘liver grown, liver grown, go away from my child’s rib, just as Christ grew up and got out of the crib.’ And so there’s a metaphor. Previous generations of anthropologists would talk about the notion of ‘sympathetic magic,’ this idea that you invoke one particular scenario to create a similar kind of change in a certain circumstance.”

When he initially began learning powwow, he was tasked by his teacher with memorizing a wide variety of prayers and rituals. To do this, he attached visualizations to the words—an action, characters, a setting—and then inhabited the visualization as he recited his lines to his teacher.

“She also told me . . . that I was to do two things. One was to get an empty chair,” he motioned to the chair at the front of the room, “and do what I was taught as though I were imagining myself in the chair. But what came later was, okay, you’ve been practicing on yourself as if you were sitting in the chair. Why don’t you sit in the chair and project yourself outward and do it to yourself while you’re sitting in the chair?”

We talked objective reality. We talked Roman Catholicism and the medieval experience and “the World as emanation of the divine,” how when you “look at powwowing” and “you look at my great-grandmother’s liver-grown prayer” you were also looking at an “understanding of a divine truth,” looking at “Christ growing up and getting out of the crib” and a “dissolution of the illness. You’re essentially applying this kind of overarching sacred objective reality to intercess on behalf of this person, to essentially mitigate a disease.”

Ultimately it seems to me that what Patrick was saying is that to understand powwow you must understand that for the people who practice it and believe in it the only things that are objectively real are the things we cannot see.

“All I do is move my hands and say the prayers that I was taught,” he said, “and maybe something will happen.”

It was eight o’clock in the morning on an overcast Friday when my father and I pulled into a health and wellness center. After three days and two nights, we had finally checked out of the hotel and were on our way back home. I had an appointment to see one last powwow practitioner, but only because I had passed some undefined screening process in which Patrick vouched for me. To this day I find it hard to remember her name, as if it’s been scoured from my mind, and this forgetting somehow feels correct; out of respect for what she does and the privacy it requires, I won’t mention her name here.

Patrick had described this healer as “a really talented and interesting person on many different levels.” Inside the wellness center, she greeted me wearing a standard-issue massage apron, her silky, silver hair pulled back, emphasizing her pale, nearly translucent skin. She had the sort of wide-open, dark crystalline eyes that made a person feel self-conscious.

Outside her office hung a small quilt, three square feet. What was striking about it was its color palette, a departure from the customary Amish florals and sunshine. It was black on black on black, with just a few accents of evergreen and aubergine.

“A gift from an Amish client,” she explained as she ushered me into a darkened room. “Since I don’t accept payment for Braucherei, sometimes they give me things. They mostly come to have curses lifted.”

Inside the room, a small light above the sink glowed fluorescent. There were the expected items on the counter and side tables: bamboo, a small fountain, smooth river rocks, finger cymbals, tea lights. A tapestry on the wall featured peacocks and elephants, waves. We began with basics, namely why I was there, which I couldn’t really articulate other than to say I was on a research trip with my dad, to which she nodded, as if this was obvious.

The healer said she had long been interested in mystic traditions, and as we talked further, she mentioned that she could hear and see things other people couldn’t. In the near dark, she told me about the moment this power came to her. She had been working on the occipital intersection of bones at the back of the skull with a client who had an intensely traumatic childhood.

“We call these the gates to the soul,” she explained. “The portal for the etheric body.” While manipulating this particular place, she was ushered in an instant into the woman’s internal soul space.

“It was terrifying,” she murmured, a look of anguish on her face. “It was like being inside of someone’s nightmare.” Within her client’s fractured mind, she met its guardian, a being called Hala. The healer described her as a “giantess of the underworld” with a “pine-bark face,” a terrifying and powerful entity.

“Beings like Hala, that look the most ferocious, are in a place no one else can go,” she reasoned matter-of-factly. She raised her arm, finger pointed at me. “Hala presented herself to me. She said: ‘You don’t belong here.’ And suddenly I was back in the room, with my client. After that, when I was driving down the road on my way home, I could hear the conversations taking place in the houses I passed. And I could see spirits. I told my husband, ‘Look, if you need to commit me, do it,’ but he said, ’No, no. You seem to have a very clear hold on reality.’ So, I’ve learned how to live with this new power.”

She said she was ripped open and had to find a way to get her sanity back. “I have one foot in this world and one foot in that one.”

One foot in this world and one foot in that one. Your father was once Amish. He raised you Mennonite. He says there is no place in the world for him. Yet you were determined to be everywhere. You split yourself in two, in three, more, more, more to try to reconcile this: I can live at the dead end of a dirt road on a Mennonite commune and in a high-rise dorm at Georgetown. I can sing each part of “Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow” and dance at a debutante ball. I can work the clutch on the old tractor as well as I can drive this Mercedes down the narrowest streets. I will smile and agree with you while at the same time, elsewhere, when appropriate, speaking my mind. I will perfectly understand all worlds. I will navigate them with ease. I will only exist insomuch as other people do. I will only want in accordance with others’ desires. I will be a friendly ghost, all things to all people until, until . . . you are ripped open. You leave your family and your church and your traditions at twenty-one to wander the Arizona desert for a long, lonely decade, until you finally make your way here, to this room.

“I think you’re looking for a piece of yourself,” the healer said kindly, inviting me onto her massage table. As I situated myself, she explained that a person could have many “bindings”—her word for maladies, both of the physical self and of the soul. She wanted to perform a cord-weaving ceremony for me, a ritual which Patrick said “very few are still using or know about today.”

The healer began by placing a Bible under the massage table. She told me she was bringing my father’s spirit into the room, and I imagined it floating from his open mouth, there in the parking lot where he was no doubt taking a nap. After a moment, she told me he was floating above me, that she was mapping his body onto mine, and it was quite a thing to imagine: my father’s warmth just inches above me, the smoothness of his slacks, the smell of his day-old shirt. She began to sing then, low and lovely, in Pennsylvania Dutch. As she proceeded, the notes took on a tactile quality, a weight: dark birds moving through the night air.

She asked who, from my father’s life, once asked him, “Who do you think you are?” Who said that to him? Who was plaguing him with such an accusatory question? Was it a single person, or a group?

“Maybe his home community?” I said to her, a sadness sitting heavy on my chest.

She moved around me, hands weaving and unweaving unseen threads in the air as she sang, then chanted, in Pennsylvania Dutch and then in English.

“In the woods there is a red church,” she began, and I saw the woods and I saw the red church, and I felt the ripple of her words inside my fascia as they led me toward the door. “In the red church, there is a red altar. On the red altar, there is a red book. Open the red book and take out the knife. Take out the knife and cut the cord.”

She was disconnecting my father from the past. She was slicing him free of the judgment, the pain. She walked around me. She sang. She called on forces I would never fully understand. She made motions with her hands and the cords were loosed.

“This doesn’t always have a discernible effect, though I can see that it is having an effect on you,” she said, as tears trailed over my temples and into my ears.

When I returned to my father waiting in the car, he was reading.

“I finished a book and started a new one!” he said. “I had a nap!” Over two hours had passed, though I could in no way have estimated this amount of time. Forty minutes? A number of days? Who could tell?

“Did you get it done?” he asked with a smile, not visibly perturbed by how long I’d been gone. “What did you do in there?”

“I don’t know what I did in there,” I said. “How do you feel?” I examined his face for any signs of revelation or God, wondered what he dreamed about but didn’t ask.

“Fine,” he said. “Let’s go.”

We took off in high spirits toward home. We’d done it, though what exactly it was remained to be said.