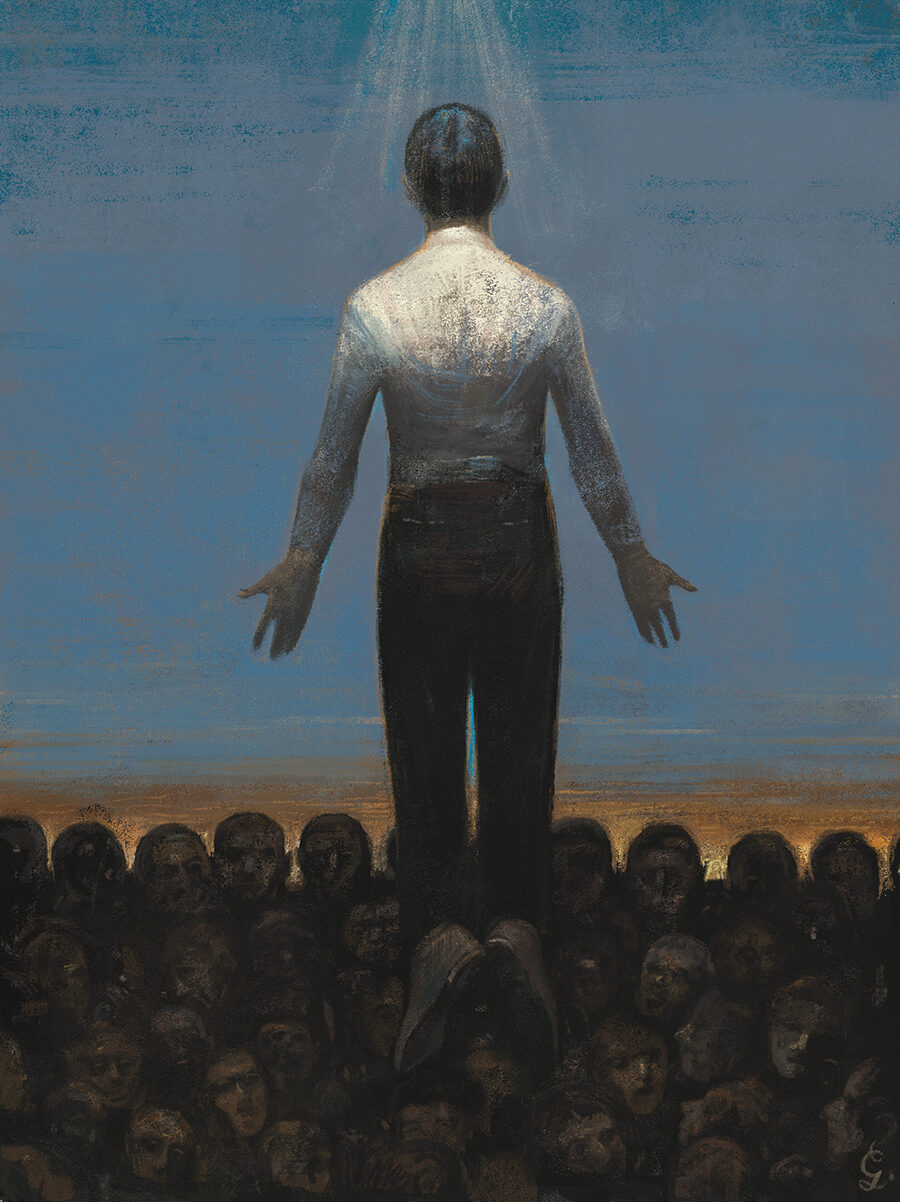

Illustrations by Gérard DuBois

Writing about “Woke” has at least two pitfalls. One is that any criticism of its excesses provokes accusations of racism, xenophobia, transphobia, misogyny, or white supremacy. The other problem is the word itself, which has been a term of abuse employed by the far right, a battle cry for the progressive left, and an embarrassment to many liberals.

No one can agree on what woke is supposed to mean. The right has blamed it for everything from the spike in school shootings to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, while many who are described as woke on the left…