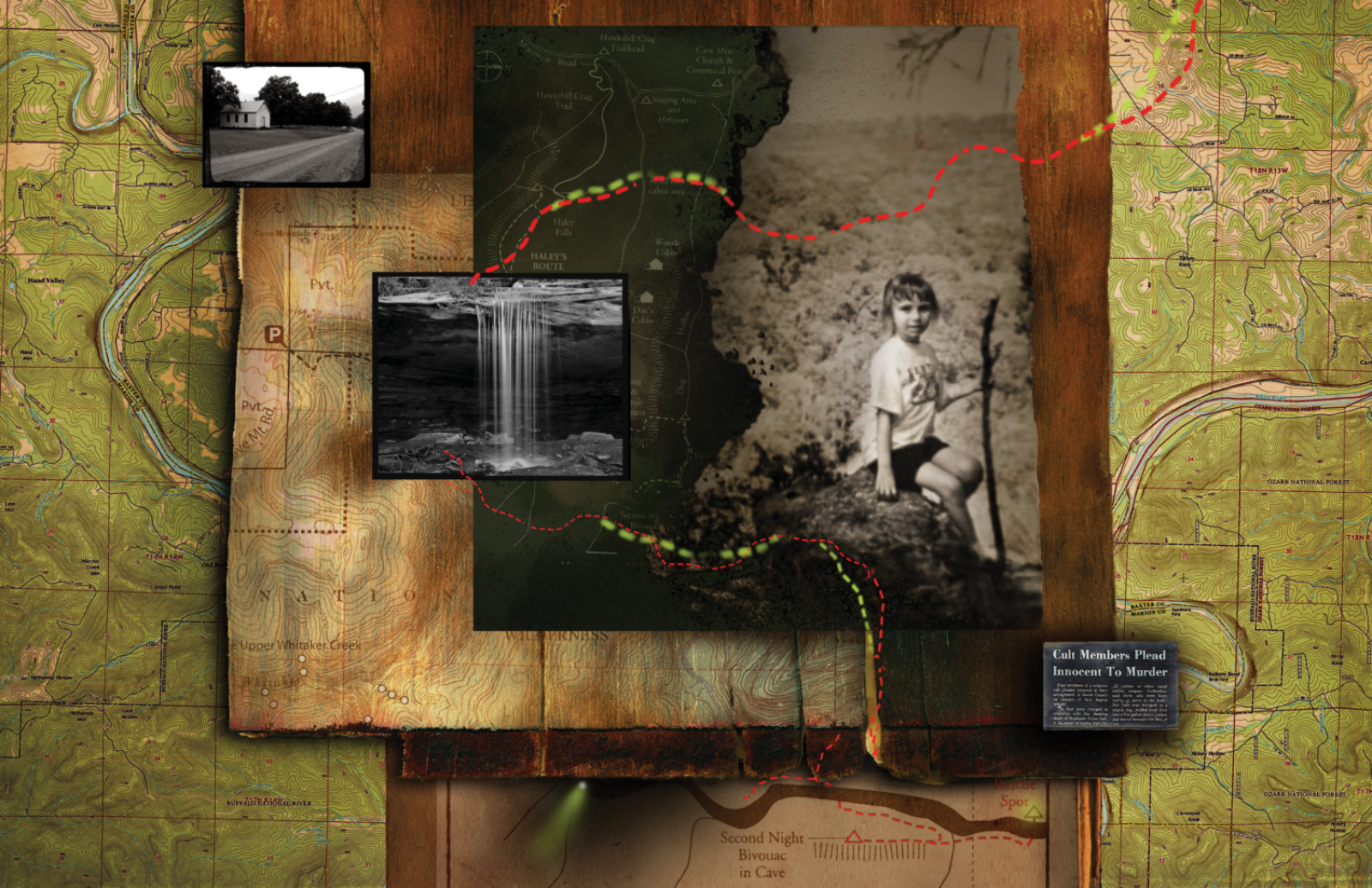

Collages by Jen Renninger. Source images: Cave Mountain Church © Tim Ernst; map of Haley’s route © Tim and Pam Ernst; map of Hawksbill Crag Trail © Danny Hale; Haley on the Hawksbill Crag Trail, April 29, 2001. Courtesy Kelly Hale Syer; Hawksbill Crag trailhead © Danny Hale; clipping from The Madison County Record, May 4, 1978

Twenty-two years ago, a six-year-old girl—my cousin—got lost in the Arkansas Ozarks, prompting what was at the time the largest search and rescue mission in the state’s history. Her disappearance would eventually connect my family to another story, a dark and bizarre one involving kidnapping, brainwashing, murder, and a cult that believed in the imminent end of the world, laced with the kind of eerie coincidences or near-coincidences that cause perfectly rational people to question what they think they know about reality.

On Sunday, April 29, 2001, Jay and Joyce Hale, my father’s older brother and his wife, took their granddaughter, Haley Zega—the only child of their only child—on a day trip to the Buffalo National River Wilderness in Newton County, Arkansas, in the heart of the Ozark Mountains. Jay was sixty-two years old, Joyce fifty-seven, and Haley six. That morning, Jay and Joyce had driven from their home in Pea Ridge to that of their daughter, Kelly, and her husband, Steve Zega, in Fayetteville, picked up Haley, and continued for about an hour and a half to a cabin on Cave Mountain, where a few others joined them: a lifelong friend of Jay’s named Claibourne Bass, and another couple. The plan for the day was to take a short hike down to Hawksbill Crag, a famous Arkansas landmark, continue on to another vista, atop a small waterfall, head back to the cabin, eat lunch, then drive a short distance down the mountain to meet up with a larger group at the Upper Buffalo Wilderness trailhead for an easy guided hike, hosted by the Newton County Wildlife Association, to see the mountain wildflowers then in full springtime bloom. They left the cabin for the first hike around ten-thirty in the morning. The wildflower hike was set to begin at one in the afternoon.

I should tell you a few things about these people, and about Arkansas. I grew up in Colorado, but both sides of my family are from Arkansas. My parents met in the Seventies at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. My father grew up in a tiny town in the Ozarks called Horseshoe Bend; my mother’s parents were from Paris, Arkansas, where her father was a coal miner for a time, and they retired in Rogers, just north of Fayetteville. Jay and Joyce lived about twenty minutes from Rogers on twenty-five acres of wooded land near Pea Ridge that the family nicknamed Hale Holler, where they had the office and machine shop that they ran their engineering business out of, their house, and another house they built for Jay and my father’s mother. Usually when people say they built a house they mean they had it built, but the verb is literal in their case. Jay also built motorcycles and guns, and got started on an airplane, and he invented the paintball gun (originally intended as an agricultural tool for marking trees and cattle), but never saw any profit from it—a good story in itself. The house he and Joyce built for my grandmother had a pneumatic elevator in it; in fact the elevator was the only way of moving between the first and second floors, and I was a little heartsick when, after my grandmother died, they had to replace it with stairs to get the building up to code to rent it.

Most of my fond childhood memories of Arkansas happened in Hale Holler: walking in the woods with Jay and Joyce, walking in the woods by myself, catching crawdads in the creek that ran through the property with my brother James and our cousin Ike. Anything else you need to know? That my grandmother taught me how to play poker, and my Uncle Jay taught me how to shoot a gun? That Joyce baked the cake for the wedding (well, one of them) of Alice Walton, the princess of Northwest Arkansas’s local royal family? I should probably also mention that my father was born when my grandmother was in her forties, by far the baby of the family—Jay is nearly twenty years older than him. I think it also helps to know that Jay and Joyce have been politically engaged and civic-minded people all their lives; Jay served as a volunteer firefighter in Benton County and even ran for office a few times. Kelly’s husband, Steve—who a few years after all this happened was one of many National Guardsmen sent to Iraq—served as a justice of the peace for nine years.1

I should also emphasize the extreme rusticity of the area where Jay and Joyce went hiking with their friends and granddaughter that day. The entire population of Newton County is about seven thousand. There used to be more people living in the Buffalo River valley; in the Sixties the Army Corps of Engineers drew up plans to dam the river for a hydroelectric plant that would displace much of the populace, but local conservationists rallied against it, instead allowing the National Park Service to acquire the land in 1972 and convert it into the Buffalo National River Wilderness, now a protected area. Basically: at first the few people who lived in that valley were informed the government would be building a lake on top of their houses, and then the great solution the conservationists came up with was to make it all government land, which meant they had to move anyway. There are longstanding tensions between local residents and the government, which they regard as meddlesome, untrustworthy, and incompetent. Keep that in mind for later.

This story begins on top of Cave Mountain, which is traversable by one narrow dirt road: Cave Mountain Road, which turns off of Arkansas Highway 21 just north of a bridge over the Buffalo River, and winds southwest up the mountain and back down the other side to Arkansas State Highway 16. The Hawksbill Crag trailhead sits at about the highest point on the road, and the trail leads from the road into the woods down the mountain a little way to a fork. If you’re coming from the trailhead, the right tine of the fork leads a short distance to a creek and a small waterfall, where the creek you just hopscotched across spills over the shelf of the bluff, and you can stand at the top of the waterfall and take in a magnificent view of the Buffalo River valley. The tine on the left leads along the bluff overlooking the valley, and from there it’s about half a mile to Hawksbill Crag: a dramatic arrow of rock jutting into the air a hundred feet above the forest below. This is the thing you have probably come to see, or rather the majestic view of the valley visible while standing on it, as your friend takes a picture of you. The path continues on, hugging the crest of the bluff, getting narrower, rockier, and scarier. When I hiked it in mid-December, there were points along the way that looked so precarious—in a few places you have to walk through small streams over slippery rocks at the very edge of the cliff—that I thought it safer to bushwhack a little farther up the mountain, cross the stream at a less deathly place, and bushwhack back down to the trail. I was glad none of the friends I grew up hiking Colorado’s mountains with were there to see me, but I felt like less of a coward for detouring around the diciest-looking spots when I later learned of the local notoriety of this trail’s treacherousness—google “Hawksbill Crag + fall + death” and you’ll get a sense: a death every few years, most recently in 2019 and 2016. As it winds north and east along the bluff, the trail gets thinner and thinner, less and less there, until it comes to a tree stump with a metal private property—no trespassing sign fixed to it, and a muddy laminated piece of paper I found lying facedown in the leaf litter beside it that reads

NOTICE TO HIKERS:

This trail DEAD ENDS

at Private Property ahead.

It DOES NOT loop back to the trailhead!

In order to return to the trailhead you need to turn around and hike back out the same way that you came in.

If you proceed in this direction you will get lost, and will hike farther than you need to.

Thanks!

I picked up the laminated paper, wiped some mud off of it, pinned it to the metal sign, and that’s as far as I went.

On that April morning in 2001, Jay and Joyce and their friends did not come to Hawksbill Crag as most hikers do, from the direction of the trailhead; they came the back way from the cabin, beside the private property that sign is warning you not to trespass on. They set out from the cabin—owned by a retired anesthesiologist called Doc Chester—hiked south and west on the scraggly footpath that becomes the Hawksbill Crag Trail, oohed and aahed atop Hawskbill Crag, then continued along the bluff to the fork and reached their terminus at the top of the waterfall.

Now, a waterfall is majestic to behold, but only if you’re standing at the bottom of it. Apparently there is a way of scrambling down the rocks on the other side of the creek to see the waterfall, and another way that involves climbing down a certain tree on the lower shelf that you can get to from the upper one (that’s the way Jay got down that day), either of which is for the advanced-level hiker only, which Jay certainly was, and six-year-old Haley certainly was not. Jay made it down to the lower shelf to the bottom of the waterfall, saw it, and climbed back up, while everyone else stayed on top, resting and taking in the view. It was about a quarter to noon. Hiking to the crag and the waterfall had taken a bit more time than they’d expected, and if they wanted to get back to the cabin, eat lunch, and make it to the group hike to see the wildflowers, they had to get going ASAP, and make a little hay while the sun shined, too. Everyone started back up the trail the way they’d come, but Haley was steaming with jealousy.

Child and grownups were at an impasse: Haley wanted to see the waterfall, but it was time to go. She sat down on a rock at the top of the waterfall and refused to move. She said she wanted to be carried. She was being difficult. She was being childish. She was a child.

Joyce told the others to go on ahead back to the cabin and fix lunch—she would stay behind and deal with the kid problem. The others headed back up the trail, though Clay stayed behind to keep Joyce company. Now it was three: Joyce, Clay, and Haley on the rock, unbudging.

After many minutes of Joyce’s exhortations had failed, Joyce and Clay resorted to the nuclear option of getting a child to do something she doesn’t want to do: play upon the fear of abandonment.

“She was sitting there and pouting,” Joyce says, “and I said, You sit right there so I can tell your mother where you are when she comes to get you. We’re going. Huff, huff.”

Then: walk out of sight and wait. You have to wait kind of a while, because if this trick is going to work, it has to work the first time. If you go back too soon, she’ll know you’re bluffing. And eventually, Haley came—begrudgingly, defeated, saddest, angriest little girl in the world, her mood probably spoiled for the rest of the day, lunch and beautiful meadow full of wildflowers tainted with a petulant drop of poison. But she came.

Good—we have movement. Clay and Joyce continued up the trail until they were again out of sight, stopped, and waited. Haley, again, dawdling, eyes downcast, face leaden with despair, emerged. Clay and Joyce continued up the trail around the next bend, stopped, and waited.

A long time passed.

Joyce told Clay to go ahead and join the others. She was going to have to go down there and drag Haley back by a rope or something. Clay left. Joyce went back.

Haley was gone.

Having seen the place, I am still a bit baffled as to how Haley got so lost so fast. At the fork in the trail, one way goes to the waterfall, one leads along the top of the bluff to Hawksbill Crag, and one leads across the creek and up the mountain to the trailhead on the road. Granted, I saw it in winter, when the nakedness of the trees affords much more visibility. They were there at the height of spring, when the leaf cover makes dark, narrow corridors of the trails, and a shout only carries perhaps ten or fifteen feet.

Joyce went back down the trail to the waterfall: no Haley. She did not even begin to tingle with panic until she hiked back up from the waterfall and saw the fork. Was this fork in the trail in-between the last place Haley had shown herself and the last place they had stopped to wait for her? She had thought they’d passed it, but now she wasn’t sure. She turned left and went up the trail that leads to the trailhead, shouting her granddaughter’s name. From this moment on, Haley’s name would be shouted in the woods by ever more and more mouths. Haley did not appear to be on that part of the trail. Eventually Joyce ran into two hikers coming down from the trailhead. They had not seen a little girl on the trail.

Soon Joyce and those two hikers and, in a short while, Jay, Clay, and the other couple were all spread out along the trail looking for Haley, wildflower plans now definitely scrapped, shouting her name into the thick, muffling foliage.

Joyce called 9-1-1 from Doc Chester’s cabin, and before long, Cave Mountain Road—a rocky, muddy, badly rutted dirt track so narrow that for most of its length, when two cars pass each other, one driver has to stop and let the other carefully squeeze around—was clotted with emergency vehicles rumbling up and down the mountain. Haley’s parents, Steve and Kelly, got there as fast as they could, joining the Newton County sheriff’s officers, police, other emergency workers, locals with no connection to my family, and friends and relatives who had come from all over. I was a senior in high school at the time, out in Lafayette, Colorado; after a sleepless Sunday night and a useless Monday with still no sign of her, my parents told me to take care of my brothers—five and fifteen years younger than me—while they took off in the car for Arkansas. Not far from the Hawksbill Crag trailhead is a cemetery and a tiny church—and I mean tiny: Cave Mountain Church is basically a one-room box smaller than some wealthy people’s bathrooms I’ve seen, with windows, a door, a pulpit, and two rows of five pews. This church and its dirt parking lot the authorities—there were so many organizations and agencies present (sheriff, local police, state troopers, park rangers, the National Guard—the full list runs two pages long) that I get them confused, so I have settled on the catch-all “authorities”—turned into the “command center” where the many volunteers were told to report.

“As far as I can remember,” said Arthur Evans, a family friend who helped with the search, “the official searchers had all kinds of fancy stuff to find somebody in the woods, including a helicopter with heat sensors that would, of course, mostly be useful at night.” There were other “gizmos,” as Art called them, including a computer program into which authorities plugged Haley’s biometrics—six-year-old, forty-nine-pound female—along with a topographical map of the area, which the program somehow crunched to arrive at the statistically optimal places to look. By dusk two helicopters were thudding across the valley. They would take off and land in an open field not far from the church, adjacent to the private road that leads to the cabins from which the hikers had set out for the bluff that morning.

At the end of that private road, Tim Ernst lived in a house perched on the crest of the bluff. Ernst is a photographer, nature writer, and blogger—his blog and the house shared a name: Cloudland—and he opened his home to Steve and Kelly and others close to them for the next two nights and days. Cloudland became the second hub of the rescue mission, and Tim later wrote and self-published a book about the ordeal, The Search for Haley, which you should check out if you want a much more detailed account of this part of the story.

The following night, day, night, and day passed as you can probably imagine: sleeplessly—especially for Steve, Kelly, Jay, and Joyce—and sick with terror; in logistical clusterfuck and general chaos; authorities scrambling to organize everything; more and more volunteers showing up to help and getting pissed off that they weren’t allowed to do anything. Every civilian volunteer I talked to told me a version of the same story: rushing up the mountain as soon as they could—many camping in tents or trailers, as accommodations in the handful of cabins quickly filled to capacity—and then “checking in” with the authorities, who told them to wait.

Many volunteers didn’t know my family; they were just locals who’d heard the news and had come to help. One of these was a sixty-four-year-old man named Lytle James, who’d lived in the area all his life and frequently tracked and hunted in the Buffalo National River Wilderness. Lytle James was about as local a yokel as you could get. (He has since died.) Sometime on Sunday afternoon, James went to the command center, offered his services, and was basically told to either go away and let the professionals handle this or sit and wait for the professionals to tell him what to do. He hung around feeling useless for a while, until he got frustrated and left.

It so happened that Lytle James’s son, Vixen James, served alongside Haley’s father in the Arkansas National Guard. Steve and Vixen had been at their annual training at Fort Chaffee near Greenwood, Arkansas, when Steve learned that Haley was missing. Steve of course left right away. Soon after, Vixen and Wes Hilliard, a Guard chaplain, drove out to Cave Mountain, arriving at Cloudland before nightfall. They helped with the search on Monday, and that night they drove out to Vixen’s father’s house near Mt. Sherman to shower. Lytle James told his son about trying to volunteer and almost as good as being told to go home. Vixen urged his father—who’d spent his life in that wilderness and knew it better than just about anyone, and besides was an expert hunter and tracker—to look for Haley on his own. The next morning, Wes and Vixen returned to the main search area on top of Cave Mountain, and Lytle James, along with his neighbor and frequent hunting buddy, fifty-one-year-old William Jeff Villines, saddled a couple of mules and set off for the low ground along the banks of the Buffalo River.

The authorities—many of whom were not on the clock, all of whom were doing their best to find and rescue my cousin, and none of whom I am in any way trying to cast as the inept and blindly-arrogant-in-their-trust-in-technology-and-especially-in-their-own-authority villains in this story—were pretty well convinced that Haley was either still on the bluff or somewhere above it, or else was a corpse at the bottom of it. On all sides, the bluff is a steep, rocky, nearly vertical wall of boulders; they did not think she would have ever even tried getting down it, and she certainly could not have gotten down it any way but falling off. So they’d decided from the beginning that looking for her below the bluff was mostly a waste of time. Almost all of their search efforts were concentrated along the bluff, inside the roughly three hundred acres of woods between it and the road, and on the mountain above. The Sheriff’s Office also searched for her with K-9 units: dogs were given a scent from Haley’s clothing and her security blanket, which had been sitting in the cab of Jay and Joyce’s F-150 since Sunday morning. Some of the dogs picked up the scent—maybe—and, starting from the place she’d last been seen, led their humans on a winding path through the woods right to the edge of Cave Mountain Road, where they lost it.

That was the moment when things turned a lot darker, as some began to fear that the reason they had not found Haley was that she was not there. That a driver on that road had picked her up and taken her.

On the night of Haley’s disappearance, a sheriff’s deputy approached Kelly to say that Colleen Nick had called and asked to speak with her. Colleen Nick’s daughter, Morgan Nick, disappeared near a Little League game in Alma, Arkansas, in 1995 and has never been found. In the aftermath of her daughter’s disappearance, Colleen founded the Morgan Nick Foundation, which “provides a support network to Arkansas parents and families of missing children.” The Nick case had briefly blossomed into a media obsession, especially in Northwest Arkansas. Kelly happened to be home on maternity leave that summer, and she spent much of it watching TV while nursing her newborn daughter, Haley; she’d followed the story closely and knew all about Colleen Nick. But her first reaction to hearing that Colleen had called was anger. “I’m like, Haley has not been abducted, so why are you calling me?” Kelly told me. “I felt like by her calling, she was somehow implying that Haley was truly disappearing.”

But she sat in the sheriff’s car, which had a mobile radio phone in it—definitely no cell service on Cave Mountain, then or now—and talked with Colleen Nick, and was surprised by what a calming and comforting voice hers was amid the panic and chaos of that first night. Colleen Nick drove up to Tim’s house and spent the next two days by Kelly’s side. On the morning of the third day, Colleen Nick accompanied a law-enforcement official who took Steve and Kelly aside and, Kelly says, told them that “they were shifting from a search and rescue to potentially a criminal investigation at this point.” Colleen and the officer furthermore recommended that Steve and Kelly speak at a press conference.

Colleen prepped Kelly for it, telling her (again, per Kelly) that she’d been “too tough and too strong and too stoic for too long in this situation. There is nothing stronger and more understood by people than a bond between a mother and child.” She needed to show emotion. “I now see exactly what she was telling me,” Kelly says, “and why she was telling me to lose it and cry on camera, and stop being so strong and stoic and upbeat about everything: Because people are not going to believe you. They’re gonna think you had something to do with this.”

So she did “lose it and cry on camera.” Colleen introduced them, then Steve spoke, and then Kelly, who ended the press conference in tears, holding Haley’s security blanket, making this plea:

And so, if anyone knows where this baby is—I don’t care how you know, how you find her, why you have her, where she is—it doesn’t matter to us. We just want her back. She is the most important thing to us in our entire lives, and we would give up everything that we have to have this baby back in our arms, and to put this back in her hands. And I would just plead that you would put her back with us.

Earlier that morning, Lytle James and William Jeff Villines had packed a bunch of snacks they thought a six-year-old girl might like—little plastic tubs of chocolate pudding and, weirdly, some bottles of Diet Coke—plus a camera to document it in case they found her. Riding mules named Copper and Big Mama, they went looking for Haley along the bank of the Buffalo River. Some months after this happened, Dateline NBC aired an episode about it, which includes this exchange between James, Villines, and the Dateline anchor Rob Stafford:

lytle james: When the government gets involved, and the news media gets involved—you know, we didn’t want to go gettin mixed up in that. We didn’t know what they was plottin out, but we knew what we could do.

rob stafford: You’re saying you have more trust in yourselves than you do in the media and the government?

william jeff villines: Well, for one thing, they was tellin you where to hunt.

The two men on mules clopped alongside the river from early in the morning until 1:30 pm, when they stopped briefly to eat lunch, and then continued on for another half hour, at that point growing doubtful they would find her. But around 2 pm, when they came near an alcove of the Buffalo River valley about 830 feet below and two miles north of the main search area, they saw the six-year-old girl sitting on a rock beside an inlet of the river with her shoes and one wadded pink sock next to her and her bare feet in the water. The plastic tubs of chocolate pudding and a bottle of Diet Coke were the first sustenance she had taken in since before she went missing. She wasn’t quite fifty pounds when she got lost, and she’d lost seven of them by the time she was found.

“I remember sitting on a ledge, by the river,” Haley told me recently. “And then I see the mules, the people on the mules, William Jeff Villines and Lytle James, and they came up to me. People ask me all the time, How did you know that they were okay? How did you know you could go with them? I didn’t have a choice. It was people.” Villines and James approached and said, “We’ve been looking for you—you’re that little girl, and your name is Haley Zega.” Then they gave her chocolate pudding and Diet Coke. “I remember he carved a spoon for me to use out of a little sapling. A little makeshift spoon. They brought me snacks, because they knew they were going to find me. Even though they were not looking in the area that the official search party had deemed where they should be looking. So, honestly, it’s such a miracle that they found me, because nobody was looking for me there except for them.”

Stopping periodically to alternate which mule they put Haley on so as not to overburden either animal for too long, Lytle James, William Jeff Villines, Copper, and Big Mama carried Haley another three hours beside the river and up the mountain to Cave Mountain Road, where they handed her off to the authorities.

Tim Ernst spent that summer doing a lot of sylvan detective work, trying to figure out where exactly Haley went. He thinks he more or less figured it out, and I defer to him. If you come up Hawksbill Crag Trail from the waterfall heading north, you will see the fork—the path on the left goes to the trailhead, and the one on the right leads along the edge of the bluff, passes the crag, and continues on from there until it veers left away from the cliffs and basically disappears into the forest floor to the untrained eye (Haley’s eye was not trained). But right after that fork, there are several places where the trail splits briefly and then rejoins itself. These slight deviations run so close together that people hiking on the two briefly parallel trails would clearly see each other. But again, it was spring, the vegetation was thick, and Haley was a very short person.

Tim thinks Haley might have taken one of these side trails and somehow walked right past Clay Bass without either seeing the other. Or perhaps Joyce and Haley passed each other this way, and Clay, with his adult legs, was ahead of her, and she never caught up to him. He believes that while Joyce was searching for her on the part of the trail that leads to the trailhead, Haley kept following the other part of the trail along the bluff, passing the crag, and then continued on, missing the place where the others had turned left and headed up to the cabin. She kept on going, following the trail past that no trespassing sign and onto Tim’s property, and must have passed very close to his cabin. At some point she started following a tiny game trail that led her to a part of the bluff a good ways north of Tim’s cabin where the angle of the slope becomes obtuse enough to climb down into the valley. Haley is certain she climbed down the bluff that first day, blindly pushing through dense wilderness until she reached the Buffalo River.

“I didn’t know that there was a river,” Haley told me. “But I got down the incline, I walked a couple of yards, and all of the sudden through the trees I remember seeing—I probably heard it first—I could hear the water, and then I remember seeing it through the trees, and seeing the light shine off the water, and I was like, Okay, river. So I went to the river.” If Tim’s detective work is right, the route she walked from the waterfall to the river on that first day is only about two miles, but the last half mile of it involved climbing down a precariously steep and rocky slope. Hearing the river immediately after determining she had reached the bottom of the slope maps onto the terrain pretty well: Cave Mountain shoots upward directly out of the west bank of the Buffalo.

Down in the valley, she noticed helicopters flying overhead. “I didn’t know if it was normal for helicopters to be flying over the forest. I didn’t know they were looking for me. I just thought, okay, well, if there are helicopters, it would probably be good if they could see me.” She shouted her name, threw sand in the air, but no one spotted her. “My plan was: rivers always eventually lead to a bridge, or civilization. So follow the river, it’ll lead to a bridge, it’ll lead to a road, the road will lead to a gas station, and I will call my parents. That was my plan as soon as I found the river: follow the water.”

She started walking along the river. Incredibly, she swim-waded across it several times—in April, when the water is at its deepest and the current at its fastest. She believes she was walking in the same direction the whole time, but it’s possible—especially considering she did not eat or drink anything for nearly three days—she got turned around in a delirium and doubled back over the same ground more than once. Most of the ground she covered was on that first day: the place where James and Villines found her is less than two miles north of the spot where Tim thinks she reached the river. She spent the first night lying on a flat-topped boulder in the middle of the river. She wanted to be in the most visible place possible for the helicopters to see her. The helicopters—equipped with heat sensors—were indeed flying back and forth over the valley all night, but they never spotted her. When the sun rose, she climbed down from the rock and kept walking beside the river. When night fell on the second day, and there was a hazy ring around the moon, she remembered her mother telling her that was an indication of rain. So she climbed a little way up the mountain on the east bank of the Buffalo and took shelter in a small cave—not even a cave, really, more of a divot in the rocks, enough of a ceiling to keep the rain off. The sun rose again. “And then the third day it was more of the same. Just kept walking.” At some point she began to hallucinate. “When you start to starve, when you start to dehydrate, people hallucinate all the time. I hallucinated people in the trees. I hallucinated family members. I hallucinated a valley full of flamingoes. I just remember coming around a bend in the river, and the flamingoes were everywhere.”

Lytle James and William Jeff Villines found her at around 2 pm on that third day—about the same time that Kelly was up on top of the mountain, pleading into TV cameras with an imagined child abductor. Haley was reunited with her par- ents at around 5:15 pm. An ambulance took the three of them to the North Arkansas Regional Medical Center in Harrison, where Haley was treated for dehydration. There was nothing else wrong with her, and the hospital released her the next morning.

The waterfall where the trouble began is now named Haley Falls (Tim Ernst made that happen), and Haley has climbed down that tree to see it many times since.

The scene of Steve and Kelly taking their daughter home to Fayetteville on the morning of Wednesday, May 2, 2001, is a TV cliché you can well imagine: crowd of reporters on the lawn, news vans jamming the ordinarily quiet suburban street. Mailbox overflowing with cards and letters from well-wishers, many from people the family knew and many not, including one from Robin Williams, who had been following the story. Haley said no to appearing on Oprah because she didn’t know who Oprah was. It’s a testament to Steve and Kelly’s judgment that this decision was apparently Haley’s call. They did say yes to some media coverage—including that episode of Dateline NBC—but they wanted more than anything to get back to their ordinary lives.

They thought it best to leave town for a bit, and they asked Haley where she wanted to go. Her favorite thing she had ever seen in her short life was the Gateway Arch, which they’d visited on a family vacation, so they decided to take a short trip to St. Louis. During the drive up, Haley told them for the first time—told anyone for the first time—about her “imaginary friend,” Alecia.

From the moment Alecia first appeared in the story, Haley insisted on that slightly unorthodox spelling, although she did not yet perfectly know how to read. She also insisted on other specific details. Alecia was four years old. She had long, dark hair tied in pigtails. She wore a red shirt with purple sleeves, bell-bottom pants, and white sneakers. She had a flashlight. She guided Haley to the river.

“I never had imaginary friends before this experience,” Haley told me, “and I never had any after. And I never saw this particular imaginary friend again.” She did not think at any time that Alecia was a real child. “I was fully aware that this was a non-corporeal being that was with me. And she was a little girl, and we had conversations, we told stories, we played patty-cake, and she was just a very comforting presence. But I knew I was alone.” The hallucinations started later, after she’d already made it to the river. Alecia was not a vision of this sort. “I one hundred percent did not think there was another child with me. I knew, physically, I was alone.” But she also says that Alecia guided her to the river, which she didn’t know was there.

There is a phenomenon called third man syndrome, or third man factor: when some sort of unseen or incorporeal conscious presence seems to accompany people—often a person alone—going through a long, difficult, and frightening experience they do not know they will survive. It is not well understood. It may be some sort of emergency coping mechanism. It was most famously experienced by Sir Ernest Shackleton during one of his expeditions to the Antarctic; the mountaineer Reinhold Messner has also reported experiencing the phenomenon, as have the explorers Peter Hillary and Ann Bancroft. “During that long and racking march of thirty-six hours over the unnamed mountains and glaciers of South Georgia,” Shackleton wrote in his 1919 memoir, South, “it seemed to me often that we were four, not three.” T. S. Eliot read that book, and with characteristic pedantry tells us in his own commentary on The Waste Land that it inspired these lines:

Who is the third who walks always beside you?

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

I do not know whether a man or a woman.

—But who is that on the other side of you?

Before moving on, I should tell you that my father’s family is not particularly religious. A few softcore Christmas-and-Easter Christians are the most pious among them. Although Jay and Joyce both grew up regularly attending church, per Joyce, “We both drifted away on our own in college and became uninterested in organized religion.” Steve and Kelly took Haley to Methodist services sometimes, but they were not really regular churchgoers either. Religion has just never been a big part of the lives of the people on that side of my family, and I’ve long thought of them as admirably sane, skeptical, rational thinkers.

Before reading Tim Ernst’s book about Haley’s rescue, I did not know that Kelly called a psychic from the landline in his cabin on the first night after Haley went missing. Here’s Tim:

Then Kelly got an idea to call a psychic and wanted to know if I had a phone book. She must have detected a slight hint of skepticism in my face because she looked right at me and said, “At this point I am willing to try anything!”

No atheists in foxholes. Tim continues:

At 11:08 pm she placed a call and spoke briefly with a psychic. . . . “She is lying down next to a stream and is unhurt,” the psychic said. . . . As it turns out, this information was exactly correct.

I disagree with Tim that what the psychic said could be called “information,” but it’s true she happened to be right. At that moment, Haley was lying on a rock in the middle of the Buffalo hoping the helicopters would spot her. Perhaps that psychic simply possessed the same thing Lytle James and William Jeff Villines had: intuition. As Villines told the Dateline reporter whom it apparently took mighty persuasion to get them to talk to on camera, “We got to thinking that, well, if anything’s lost, most all the time they’ll go down to the river.”

The next day, Crow Johnson (Crow is a folk singer and textile artist who favors flowy scarves and Navajo jewelry, a crunchy über-hippie in addition to being a dyed-in-the-wool Arkie, and of my family’s friends it is thoroughly unsurprising that she would be the one to have this idea) mentioned that a convention of dowsers, or “water witches” as they’re sometimes called in the Ozarks, was being held at the Crescent Hotel in Eureka Springs, and she faxed them topographical maps of the area, which they faxed back with their divined suggestions for where to search.

I distinctly remember first learning about water divination from Jay and Joyce when I was a kid, walking in the woods with them on their property in Pea Ridge. Although they were deeply mistrustful of organized religion, and of Christianity in particular, which comes out of the radio on about half the stations you can pick up in Northwest Arkansas (the other half are country stations; there is one NPR station for the liberals, which Jay usually had on in his machine shop), and though they did not exactly believe in water divination, they had a strange sort of respect for it, as they did a lot of the old Ozark folk wisdom. It’s as deep a part of the landscape’s human psychology as the folk songs. Plus, it works sometimes. Those instances are almost certainly just lucky accidents, the coincidences of confirmation bias that give magical thinking its power over our pattern-hungry minds. But you’d have to have the heart of a robot not to feel at least a little tingle in your spine when it does.

I think all the business with psychics and water witches all but vanished from Kelly’s mind as soon as Haley had been found alive and safe. Joyce, on the other hand, in a way had an even worse experience of the trauma than Kelly, in that she was not only terrified for Haley during those three days, but also devastated with guilt. And still is. A part of her soul never got out of the foxhole.

When Kelly stepped out of the car in the parking lot of Cave Mountain Church on the day Haley went missing, Joyce was there to meet her. The first thing Joyce said was, “Will you ever forgive me?” And Kelly said, “There’s nothing to forgive. I’m not angry at all.” She was afraid that Steve would be furious with her parents, but he was not angry, either. Everyone involved with this story told me the same thing: no one ever blamed Joyce, or was ever angry at her. Despite all this, Joyce could not forgive herself. By many accounts, Joyce remained rattled and uneasy for a long time after Haley was found. One friend used the phrase “emotionally brittle.” It is a ridiculous understatement to say that she could not stop thinking about it. And now there was a new element thrown in: in the aftermath of Haley’s rescue, her “imaginary friend” made the rounds among the grownups, making everyone’s hair stand on end.

On August 24, 2001, four months after the ordeal, Tim Ernst—now a firm friend of the family—sent Joyce an email:

Just a tiny bit of bizarre lore that we thought about last night. Pam and I were sitting around talking about Haley’s Alecia, and Pam asked me if any little girls had ever been lost or died in the wilderness near here. A huge chill ran down my spine. You may recall this too. It was twenty years ago when a little girl from Springfield of all places, was tortured, murdered, and stuffed in a pickle bucket and buried by a small group of cult members. The cult members were told to “go to the wilderness and exercise the demons” from this little girl. That location was just off of the Kapark road, which is about three or four miles from here as the crow flies. I have not decided yet if I am going to dig up the specifics of this case—wouldn’t it just be CRAZY if that little girl’s name was Alecia, or was anything like Haley’s Alecia!!! I have not told Kelly about this, and it probably is just meaningless anyway, but just the thought of the possibilities . . .

Tim knew the murder had happened about twenty years earlier, but did not know the exact date. Jay and Joyce had been living in Northwest Arkansas at the time but did not remember the story. A few days later, after doing some research, Tim wrote Joyce another email:

It turns out that this cult had just moved to the woods from Rogers, and had charges pending in Benton County, and were first taken to the jail there (I’m sure there was plenty of news coverage, although we still can’t find out what year it happened).

Joyce took it from there: She went to the Benton County Sheriff’s Department and asked whether they had any records having to do with this incident, or knew anything about it. They didn’t. But someone in the office did vaguely recall that Judge Tom Keith had somehow been involved with the case. And it just so happened that Jay and Joyce knew Tom Keith pretty well. Jay and Tom had served together as justices of the peace on the Benton County Quorum Court. Joyce called up Tom Keith. And yes, he had been involved with that case. Before he was a judge, Keith had worked as a public defender for Benton County, and he had been one of the two lawyers on the defense counsel of one of the cult members charged with the murder, the only defendant whose case went to trial: the murdered girl’s mother.

“When I called him,” Joyce wrote in an email,

I remember a long pause before he spoke. I was afraid that client privilege was still an issue and that he wouldn’t feel he could help. After a while, all he said was that I needed to research the newspapers for April, 1978. After that I should make an appointment with his secretary.

Joyce hit the microfiches at the local library and filled herself in on the broad outline of the story. Then, late that summer, she brought Kelly along, and met with Judge Keith in his office. Tom Keith told them that defending the mother of the murdered girl had not been just any job for him: he believed in her innocence, and he still believed that her conviction was a shameful and tragic miscarriage of justice. He considered losing that case the worst failure of his career, and it had haunted him ever since.

Early in the morning on Tuesday, April 25, 1978, Newton County game warden Fred Bell was out with a friend in the woods about a mile southeast of Cave Mountain Church and Kapark Cemetery on Cave Mountain Road, above the bluff on the east side of Cave Mountain that overlooks the Buffalo River valley, hunting turkeys. He was not on duty. While heading back to the road, they came across a campsite: a truck with a camper-trailer hitched to the tow, a couple of tents, and the remains of a firepit. It was an odd place to be camping: pretty far from the road, not on a trail, not very close to any water. They were six people, all white: a man in his fifties, a man and a woman in their early thirties, a woman in her early twenties, a teenage boy, and a girl of about nine. Fred talked with them for a while, and showed them his game warden’s badge. They did not appear to be doing anything illegal, but—according to Ray Watkins, who was a Newton County deputy sheriff at the time, has long since retired, and now works at Bob’s Do It Best Hardware and Lumber in Jasper—Fred thought they were “acting kinda funny.” Fred wrote down the license plate numbers and he and his friend hiked back to Cave Mountain Road, where they saw another car parked there that they didn’t recognize, which they correctly guessed was another vehicle belonging to the group, and he took its plate number too. They walked up the road to where Fred’s truck was parked—his official vehicle—and he radioed the sheriff’s office, got Ray, and read off the plate numbers. Ray ran them and got back to him a few minutes later: the vehicles were linked to several people who had an active warrant out for their arrest in Benton County on suspicion of child abuse. They also supposedly had another young child with them, a little girl probably not older than five.

Ray Watkins and three other officers met up at the house of Newton County sheriff Hershel Fowler, which happened to be three miles from Cave Mountain Road—it was still early in the morning and the sheriff hadn’t come to work yet—and then they all drove up to the top of the mountain to meet Fred Bell and his hunting buddy on the road. Fred and his friend led them to the campsite, and this is Ray’s memory of what happened next:

Well what happened was that these four people that were the mother of the child, Clark was I believe her name, and then the Harrises and this other lady were tied into bein a religious deal, I guess. The younger one, he was leadin them and tellin em what to do, and this Clark lady had a little girl, bout five I believe, and she was small for her age. . . . We found out that they were wanted for child abuse, and so we—three other guys, the sheriff and myself and the game warden and another guy—went in there and found em and asked em to step out of the trailer. And we got em out, and they was armed to the hilt, and the little girl was gone—she wasn’t there. And so while I was fixin to take em to jail the sheriff was checkin the area and he found a place that looked like somebody’d dug a hole and buried somethin, so he dug it up and he found that five–gallon bucket with her in it, the little girl. She had been shot about fifteen–sixteen times, and it was that religious deal, because the prophet had ordered her killed because she had the devil in her. So that’s what happened, we brought em out and took em to jail and they went to court and they entered pleas. I believe they got life, and some a little less. And the mother she—the prosecuting attorney gave her immunity because he was gonna have her testify. But we really didn’t need her, we had enough evidence to hang em all, but she got off, did the deal, and the other three went to penitentiary, and I don’t know what happened to em after they went down there. They were all charged except for that Clark lady, and the sheriff was pretty upset that the prosecutor gave her immunity, because she was just as guilty as they were—lettin em kill her daughter.

Later, Watkins added this:

I was the one that took em out of that camper-trailer. After the others had come out, the prophet, he was still settin in the trailer, he didn’t want to get out. And I finally told him, if he didn’t get out of there, I was gonna pull him out of there. I said there’s a warrant out for you. When I got him out of there, he was settin on a .44 Magnum. And if he had got his hands on that, it would’ve—I wouldn’t be here. I guarantee you. Not with his mindset. Havin that little girl killed—helpless.

Watkins was right to say they were “armed to the hilt.” This is from the Blytheville Courier News coverage of one of the court dates, from September 5, 1978:

Newton County Sheriff E.H. Fowler said in April authorities confiscated 15 to 20 weapons and “something like 2,000 rounds of ammunition” from a van belonging to the sect. The weapons included seven or eight rifles and pistols of assorted calibers, he said.

The van also contained food, clothing and several copies of a book entitled “The Third Step to Joyful Living, or How to Stop Worrying” by Royal and Edith Harris.

A few details of Ray’s account are not synoptic with other records of what happened—understandably, as it happened forty-five years ago—but in a telling way that has to do with another part of this story.

While the cult members were sitting in handcuffs in the cruisers, Hershel Fowler discovered the hastily buried remains of three-year-old Bethany Allana Clark. The coroner would estimate her time of death to be either late Sunday night or early Monday morning. The coroner also noted bruises and burn injuries. She had been shot eight times with a .22 and stuffed in a plastic mesh bag, which was stuffed in a five-gallon plastic bucket and buried about two feet deep, and then someone dragged a few logs over the spot. Ray describes the cult members they arrested as “four people that were the mother of the child . . . and then the Harrises and this other lady.” I think he misremembered them as four because there were four people who were charged for Bethany’s murder: Royal Harris, 50; his stepson, Winston Van Harris, 31; Mark Harris, 17; and Bethany’s mother, Lucy Clark, 22.2 But officers arrested five people that day: the fifth was Suzette Freeman, 31. It was Suzette Freeman, not Lucy Clark, whom the prosecutor offered immunity in exchange for testifying.

In 1972, Royal Harris—a World War II Air Force veteran—founded the Church of God in Christ Through the Holy Spirit, Inc. (it was a corporation, for tax purposes) in Florida with his wife (and co-author of the self-published book The Third Step to Joyful Living, or How to Stop Worrying, which is listed in the Library of Congress), Edith, who had been a Methodist minister. (I had expected to find they had been connected to some crazy spandrel of Christianity involving snake handling or speaking in tongues; but no, that this cult apparently grew out of Methodism, which I think of as the vanilla ice cream of Protestant denominations, is one of this story’s many bizarre details.) Winston Van Harris was Edith’s son from a previous relationship, and Mark Harris was Royal and Edith’s son, whom his mother—who seems to have been the real founder and main driving force behind the cult before she died—had declared to be a prophet. Winston—called Van—was married to a woman named June who also joined the cult, and they had a young son named Matthew David. Larry and Suzette Freeman became early members of the cult, and Suzette seems to have grown to occupy a central role in its power structure (at its largest, the cult consisted of nine adults and several children): she was “the Interpreter,” believed to have the power to act as a sort of intermediary for the mystical pronouncements of the teenage Mark Harris, believed in turn to have direct access to God. At some point in the mid-Seventies the group moved from Florida to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which is where Lucy Clark met them.

Lucy Clark was born in Baton Rouge in 1956 and grew up near there on her family’s farm in Walker, Louisiana. At eighteen she married her high school sweetheart, Allen Clark, who soon began beating and otherwise abusing her. “I was not allowed to see my family even though they only lived three miles from me,” Lucy recalled. “Many times my Dad would come by my house and I would pretend I was not at home because I did not want him to see my face black and blue and eyes swollen shut. I was not raised in a family that was abusive like that. At that time, I was pregnant with Bethany.” Allen left Lucy for another woman when Bethany was a few months old. “So here I was a child with a child devastated and just didn’t know where to go.”

A few months later, in 1976, Lucy went to the employment agency in Baton Rouge where Suzette Freeman and June Harris worked. Abused, heartbroken, taking care of her infant daughter, nineteen years old and desperate for money, she was in a dangerously vulnerable and emotionally fragile state—i.e., she fit the profile of exactly the sort of person cults prey upon. (An employment agency is a good place to meet desperate people.) “They sent me on a couple of interviews,” Lucy told me recently, “and I think I got a job. I can’t even remember where the hell it was at now. But then they would start wanting to know how I was doing, because they knew the relationship I was in, and they knew that I had a baby—and they kind of drew me in, and I went to Suzette’s house, and they were talking about their church and I. . . . At the time I was so beaten down by my husband and then you have this little light. That’s how they kind of put me in there. How I got involved with them. . . . I was young, stupid, and in a beating relationship, and just so far down that I didn’t even hardly know my own damn name. And so it was like, they just kind of sucked me in.”

Lucy became more and more involved with the cult over the next two years, growing isolated from her friends and family: “It was days that I sat in the chair and it was like that toward right before we left, ‘Your parents don’t love you and they’re bad for you and you can’t talk to them, and you can’t go around them and you can’t see them.’ ” After these two years in Louisiana, “all of a sudden we were supposed to be going to Arkansas, because of such and such tribulation and this kind of stuff. All the bad stuff didn’t happen until we got to Arkansas.”

The Church of Christ in God through the Holy Spirit, Inc. moved from the Baton Rouge area to Northwest Arkansas. They bought a trailer and rented another next to it in the Midway Trailer Park in Springdale, and rented an apartment not far away in Rogers. For a time, Royal and Mark were living in one trailer, Winston Van and June lived with their young son in the other, Lucy and Bethany slept in a small camper-trailer parked in the driveway, and everyone else—the Freemans and Johnny Stablier—lived in the apartment in Rogers. At some point, Suzette ordered Lucy and Bethany to move in with them in the apartment.

The chronology leading up to Bethany Allana Clark’s murder in the Buffalo National River Wilderness is muddy and confusing, but there was definitely a period of time in which Lucy was working three different jobs—she worked at a Tyson poultry plant, a Long John Silver’s, and a café—and turning all her earnings over to the cult. (Winton Van Harris also worked at the Tyson plant; none of the other members worked.) Bethany Allana was often left in the care of the others. Initially, Lucy drove herself to and from her various jobs, but eventually someone else in the cult began to escort her. “I was scared of these people,” Lucy told me. “You couldn’t go nowhere. You couldn’t call your family. My family did not know where I was at. And I had wrote letters. Even after all this happened, I know I told my sister, I wrote you letters. And she said, I never got them. So I wrote the letters, but they wouldn’t send them. They would destroy them. They took all my stuff. I come home from work one day and Suzette had sold my wedding rings and my graduation ring.” Her clothes also went missing.

Some of the more horrific anecdotes about things that happened during this time surfaced in Lucy’s trial, and are mentioned in the newspaper coverage of it—for example this, from the September 13, 1978, Blytheville Courier News, describing June Harris’s testimony:

Mrs. Harris said sometime in late March, a meeting was called concerning [Bethany].

At that meeting, Mark Harris placed a pot on the coffee table in one of the members’ homes in Rogers and started a fire in it. He ordered Mrs. [Clark] to get some pictures and [Bethany’s] doll and threw them into the fire, she said.

Mrs. [Clark] tore the clothes off the doll and threw them and pieces of the pictures into the fire, Mrs. Harris testified.

When flames shot up out of the pot, Mrs. Harris recalled that Mrs. Freeman said, “That’s what it’s going to be like, [Bethany], in hell.”

She then screamed to [Bethany], “Put your hand in the fire,” Mrs. Harris testified.

She said Winston Van Harris took the child’s hand and placed it into the flames. Mrs. [Clark] did not try to stop them; she only called out, “Van,” Mrs. Harris testified.

Mrs. Freeman then held [Bethany] over the fire, Mrs. Harris recalled. She said that afterward [Bethany’s] hand was black and blistered.

The hand was placed in ice water, then wrapped in gauze, but no other medical attention was given, she testified.

Lucy says a lot of what Suzette and June said is not true; but the coroner confirmed there was evidence of burn injuries on Bethany’s hand and other parts of her body.

Everyone seemed to live in terror of Mark Harris and Suzette Freeman—the Prophet and the Interpreter. The founding member of the cult, Royal Harris, appears to have taken on a secondary role: his job was not to make decisions, but to enforce Mark and Suzette’s rule. At one point in one of the court transcripts, Richard Parker, the public defender appointed to Mark Harris, arguing for a lighter sentence for his client, says, “We would ask you to consider that if a seventeen-year-old boy orders or tells his father and his brother who is almost twice his age to go out and shoot a child, and they actually go do it, who should owe the greater responsibility or draw the greater penalty, the boy for telling them to do so, or the father and the brother for actually going out and doing it?” It is disturbing to imagine how Mark Harris acquired this seemingly absolute—divine—power over the others; his mother, Edith, declared that her son would be a prophet in 1972, when he was thirteen years old, and died not long afterward. The boy seems to have been in control of everyone else, including his father, since then. The lion shall lie down with the lamb, and a little child will lead them. “At that time, my fear of those people and God was so great it was as like I was nobody,” Lucy recalled. “I honestly believed that they were getting these messages and if I did anything, they would know about it because God would tell them. I was doomed any way I went.”

The sequence of events that led to their arrest in the woods began sometime in mid-April, when the cult declared June Harris—Winston Van Harris’s wife, who might have been in the cult even longer than Suzette had—anathema, accused her of having an affair with a woman who lived nearby, and of worshipping the devil, and cast her out of the church, while keeping her son, Matthew David, who may have been suffering from routine physical abuse on Mark and Suzette’s orders, as Bethany had. Her husband gave her some money and let her take their car. Distraught and panicked, June drove all night to Baton Rouge, but when she got there she had second thoughts, turned around, and drove all the way back to Rogers to try to get her son back. (That’s about a ten-hour drive each way.) She met with a family law attorney in Rogers and explained at least some part of the situation to him.

The lawyer’s name got lost in the shuffle, and it’s not clear what exactly happened after that, but basically, his reaction to June’s story was: This is not a hire-a-lawyer problem you have, this is a call-the-cops problem. The lawyer called the police and told them he was almost certain that something dark and crazy and deeply fucked-up and involving young children was happening in that trailer park—and that there was a woman who needed to get her son out of there right now. Before they had the arrest warrant, cops escorted June Harris to the Springdale trailer park, where they took Matthew David and returned him to June. Lucy and Bethany were inside the trailer. “And they would not let me go outside because I would’ve left them,” Lucy told me. “I said, ‘Just let me go home, just let me go home. . . .’ But when the cops came to get Matthew, they refused to let me go out of the room. And the cops never came in the trailer. So it was like, Oh my God, that was my chance.”

When the police retrieved Matthew David from Royal’s trailer, they also wrote down the license plate numbers of the cars parked outside. The cult’s bubble had burst: the outside world was paying attention to them for the first time. Benton County issued a warrant for their arrest for suspected child abuse. By the time the police returned to Midway Trailer Park later that day to arrest them, they had fled, and one of the trailers was on fire. That night, the cult sent Lucy and her daughter to a hotel somewhere outside Fayetteville under an alias, while, according to Lucy, “they got all their stuff together, I guess with the guns and the trailer, the U-Haul and all that stuff.”

Lucy knows now this night alone with her daughter was another lost opportunity to escape: “I’ve had many people ask me, Why didn’t you leave, why didn’t you leave? I don’t know why. I didn’t leave ’cause I was scared. ’Cause they watched me all the time.” And the next day, “they come got me.” Then Royal, Van, Mark, Suzette, Suzette’s daughter Desha (whom Ray Watkins did not remember), Lucy, and Bethany, in several different vehicles including a rented U-Haul, drove to the Buffalo National River Wilderness and bivouacked in the woods south of Cave Mountain Church. Meanwhile, Suzette’s husband, Larry Freeman, and Johnny Stablier drove—also on Mark and Suzette’s orders—up to Columbia, Missouri, where Larry’s ex-wife lived with their two children, to kidnap the children and bring them to the place where the others were camped in order to await what they called “the Tribulation.” Mark had prophesied, and Suzette had confirmed through interpretation, a period of apocalyptic chaos, which would commence with a nuclear war and end with the second coming of Christ. Larry Freeman and Johnny Stablier tied up Larry’s ex-wife and kidnapped the two kids, but were arrested on the road an hour later.

While the others were camping, Mark Harris declared, and Suzette verified, that Bethany Allana Clark was anathema and had to die. We know this because Mark said as much in court during his sentencing. One particularly disturbing thing about the court transcripts is that Royal and Winston Van Harris seem aware that the jig is definitely up—they understand they’re about to be sentenced for murder, and are no longer in make-believe land—whereas Mark Harris does not. He is still the Prophet. He goes off on irrelevant flights of quasi-Christian mystical gobbledygook that the judge frequently interrupts with things like, “Mr. Harris, at this time I do not want to get into the philosophy of the church.” Mark is still, so to speak, drinking the Kool-Aid—his own. (Of course, that wasn’t a popular idiom yet; the Jonestown massacre would happen a little less than two months after the end of Lucy’s trial.)

That is the why of the murder. The how of it is a matter of some dispute. “Each one of em had shot her,” Ray Watkins said. “That’s what the Prophet wanted to do, have each one of em shoot that little girl. That’s what the others told me.” But the narrative solidified into this: On Monday morning, Royal Harris and Winston Van Harris took Bethany Allana out of sight about fifty feet away from the campsite, and about an hour later came back without her. Lucy maintains that she never heard the gunshots. Though they were not very far away, this isn’t implausible—we have already discussed how sound does not travel very far in the Buffalo National River Wilderness in late April, with full foliage on the trees (the area where they were camped was exactly the place where Haley would be when she first got lost, before she climbed down the bluff—much closer than Tim Ernst initially remembered). Plus, a .22 is a small-bore weapon that doesn’t make much noise. That may have even been precisely why they used it—as Ray Watkins duly noted, they had plenty more powerful firearms with them. It may have also been the reason it took eight shots to kill her. (When I was a kid learning to shoot with Jay and my dad, they started me with a .22 rifle—a “pea shooter”—because a kid can fire it fairly safely—very little recoil. I remember, picking up the Coke cans I’d just shot off a log, that the bullets were still rattling around inside them: it was powerful enough to blow through one side but not the other; the aluminum cans had no “exit wounds.”) In court, Royal insisted he was the only one who pulled the trigger—eight times—but that may have been a story they’d agreed upon in hopes that the much older man would get the longer prison sentence rather than his thirty-one-year-old stepson or his seventeen-year-old son.

Forty-five years later, Lucy’s memory may be muddled, and when we spoke she contradicted what she had said in court about not hearing the gunshots. She told me that she and Bethany spent the first night in the woods in a tent with Suzette and Desha, and the next morning “Suzette said Van and Royal were going to get some water and they wanted Bethany to go with them. . . . He took her by the hand and said, ‘We’ll be right back.’ And then I’m sittin on this log, and that’s when I heard the shots. . . . They came back, they didn’t have her. And I wanted to know where they were, and Suzette kept telling me, ‘You sit down and hush, just sit down and hush. It’s okay. It’s okay.’ ” Lucy does not remember what happened that night, but the next morning Fred Bell and his friend showed up, and then came the arrests; she does remember that they were all holed up in the camper-trailer when the police got there, and that Van had a .357 Magnum. “They knocked on the door and Van said, ‘Shut up, don’t say nothing.’ And they opened the door and they went outside. And that’s when all they got us.” Lucy told me that if the sheriffs hadn’t arrested them all when they did, she was sure “they would’ve killed me, too.”

Initially, all pleaded not guilty, but in the coming months, Royal, Mark, and Winston Van Harris switched their pleas to nolo contendere, nolo contendere, and guilty, respectively, while Lucy Clark maintained her plea of not guilty—thus hers was the only case that went to trial. Suzette Freeman was offered immunity in exchange for testifying against Lucy. Ray Watkins misremembered it being Lucy who was offered immunity rather than Suzette, but I do believe him that the sheriff was pissed off at the prosecuting attorney for offering any of them immunity, because he thought they were all equally guilty and furthermore they didn’t need the additional evidence to convict.

Why Suzette was allowed to walk and Lucy was put on trial is unclear, but it’s tempting to put it down to the very facts that make it seem, in retrospect, like the opposite outcome might have been more just: Suzette was much older and more experienced, and by most accounts a terrifyingly forceful and manipulative person; Lucy, on the other hand, was a twenty-two-year-old single mother, a woman who had been badly abused and then abandoned by her husband before she joined a cult, a person who had been terrified of disobeying Mark and Suzette because she seriously believed that if she did God would tell them. That is to say, Suzette was probably a lot better than Lucy at talking people into things.

At any rate, when it was all over, Royal and Mark Harris (the latter of whom had turned eighteen in jail awaiting sentencing) were both given life in prison. Winston Van Harris was given fifty years plus another fifteen for illegal possession of a firearm. Lucy Clark was found guilty and sentenced to five years; she was released after two. Royal Harris died in prison in 1998. Winston Van Harris was released in 2003. Mark Harris was released in 2009. Both were model inmates, and were transferred to low-security prisons decades ago. Suzette Harris served no time, and she died in Baton Rouge in 2019 at the age of seventy-two.

After her release, Lucy Clark moved back to the family farm near Baton Rouge, where she remarried and had another daughter, who grew up and had her own children. She still lives on that farm today. A few of the people closest to her—like her husband—know about her past, but most within her general social orbit do not. In April 2004, Lucy received an email from my Aunt Joyce.

Sitting in his office in Benton County at the end of August 2001, Judge Tom Keith told Joyce and Kelly of his deep and painful regrets about Lucy’s case. He thought she was innocent, and never should have served any prison time. Keith had first been assigned to Lucy’s defense when she and the others were taken to Benton County (where the warrant for their arrest had been issued); she established an early rapport with him there, and she had to write a letter to the judge presiding over her trial for murder in Newton County to allow him to continue representing her. “He was my rock,” Lucy now says of Keith.

Lucy had been brutally abused, brainwashed, and terrorized by the Harrises and Suzette before they murdered her daughter, and after a short life that had been nothing but brutal abuse and terror for four years—first at the hands of her husband, and then by the cult—furthermore had to endure the humiliating ordeal of the trial and the local press’s callous and often incorrect sensationalizing of it. “Everyone has his ‘own’ idea about my case which was sensationalized by the newspapers and TV media,” Lucy wrote in an email to Joyce. “They know nothing of the horror, nothing. I never knew who killed my daughter until the trial was almost over.” The years of terror and abuse continued while Lucy was in jail. She was the only woman being held in Benton County Jail, and she told me that one of the deputies unlocked her cell and let in one of the male inmates, who “basically raped” her: “The deputy let him in there in my cell one morning. I know the deputy got fired, but hey, you didn’t hear about that in the paper, did you? Nope.”

That summer, an inmate started a fire in the jail in an attempt at escape, and while it was being extinguished and the damage repaired, Lucy was kept in a cell with all the male inmates. “These guys pissed on me and they spit at me,” she says, “and there was piss all over the floor and they just left me there all day.” And she recalls the humiliation she was subjected to in the Boone County Jail lavatories: “At the end of the hallway was the shower, which had no curtain on it. And I would ask [the sheriff’s officer] for a shower and he would stand at that door and watch me while I took a shower with just a washcloth.”

Lucy Clark suffered all this while one of the ringleaders of the cult walked free in exchange for testifying against her. “Suzette was whiz at this stuff,” Lucy says. “The very person who gave them the order to kill that baby and to kill me was the one who got immunity and got off scot-free.”

Tom Keith believed that if all this had happened after the Jonestown massacre—which did more than any other event to change the public’s understanding of cult psychology—the jury and the press might have better understood the power of brainwashing and the impossibly weak position Lucy was in, and would have had more sympathy. Of course that’s possible—but as we’ve seen recently with a tabloid fixation from a few years ago, Casey Anthony, there is absolutely nothing that incites the rabble to misogynistic wrath more than the story of a mother who somehow causes or permits the death of her own child. It scratches at some instinctual horror lodged deep in our mammalian middle-brain. There is something about it people find so horrible that they perversely want it to be true. It’s the nightmare on the other side of what Colleen Nick told Kelly, advising her to emote like hell for the cameras: “There is nothing stronger and more understood by people than a bond between a mother and child.”

Tom Keith remained outraged and bitter about Lucy’s conviction and subsequent prison sentence until the day he died, but when I spoke with Lucy I found her attitude about it contemplative and penitent. She is still angry about Suzette being given immunity, but she seems at peace with her own conviction.

Lucy was convicted of murder in September 1978. The day after the trial ended, the foreman of the jury, a woman named Catherine Nance, visited her in Boone County Jail. Lucy: “She wasn’t mean, she was nice. She was compassionate. But she said, ‘We didn’t find you guilty of murder. We found you guilty because you couldn’t tell the future.’ . . . I should have known what they were doing. I should have foretold, should have seen better than what I did. . . . And she brought me some books. I kept those books for a long time. And then one day I just threw them all away.”

Lucy spent two years in a women’s correctional facility in Pine Bluff, a place she speaks of in a tone almost of serenity and gratitude. Her time in prison was the first time in more than five years—her husband, the cult, the jail—that she had been in a relatively safe place. “You would think it’s a college campus,” she said about arriving at the women’s prison. “There’s no bars, there’s all glass. Everybody wore their clothes. So it wasn’t like one of these dark places you see on TV with the bars and all that. It was none of that. And I got an education. I had graduated from high school but I did another course there, it was a two-year course. I finished it in a year. So that place wasn’t all bad. You had bad people there, but basically it was okay. It looked basically like a college dorm. The only thing is that they lock you in at night.”

After meeting with Joyce and Kelly in late August, Judge Keith—who had stayed in touch with Lucy ever since the trial—wrote to ask if she minded him giving her email to Joyce; Keith was one of the very few people Lucy trusted, and Keith told her she could trust Joyce. It took her a while to decide, but eventually Lucy said yes. Joyce emailed Lucy. Lucy emailed her back. And thus began an extremely unlikely long-distance friendship between the two women.

Their friendship was built on the apparent connections between Haley’s disappearance and Bethany Allana’s murder—and between them, Alecia. Several astounding coincidences line up, starting with the fact that the two incidents both happened in late April, and they happened (or in Haley’s case, began) in damn near exactly the same place. A lot of things happen in a lot of same places, but that particular place happens to be an extraordinarily remote, very sparsely populated area. As Ray Watkins put it, “A wilderness area really, there ain’t nothin in there.” Then there was the fact that Haley said her imaginary friend had dark hair she wore in pigtails, as Bethany Allana had and often did, and that she was four years old (Bethany Allana was almost four when she was killed). As Joyce and Lucy emailed back and forth about it, other connections inevitably surfaced: Haley said Alecia had a flashlight with her—which would have been useful in those dark woods if Haley had actually had one; Lucy and Bethany Allana liked to pass the time playing patty-cake, which Alecia did with Haley; one time, Lucy says, Suzette took away one of Bethany Allana’s only cherished and comforting possessions, a Raggedy Ann doll (possibly the same doll June Harris mentioned in her testimony) because it was demonic idolatry or something, and the best thing Lucy could replace it with was a flashlight, which the child thereafter always held on to and clutched under the covers in bed at night as she had done her doll: “[Suzette] would just turn the lights off,” Lucy says, “and I had to give Bethany a flashlight. So she wouldn’t be so scared.” There were other felicitous connections like that, but in my opinion everything that travels further afield from objective recorded facts—such as the time and place where these events happened—feels more and more to me like people finding new breadcrumbs leading to an answer they’ve already decided upon.

I, myself, am a skeptic—in this, and in most things. I do not believe—as Lucy believes, and as I think Joyce sort-of-maybe-kind-of believes—that Haley’s imaginary friend was the ghost or spirit or something of Bethany Allana Clark come to comfort and guide Haley when she was lost. (For one thing, “guide”? Guide her where? Really far away from almost all of the hundreds of people who were out looking for her?) Haley does not believe this either. As Haley with admirable wisdom and maturity said to me, “There are things that I will never know, and that’s okay.” But one of the emails Lucy wrote to Joyce contains something that gives even me the willies:

Bethany’s middle name is Allana. Sometimes she would say her name is Alasee (al a see). I would tell her no it’s Allana. She would laugh. I would think how funny she even came up with that name as it was a little different than her own.

Imagine a toddler with a Southern accent saying the words “all I see,” giving the last word a slight extra half-syllable, a diphthong it’s called in linguistics. Stretched out phonetically: all ah see-ah.

One of the things Joyce and Lucy have in common is that they are both people who every day for many years—probably still, for both of them—felt eaten alive with guilt. One thing I know I believe is that neither of them should be: Lucy was an abused, conditioned, and brainwashed cult member earnestly awaiting the end of the world, and Joyce did something that absolutely anyone could have done. But I also know it’s impossible for them not to be. Joyce’s whole quest to contact Lucy, and her correspondence with her, may in an indirect way be a product of that guilt. And likewise, Lucy needs to believe that Bethany Allana’s spirit comforted and guided Haley through her days and nights lost alone in the wilderness because it gives her some small “peace of mind,” as Joyce put it. “She had come to the idea that Bethany had actually had a meaningful life if she had existed in some form to help Haley.” As Lucy wrote to Joyce in one of her emails: “To know she saved someone else is beyond happiness and I am so thankful she was there for Haley. Being in the Buffalo Wilderness myself, there was no way Haley could have survived her ordeal alone. I suppose one aspect of all this is that Bethany was destined to die to save Haley and Haley had to live to save me in some sort of way.” And Lucy told me: “I don’t believe in psychics, I don’t believe in mediums, ’cause that’s not of God, that’s not God at all. People like to rely on things like that, but this was an angel that was sent. And maybe it was for me to heal,” she continued. “I don’t know, maybe it was for the both of us. I’m not sure. But it helps to know that her life, it didn’t end in vain, that she was able to help somebody else, and to help me, too.” She said she believes that “Bethany’s alive today, she’s in heaven, and that’s good.”