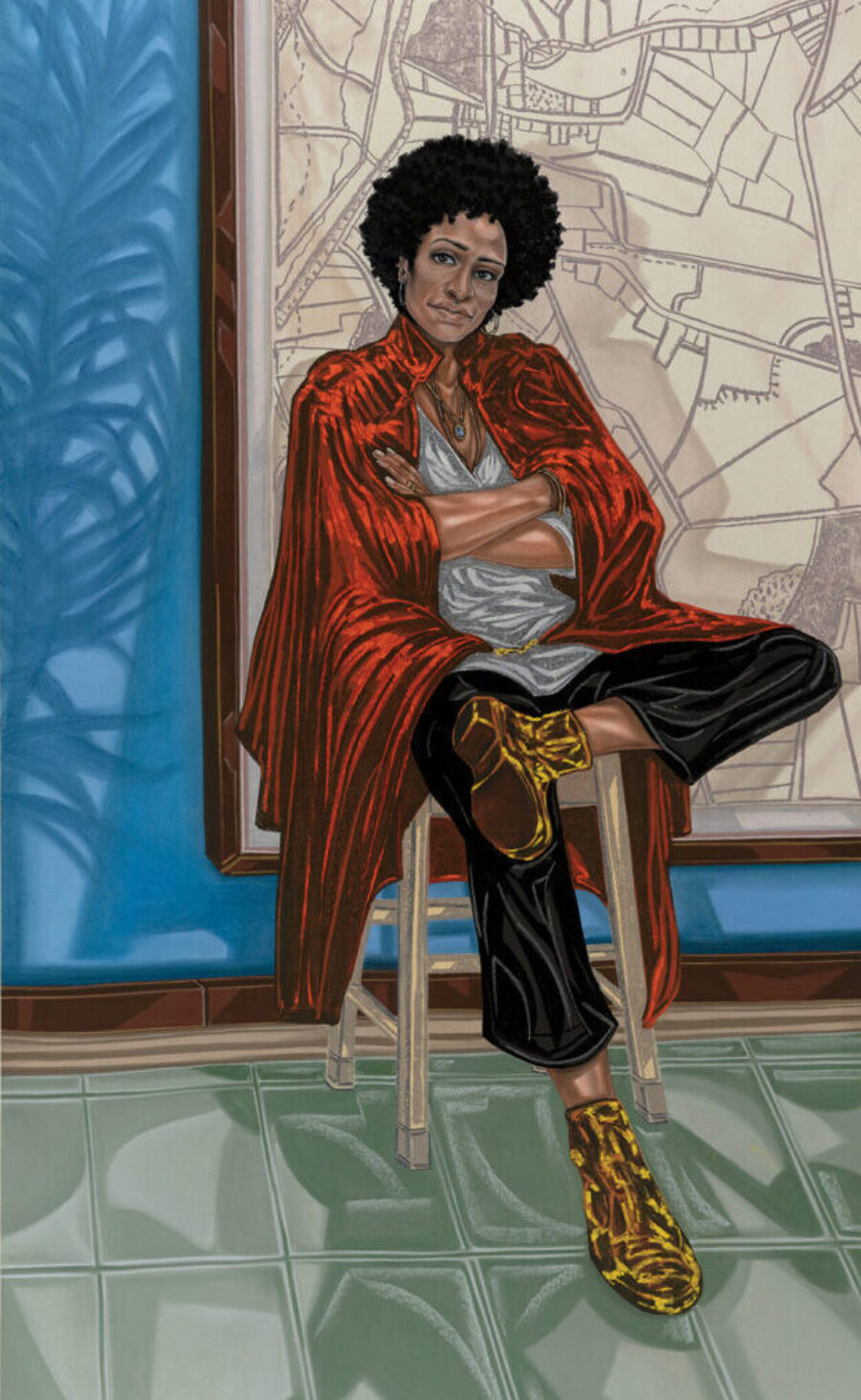

Sadie, 2018–19, by Toyin Ojih Odutola © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City

In Elif Batuman’s 2022 novel Either/Or, the narrator, Selin, goes to her college library to look for Prozac Nation, the 1994 memoir by Elizabeth Wurtzel. Both of Harvard’s copies are checked out, so instead she reads reviews of the book, including Michiko Kakutani’s in the New York Times, which Batuman quotes:

“Ms. Wurtzel’s self-important whining” made Ms. Kakutani “want to shake the author, and remind her that there are far worse fates than growing up during the 70’s in New York and going to Harvard.”

It’s a typically canny moment in a novel that strives…