Illustrations by Lorenzo Conti

The atelier was located in what had once been a small castle. Over centuries, the outer walls had fallen and the main hall had softened into a stone residence flanked by two low barns and bordered by narrow, grassy moats, dug long ago to keep a handful of people safe against marauders seeking—what?, Jacob Jiang wondered on the day of his arrival. It was a drab afternoon in early April 2007. The high fields on either side of the road were splintered with old stalks and stems, the reddish soil lay pale in the severe light. Who would want this place? What treasure had been sought?

Jacob approached the complex carrying his easel and a heavy suitcase. A man peered out from beneath an archway of withered vines. Jacob knew from photographs the goblin face, the aureole of whitening hair. Thomas Gaugnot’s hand was dry and thin, his handshake brief. He led Jacob across a courtyard and into the front room of the stone residence, where the painters lived. It was a cramped, dark room that smelled of burnt chestnuts. The massive fireplace was blackened to the ceiling, as if time itself had once turned there on an enormous spit.

“You have traveled a long way,” Gaugnot said, gesturing toward a chair. “The reason, you say, is to learn from me.”

Jacob struggled to unravel the man’s thick accent.

“You say, to learn to paint in what you call ‘a naturalistic style,’?” Gaugnot continued. “For this, you left New York. And yet I sense that you have, what do they say, a hidden motive, another reason for coming to my atelier.”

Jacob shifted in the too-small wooden chair. He felt within himself a clear, sustaining pilot flame of dislike. Gaugnot must be accustomed to receiving Americans of Jacob’s age—youngish but no longer young, casting away scraped-up savings to escape from a first set of bad choices. He forced himself to meet the unanticipated clarity of Gaugnot’s blue eyes.

“What do you mean?”

“They say my technique is obsolete,” Gaugnot said. “That is true. It is secret. It became a secret because no one cared. The attention of the world turned away from this kind of painting, what you call naturalism. You—” His gaze pushed Jacob back; the chair creaked. “You are here to learn the techniques of this secret.” He smiled a small, triumphant smile. “You think it is romantic.”

Three of the front barn’s walls were built of stone. High along the north wall, a rectangular window let a muted but entirely consistent light fall over the dozen students at their easels. Jacob let his pupils adjust, feeling soothed and stimulated by this light. He set up his easel in the only empty space. It was, of course, in a spot he did not like, at the least favorable angle to the seated model. He searched his pockets for a dime to tighten a screw that had undone itself with travel—no European coins were thin enough—and set up his paints slowly, taking pleasure in the moment of anticipation.

At last, holding a pencil, he turned to examine the model.

Even in the sunless room, her hair came alive. It was a dark mass of waves and curlicues, untethered to gravity. In shape and in value, impossible to paint. He resented Gaugnot for presenting the challenge. He heard suddenly, as if from a warped nursery record on an old turntable, the crabbed voice of the wizened dwarf: If you can spin this straw into gold, I will let you have your child. Looking below the dark cloud of hair, he found the lovely face, as delicate and as gentle as the medieval Italian master’s sepia sketch. The downcast gaze arrested at a point on the floor before his easel. The mouth tender and resigned, lips closed, but only just. Below the face, the body, flagrant in its sensual appeal. It was supple, brown, naked. Again, in its own way, impossible to paint; and yet it would be least discouraging to start with the body.

Jacob raised his pencil. His mother had taught him to draw in early childhood, without realizing how he would be gripped by the practice. He had picked up her habit of working quickly, making rapid impressions, usually good ones; but there was something in this space, in the seriousness of the other students, that seemed to demand a different approach.

He looked more closely. The hip swelled out in a tulip curve, closing in at the bent knee as cleanly as a tulip bud; but it was difficult to put to paper. Perhaps it was the north light that made her line so perfectly smooth. His pencil wavered. Just one stroke, one curve. Slowly. But the line was too hard. He erased it, leaving a mark, and glanced back at the model. Nothing had changed; her eyes remained on the floor, allowing him to look. He stood, his pencil at his side, looking. The room grew warmer. Doves cooed and fluttered under the eaves. The creaking door opened and closed as students left to use the bathroom or to smoke, then returned to their easels.

Gradually, Jacob became aware of Thomas Gaugnot behind him. Gaugnot’s breath smelled of sour coffee and an almost imperceptible decay. Jacob imagined the breath away, but Gaugnot did not leave. Now he hovered at Jacob’s shoulder—in his peripheral vision, Jacob could just glimpse a tuft of white hair. He began to sweat. Presumably, Gaugnot was sensing, in the remnants of his erased line, the truth: that Jacob was a talented draftsman who had never tried particularly hard, that he did not actually know how to draw.

He heard a rustle as if a wind had passed through the room. The others put down their charcoal and their brushes. It was time for a break. But he could not stop looking at the model. It was a numb stare of failure; and yet there was something he felt he might see if he tried hard enough. He did not turn away from the model and the model did not move. It was as if she knew he needed her to stay where she was.

Then Gaugnot stood next to her, touching the small of her back. “Hannah,” he said, and Jacob understood.

Gaugnot draped a white robe over her shoulders. Together he and Hannah walked to the corner, where most of the other students were already pouring hot water into cups.

Only Beth, Jacob’s neighbor, remained behind, straightening her brushes. She was a shy woman with sandy hair cut short, exposing her small ears.

“She likes you.”

There was a beat before he realized that Beth had spoken, for she had put into words a thought that had been in the back of his own mind.

“I’m behind. She waited because she can see that I’m new and I’m behind.” He was behind; he had been summoned as an alternate. Almost everyone had finished their first figure drawings, and they were now going over the charcoal with turpentine and brush. This slow technique had fallen out of favor a hundred and fifty years ago, as fashion turned to the more free-flowing process of impressionism. Somehow the practice had survived, passed on from painter to pupil. Still Jacob could not resist adding, “How would you know?”

Beth kept her gaze trained on the model’s empty chair. “I know.”

“Hope you’re right.” He caught her eye, risked a crooked grin.

“If I were you,” she said, “I wouldn’t even think about Hannah, unless I were drawing or painting her.”

On Jacob’s second full day, Gaugnot brought the class on a walk “to see the light.” It was a clear, warm day: the sun had regained dominion over the countryside after a long winter.

They came to an old stone windmill whose blades had been removed, a mute and flightless monolith. At its base, a wooden door opened into a chill, black space smelling of mildew. They followed the watery orb of Gaugnot’s flashlight up a flight of circular stairs: once around, twice around, the orb bobbed faintly on the rough inner wall. At last, they heard the scrape of a latch, the creak of heavy shutters. A narrow, brilliant shaft of sunlight pierced the darkness.

“Come here. Your turn. Stand at the window.” Gaugnot spoke to the student closest to him. There was a long silence. Jacob heard a few muttered words. Then, feeling his way, the student stepped carefully back down the stairs, past Jacob, out the door. “Come here,” Gaugnot said to someone else. “Your turn.”

One by one, they took turns at the window. Jacob could hear Gaugnot speaking what sounded like the same words to each. Impatiently, he wondered at the purpose of this field trip.

At last, Gaugnot said to him, “Come here.”

Jacob stepped up to the window, eyes shut against the dazzling sun.

“Open your eyes,” Gaugnot said, over his shoulder. “So you could see this light, I brought you here.”

Stubbornly, Jacob looked away, waited for his pupils to adjust, then at last returned his gaze out the window.

From a glowing field of wheat, a flock of blackbirds rose into the lucent sky. But they were strange blackbirds with white patches on their wings. Silent and disorienting in a sunny ditch stood something like a great blue heron, only smaller. From further up the road there came the sound of buzzing insects. He bent his head out of the narrow window to look more closely. The vibrations came from what appeared to be a pile of melting leaves in the middle of the road. It was the carcass of a small animal of some kind. Jacob held his gaze as the carcass swayed and moved, flapping with what looked like red-black butterflies.

The vivid colors and shapes appeared familiar, but entirely strange under the light. It was as if he had traveled into another point in history.

“Well, Jacob,” said a dry voice at his shoulder. “What do you see?”

He wondered if the question were a kind of test. He struggled for an answer.

“What do you see?”

He swallowed. “It’s—mysterious.”

Gaugnot said nothing. He had offered the wrong answer. After waiting for a long moment, the teacher spoke, scornfully. “Perhaps you have not really looked at it before.”

He turned away and said to someone else, “Come here. Your turn.”

The interior of the windmill was impenetrably black as Jacob stumbled, stung, back down the stairs.

That same light filtered through the barn’s high north window in a perfect, luminous blue rectangle, casting its radiance, though more dimly, upon the few objects that appeared in everybody’s still-life sketches: a bird’s nest, a cracked white pitcher, a loaf of bread. On Jacob’s third morning at the atelier, he woke early, determined to make a private search of the second barn. He wanted an original object for his own composition.

As he passed by the studio, he saw a few of the others already there, talking. He entered and pretended to set up his materials, straining to listen, to comprehend the knowledge of Gaugnot, the master who had studied with Rennes, and, through him, Renoir, and, through him, all the way back to Leonardo.

They were discussing Gaugnot’s instructions for the color wash—the next, exacting stage of the figure painting after the turpentine brushwork.

“Turpentine and pigment,” said George Carney, the class monitor.

“It’ll take weeks,” objected Lloyd, who worked in front of Jacob.

“He says,” Carney spoke with reverence, “that pre-painting is a required step.”

Lloyd fell silent.

At five minutes to nine, Gaugnot and Hannah drove into the courtyard in a little green Citroën. Nobody spoke as Gaugnot approached the barn, Hannah behind him. Carney jumped up and opened the door. Gaugnot entered, drawing the gaze of the entire class. Only Beth nodded at Hannah. “Good morning.”

Hannah smiled. “Good morning.”

Jacob also watched Hannah, although the others ignored her as she undressed and took her seat. Instead, they gathered around Gaugnot, their eyes fixed upon the small man with the goblin face who began to talk about “pathways.” Jacob struggled to understand. Gaugnot’s accent seemed especially strong today. After a time, Jacob made out that there were visible pathways in the surface of the body. You could trace them, Gaugnot said. He pointed to Hannah’s arm. “Here, and here.” Jacob squinted but saw only the dark luminosity of Hannah’s perfect skin. Gaugnot spoke of “structures” that one could see along the pathways. All things appeared mysterious, but the human body was comprehensible, its mysteries visible, through the existence of pathways, structures.

No one argued, no one even asked questions.

Jacob leaned toward Beth.

“You getting this?”

She held a finger to her lips.

At morning break, Lloyd offered Gaugnot a cup of hot water, but the master painter shook his head. He let Hannah make his tea, let her slice a wedge of lemon that smelled faintly of roses. The others turned away, envious.

Jacob left the studio and made his way across the yard, to the back barn. He was determined to impress Gaugnot by finding a special object for his still life. Surely Gaugnot would see and appreciate the effort; must he not be longing to look at something new?

But the back barn was filled with ancient and unpaintable things: enormous metal hooks with handles; knotted horsetails made of odds and ends of twine; a blacksmith’s anvil; oozing cans marked faites attention; sticks, snowshoes, harnesses; large rocks; rusted metal in innumerable scalloped and pierced and spoked and notched shapes; and, in the center of it all, a perfectly polished, red, pre–World War II John Deere tractor.

Jacob left the barn, discouraged. It would be better to find something simple.

Two months passed. No one moved quickly—not even those who’d been at the atelier for years—but in this group of perfectionists, Jacob became the standout of slowness. When he had set himself the goal of learning Gaugnot’s method in half a year, he had not expected the method to be so complex, so filled with elaborate and possibly superfluous stages.

In the daytime, he worked through lunch at his easel. At night, when it was impossible to work, he lay in his cramped French bed under a matted, scratchy blanket, his feet against the solid wooden baseboard, and he questioned himself. It was a hair shirt of a bed, and yet he kept under the covers because there were no window screens. The pressing darkness quivered with the whine of mosquitoes. Everyone ignored the insects; a local farmer’s wife might spend hours creating an elaborate, glazed tart and serve it en plein air, crawling with flies. He could not separate his frustration with the atelier from his frustration with the French countryside itself, and with Gaugnot—himself so very French—pointlessly exacting in some ways, yet theatrically oblivious in others: Gaugnot, whose little smile verged on smugness as he pointed at the beguiling curve of Hannah’s breast; Gaugnot who one afternoon, when he became annoyed, spat—accidentally or no—on a student’s canvas. Was this the classical education he had imagined? He had been deluded; he was a romantic. Sweating under his blanket, Jacob pushed away the thought that the position of his easel was unlucky, even cursed. Its former occupant, Bart Weiss, had quit the class, banished, perhaps, by Gaugnot, or defeated by the dreary, idle country winter. Perhaps it was the ghost of Bart that made his hand shake, his turpentine spill, a stray barn swallow mark his canvas.

He could ask Beth what had become of Bart, or he could ask Carney. But Carney rarely gossiped, rarely noticed anyone save during the daily positioning of Hannah, whose limbs he treated as if they were red-hot pokers and he were wearing oven mitts. It would have to be Beth. She typically took an extra ten minutes after class to clean her brushes and meticulously rearrange her easel, so one morning Jacob stayed behind and asked her to lunch. She put on her floppy hat, and they set off on the brief walk to the village restaurant.

As they passed the moats, he asked about Bart Weiss. Beth didn’t answer for a minute.

“What I mean is,” he persisted, “am I laboring under a cloud or something? Is my spot cursed?”

“You’re doing well,” she said. “To be frank, you seemed a bit at sea those first couple of weeks, but I’ve begun to notice a change. You really seem to have—”

He waited hopefully for her to explain the change. But she returned to the subject of Bart Weiss. “He was here longer than any of us. Seven years.” She frowned, clearly deciding how much to tell him. “Then Thomas told him he had to go.”

“Kicked him out of the atelier?”

“I suppose so.”

Jacob made a guess. “He slept with Hannah?”

Beth winced, but when she spoke, her voice was calm. “Thomas said that Bart had stopped learning.”

They approached the small restaurant in the center of the village. Jacob had already visited the place to view its collection of still lifes by former students. The painters, it was said, had revitalized the area. Certainly they had bought property; they frequented the restaurant; they drank the local wine. They purchased used cars and bicycles and microwave ovens and fans; they bought toilet paper and bottles of vegetable oil and bars of soap and left all of it barely used or half-finished with the locals, who kept things faithfully unused, or resold them, or finished them and recycled the containers. All of this activity, this consumption, the provenance of Thomas Gaugnot. Even outside the studio, Gaugnot was a force; he had created a local economy based almost solely on the idea that it was possible to give up one’s concerns, move to rural France, and dedicate one’s life to recovering the great age of painting. It was a cult, Jacob decided—and, as in a cult, the students abandoned their former lives, they tried not to trouble themselves with material concerns, they put all of their energy into following their leader. Jacob did not share these observations with Beth; from what he could tell, she was one of the cult’s most devoted members.

Now she switched easily to French, explaining to the proprietor that they wanted a table inside. She took every opportunity, Jacob noticed, to avoid bright light of any kind. Her easel was far from the window. Her old sun hat was lined with black under the brim. After they were seated and both had ordered the lunch special, she went on quietly, in English: “Thomas told Bart that in the development of every artist, there’s a turning point. A moment after which it becomes clear he has reached the end of his talent. He’s done as well as he can. And in the aftermath of this moment, every new work he does—everything he sees—becomes derivative of the work he was doing then.”

“And I suppose Thomas can see this moment as it’s happening?” Jacob could not control the sarcasm in his voice.

“Nobody can. Most often, the painter doesn’t know himself. And generally it comes after he’s made progress, done some of his best work. It can take years to see. But Thomas can usually see it before others can. Last summer, Bart painted a still life of red poppies. They’re not blooming yet; you’ll see them soon. But if you pick them right when they bloom, they last three days. Bart managed somehow to paint them in that time. Oh.” With a childlike movement, Beth set her fingertips against her cheek. “It was a glorious painting. What I wouldn’t give to have the ability to capture the poppies in three days. Although I hope I don’t stop there . . . Anyway, it became clear—clear to Thomas—that Bart would not continue past the poppies, so in the fall, when he posted the next year’s class—”

“Where do you want to stop?” Jacob asked, speaking to ward off the ever-present fear and resentment of Gaugnot that had ambushed him as she spoke. “After you learn to paint the poppies—?” Suddenly he knew. “It’s Hannah, isn’t it?”

A shadow of caution fell over the table.

“What do you mean?”

“Forget the still lifes. Secretly, everyone in class, everyone just wants to make a decent painting of Hannah.”

When Beth spoke, her voice was prim. “Hannah is with Thomas. She’s his muse.”

Even in this group—whose lack of irony flavored each conversation with unintentional nostalgia, who tossed around the word “beautiful” as if beauty was still of vital concern to visual art—he would not have believed it possible that any flesh-and-blood woman could be thought of as a muse, not without a snicker. And even more unsavory to imagine Hannah as Gaugnot’s muse, from Gaugnot’s private Tahiti. Not for the first time, Jacob felt the knock of his own desire.

The server stood above them, waiting for their attention. She placed before each of them an avocado half, pitted masterfully to reveal the graduated shades of green, its center a perfect puddle of quivering green olive oil.

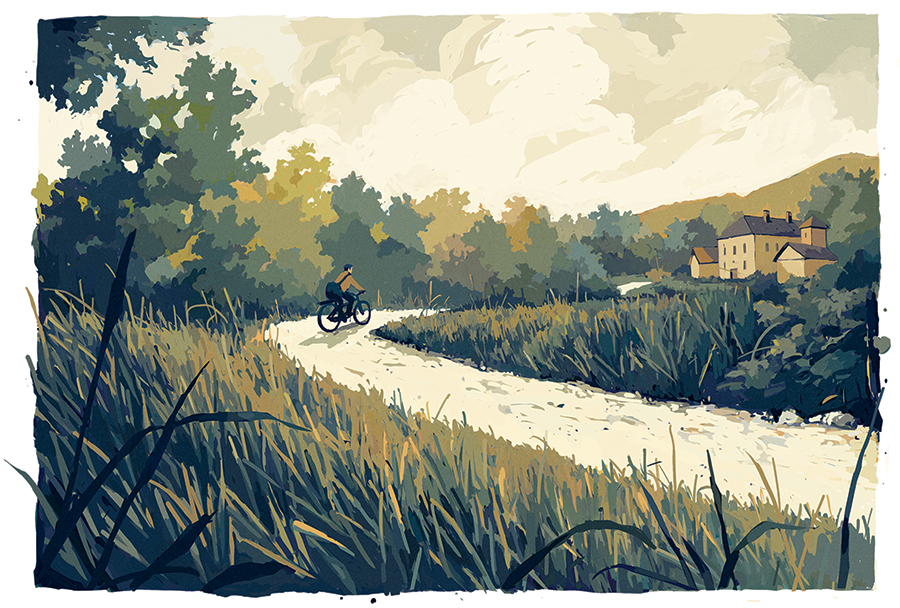

That Sunday, Gaugnot opened his house for tea. Beth described the annual event to Jacob as they rode the atelier’s rickety bicycles to the neighboring village where Gaugnot lived, “for privacy,” she said. There would be the sputtering electric kettle from the studio, lugged over by Carney for the occasion. There would be a decorative tin filled with biscuits that seemed always the same, and, if they were lucky, there might be a perfect tarte aux fraises made by a neighbor. The point was not to have tea, Beth said, but to page gingerly through Gaugnot’s sketches and notes, and to gaze upon the million dollars’ worth of Gaugnot’s paintings. His agent could get sixty thousand for a commissioned portrait. Most of the work that Gaugnot did these days was by commission; in the winter months, with the atelier out of session, he flew to the States, where clients posed for him.

She led Jacob to an imposing stone house near the center of the village. In the hall, she immediately became engrossed in conversation with Carney about the position of Hannah’s head. Beth told Carney he had turned her head slightly to the left, and Carney, uncharacteristically bridled, insisted this was not the case. Hannah stood with them. Occasionally she spoke a few words in accented but fluent English; she had grown up in Nigeria. Jacob noticed that although Beth looked at Carney with forthright insistence, she lowered her eyes when appealing to Hannah.

Curious to see the art, Jacob made his way into the sitting room.

From floor to ceiling, the walls were hung with Gaugnot’s paintings. Most were portraits and figure studies, displayed simply, although a few were in elaborate old frames that reminded Jacob of those in the Louvre. How had Gaugnot, a penny-pincher, procured them? Yet the paintings deserved the costly frames. They were richly colored, imaginative, beautifully lit. He poured a cup of tea and sat down opposite a large, fanciful still life of peonies, crockery, and what looked like a human rib cage on a table. He could almost see the ribs trembling with phantom breaths. After some time, he recognized the cracked white pitcher from the studio, made unfamiliar by the painter’s touch.

“May I sit here?”

Hannah stood before the chair he had been saving for Beth. Jacob nodded. She took the seat easily, as if she knew that she could have whatever she wanted in this house, but shyly, as if this privilege did not mean anything to her. She wore jeans, a white blouse, and worn flat sandals. To have her sitting so close to him, however clothed, made him uncomfortable. He stared at the ground, breathing in her scent of local lavender. She was, he knew by now, thirty-six years old, although she looked ten years younger; her age was apparent only in her feet, in the thickened joints behind her big toes.

He had never spoken to her. Had not needed to, as the months passed and he began to believe, with pride, that he had managed to evoke something of her radiance in his work.

He cleared his throat. “How long have you been modeling for him?”

“Eight years,” she said. When he said nothing, stunned by the length of time, she added, “I was in the States. I came to France after my mother died.”

She spoke as if she were explaining it to herself as much as to him.

“I’m sorry,” he said, automatically.

“I was a student here.”

Jacob tried to think. “That must be why you really know how to pose,” he said, finally.

“You seem very serious.”

He choked on a sip of tea. “I’m actually lost,” he said. Fighting down a flicker of pride, he heard himself say, “Where are the paintings of you?”

“In another room.”

“May I see them?”

“It’s the bedroom.”

“Oh.”

“Do you want to see them?” She was already standing.

Together they left the room. She led him up a flight of stairs. The staircase seemed forbidding, and narrow; he smelled a cold, damp smell, more ancient than mildew, emanating from the stones. At the top, she pushed open the dark, heavy-looking wooden door and entered, moving aside for him.

“Here they are,” she said, gesturing.

Jacob walked around the large room, trying to ignore the bed. Aside from several lamps, and a dresser, and a low seat upholstered with black-and-white toile, there was no other furniture in the room. The walls were covered with paintings, drawings, and sketches. They were undeniably erotic, all of them: the formal studio portrait featuring Hannah’s voluptuously lidded gaze; Hannah looking up from an uncomfortable settee; Hannah with a blue ceramic bowl of peaches; Hannah actually posed in the style of a Gauguin. On the wall opposite the bed was a large canvas. Hannah’s spreading thighs dominated the foreground. In the center of the painting, her vagina. Her torso was foreshortened, her head barely visible.

While Jacob studied them, Hannah stood next to him in silence. The paintings were splendid, all of them: masterful in their use of light and shadow. He looked at every work at least twice, but he could not take his eyes away from the painting opposite the bed. It felt exploitative, and yet he could not stop looking at it.

When the door creaked open, they turned quickly, as if they had been caught in an embrace.

“So here you are,” Gaugnot said.

“He asked to see them,” Hannah said, dropping her gaze.

The old man’s heavy eyelids flickered, or Jacob would not have known that he had heard.

“Wonderful paintings,” Jacob said. “I was admiring the light.”

“Yes.” They had a brief technical conversation in which Gaugnot ignored Hannah, explaining to Jacob that warm, interior shadows might seem less pronounced on a winter’s day.

Then he switched off abruptly. “We don’t usually allow students to see the room.”

He turned to Hannah. “May I speak to you?”

Jacob left the bedroom. The door closed firmly behind him. He descended the stone steps, his knees shaking from the shock of seeing the paintings, of being alone in a room with Hannah, of Gaugnot’s appearance.

Beth stood at the foot of the stairs. “Come on, Jacob,” she said, grasping his elbow with unexpected force.

She led him outside. She gestured with her chin, mounted her bike, and rode out into the lengthening, warm rays.

Jacob followed her. “Beth. Hey, Beth.”

Halfway to the atelier, he caught up to her. She pumped rapidly, her forehead faintly puckered, refusing to look at him.

“C’mon. What is it?”

“You shouldn’t have gone up there with her,” she said.

“Have you seen that room?”

“Once. He was out of town.” As they turned onto the long, uphill lane toward the atelier, Beth said, “He’s going to hold it against you.”

“Nah, no way.”

Breathing hard, Beth did not answer.

“He barely knows who I am. He’ll forget about it in a week.”

“He won’t.”

“He gets her wrong, you know,” Jacob blurted. The heat of truth rose into his throat. “There’s an elongation, a distortion in the shape of her body. And it’s more than that one distortion. There’s something missing in her face. He doesn’t see her.”

Beth, pedaling determinedly, said nothing.

High summer and they were living in a blaze of light. The wheat fields, the barley fields, the grazing fields, the hay fields with their stacks linked up like yellow beads. The sun was unbearable. You only had to stand in it for a few seconds to know it was dangerous. The sun was imperial; it was godly; yet, Jacob sensed the landscape and everything on it was like a slice of bread in a French toaster: scorched only on one side. The backside, the shadow side of everything, was moss and lichen, mold, deeply black.

But the light! The light! If only they could paint the light—so fickle, so impossible!

Only during their hours in the studio, lit faithfully by the cool light from the north, could they work peacefully, steadily; and yet even in the studio the light played its tricks on such ordinary objects as apples and ginger jars, revealing their utter strangeness. Hannah was, he slowly came to see, if not a muse, a superb model. There was a generosity, an understanding in her stillness. The light against her skin always patient and unmoving. Yet ultimately perplexing.

Jacob complained to Beth, “I came here hoping that if only I could learn to paint the world as I see it, then this would transform my work. So far I’ve learned that I can’t paint, and now I’m starting to think that I can’t see.”

But as the hot weeks crawled by, almost imperceptibly, things began to shift. He first noticed his progress as an increasing ability to pay attention. He forgot what he was doing for periods of time, and he forgot to worry. Gradually he stopped critiquing what he did, stopped noticing the other students: who was fast or slow, whose easel stood in a better spot. He arrived early in the morning, among the earliest, awaiting Hannah’s arrival with his paints ready. She was always on time; she had begun to say hello to him and sometimes to smile. In an effort to protect both her and himself, he had not spoken to her since the party. He worked hard all day. In the evenings, after supper, he rode his bike around the countryside, and upon returning, he showered and dropped off to sleep.

Gaugnot rarely spoke to him now. He worked almost entirely without individual instruction; instead, he learned from listening to Gaugnot’s brief comments to Beth, on his right, and to Lloyd. Submerged as he was, he rarely thought of much other than painting. He did notice that Gaugnot and Hannah did not arrive together anymore, that Hannah was riding her bike in the mornings and not seated in Gaugnot’s little Citroën. There had been some kind of argument, he suspected. Working through the two-hour lunch break, he sometimes caught a murmuring thread of conversation between Hannah and Beth. They sat under the live oak tree, many yards from the window, but when the wind came in a certain direction he could hear them talking. “She painted that green bowl . . . ” “He was afraid of chickens . . . ” They seemed to talk almost entirely about former students.

His visit to Gaugnot’s house had changed his canvas. So had seeing Gaugnot’s paintings—so vivid and skillfully done, so enviably finished. And yet, he told himself, somewhat fatuously in the middle of the night, that what he’d said to Beth was true: Gaugnot did not know Hannah. The paintings of her were not complete.

As the summer burned toward its final days, he began to secretly believe that his own painting might rival, even surpass, his classmates’ paintings of Hannah. He had no way to know for sure. He didn’t ask Beth for her opinion. She kept her own easel turned away. He refused to ask Thomas. But he began to wonder if the man’s very silence was a sign of respect. Jacob had watched his teacher dab a loaded brush onto his classmates’ paintings with the contemptuous insouciance of a graffiti artist. But Gaugnot did not lay his brush upon Jacob’s painting of Hannah. He avoided it, and Jacob, as if he couldn’t bear the sight of either. Jacob had noticed as an undergraduate in art school that professors dismissed the students who had already failed; it was as if they could not bear the sight of their disappointment, their downward fortunes. But the professors saved their most virulent dislike for the students who rejected them: those who moved on, to another school, another teacher, another realm. Those who didn’t need them or their teaching.

Each morning it was Carney’s responsibility to set Hannah’s pose. To aid both of them in this challenging task, Carney taped the places on the floor and the chair where her feet, her hip rested. He kept track of the position of the light on her body, marking the shadows on a sketch he had made of her. But it was impossible, even for Hannah, to sit in one position for months at a time. Gradually, subtly, the habits of her body surfaced.

It was a month after the visit to Gaugnot’s house, yet Beth and Carney continued their argument over the pose.

“Her head. Her head is in the wrong place.”

Carney brought out his sketch and showed Beth: there was the point that the shadow had cast on Hannah’s cheek.

“It’s not right,” Beth insisted.

Jacob preferred Beth’s angle; it was better for his own painting when a certain shadow dipped into the hollow under her throat, between her breasts. He had, over the last weeks, become attached to that shadow, as much as to the shape of her breasts. Moreover, Jacob thought, Carney’s pose, the angle of the neck, was uncomfortable. Carney did not seem to see this; Beth, who noticed everything about Hannah, did.

“Look,” Jacob said finally, holding up a drawing from his first week at the atelier. “Look at this sketch. The shadow on her cheek is here.”

Gaugnot’s thickly accented voice broke into their conversation. “No, no,” he said, and there was something playful but malicious in his tone. “You are wrong.” He prodded Hannah into the more uncomfortable position. “It is here.”

For a long moment, Hannah held still. Then, almost undetectably at first, she began to quiver. The painters stopped working, frozen at their easels, stricken by her irregular trembling, her fluttering breath, like the sound of the doves in the eaves. Hannah shook. She fought back sobs. She wrenched herself out of the pose and, snatching up the white robe, ran out of the studio.

Jacob looked at Beth. She stood with her head averted and tears in her own eyes.

He bounded out the door. Hannah had neared her bicycle beneath the oak; he had almost reached speaking distance when she placed one foot on the near pedal and swung her leg gracefully over the back wheel. Jacob turned and raced to the barn where he kept his bike. By the time he returned to the courtyard she was well ahead of him, her white robe fluttering behind her.

He followed the vanishing speck of white. She took the south road out of town, past two cow pastures and a field of mown hay. The road was on an incline, and it was almost a kilometer before his voice reached her. “Go away,” she said. He thought of the stricken studio. “Hey,” he panted. “Give me a break.” Almost imperceptibly, she sped up. He was out of breath and did not try to speak again. She veered right after another cow pasture and rode down the long hill toward the stream, then up a short rise. There she turned down an unfamiliar road and Jacob, mystified, followed at a greater distance. She seemed to know exactly where she was going. They passed a house with chicken pens and a barking dog, then rode along the crest of a long hill, from which Jacob could see, to his right, a bluff and then a series of fields and trees, golden and dark green, gradually shading to the horizon. Before them, a small stone chapel appeared. Hannah dismounted. She leaned her bike against the chapel, climbed the two stone steps, tugged open one of the heavy wooden doors, entered, and shut the door behind her.

When Jacob reached the little chapel, he leaned his bicycle against its wall. Above the door, a gilt sign read chapelle du st. francaire. He sat down on the steps. From this vantage point he could see, twisting among the trees below, a creek. Beyond it, a perfect field of yellow wheat, moving into the layers of green and gold. His breathing settled, things grew altogether silent. Beyond the field he glimpsed a pasture and cows, then the red-tiled roof of a dilapidated barn, and beyond that the turrets of a small chateau. The landscape held the still detachment of a dream.

It was perhaps half an hour before the door behind him creaked open. Hannah sat down next to him. The white robe was pulled tight and knotted around her waist. She seemed chastened and calm; he wondered if she had been praying.

“I’m in rural France,” he said. He had just now begun to believe it.

She said, “The chapel was built for a local saint.” He nodded but could not think of a response. After a moment, she added, “It’s built over the site of a perpetual stream. I’ll show you.”

She stood up and gestured to him. He got to his feet, his muscles protesting, and followed her behind the chapel and down a steep path that switched back and forth until they reached a cairn. The stones shielded a mossy, tiny trickle of water.

For quite a while they stood before the little cairn. Jacob read the inscription in French, please respect this source.

Hannah said, “The locals have always felt it was a holy site. The water from this stream never stops. About a hundred years ago they built the chapel, but sometimes they hold services here.” She pointed to candle drippings on the rocks.

“How did you find it?”

She shrugged. “I’ve had a lot of time to ride around, when Thomas is painting.”

“How did you get involved with him?”

She knelt to dip her fingers in the stream. “It’s hard to explain.”

“What are you doing here?” Jacob persisted. “Why here? Why with him?”

She shrugged again. After a moment, he knelt beside her.

“It was eight years ago,” she said. “I was at loose ends. My dad was far away, my mother had died, and she was estranged from our family in Nigeria, I barely knew them. I had an undergraduate degree in painting—and I heard about Thomas. I had some savings, so I came to study with him.”

“And then?”

“After a couple of years, I ran out of money.”

He turned to look at her. She had pulled her hair back into a thick braid, and he could see her features clearly. She looked out at the layers of green and gold, and he examined her familiar profile in the light.

“He started paying me to pose after class. He was working on a figure drawing and then a painting. It took months. He never said a word to me, the whole time. During breaks, I would drink tea by myself. After a few hours he would bring his brushes to the sink, and I would leave without saying goodbye. There was another model at the time, Bianca. She was my friend, and we would talk in class, during the breaks. But he never asked for Bianca. I thought he must like me because I could hold a pose. I never asked him if I could see the painting. Of course, I was afraid of him. I could feel it—that thing people talk about, that kind of influence. Then one day, he took me by the shoulders and set me in front of the painting.”

“The paintings don’t look like you,” Jacob interrupted her. “Even the formal portrait. It’s a good painting, but it doesn’t look like you. Doesn’t capture you—” He stopped, troubled by his choice of words. He had spoken as if she were a fugitive. “What happened then?” he asked, although he had a feeling that he knew.

“I thought he would ask me whether I liked it, or whether I thought it looked like me, but he didn’t ask me anything. I wasn’t even sure why he wanted me to look at it. And then he said—” She paused and closed her eyes. Over the past month, Jacob’s desire for her had reached the point where the mere sight of her eyelids made him want ardently to kiss her, but he could not do it.

“What did he say?” he asked.

“He said that I could stay here, as the model, for as long as I wanted. And that he would give me room and board in exchange.”

“You’re a—” Once more, Jacob struggled against the thought, “a captive.”

“I tried to leave once,” she said. “I thought of writing to Bianca to borrow money for a plane ticket. She would understand. But when I talked to Thomas—”

“He was upset?”

“No, that’s the thing—he became so calm when I talked about leaving. He said he knew I wasn’t going to leave. He said that he had already seen it.”

“What do you mean?”

“He told me all of this has already happened.”

Jacob waited a few seconds. “Do you mean,” he prompted, “in a former life? That you and Thomas are lovers reincarnate?”

“No.” She frowned, touching her fingertips to the spot above the high bridge of her nose where, Jacob had noticed, faint vertical lines were visible only in the mornings. “He said that this whole world has already happened. That we had always been, and would always be, lovers, and that we would make love again and again; that everything we’ve done exists in a kind of continuous loop that replays itself, over and over. Somewhere, it already exists. The bedroom I had, in our old house, before my mother died—I had told him about my bedroom and our house—somewhere on the loop, it still exists, and I am still five, it’s still my room—”

“That’s eternal recurrence,” Jacob interrupted her. “From Nietzsche. Among others.”

“Well, I thought it was dopey,” she said, smiling ruefully. “It seemed all right, all of a sudden, to make him happy, to stay with him a little longer, silly man.” The line between her brows deepened. “But that happened before I knew I was no good,” she said. “I still thought I was going to be a painter.”

She laid her long-fingered, graceful hands on the pointed stones of the cairn, touching each one gently. Jacob raised his eyes above the cairn and let the light blind them, splinter them with sunspots and sun devils and floaters and blue beams. “It’s Nietzsche,” he repeated into the blindness. “Eternal recurrence. But Thomas is ignoring the important part.”

Nietzsche had made it into an ethical question: What kind of life do you live? If a demon came to you and asked, “Would you live your life again?” what would you decide? Jacob envisioned his mother hoarding her notebooks of small sketches, she who had been so set against his going to art school.

“After everything that happened, it was too odd for me to stay in the class,” Hannah said. “Anyway, I wasn’t very good.”

A silence followed her words. Jacob took his eyes away from the sun and looked toward her. He felt an overmastering impulse to reach for her, to feel her mouth press warmly through the fiery circle where the sun had been, her body against his. But something held him back. It was not fear of consequences or even caution. Instead, a confusing tenderness filled him. He gestured toward the chapel and their waiting bicycles.

Every day, through the months of August and September, when the class broke for their long lunch, he got onto his bicycle and met with Hannah at the chapel. No one asked them what they did. They never saw anyone coming up the hill.

Inside the chapel it was cool and dark. Someone did come by when they weren’t there, someone dusted the pots of plastic flowers that surrounded a statuette of the saint, someone placed glass vases of Peruvian lilies at the gated front of the chapel and at the statue’s feet. They blocked the door shut with their bicycles, and Hannah covered St. Francaire’s face with her sun hat so that the saint would not be offended by their using the chapel as a place to eat and talk. She was always chilly in the chapel, with its stone floor and thick walls. Jacob, in a fit of tenderness, brought one of his ragged sweaters for her. She spoke about her mother’s illness and about her father in Nigeria, whom she had not seen since childhood and felt she could not ask for money. He told her about his own parents, who had lost their shoe repair business, and whom he had disappointed so baldly and so thoughtlessly that he couldn’t bear to speak to them more than once every couple of months. He told her about his lack of early artistic training and his own struggle with painting, of how he, too, had known that sense of being no good; but he was too ashamed to speak of his ambition.

Each day, he emerged from the chapel to a delicious feeling of distance, looking over the fields and trees and, far away, the tiny, flightless windmill. At night, when he woke fitfully to scratch his insect bites, their conversations preoccupied him. All of their long hours became one.

The weather turned, and the painters began to wear fleeces and woolen socks. Jacob thought he might find a part-time job on a local farm, remain in France over the winter. He might somehow stretch his savings, stay at the atelier, for years. It seemed essential to be present, to make more paintings of Hannah. He felt as if he were on the brink of understanding.

In his final weeks on the painting, he felt a growing sadness throughout his body. The mornings were still radiant and the light of the sun thinner but still golden. One morning in early October, the sky was leaden. Through the gray fog, an intense damp pervaded; the world had turned upside down again; coldness, wetness, darkness, had emerged. Jacob pulled on his overcoat before setting off across the scruffy courtyard for the studio. There he would make tea, get out his brushes.

He arrived at the barn to find, posted on the door, a sheet of paper. It was the list of students Thomas had accepted for the following year. His name was not among them.

“Are you in love with her?” Beth asked.

They were alone in the studio. After a moment, Jacob missed the scraping sound of her palette knife. He waited until the sound began again before he replied.

“Sure,” he said. “Sure, I’m in love with her.”

Beth was making rich, luxurious piles of green paint. Dark green this time, the color of the magisterial, dry-leafed oaks against the bleached yellow fields.

“What are you going to do about it?”

But must one do something about an emotion, once it had been identified?

“She’s older than me,” he said. This was true, although he felt that he was lying.

“And there’s Thomas,” Beth added, mounding the dark heap with her knife.

But they both knew that Jacob had no reason to try to please Thomas now.

Beth piled half of the glossy dark green into a tube, then squeezed a dab of cadmium yellow into the remaining pile and began to scrape and mix again. Jacob bent to his work, relieved the conversation had ended. But presently, Beth spoke again. “Will you take her with you?”

Was she pushing the palette knife a little harder than before? Jacob put down his brush. Beth’s lips were pressed in a line. There was a pink spot in her cheek.

Cruelty rose, pushed away shame. “Why don’t you leave and take her with you?”

Beth’s arm jerked across the paint.

His friendship with Hannah had been possible only because of Gaugnot. Gaugnot commanded every circumstance, and Jacob was now banished; there was no point in seeing it any other way.

He finished the painting two weeks later. In those final days, seeking light and warmth, they ate their lunches outside the chapel. The fields had faded to layers of brown and ash-blond. She was right there with him and he wasn’t afraid of what would happen next. In truth, he was invulnerable. Nothing—not Thomas, nor even Hannah—could touch him. He would return to New York, and this time he would succeed. He need never lose these seasons in France, these rides to the chapel. The conversation near the cairn, the eternal spring. He knew he could return to this, again and again. It would exist forever. Anyway, he had the painting.

He told himself that he would always keep the painting. And he managed to hold on to it for years, although upon his return to New York he fell into a predictable and seemingly endless trough of financial desperation. He had been in France for only half a year, and yet many elements of his old life had changed or vanished. Charlotte lived upstate now; she had stopped teaching and was engaged to a neurologist. Their old building had been cleared out, to be redone as condominiums. Everyone was leaving Manhattan; it was becoming a clean, orderly space for new people and new businesses. Jacob got a job as a waiter at a new restaurant to pay the rent on a studio deep in Brooklyn; he fought against a terrible artistic emptiness for more than a year; finally he returned to his old abstract work. He threw himself into this effort to the point of exhaustion, and he didn’t phone his parents or give them his address. He made mistakes at the restaurant. He was fired from that job; he moved, again and again, from a one-room walk-up to a share, to a rooming house, and then into his unheated studio.

Finally, he was obliged to leave his studio. On a bleak evening in late winter, while cleaning out his things, he came across, as if anew, the canvas. The image was breathtaking. Her hair, the light upon her dark skin, the shape of her body, appeared unreal, even mocking. It was all more lovely than what could be imagined or untrue. Examining the painting, he knew his pointless study of technique had met, in this one instance, a subject worthy of such faithful representation—knew it was only Thomas’s obsession with technique that had made it doable. He began to wonder whether his reimmersion in abstract work, in any art, would be merely a long and self-deluded aftermath of this one painting.

The following autumn, when his new abstract work—which he understood to be empty, belabored, hard-edged, and lacking love—had unexpectedly found him a downtown Manhattan gallery, and then a one-man show, and suddenly an agent, he received a postcard from Beth. It had been forwarded twice, and after months had finally reached him at the gallery. He stood for an eternity on the street, deciphering and rereading her tiny script. In the spring, with the departure of Carney, she had moved her easel to the best spot in the studio. In June, she had finally learned to capture a red field poppy in its three days of life. “Also,” she wrote, “Hannah and Thomas have had a child, a daughter, Angevine.” In the dark time that followed the receipt of the postcard, Jacob shoved the painting of Hannah behind a stack of new canvases.

Months later, forgetting what he had done, he showed the stack of canvases to his agent. When she came upon the painting of Hannah, she let it sit before them for a moment. Jacob saw a pulse twitch in her throat. Then she recovered herself.

“What am I supposed to do with this?” She laughed, and added reluctantly, admiringly, “Although, it is beautiful.”

“Do what you do,” he said.

The agent brought the painting to an auction where none of the clients would know Jacob’s reputation as an abstract painter. It sold immediately, for sixty thousand dollars, to an anonymous buyer from Europe. In the years that followed, although Jacob tried repeatedly to buy back the painting, and as the auction value of his abstract canvases grew to match, and then surpass, that sum, he was unable to trace the buyer.