A late-nineteenth-century thangka of Padmasambhava: mineral pigments, Chinese Qing brocade frame, silk dust cover (detail). Courtesy the National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Arthur M. Sackler Collection, the Alice S. Kandell Collection, S2013.29.4

The eighth-century Buddhist tantric master Padmasambhava is thought to have been the first to describe a beyul—a place where the physical and spiritual worlds collide. These hidden valleys are buried among the Himalayas of Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, and India. Some are tiny; others are hundreds of square miles. But the belly of each comprises an ambrosial, parallel dimension, limitless in divine and earthly delights, and accessible only to true believers, as the Holy Grail was to Lancelot. One could stand smack in the middle of a beyul without knowing it existed. Nobody is sure how many exist, but the working theory is that there are one hundred and eight.

Believers unlock beyuls in times of great stress or upheaval. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Sherpa people of the Minyagpa, Thimmi, Sertawa, and Chawa clans were forced to flee their Tibetan homes and cross the treacherous Nangpa La pass into Nepal, where, depending on whom one believes, a hunter or a trio of friends revealed the beyul of the Khumbu Valley, just a few dozen miles from the royal city of Kathmandu. The migrants established an agrarian paradise on the southern slopes of Chomolungma, the “mother goddess of the world.”

Emigrés from powerful and fractious regions flocked to Nepal, a spleen roughly the shape and size of Tennessee, in search of their own beyuls, farming on loam that welcomed almost any crop—especially cannabis, a bulky, dioecious herb that could be grown for food, medicine, rope, roofing, oil, clothing, and, when smoked as fresh buds, hand-rolled resin charas, or hash, a potent high. Nepalis had cultivated cannabis before almost anyone on earth, and it is described in a Hindu text as a “liberator.” The deity Shiva was reportedly a stoner, and devotees honored him by stuffing charas into clay or stone pipes called chillums, and entering psychotropic trances. Each year Nepalis have held a festival called the Maha Shivaratri, “the great night of Shiva,” upon which almost everybody in the kingdom gets baked.

In the Sixties, Western beatniks hopped in rattletraps and headed east from Europe through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India to Nepal along a so-called hippie trail, buying charas from state-licensed stores in the capital, Kathmandu. The Beatles ditched England for an Indian ashram, and Jimi Hendrix wrote “Purple Haze,” which was widely believed to be about a euphoric strain of cannabis whose buds were stained by water-soluble pigments called anthocyanins. But in 1973, under pressure from the United States, King Birendra of Nepal outlawed trade of the plant, and in 1976, he banned cannabis outright. His authorities shuttered dispensaries, forced the hippies underground, and torched farmers’ yields. Rural Nepalis starved, and the use of hard drugs soared. Maoist rebels bivouacked in valleys beyond Kathmandu, promising to topple the monarch and his parliamentary cronies, and install an egalitarian people’s republic. Their stronghold was a town named Thawang, in a district called Rolpa, nestled in the rocky Annapurna massif, and they won the support of millions by preaching class emancipation—or, if that didn’t work, emancipation via kidnapping, kangaroo courts, and bucket bombs.

In 1996, the insurgency became a civil war. Anyone associated with the establishment lived in fear of torture or death. The United States, which had backed Birendra during the Cold War, assisted him again with military training and assault rifles. Close to midnight on October 23, 2002, the war arrived in Punarbas, a remote jungle spur in southwestern Nepal that jabs into the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Around thirty Maoists surrounded the home of Megh Bahadur Koirala, a tall, debonair pharmacist and a representative of the ruling Nepali Congress Party. Some carried machine guns, others rods and blades.

“Bhai,” one of them called, using a term of endearment meaning, roughly, “brother.” A relative was seriously ill, he added, and in need of medical attention.

Megh, sensing danger, demurred. “I’m not coming out,” he said. “It’s very late.”

The rebel dropped his ruse. If Megh didn’t step outside, he yelled, he would toss a grenade through the window, killing everybody within. Left with no choice, Megh opened his front door.

Several hundred miles east, in the city of Biratnagar, Megh’s twenty-year-old son, Madan, lay in a crowded jail cell, shaking and sweating in violent withdrawal. It had been a decade since Megh left Madan’s mother, Jhula, for a younger woman—his third wife—and Jhula had since slipped into depression and alcoholism, dispatching her only child to his mamaghar, the home of her brother and sister-in-law. But he fared no better than his mother, graduating from cough syrup to heroin, which he injected from syringes with HIV-infected needles. Jail had become his second home, and that evening, as he struggled to sleep, Madan began to believe he’d never get clean. When he did drift off, he dreamt that he uprooted a giant water tap from the mamaghar and hauled it up a hill on his shoulder—a premonition, according to local belief, of death. When he woke to find family members gathered around his cell door, he knew why they were there.

The Maoists, they told him, had dragged his father to the main square with a plan to break one of his arms or legs. But six years into the war, battlefield discipline often devolved into fraternal grudges. Megh had dished out long prison terms to rebels, and revenge was in the air. As neighbors cowered in their homes, one of the Maoists ran a blade across Megh’s throat and severed his head. Nobody dared recover the body until dawn.

Madan traveled to Kanchanpur for his father’s funeral. He wore white and shaved his head, as custom dictated. But when he bowed in respect, everybody—including his grandmother—ignored him. So he got high, neutralizing his shame and grief with heroin.

Travelers on the hippie trail in Afghanistan, 1977 © Bruce Barrett Photography

A bus on the hippie trail outside Kathmandu, 1976 © Jonathan Benyon

Madan left Nepal soon after, embarking on a prodigal Himalayan quest for meaning. By the time he returned, in 2010, the country had abolished its monarchy, and a Maoist was prime minister. But weed was still banned—even as Western nations, including the United States, began to lift their own prohibitions on the drug. Today Madan is sober, with a wife and child and a commitment, half a century after Birendra’s edict, to legalize cannabis in Nepal. Madan calls himself the country’s first “weed influencer,” sharing pro-legalization content with thousands of social-media devotees. He has organized protests and political stunts that have earned him stints in jail—and top billing on the evening news. Beyond that, Madan wants to recover native cannabis strains, or landraces, from all seventy-seven of Nepal’s rugged districts, unlocking his own beyul twenty years after his father’s violent death. “The mother plant is from Nepal,” he told me. “If marijuana is legal, the world will be in peace. I can feel it.”

In September 2022, I joined Madan on a leg of his odyssey from Kathmandu to Thawang, the onetime rebel HQ. It would be a chance to meet those who’d most suffered from both the ban and the war, he told me. And besides, he added, it would be fun. We met on an oppressively hot morning around nine o’clock, in a western suburb of the capital so full of dust and car fumes that the air scowled a leaden gray. Madan is flinty-eyed, with a saturnine grin and a uniform of bright tees and skate shoes that belie the youth he is trying to reclaim from heroin. Friends call him “Joseph,” owing to his mother’s Catholic upbringing—but he’s more properly understood as an oddball messianic figure, preaching the green gospel to thousands of disciples across Nepal.

Chief among them is Dipesh Karki, a skinny forty-two-year-old with dreadlocks and a Midwestern drawl acquired while working at a Taco Bell in Wichita. The pair first spoke last May, when Madan blocked the prime minister’s motorcade with a banner reading legalize weed, and spent nine days in jail. They had a lot in common. Dipesh had left the United States in 2007 to open a burger joint in Kathmandu, but a series of ordeals—in addition to heroin, the 2008 financial crash, a devastating 2015 earthquake, the bipolar disorder he struggled to manage—had, by 2020, left him jobless and suicidal, “the saddest person in the whole world.” In desperation Dipesh traveled to a remote mountain ashram, meditated—and smoked pot. “I had fucking alprazolam, lithium, I-don’t-know-what-the-fuck-fast- release, little-release,” he told me. “And now? I know what will make me high or mellow. I know my weed, I know my medicine.”

Science has yet to prove that cannabis is an effective treatment for opioid addiction, and Dipesh admits he has replaced one vice with another. But he is convinced it’s a “good” one, and that Madan is the man to deliver it to Nepal. Having exchanged messages for a while, the two vowed to join forces. Madan had clout and knowledge; Dipesh had money and a vehicle. Together they would drive across Nepal collecting landraces and making weed-based viral content, like a Himalayan Cheech and Chong. Madan’s campaign would reach new corners of the nation, while Dipesh would have something he hadn’t experienced in years: purpose.

Madan led us to a truck stop where Dipesh was parked. His baby-blue Mahindra SUV had a decal reading chill bro on its rear window, and heavy metal blasted from the stereo. He greeted me with a hug and offered me a joint. He was “working for the plant” as a “quality manager,” he joked, with a treacly nicotine smile. “I smoke—I assess.” We stocked up on gas, off-brand energy drinks, and fistfuls of gutka—a carcinogenic potpourri of tobacco and betel nuts—and joined the morning traffic. As the crow flies, Kathmandu and Thawang are separated by less than one hundred and fifty miles. By car it takes two days. We had barely left the city before events descended into a wild and entirely predictable chaos.

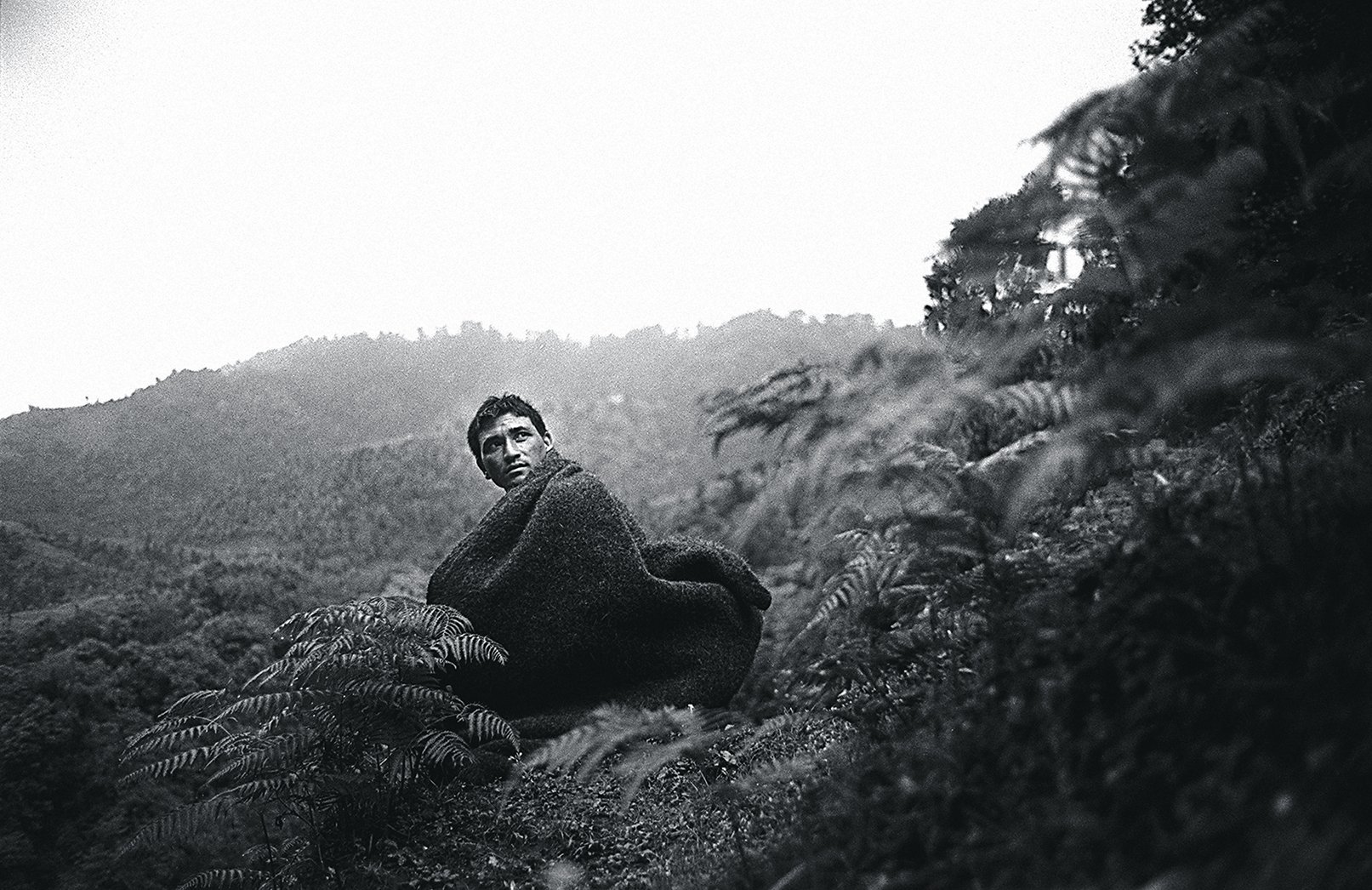

A Maoist rebel in Thawang © Moises Saman/Magnum Photos

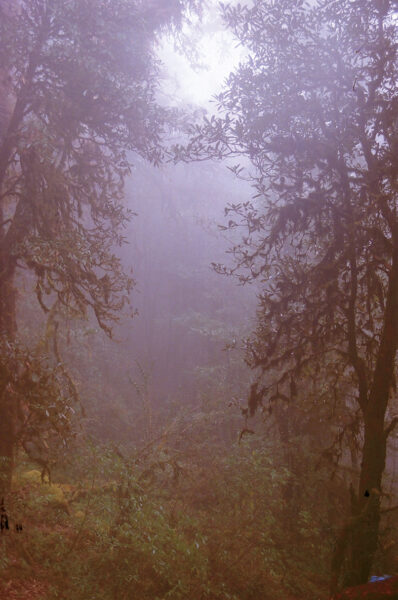

“Annapurna, Nepal” © Bastiaan Woudt. Courtesy the artist and Jackson Fine Art

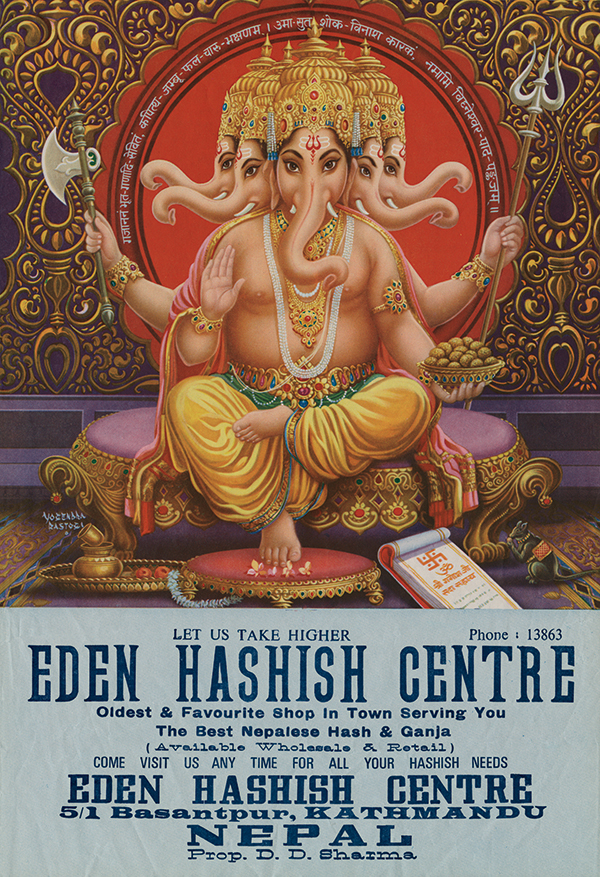

Nepal laid the foundations for its cannabis tourism industry in 1961, taxing and licensing drug sales from Kathmandu stores that became the talk of the hippie trail. The Eden Hashish Center, the Cabin, and Central Hashish Store, among others, lined a skinny thoroughfare named Jhochhen Tole, or “Freak Street.” A couple of bucks was enough to eat, sleep, shower, and get wasted on some of the best pot on the planet. Each outlet curated a psychedelic menu of fresh buds, brownies, opium-laced joints called “Chinese Crackers,” and, of course, charas, which was typically packaged as a conker-size “temple ball” of hand-rolled resin. “Anyone who has smoked Nepalese hash will never forget their first time,” wrote the American weed trafficker Joseph R. Pietri. “I remember mine: the rush was so strong I had to sit on the floor and hold on.”

Charas prices rocketed, and farmers diverted production from other crops to keep the hippies high. But their connection to Nepal was only so deep. They described Nepal not as a beyul but a Shangri-la, and called Chomolungma, the world’s highest peak, by its colonial name, that of a nineteenth-century Welsh surveyor who had never seen it: Everest. Wealthy thrill seekers delivered Sherpas back across the Nangpa La as porters. Only a handful of elites got rich off the green rush, and poverty in Kathmandu grew. “The filth, the naked children, and the women sitting on pavements, fondling infants,” wrote a New York Times reporter, “are somehow brushed aside.” By 1972, cannabis was the second-largest industry in western Nepal, and an illicit market transformed cities and towns on the Indian border—Nepalganj, Biratnagar, Kanchanpur—into smugglers’ paradises. Farmers complained that they were getting lowballed by brokers and corrupt politicians, but bigger trouble brewed. President Richard Nixon had inaugurated a war on drugs in 1971, and extended it via the United Nations as an anticommunist rallying cry. Sandwiched between Maoist China and non-aligned India, Nepal was a key target—not least because its capital city was awash with pot-smoking American refuseniks. The domestic affairs aide John Ehrlichman warned Nixon about anti-Vietnam protests in Kathmandu. “The communists and the left-wingers are pushing the junk,” Nixon told him. “They’re trying to destroy us.”

A poster advertising the Eden Hashish Centre in Kathmandu, circa 1967 © Aymon de Lestrange/Bridgeman Images

In 1973, Birendra’s ban went into effect, and he dispatched military squads to burn the crop wherever they found it. (A $3 million White House compensation package is rumored never to have made it beyond the walls of the king’s spanking new palace.) Freak Street’s hippies were sent to India, and farmers who had chased the green rush were left with nothing.

“It’s the poorest of the poor who would go to the truly marginalized terraces and grow cannabis,” Kanak Mani Dixit, a Nepali author and publisher, told me. “So you’re poor to begin with—and then that little source of cash income you had, that got taken away from you.” For centuries, Nepal’s kings had resisted the colonial yoke, but many saw Birendra’s cannabis ban as imperialism by proxy, erasing an ancient pillar of the nation’s culture. The court issued an unofficial amnesty every year for Shivaratri—but that made little sense. “It’s incongruous that you allow it on the holiest day, but you don’t allow it the rest of the days,” said Dixit.

In 1979, as Iran’s Islamic Revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan killed the hippie trail, Birendra cobbled together a crop-substitution program. But it was far too late. Farmers became black marketers, and heroin-smuggling caravans snaked along ancient Himalayan passes. U.S. State Department officials warned that Nepal was fueling a global opioid crisis. Nepali envoys and even royalty were accused of smuggling drugs in diplomatic pouches, while several U.S. heroin rings were found to have emanated from the kingdom. In 1986, five riflemen from Nepal’s famed Gurkhas, a unit of the British Army, were arrested at London’s Heathrow Airport with the drug stashed inside false luggage compartments.

That September, the Nepali journalist Padam Thakurathi published an exposé in one of the country’s largest newspapers, promising to name high-ranking officials involved in drug trafficking the following week. Days later, a would-be assassin broke into Thakurathi’s home and shot the sleeping writer at point-blank range. The hit failed, but Thakurathi lost an eye. A subsequent investigation triggered the arrest of Nepal’s former police superintendent, who was charged with accepting bribes from drug traffickers—as well as the arrest of a key royal aide and military leader who owned six homes, a fleet of taxis, and land worth $7 million.

In the Seventies, virtually nobody in Nepal took heroin. By the late Eighties, the country’s rates of addiction had soared. In Biratnagar, where Madan was raised, it was impossible to ignore the groups that gathered along the city’s sole blacktopped highway—or the way people shunned them, as if they were stray dogs. Madan never imagined for a moment that he’d join their ranks. Until the age of eight he lived comfortably with Megh and Jhula in a wooded village several miles north of town. His parents were an odd couple—Jhula short and fiery; Megh gangly and regal, a man neighbors addressed by the honorific “Uncle Doctor.” But they were happy together and, thanks to Megh’s landowning family, wealthy.

Even when the pair split, and Megh eloped across the country to Kanchanpur, Madan felt privileged. “My life was pretty chill,” he told me. “I was childish, you know—playing happily.” But as he grew older, he felt a deep emptiness that no amount of play would remedy. First he smoked cigarettes and drank alcohol, then he smoked charas. At a 1995 festival, when he was thirteen, he downed a bottle of cough syrup. He was “excited and overenergized,” he told me. Soon Madan was smoking brown sugar, or junk, a cheap, semi-synthetic mix of heroin, chalk powder, and zinc oxide. Then he began injecting it.

The following year, Maoists marshalled by an agricultural graduate known as Prachanda, or “the Fierce One,” elevated guerrilla attacks to a people’s war, demanding an end to the monarchy and Nepal’s semi-feudal economy. Thousands of rural Nepalis joined their ranks, vowing to kill millions and hoist the hammer and sickle atop Chomolungma. In 2001, when an intoxicated crown prince shot and killed Birendra and eight other royals, Prachanda, sensing discord, upped the ante, firebombing infrastructure and killing civilians.

Biratnagar suffered more than most cities. Its population was broadly procommunist, and royal soldiers and police responded to violence in kind. As a boy, Madan had idolized the Bollywood cops he saw on TV, and when officers rolled through town he would sidle up to them and try to lay a hand on their machetes, hoping some hero magic might rub off on him. But it didn’t—and as Madan’s addictions deepened, his goals dwindled to just two: get high, and get the money to get high. Pretty soon his idols were carting him off to jail cells for stealing, and he was on a path to becoming precisely one of the villains he’d despised in those grainy old films.

Even after his father was killed, Madan couldn’t summon any retributive energy, and while Megh’s neighbors joined soldiers to massacre twelve of his killers, Madan did little besides sketch out his next hit. Jhula’s alcoholism worsened, and there was little in Biratnagar beyond privation and petty crime. When he got a spot at a drug rehabilitation center in Delhi, Madan bused eight hundred miles of highway to begin a new, if not yet clean, life.

It is near-impossible to imagine that vacant, unscrupulous Madan today. As we left Kathmandu, and tarmac gave way to jungle roads and towns flooded ankle-high with monsoon rain, Madan received hundreds of calls, texts, and social-media notifications. Several times a day, he posts a blend of family photos, pro-legalization monologues, and lip syncs to traditional Nepalese music to Facebook, TikTok, and Snapchat. He has more than eight thousand Facebook followers, and some videos have reached nearly five hundred thousand people. It’s a great way to “sensitize people to marijuana,” he told me. At ten o’clock that night, in the city of Butwal, around a dozen young men had gathered to greet us in the lot of a gimcrack hotel, mobbing Madan as if he were a touring rock star.

Most of them, he told me—if not all—were among Nepal’s 130,000 drug users. That figure rises about 5 percent annually, thanks in part to increased opium cultivation under Afghanistan’s resurgent Taliban regime, and the arrival of synthetics like fentanyl from China and India. Though tourism is a saving grace for trekking hot spots and Kathmandu, precious few foreigners visit interior cities like Butwal.

Many leave altogether. Last year, with the COVID-19 pandemic having devastated industries across the nation, more than 400,000 Nepalis sought work in the Persian Gulf—most on the infrastructure of Qatar’s controversial World Cup. Thousands have returned in caskets. Politicians and activists have therefore framed the issue of cannabis legalization as not just a matter of personal and economic freedoms, but as a form of protection against overdose deaths and mass exodus. Mina Tamang, a representative in the Maoist Centre Party, told me that the negative perceptions of cannabis that persisted after the Seventies have now softened. Legalizing the drug, she said, “opens up opportunities for the development of a new industry, including cultivation, production, and export of cannabis-related products.” The former health minister Birodh Khatiwada, one of Nepal’s loudest voices for reform, told me that legalization would reverse “the trend of people going outside the country.” Many of Madan’s social-media followers are based abroad, he told me. “They say, ‘Please Bhai . . . we will come back if marijuana will be legal. We will grow, we will save—the money is in our land.’ ”

The morning after we arrived in Butwal, we were joined by a rawboned and bearded man who went by the moniker “Honest Lier [sic]” and shifted nervously in the back seat. He would chaperone us to Thawang, the reputation of which instills fear in Nepalis to this day, and introduce us to a local veteran of the Maoist insurgency. But after a couple of hours on the road, the vet called to tell us that he, too, was doing construction work in Dubai. “He’s from a place where money grows on trees,” Honest Lier clucked, tucking the paper of a blunt with his long, brown-stained pinky nail. “And he still has to do this stuff. We’re sleeping on a golden pillow. But the system won’t let us wake up out of this bad dream.”

Thawang is some seventy miles northwest of Butwal. Pavement quickly turns to gravel there, and by lunchtime on our second day the Mahindra was inching at a mule’s pace through the canopy of the Annapurna Conservation Area, a giddy collage of dogwood, dhupi, and pine—whose puffy pompom clusters blotted the forest like raindrops on a watercolor. Behind them the massif rose and fell like gigantic shark teeth.

As the sun fell and we descended into Rolpa, Dipesh switched the stereo from metal to reggae, lit what I reckoned to be his tenth joint of the day, and spoke of the profound joy he drew from playing a role, however small, in Nepal’s cannabis comeback. Madan posted hourly to social media, and got us to stop whenever he spotted what he thought might be cannabis growing along the road. When Honest Lier wasn’t rolling joints, he sat in silence—suffering, I would later learn, from terrible withdrawal.

It was dusk when we reached Liwang, a clutch of bright homes at the foot of a valley, and Rolpa’s district headquarters. Shadows drew barcodes across its central cricket field, and kerosene lamps lit the interiors of stores and homes like Dutch Golden Age paintings. It was becoming clear that we would have to reach Thawang in the dark, and nobody was quite sure how: roads in and out were impassable during the rainy season, and monsoons had half-submerged far more developed towns along the way. As Dipesh and Honest Lier plotted a route around a nearby mountain, Madan alerted me to a white high-rise. It was there, two decades earlier, he told me, that he had gotten his life back on track.

While he drowned in grief, drugs had been Madan’s only respite. Once he got to Delhi he could breathe. The Sahara Centre for Residential Care and Rehabilitation was a cramped, two-story block specializing in HIV and AIDS care for drug addicts. Working there gave Madan purpose, and he’d learned enough Hindi from Bollywood films to get by. His heart broke for the patients people would rather forget existed—he worked particularly with transgender residents, almost all of whom were dying as a result of unprotected sex work. “They were hated,” he told me. “And the HIV/AIDS just added to their pain.”

Madan knew that he had the virus even before a test confirmed it—but rather than flooring him, the twelve-month prognosis that followed gave him a renewed appreciation for life. “When I opened my eyes every morning, I thought, Thank God I’m alive,” he told me. “I live for today.” He resolved to stop using. Meanwhile, his mother’s health was declining. She begged him almost daily to return to Nepal. “I’m single, son,” she pleaded. “Come back.” One night in October 2003, Madan received the call he’d dreaded for months: Jhula had drunk herself to death, alone, in Inaruwa. His heart sank. “She became alcoholic due to anxiety,” he told me. “This was mainly because of me and her husband.”

Madan returned to Nepal, in 2004, to work at a Biratnagar hospice. There he saw firsthand how cannabis could ease pain. He didn’t care that the drug was illegal, and picked it up from dealers before dishing it out to residents as a self-styled weed wallah. Sometimes they were so consumed by relief that they hugged him. But he himself still struggled with mood swings. One day he fell into a rage and struck his boss. The head office called him to Kathmandu. “I want to work for HIV-positive people,” he begged them. “Anywhere in Nepal, I’ll work.”

They dispatched Madan on the long, winding road to Rolpa, where he would open new hospice branches, first in Liwang, then in smaller, more remote towns, including Thawang, a knot of homes in the gut of a narrow valley. The civil war still raged, and Thawang was encircled by roadblocks. But it was as close to a beyul as anything he’d seen, green and temperate, enveloped each night by fog that burned off the next morning like a natural hydroponics laboratory. Cannabis grew wild everywhere, and everybody used it—to cook, to knit clothing, to feed crying babies, to soothe sick cattle. Madan dove into online forums on strains and effects and growing techniques, and learned that, for centuries, it had been completely legal.

The war ended in 2006. In 2008, Nepal abolished its monarchy and went to the polls. Prachanda, under his real name, Pushpa Kamal Dahal, dissolved his eight-thousand-strong Maoist army and became the republic’s prime minister. Soon afterward, Madan returned to Biratnagar from his Rolpa expedition and met a woman named Tulsi, who remembered him from his childhood visits to the town. She was struck by his kindness, and they fell in love, marrying a month later.

In 2012, Tulsi gave birth to a son, whom the couple named Jesus. It made sense, given his own biblical nickname, and besides, more than a decade after Madan was supposed to die, the boy felt like a miracle. He soon injected heroin for the last time. “I had to look after my wife and child,” he told me. A week without the drug became a month, then two, then a whole year. Sobriety felt intoxicating. “Now without taking drugs,” he told me, “I feel like I am.”

By 10 pm on the second day of our journey, the Mahindra’s progress had slowed to a near stop along narrow, mud-logged passes. Rolpa’s fog had closed in; it felt as if we had slipped into a parallel dimension. We were beginning to contemplate sleeping on the SUV’s leather seats when Dipesh spotted lights in the distance. An hour later, we arrived at a small, half-built guesthouse on the edge of Thawang. We dumped our bags and fell asleep. The next morning, Madan promised me, we’d meet the people whose lives had been turned upside down by the war on drugs.

Portraits of communist leaders adorn a house in Thawang © Moises Saman/Magnum Photos

A shepherd near Thawang © Moises Saman/Magnum Photos

When Jaya Prakash Roka was growing up in the Seventies, cannabis was more valuable than cash. His family farmed other staples like corn and cowgrass, but cannabis—which grew wild on the edge of their Thawang plot—could feed, clothe, and heat their traditional wooden home, one of twenty-one in the village.

Even when Birendra banned the plant, and cops tore through town burning it, enough remained for the villagers to use, or to sell to black marketers for a tidy profit. It didn’t last long. By the early Eighties, Nepal’s economy had almost collapsed, and youngsters fled Thawang in search of work. Jaya Prakash had learned about communism as a teenager, as Maoists preached taking back control of the nation. In 1989, he became a community organizer.

“Maoism was for treating all people equally; taking care of the people,” Jaya Prakash told me when we met on the third day of the trip. He is short and slender, with tousled black hair and calloused hands. He lives in a tarp-covered one-room hut on a half-acre plot in the middle of Thawang, beside a stone-walled school, and surrounded by sweet-smelling, eight-foot-high cannabis plants with furry, pinkish buds (they used to be purple, he said, but climate change is making Thawang hotter, drying its soil and thinning its quantity of anthocyanins).

By 1996, when war broke out, almost everybody in Thawang supported the rebels. They would even sell cannabis plants to buy weapons in India. In response, Nepalese troops and police bombarded Thawang and carried out regular raids. Residents who were thought to be Chinese—as Jaya Prakash was—were often selected for arrest or torture, suspected of honeycombing local populations. Each time townsfolk heard distant gunfire they fled into the jungle, cowering in caves sometimes as long as a fortnight with little to eat, shaken by the American-made bombs. During one assault in 1997, Jaya Prakash’s wife had an asthma attack. The firefights prevented anyone from getting help, and she suffocated.

Jaya Prakash remarried months later, as the violence continued to grow. On April 10, 2002, around 1 pm, cops came searching for him. Along with his wife and three children, Jaya Prakash escaped to the hills once more, but the cops set fire to his home. Soon the entire village was ablaze. “Nothing was saved,” he told me. “Only ashes.”

After the blaze, Thawang’s inhabitants formed a commune of thirty-three families—the same number of locals who’d died in the conflict—and rebuilt some of the homes. But they didn’t include Jaya Prakash’s, and he has lived in the hut ever since. Both of his daughters live nearby, and his son is hoping to work abroad. Buses to Liwang cost $8.75—far more than he can afford—and public services have crumbled. He and his neighbors still roll charas at the end of each rainy season and sell it illegally, but if the cops find out, they’ll shake them down for cash. Refusal could mean a trip to jail, adding them to the thousands of Nepalis detained on drug charges each year.

Prachanda “deceived people like us,” Jaya Prakash told me, waving a fist-size sickle from side to side. “He became a billionaire overnight. But he destroyed the future of Nepali people. Many joined the war hoping for a better future, leaving children and parents at home, their fertile fields remaining barren for years.”

Today he feels as if communism was little more than a giant romance scam. “It’s painful to see all this before my eyes,” he said. “Prachanda destroyed everyone’s future in our village. For us he’s public enemy number one.”

As we spoke, Madan chewed and spat out ever greater quantities of gutka. “Poor people don’t have any choice,” he told me. India’s economy has boomed in recent years, accompanied by an increasing demand for drugs. Local crime bosses may give growers and mules anywhere from $75 to $90 to smuggle charas into India. But if they’re caught, he said, “the kingpins won’t be mentioned.”

Madan has collected signatures from more than a million compatriots in favor of legalization, many from poor, rural communities like Thawang—a “grassroots campaign,” he likes to joke. In 2007, he met a fellow recovering addict and HIV/AIDS advocate named Rajiv Kafle, and the pair struck up an unorthodox friendship. Madan is bombastic and brash, while Kafle is reserved, almost bookish. They submitted a private bill, which 54 of Nepal’s 275 members of parliament endorsed. In March 2020, then-minister Khatiwada led the charge to end Birendra’s ban, and later that year Nepal backed a successful U.N. vote to remove cannabis from its list of the world’s most harmful drugs. As the movement grew, Madan and Kafle appeared on news stations, built a digital presence, and protested—all the better if the cops threw them in jail. Their slogan was always the same: Jai Dess, Jai Charas—Victory to the country, Victory to hash!

A jungle northeast of Kathmandu © Finn Kassell Osborne

Fearful of repeating the previous night’s ordeal, we left Thawang before lunch, collecting plants to add to the growing portfolio Madan cultivates on a small farm outside Kathmandu. By midafternoon, the Mahindra was running out of gas, with stinking cannabis plants hanging out the windows like a prop in some postapocalyptic zombie movie.

While we were parked in a village, two cops spotted our stash and escorted us to a station in the nearby city of Baglung. Officers crowded the vehicle, sniffing and remarking on the high quality of the plants. One even told Madan he wanted to visit Thawang when the ban was lifted, before sending us on our way with the majority of the buds pruned and gathered up in tote bags. Madan had produced a document claiming the right to research new strains—he wouldn’t tell me its provenance—and that seemed to do the trick. “I wasn’t scared,” Dipesh told me later. “Jail? So what! I believe in this guy.”

I left the trio that evening, and reached Kathmandu a couple of days later. I wanted to explore Freak Street, but today it is little more than a browbeaten alley of bars, fast-food outlets, and souvenir shops. Most seemed to close by 9 pm. Legal weed might lure the hippies back—or at least their grandchildren. Caribbean nations now offer cannabis tours, and Thailand has legalized its own storied recreational market. Getting high in the Himalayas would seem to be an attractive draw. “The consumer is becoming more mature and more knowledgeable,” the cannabis marketing professional Ben Hartman told me. “Maybe hash and temple balls would be new to Americans. Maybe it could work.”

Birendra’s ban destroyed centuries-old cultivars, and plants grown artisinally by the likes of Jaya Prakash pale in strength compared with those offered by established American and European firms, some of which now grow weed with THC levels upwards of a mind-bending 30 percent. Most Nepalese hash tops out at 17 percent. A safer bet would be to focus on the lower-grade medicinal market, which is expected to be worth almost $60 billion in just five years. Nepal’s natural environment may allow it to compete with much richer states, or to entice foreign corporations to invest.

Many locals believe that foreigners have long enjoyed the best of Nepal’s immense natural wealth, whether that’s climbers scaling its gigantic peaks, companies employing its youth, or hippies consuming its most potent charas. Legalizing weed may help reverse the trend. But, in an ironic twist, the same nations that pressured Birendra to ban cannabis are now legalizing it en masse, beating Nepal to the punch. “The wound goes deeper when nobody even recognizes that you’ve been shafted,” Dixit, the publisher, told me. “Nepal continues to suffer—and hence the poorest of Nepal continue to suffer—while in the West everywhere there is now a movement toward legalization.”

In May, Nepal’s government agreed to carry out a feasibility study regarding medical marijuana farming. Whether Nepal will build an equitable industry and give its farmers back their cash crop depends on its politicians. Kathmandu could choose to issue a handful of licenses, as the Netherlands and Germany have done, handing Nepal’s cannabis market to a cartel of high-bidders. Or it could adopt an “immaculate conception” model, like Thailand, granting illegal producers a no-questions-asked ticket into the legal market. The latter model might receive “a lot of pushback,” the cannabis-policy attorney Jason Adelstone told me, “because people say that’s how you get a lot of diversions and black markets. But it’s also how you get small communities involved in a state-regulated program.”

Madan believes there is room in this future Nepal for his own cannabis empire. In 2009, he moved from Biratnagar to Kathmandu and rented a one-third-acre strip of land just outside the city, telling its owner he wanted to raise chickens and cattle. Within two years, using knowledge he’d picked up in Rolpa, the tiny farm—which is guarded by a little white dog named Gorey—began producing thick, emerald-green plants, which he harvested and stored in his fridge before selling them across the city. Today he makes around $350 per month from seeds and plants he packages in yellow-and-green spice jars. He asks each prospective buyer to tell him why they want the drug: whether they want energizing sativa buds or relaxing indica, and whether they are in pain. When the drug is legal, he told me, he will construct a remote jungle hacienda to splice new strains and—if he lives long enough—retire.

That would be the ultimate gift he could give his son, he said, providing a stability he never had. During our time together, Madan swung between attributing his ambition to his father’s death and denying he owed anything to the man at all—a tug-of-war that I imagine most children would find familiar. Madan’s parents were deeply religious, yet he “never honestly saw God.” He hasn’t conferred any faith upon Jesus, his son, telling him, “I am your God. Your mother? She’s your God. Praise us.”

When I visited Madan in his apartment, he told me that he speaks to each plant like a family member. He credits the drug, at least partially, with his sobriety—and he only smokes it when he gets sick. I envy his optimism. But I also fear for his business prospects in a market regulated by politicians who have presided over one of the world’s most rapidly widening income divides. Meanwhile, prohibition still bites back. Last summer, for example, cops spotted the farm and, despite Gorey’s vigil, cut down around a quarter of the plants.

On one of my final days in Nepal, Dipesh drove me, Madan, and Jesus up through the sinuous trails of Kathmandu’s surrounding valley to a drug-addiction refuge called Hippie Hill, which Madan and Kafle founded soon after they met. Its concrete walls are covered in graffiti honoring Hindu gods, the hippie trail, and, curiously, Steve Jobs. Young men sat on second-hand couches doomscrolling to a soundtrack of local rap. As night fell, the city below shimmered like the flank of some huge, bioluminescent creature. Cannabis plants swayed in a series of terraced gardens. Dipesh brought fried chicken and lit a joint. I had spent the previous few hours grilling Madan about margins, models, licenses, and competition, wondering whether our journey to Rolpa, and the days that followed, were attempts to ennoble what is essentially a modest weed dealership. But hearing him speak at the refuge, looking out over the homes below, I realized that it wasn’t an act. Was he starry-eyed? Sure. But cannabis had, in a way, saved his life—and growing it was his own kind of heaven. “This place is like a temple for me,” Madan said as he held his son. Then, gesturing to the cannabis around us, he added, “Here is the black gold, which gives you peace. That’s why everybody came to Nepal.” Cops, politicians, investors, he told me, “only see plants. I see life.”