Illustrations by Patrik Svensson

The Year of the Rabbit

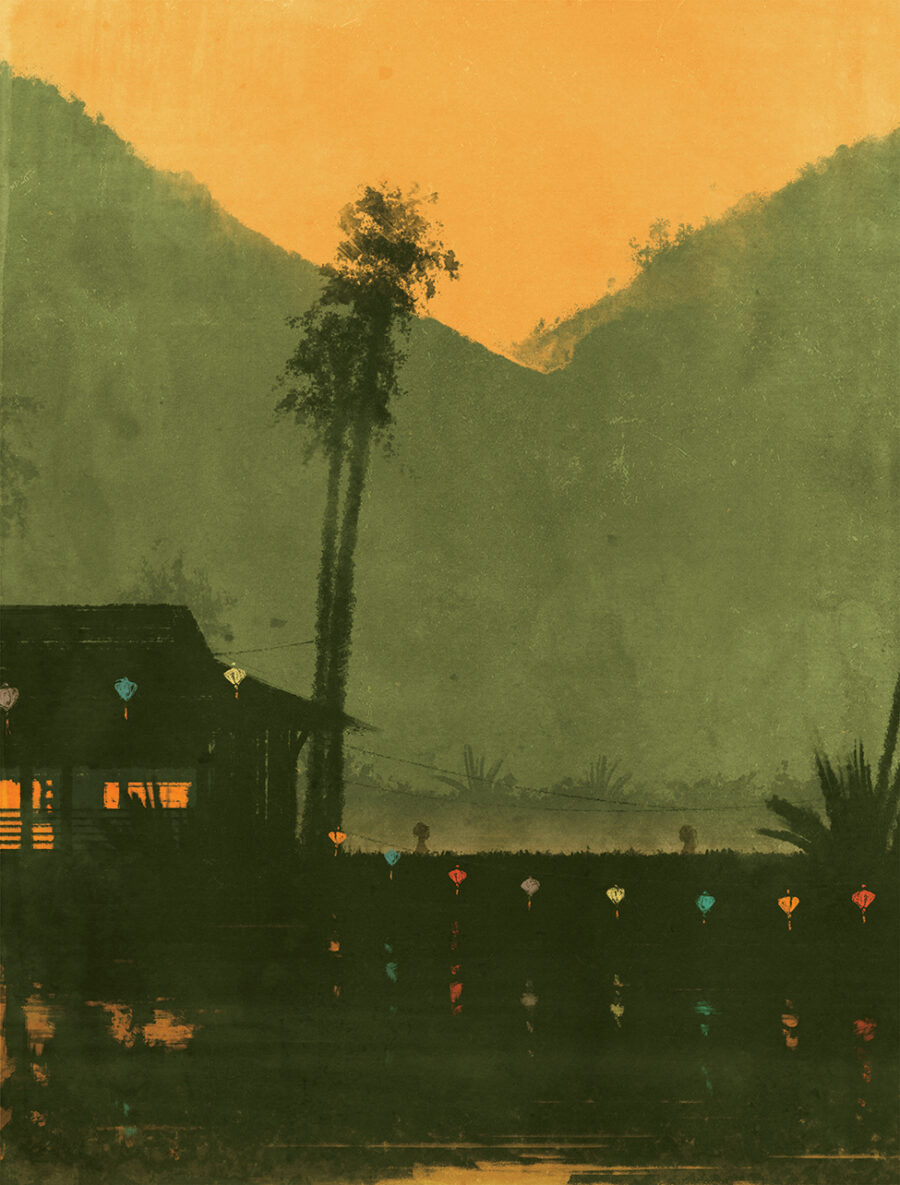

I’m going to take a minute now to see if I can get my dates straight. Peter and I were married in June 1962. In early December, Peter told me we were going to Saigon. We left for the West Coast in February 1963, and arrived in Saigon right after Tet.

I recall how disappointed I had been that morning to find I was not yet pregnant. Another month before I began to hope. A few more weeks, then, when I dared say a word to Peter. My first doctor’s appointment was in May, after my second missed period—a doctor at the Navy clinic most of the female dependents used. Peter ha d gotten his name. I was too superstitious to ask any of the women I knew for recommendations. Not yet.

The doctor assured me we’d hit the mark. “The rabbit died,” is what we said in those days, although I don’t think any rabbits were actually involved. It was, the doctor pointed out, the year of the rabbit. A good omen, he said. And I recall Peter asking later, “How is a dead rabbit a good omen?” We had a laugh over that.

Peter’s assignment was meant to be for nine months to a year, so chances were good I’d be home for the delivery, but Dr. Navy (cannot recall his name, no doubt I’ve suppressed it) said he was perfectly capable of delivering our child for us should our plans change. And, he added, nursemaids were so cheap over here, why go back to the States where you’ll have to do all the care and feeding yourself?

And think of it, he added, all his life your baby will have an intriguing tale to tell about the exotic place where he was born. All his girlfriends will be checking their atlases.

I had the sense that he’d said this to other women, that it was one of his standard, avuncular attempts at a charming bedside manner, but still the words gave me, for the first time, permission to exhale, to begin to imagine our child’s long life.

Early June and I was dressing for another party. A reception at the American Embassy, then dinner with three other couples at My Canh, a floating restaurant on the river. A popular place for families. Maybe because it was a popular place for families, it was bombed by the Viet Cong only a few years later. There was a photograph, as I recall, not as well-known as the little girl fleeing the napalm, but the kind that sears your memory nevertheless: an impossibly bloodied child—impossible because her body was so small—in the arms of an American man—the eyes of both, man and child, blank, somehow, utterly expressionless. Shock, I suppose. You can only imagine what those eyes had seen.

But that was some time later, as I said.

We were still keeping the news of my pregnancy to ourselves, but I was sure knowing glances would be exchanged among the other women when I refused a cocktail. I recall I’d just had a new dress delivered from Maison Rouge. A silk floral with a full skirt. I was looking forward to wearing it, wondered how long before I outgrew the fitted waist.

I was in the bathroom just off the master. It was a fairly large Western-style bathroom with a lovely soaking tub. I was in my slip, waiting until the last minute to put on my new dress. A sudden sense of vertigo, and then a small cramp. Nothing dramatic. No more than the bottoming-out sensation of an elevator dip, followed by a brief stab, like a runner’s stitch, in my center. Followed immediately by an utter sense of devastation: the collapse of something precious and irreplaceable, that gale of disbelief that follows the news of any loss, that follows the sudden, slipped-from-your-fingers loss of something invaluable.

But that was brief as well. I shook it off, finished doing my makeup. Sprayed my hair. Used the toilet one more time and saw the spot of blood.

It seems strange to say now, it even seemed strange to me at the time, but my first thought was that I did not want to be the sort of woman who had a miscarriage. Didn’t want to be a part of that simpering sorority, a keeper of that shameful secret (for so it was considered at the time), that failure. Until that moment, I was on the side of healthy, fertile women who gave birth easily to robust and beautiful children.

Now, with the small circle of blood, I was on the side of the stumblers, the weak, those sick, troublesome, bedridden women in pin curls and satin bed jackets who gave their long-suffering husbands nothing but grief and disappointment.

I wanted to put on the new dress, pretend this wasn’t happening, carry on regardless, but I had a vision of blood staining the seat of my skirt, soaking through the gorgeous silk while solicitous but subtly scornful women came to my aid with linen napkins sympathetically placed.

When Peter called to me from downstairs to say we were really running late, I asked him to come up. His particular expression of husbandly indulgence and impatience—he was, I could tell, prepared to tell me I looked fine, any dress was as good as another, we’re late—fell away as soon as he saw me, now in my dressing gown, stretched out on our bed.

“What’s wrong?”

I said I’d had a wave of nausea. Said perhaps the morning sickness I had so far avoided had finally found me here in the late afternoon—maybe it was confused by the time zone.

He took my hand. Said we’d cancel our plans.

But I told him to go. Told him I only wanted to sleep and he’d be here all night with nothing to do. We’d already sent the cook and the yard boy home, as we usually did on the nights we dined out, and Minh-Linh, our housekeeper, would return to her quarters out back as soon as she’d prepared our bedroom for the night.

I told Peter to ask her to stay, maybe she could bring up some tea once I’d had a snooze. I remember he was wearing a new suit—I’d gotten the name of the tailor from Helen Bickford, whose husband was always impeccably dressed. He was freshly shaven, I could smell his signature bay rum. Behind it, a touch of the gin and tonic he always had as he waited for me to get ready. He seemed so boyish sitting on the side of the bed like that, and I was so in love with him that I whispered, without thinking, “I’ve had a little blood.” And then wished I hadn’t.

He flushed. “Is that bad?’ he asked.

“Not really,” I said, with an authority I completely lacked. “It happens.”

I saw him glance, surreptitiously, from my face to my breasts, hips, legs. And then he quickly looked back again, as if everything below my neck—that territory he had so expertly explored over these many months—had suddenly become alien to him, somewhat disconcerting.

We came up with a compromise: he would go to the cocktail gathering, then come back to see how I was doing. We would decide then whether or not we would go out to dinner.

I suppose I slept heavily for a while. When I woke—the cramps were now full-blown menstrual style—the lights in the room had been lowered, the air conditioner was humming, and a joss stick burned on the dresser. I went to the bathroom, more blood, but nothing copious, and when I crawled back into bed Minh-Linh appeared with a tray: a teapot, a delicate cup and saucer, a plate of rice crackers.

I hadn’t known until that moment that she knew I was expecting.

She was middle-aged, thin, with a quiet industriousness about her. She looked humorless on first encounter, but we’d quickly learned that she laughed easily. Peter claimed that she understood English very well and was also fluent in French, but I hadn’t had much occasion to speak with her at length. She’d been taking care of whoever occupied this house for years, and my impulse had always been to accede to what I thought must have been her well-established routine.

She placed the tray on my bedside table and poured a cup. I sat up to take it from her. Then she went to the window to turn off the air conditioner, and then turned on the overhead fan. She knew this was how I preferred the room when I napped. She came back to the bed and asked, “Feeling better?” I only shrugged, too exhausted and worried to be perky. She patted her flat stomach.

“Much pain?” she asked.

I nodded. And then raised the teacup to my lips to keep from blubbering. But the tears came anyway.

Gently, she took the cup from me. She ran a comforting hand over my hair, still stiff with going-out hair spray. I suppose it felt odd to her. She went into the bathroom and found my brush. Then she nodded that I should move over. She sat beside me and slowly brushed my hair until the hair spray was combed out and I’d cried all I could cry. And then she gently pulled my hair back over my ears and braided it neatly. When she was finished, she returned the cup to me. I drank the now tepid tea, ate a tasteless cracker. She fixed the pillows behind me and said, “Sleep, please.”

As I slept again, I imagined that my sincere affection for Minh-Linh was surely purer, less condescending, less self-satisfied, less colonial, certainly, than that of the other female dependents for their housekeepers here in Saigon. Another kind of American hubris, I suppose.

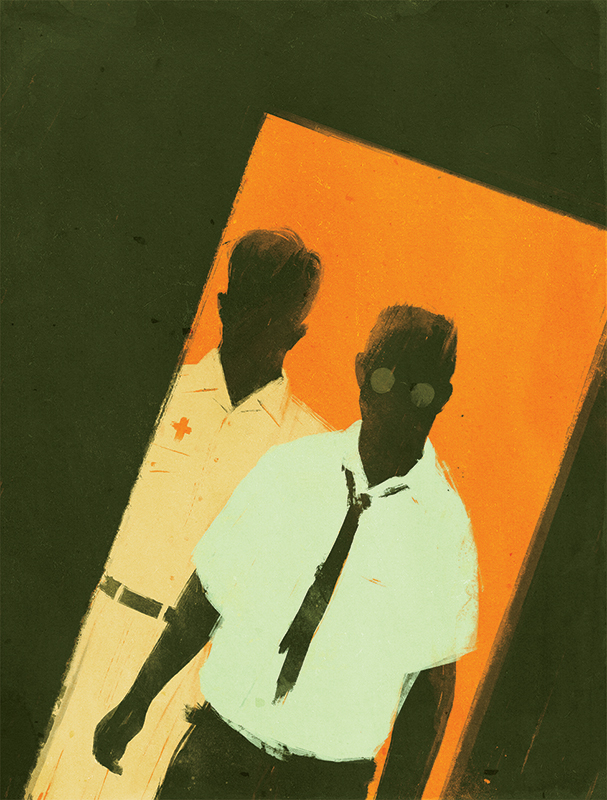

I woke when Peter came in, my Navy doctor just behind him. They both had their jackets off. Peter wore a white short-sleeved dress shirt, his collar open and his tie unknotted. The doctor was in his military beige. They both filled the room with the smell of cigarette smoke and sweat.

Peter said, cautiously, “How are you feeling, honey?” He stood at the foot of the bed. He seemed a little shy, maybe embarrassed, and I suddenly touched my hair—Minh-Linh’s French braid coming undone. Not a look he was accustomed to. I suppose it made me look weaker than I felt. I struggled to sit up. I knew I was bleeding heavily now.

Dr. Navy moved into our bedroom with more authority than my husband had, tossing his jacket on the bed, coming toward me as if to make some small adjustment to my head and neck that would restore proper order. He felt my forehead. His hand was large and soft, the backs of his fingers covered with manly fur. I felt a rough callous or two. A golfer or tennis player, I thought. He wore a handsome wristwatch.

“No fever,” he said, and then sat heavily on the side of the bed. “Any pain?” he asked.

Reluctantly, I told him I was a little uncomfortable. Not much.

“You can take some aspirin,” he said. “It won’t hurt the baby.”

I knew he was drunk. I could see how he struggled to keep his eyes properly focused, and yet his words filled me with hope. If he believed the baby would not be harmed by an aspirin, then he believed the baby was still there, still headed for his birth in this exotic place.

“There was some blood,” I whispered, and glanced at Peter, who glanced away.

“It happens,” the doctor said. “My wife was always springing leaks when she was expecting—we’ve got five.”

He showed me his palm, fingers spread and wiggling, as if to illustrate five plump children with hair on their backs.

“Nothing unusual. You first-timers fret about everything.”

He patted my thigh. “Get yourself some rest, little mother,” he said. “Take an aspirin if the pain gets bad.” He gestured toward Peter. “I’m going to take this man of yours out for a good meal. Things will look better in the morning.”

Peter asked, “Do you want me to stay?”

I waved him on. He’d probably had a few too many himself. “No, go,” I said.

In truth, I wanted them both gone so I could get to the bathroom and see the extent of the blood. I wanted to take that little bit of assurance this drunken doctor had given me and hold it up against the fact of whatever it was my body was determined to do.

They lingered a bit longer. Discussed bringing something back for me to eat, some soup or some pho. Peter told me he had already asked Minh-Linh to stay close. She’d spend the night in the second bedroom. She’d offered to cook some eggs.

I said, perhaps impatiently, that I was fine. Rest was what I needed.

“Absolutely,” the Navy doctor said. “R and R. The best medicine.”

As they left the room, my husband asked the good doctor, “Is that a Rolex?”

I waited until I heard them go out through the gate, until I heard the car—it might have been waiting—take them away.

In the bathroom, I saw the blood was copious. And then I saw, in the midst of it, the small sac of the embryo. I reached into the toilet, into the water and the blood, and scooped the tiny thing out. Held it in my cupped hands. It was so small, but still I recognized the pale seahorse shape from college biology textbooks. The curve of it, the dark indication of an eye. I slid it from my palm to a folded towel on the side of the sink, washed the blood from my hands, changed into another nightgown, and went back to bed.

So now I was a woman who had had a miscarriage. So now we would begin again, the monthly hope and disappointment, now with a little more caution, a little more fear. Now the easy, fertile future—my part in our successful life together—was no longer so easy. Or so assuredly mine.

I heard from downstairs the buzzer at our gate. Heard Minh-Linh go out. Heard her voice as she returned, intertwined with—I felt another elevator drop—Charlene’s. I heard Charlene come up the stairs.

She wore a sleeveless cocktail dress of deep-green shantung, with a slim skirt, a V-neck in front, and a raised collar in the back, regal. Her hair was up in a French twist, her diamond earrings sparkled. Her hazel eyes appeared green. She really was, in that dim light, remarkably attractive. Some cross between Grace Kelly and Maleficent.

I was braced for her reflexive sneeze of a laugh, but all she said as she came into the dim room was “kiddo.” It was neither maternal nor condescending. It was—for lack of a better word—businesslike, efficient, authoritative even. Queenly. “What’s going on?”

I told her, without weeping, that I had miscarried. That I’d been almost three months along.

She said, “Shit.”

In those days, I was not—I dare say most of us were not—accustomed to hearing women like Charlene curse like that. It startled me, but also made me want to laugh.

She frowned. “You’re sure?”

I nodded toward the bathroom and she went right in—she was wearing strappy black heels—businesslike, as I said. When she returned, she had the towel that held the embryo folded in her hands. She sat beside me on the bed. I sat up, leaned forward. With hardly a thought, hardly a doubt, I put my cheek to her tanned and freckled arm, which was surprisingly cool. There was the metallic tang of perspiration just beneath her lovely perfume.

Charlene placed the towel on her lap, over the gorgeous green silk, and unwrapped the little thing, barely distinguishable now against the blood-soaked cloth. We looked at it together, silently, for what seemed a long while. I was aware of the click of the fan above our heads, the encroaching heat, some distant sound of traffic and voices in the street, Charlene’s flesh against my own. The joss stick had nearly burned down, but the scent of it was still in the air.

And I suppose it was this scent that made me aware of both how far from home I was, how strange this place was, and yet how confined and familiar everything now felt, as if, with my own small failure, my own small grief, the world had shrunk, distance had lost its meaning. Nothing was foreign. No one was a stranger.

I mean, here was Charlene, beside me in my own bedroom, my cheek to her bare arm.

Gently, she placed the towel in my hands. She reached for the half bottle of Vichy water on my bedside table and poured a drop into her palm. She wet the fingertips of her right hand and made the sign of the cross over the tiny thing. Softly, she said, “I baptize thee, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.”

Then she bent her head and whispered an Our Father. I joined her, pausing awkwardly as she spoke the final, Protestants-only (as I thought of it) phrase, “For Thine is the Kingdom, and the Power, and the Glory, forever and ever.”

They seemed very grand words for such a small gathering of cells.

She took the towel from me, folded it over again.

“What should I do?” I asked her, not wanting to say, “What should I do with it?” But I knew she knew this was what I meant.

Charlene said, “Let’s think for a minute.”

She carried the towel back into the bathroom, rested it again on the edge of the sink.

When she returned, she emptied the bottle of water into a glass. Then went to her purse and found a small prescription box. She slid it open and shook out a pill, which she handed to me, with the water.

“You might as well,” she said when I hesitated.

I swallowed the Librium and some water. She seemed satisfied. Took the glass from me and then bent down to whisper in my ear.

“I hate this,” she said, hissing the words. “I just hate it.”

There was a small bamboo chair in the corner of the room, and she carried it one-handed over to the side of the bed. She sat down, kicked off her heels, rubbed her stockinged toes. Casually, casually gossiping, she mentioned who had been at the party that night. The usual suspects, she said. I think it was at this time that the American ambassador was off to the Aegean on a family vacation and the deputy chief of mission was acting ambassador. Charlene couldn’t say his name, Trueheart, without some venomous irony coloring her voice. “Like something out of Ivanhoe,” she said.

The gossip in those days was about a new ambassador—there was an American delegation in town, perhaps related to this. I remember Charlene telling me that they couldn’t stop perspiring.

What else did she say during that long night? I recall how she leaned across her lap and spoke in the tone you might use (I myself had used it) to distract a small child from a chicken pox itch, a scraped knee, a fever. She’d caught a glimpse of Madame Nhu somewhere: beautiful, tiny. Maybe a bit heavy-handed with the eyebrow pencil.

“The Dragon Lady,” I said, to show I was grateful for her efforts to distract.

Charlene gave me her cool, assessing green eyes. “Don’t fall for it,” she said. “She’s a woman with spunk. Which is why men want to hate her.”

She went on: a higher-up at one of the U.S. agencies—USIS, USOM, I can’t recall—had been at the party with his unhappy wife. Apparently, he’d been off in the countryside for six weeks, something to do with the rural hamlet program, and the wife had been left alone in Saigon.

Charlene insisted I’d met the woman somewhere—she’d introduced us, she was certain. “She’s a clotheshorse,” Charlene offered. “Tonight she was wearing Guy Laroche, two pieces, coral-pink. Would have been lovely if it fit her right.” She shook her head—what to do with these women?

“Girl spends a fortune on clothes,” Charlene said. “But not successfully. It’s all higgledy-piggledy. She doesn’t want the clothes. She just wants her husband to pay for them.”

At one point during the party, Charlene said, this woman’s husband took her elbow to turn her toward an introduction, and “the poor girl” pulled away from him as if she’d been scorched. He cursed her under his breath. Everyone heard it. Everyone saw it. Awkward for all.

And Helen Bickford had a tale to share. Charlene leaned over her skirt. “This is just between us.” Apparently, Charlene said, Helen had a friend back home, who had a friend at the Pentagon, who was the friend of a woman there who projected the draft call numbers for the Joint Chiefs. Five years out.

“It’s quite complex,” Charlene said. “She takes all kinds of things into consideration. Retirements, reenlistments, men who’ll be drafted and then rejected, all overseas deployments, of course. And she needs to project five years out. Across all the services. She needs to be extremely accurate. It’s quite a job.”

I tried to attend. I know I asked, “A woman does this?” But as she spoke I was listening, too, for Peter’s return, hoping this time he would not bring the doctor with him. I was considering whether I should show him the little embryo. I decided no, I should not.

I was thinking of how naïve we had been, he and I, over these many months, believing that all our fun, our passion and delight, would lead only—joy upon joy—to a healthy child in our arms, our own.

Charlene was saying that Helen Bickford told her tonight that last month this woman at the Pentagon was asked to go back and recalculate her projections for next year, 1964. This never happens, Helen said. These are careful numbers, carefully calculated five years out, there’s never a need to reassess. Pretty clear the order had to have come from the White House.

This friend told Helen Bickford that this woman at the Pentagon was ordered to recalculate next year’s draft projections based on a full withdrawal from Vietnam. Everyone. All the brass, all the GIs, pilots, MPs—all. All out of here by the end of next year.

“Picking up our marbles and going home,” Charlene said. “Not just the troop reduction JFK’s been talking about. Total withdrawal.”

I moved uncomfortably in the bed; a cramp was cresting.

“What about the communists?” I asked, hoping to prove I was listening.

Charlene stood, walked around the room until she found an ashtray. She took a cigarette from her purse. “What about the peasants?” she asked, lighting it. And then, with a laugh, “What about Brown & Root? What about Esso? What about the porcelain-faced Madame Nhu?”

She came back to the chair, shrugged, went on talking. She said she’d looked for me at the reception. Found Peter, who told her I was under the weather. And then, of course, she saw him leave with Dr. Navy.

“Don’t go back to that guy,” she said. “Next time around. The last thing you want is a Navy doctor. They hardly know what they’re looking at. They get your feet in those stirrups and their ears between your knees and suddenly it’s all Up Periscope. They spend the rest of the exam trying to figure out what’s port and what’s starboard. Wondering where the hell the penis is.”

I smiled. Still shocked, but growing less so, by Charlene’s language.

“I went to a Frenchman for little Roger. He’s had a practice here for years. All the elites see him. He came right to the house for the delivery. Kent wanted me to go to Hong Kong, but I wouldn’t hear of it. Leave the twins alone here?”

She brushed the suggestion away with a wave of her cigarette.

“Go to my guy. He’s getting on in years, but he has a deep and abiding love for women. It’s delightful. I’m thinking of getting pregnant again just to see his brown eyes above my belly. You’ll swoon.”

When Minh-Linh came in with her tray, more tea for us both, she asked me if I would like some eggs, and Charlene replied, “Good God, no.” Which was my sentiment exactly. I was happy to let her speak for me.

Minh-Linh poured the tea and handed us each a cup. I saw her glance into the bathroom; she seemed about to go in to tidy up when Charlene said something to her in quick French. Minh-Linh paused, then glanced at me. Then nodded. She said, softly, “I understand.”

She went out with her tray but returned later with another joss stick and what looked to me at first like a small gray stone. She lit the stick and placed it in the little sand-filled pail where we burned our incense. And then she placed the stone before it. It was in fact a small, smiling Buddha.

Sharp-eyed Charlene, smarter than everyone, said, “Jizo?” And Minh-Linh shook her head. “Dizang,” she whispered. Charlene nodded. “Very sweet,” she said. “Thank you.”

When Minh-Linh left again, Charlene looked at me and frowned. She did not like to be corrected. “Same difference,” she said. “It’s Jizo in Japan. Dizang here. A bodhisattva. Protector of travelers, but also of stillborn or miscarried children. Very sweet of her.”

She told me then that she and Kent were in Tokyo when she miscarried after the twins. A Japanese friend had given her a similar little statue. She was five months along.

“I’m sorry,” I said, but Charlene shrugged and sipped her tea.

“Poor little thing was a mess,” she said. “Hadn’t developed right at all. She looked like a glove turned inside out. A little monstrous.” She tossed off a small laugh. “Although I guess that’s true of us all. Inside out, we’re all monsters.”

I was strangely comforted by this news. I had not yet taken into consideration that there had been an imperfection in Charlene’s life.

“Apparently, Jizo, or Dizang,” she was saying, “watches out for the little souls that have not lived long enough to accumulate good deeds. Who can’t cross over into the spirit world—permanently neither here nor there. Left only to pile stones endlessly on the edge of the riverbank. Just this side of the River Styx, I guess you could say. What you Catholics call limbo. Not exactly purgatory because there’s no hope for change.”

“How sad,” I said.

Charlene squinted at me through the smoke. “It gets worse. It’s a limbo without mercy. Apparently, there are demons in this place, this place on the riverbank. I guess so the little ones don’t get deluded into thinking they’re in heaven. The demons torment these lost souls, scatter their piled stones. Jizo, Dizang, protects them, hides them under his robes. A hint of benevolence in a place of eternal stasis.”

She paused, picked some tobacco from her tongue. “Or some such,” she added. “As I understand it, Jizo is a bodhisattva rather than a Buddha because he’s elected to serve the underworld before reaching enlightenment himself. A kind of martyr, I guess. Assigned to the saddest and most futile of projects. Doing whatever good he can for these hopeless ones. What inconsequential good.”

I saw her rub her thumb and ring finger together under her cigarette. A sign, I was beginning to learn, of her own quick thoughts. “Or something like that,” she went on, suddenly dismissive. “Buddhism is charming but I can’t say I truly get it.”

“Minh-Linh’s a Catholic,” I told her.

Charlene shook her head. “So’s Madame Nhu. But she was a Buddhist first.” She squinted again. “Or maybe Minh-Linh finds it politically expedient these days to call herself a Catholic. With all that’s going on.”

I knew this was possible, but still I said, “I’ve seen her at Mass.”

Charlene laughed her laugh.

“Well then, you’ve been given your first little Buddha by a Roman Catholic.” And then she added, softening, “But that’s Vietnam. A mishmash.”

She stood, plucked the little figure from the dresser, and examined it carefully. Then she padded over in her stockinged feet and handed it to me. It was plump and sweet-faced, of course, smiling, eyes closed. The outlines of small children were carved shallowly into the stone hem of his robe. There was something comforting about the way this happy little bit of cool rock fit into my palm.

I hefted it and felt another wave of tears.

Charlene reached for her purse again, induced me to take another Librium with my tea. She took a few as well. Knocking them back with the dregs of hers.

At some point that night, our conversation led us to Charlene’s night terrors. They’d plagued her since the twins were born. Not nightmares, exactly, because she knew when they were happening that they weren’t dreams, and, moreover, she knew she was not asleep. And yet, she said, whenever she tried to explain them—to her husband, to the doctors he’d sent her to—she always reached first for some description of darkness. These terrors were, she said, infused with a terrible sense of waking darkness. Something like what the newly blind must feel. Or the newly buried. Impenetrable darkness with its attendant disorientation, missteps, clutches at the air. And yet there was also this tremendous certainty on her part that something truly worthy of her fear, something as solid as it was horrific, was there, in this darkness. Something terrible within it, or maybe just beyond it. It was not sleep, not dream, not nightmare, and she always felt afterward that if she had just managed to pursue it, terrified but resolved, she would have discovered a glitch in that dark veil, a tear in it. She would have glimpsed . . . she couldn’t say what.

“It sounds awful,” I told her. We were both speaking drowsily by now. The hour, I suppose, or the Librium.

“Yes,” Charlene said. “Absolutely awful.”

She was on the little chair beside my bed, one leg pulled up under the lovely green silk of her skirt, the other swinging childishly. She said she only sometimes cried out during these episodes. Mostly, she sat up suddenly in bed, or—and this disturbed poor Kent even more—quietly rose, eyes wide open but utterly without sight—and stood stiffly in the dark, or sometimes with a hand held out before her, barely breathing, although when he touched her, he said, he could feel her pulse racing in every part of her body. And when she woke, her heart, too, would be racing. She would have to struggle to catch her breath. Like a third-rate actress in a two-bit horror movie, she said.

“Our doctor at home prescribed the Librium. Recommended a psychiatrist. Anxiety, he says, something to do with childbirth. Although I suspect he told Kent I’m completely batty.” She paused. “I know it sounds ridiculous. No one likes waking up soaked in sweat. But I’m not sure I want to be rid of them. They’re telling me something. About myself, I suppose. Who I am. They’re telling me what my little old mind is capable of.”

And then she laughed.

“I’m not a fool,” she added, suddenly sober. “And I won’t be patronized.” She paused, looked into the air, but this time I knew her impatient, green-eyed appraisal was not directed at me. “I mean to see what I’m meant to see.”

“Like what?” I asked her. She ran her eyes over the four walls of our bedroom. There was a bright gecko in the shadowed far corner of the ceiling that suddenly scrambled away, as if her gaze pursued it.

“Demons,” she said. “Demons who want to topple the little stones I’m piling up here.”

“In Vietnam?” I asked. Her cool gaze fell on me again.

“In limbo,” she said.

Later, well before Peter came home from dinner—he was very drunk—we did something, Charlene and Minh-Linh and I, something I’ve never told anyone about. We took that bloody little embryo and slipped it into the emptied prescription box. Charlene cleared a space in the pail of sand on the dresser and placed the box there. We added a few tissues and some broken-up pieces of another joss stick. We said another prayer. I said a Hail Mary in English while Minh-Linh said the same in Vietnamese. (I recall glancing at Charlene, as if to say, See? She’s a Catholic.) Charlene knew the prayer, but only in French. Together, we lit the tiny pyre and watched it burn. The smell of sandalwood overtook the room, and the brief flare of the flame caught the sweet stone face of Dizang, protector of my little sufferer, companion of my brief and ill-formed hope of a child.