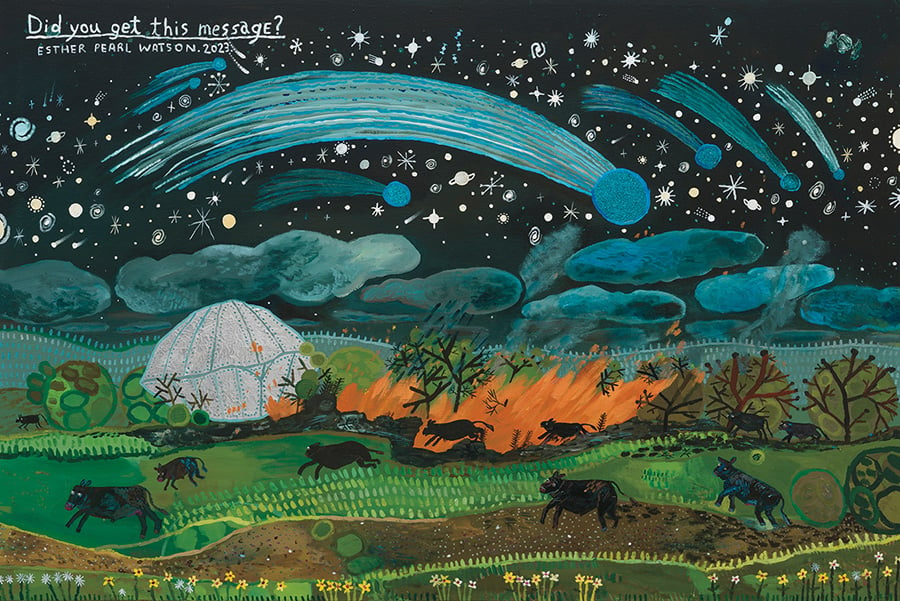

Did you get this message?, by Esther Pearl Watson © The artist. Courtesy Vielmetter Los Angeles

So you’ve seen a UFO—great! May I suggest keeping a lid on it? The past decade, with its hearings and headlines, has brought close encounter a new plausibility, but talking about aliens will still sully your reputation. No one is credible enough to deliver such earth-shattering news. This summer, David Grusch, a former U.S. intelligence official, told Congress and the media that the Pentagon had recovered materials of “exotic origin,” including “non-human biologics.” The Intercept promptly reported that Grusch was a suicidal alcoholic.

Carl Jung described UFO accounts as “visionary rumors” with the power of myth, which might explain why we vilify those who tell them: they resonate too strongly with our fears and desires. But today’s stories, with their cockpit footage and military hearsay, lack something of the flair of their Cold War predecessors. My favorite comes from Joe Simonton, a plumber in Eagle River, Wisconsin. In 1961, he claimed that a flying saucer resembling two “washbowls” facing each other had descended on his property piloted by several short men, “nice looking” and “swarthy, like Italians.” Their leader, his eyes “so penetrating” that Simonton had to look away, gestured for water. Simonton brought him some. Another spaceman was cooking something on “a square grill-like concern”: pancakes. “If that was their food, God help ’em, because I took a bite of one of ’em and it tasted like a piece of cardboard. And if that’s what they lived on, no wonder they’re small.” The spacemen gave him a stack, shut their hatch, and flew off in haste. “There I stood in the driveway,” Simonton said, “with a handful of greasy pancakes and my mouth open, wondering what the heck I’d saw.”

His was a vision of extraterrestrial life as commonplace as a roadside diner. I’m enchanted by the loping vernacular, the homespun loneliness, the griddle as an instrument of cosmic goodwill. “These men were friendly to me and I was friendly to them,” he said. He was strenuously honest—a county judge noted that he neither drank nor read science fiction—but reporters ridiculed him, strangers descended on his house, his business suffered, his chickens died, and he soon wished he’d kept the encounter to himself.

A few months later, a couple from New Hampshire reported having seen a cigar-shaped band of lights looming over Franconia Notch. Their announcement thrust them briefly into the gears of the military-industrial complex, which wrote them off as unreliable witnesses—a dismissal that altered the course of their lives. In The Abduction of Betty and Barney Hill: Alien Encounters, Civil Rights, and the New Age in America (Yale University Press, $30), Matthew Bowman, a professor of religion and history, argues that no UFO sighting happens in a vacuum. The Hills’ interpretation changed with the times. As optimistic New Deal liberals, they understood it to be a markedly different event than they would at the end of the decade, by which point they’d embraced New Age conspiracy and claimed to possess an arcane knowledge. Their evolving story allowed for “the rewriting of disempowerment into a strange new power,” Bowman writes. It reflected a burgeoning resentment of “the expert establishment” which is sustained in present strains of populism—and thereby suggests that the current wave of UFO interest is at root an expression of the vexed relationship between the state and its citizens.

The Hills’ account began simply. Driving home after midnight from a trip to Montreal, they spotted ominous lights flying toward them and pulled over to look at the object through binoculars. Spooked by its enormous size and oblong shape, they fled, hearing buzzing sounds “like someone had dropped a tuning fork.” “Do you believe in flying saucers now?” Betty asked Barney. “Of course not,” he said. At home, feeling “unclean,” they took long baths.

The Hills were government employees. She worked for the state welfare office, he for the post office. As devout Unitarians, they valued scientific expertise and open conversation. They were also, crucially, an interracial couple—Betty, white; Barney, black—active in the civil-rights movement. They saw themselves as people to be taken seriously. The sighting rattled them enough that Betty reported it to the Air Force. A man spoke to the couple over the phone, noting in his report that Barney “feels somewhat foolish—he just cannot believe that such a thing could or did happen.” Betty found the officer brusque. “The Air Force,” Bowman writes, wanted to use “the language and authority of science to defuse reports of unidentified flying objects before they turned into rumors that could stoke civic worry and unrest.”

Betty didn’t want to be defused. The event felt blindingly real. Barney was “driven to anxiety at his inability to understand what had happened to him.” The more they told their story, the more their memories perplexed them. Barney recalled having seen men on the ship scurrying in black uniforms with the “cold precision of German officers.” Betty thought the aliens handsome; Barney emphatically did not. He couldn’t remember how his shoes had gotten scuffed or why his wife’s dress was torn and stained with sweat. They kept returning to Franconia Notch for clues, “looking for the elusive moment their lives had changed.”

They found solace in UFO research groups, such as the National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena (NICAP), a non-profit that prided itself on its rational, technocratic approach. “We are mature people associated with a major electronics and engineering corporation,” two NICAP members wrote, leveraging their jobs at IBM. “Our discussion would be entirely objective.” The Hills also underwent hypnosis with a psychiatrist, believing, mistakenly, that the process would “clear away the rubble of anxiety and forgetfulness and restore them to complete control.” But what they dredged up made them look even crazier and, to their chagrin, their doctor refused to endorse it.

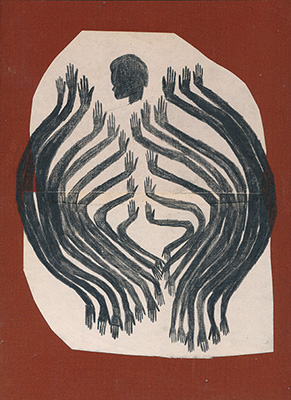

Mis ojos lloran por ti, by Luis Edgar Mejicanos. Courtesy the artist and HESSE FLATOW, New York

If you have notions of a prototypical alien abduction—sloe-eyed, gray-skinned, narrow-chinned creatures conducting anal probes with malevolent dispassion—they derive from the Hills’ hypnosis sessions, wherein the couple came to believe that they’d been brought aboard the craft for medical testing. Betty found the experience fascinating, except for the part where the aliens shoved a long needle into her navel for a pregnancy test. Barney felt like a rabbit in a trap. Bowman writes that he remembered “a small tube about the size of a cigar inserted into his rectum and the eerie sensation of a single finger pressing against the base of his spine.”

As these details emerged, the Hills found themselves the object of a national obsession. Books, articles, and TV shows exposed them to new levels of scrutiny and derision. (Last year, Penguin reissued The Interrupted Journey, John Fuller’s 1966 bestseller about the couple.) Even sympathetic observers assumed that the “abduction” amounted to mangled angst about either their interracial marriage or their childlessness. People egged their car. Someone painted a swastika on their sidewalk. But Betty in particular still treasured the visitation. She had communed with an advanced civilization whose technologies the government wished to suppress. Some years later, she noted approvingly that the needle the aliens had inserted in her abdomen was “now in everyday usage in big city hospitals.”

After Barney died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1969, Betty started seeing UFOs with increasing frequency, sometimes accompanied by black helicopters. She learned “to distrust anyone who offers to analyze anything I find” and avowed that she’d lived a past life as “an English girl, herding geese.” Bowman is acutely sensitive to the pressures the couple must have felt as their concept of reality crumbled, revealing something “esoteric and divisive, something that splintered American communities rather than unified them.” Conspiracy theories were their only solace. When Betty saw a spacecraft after Barney’s death, she assumed it must be looking for him and started shouting at the sky through her tears: “Barney died. He is no longer alive. . . . We bury our dead.” She pointed toward the cemetery and told them they’d find him “by the flowers on his grave.” The ship “rocked back and forth,” she remembered, “crossed the highway, and headed the direction I had pointed.”

For Bowman, “the Hills’ project was one of adaptation”: fitting the square peg of their story into the round hole of the society that had ostracized them. Without the Cold War’s existential threat, would they have believed that they saw a UFO? What if the state had treated them as more than a nuisance, or if the experts conceded that their experience was beyond explanation? Garrett M. Graff’s UFO: The Inside Story of the US Government’s Search for Alien Life Here—and Out There (Simon and Schuster, $32.50), focuses on the top brass and the talking heads who made the couple feel irrelevant. Graff chronicles the nation’s failure to develop a consistent, top-down response to weird stuff in the skies—a program that served both citizens and the national security apparatus.

The state could shrug off the occasional space pancake or anal probe, but it couldn’t ignore its own pilots, who in the Forties had begun to report credible extraterrestrial threats. The Air Force launched Project Sign, its first UFO-tracking initiative, in 1948. Its analysts were overwhelmed with sightings that seemed to defy the usual explanations—ball lightning, weather balloons, meteor showers—prompting the memorably titled “Estimate of the Situation,” a top-secret assessment so incendiary that every copy of it was burned. “The situation was the UFO’s; the estimate was that they were interplanetary!” one of the researchers later wrote. In 1949, Project Sign issued a more measured statement, concluding that most of the 273 incidents were probably meaningless. As for the chance of advanced technical developments from another nation or world, “no facts are available to personnel at this Command that will permit an objective assessment of this possibility.”

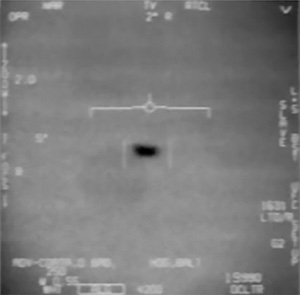

A Navy video still of a UAP, November 2004. Courtesy the Department of Defense

After Sign came Projects Grudge and Blue Book, which leaned just as heavily on bureaucratese to mask their uncertainty. (An official history of the Air Technical Intelligence Center, which oversaw the Air Force’s UFO research, bragged that they had introduced “100,000 new technical terms to the English language.”) Pilots, meanwhile, grew leery of reporting their encounters to a hierarchy that filed them away as oddities. The Air Force promoted the term “unidentified flying object” to give the sightings a scientific sheen, encouraging airmen to tell their stories.

The rebrand didn’t help—a chilling effect had taken hold. J. Allen Hynek, an astronomer who’d worked with the Air Force since the Forties, said that many scientists were less skeptical of UFOs than they would admit in public. He grew frustrated with the official line, which he felt was designed to quell the nation’s suspicions rather than figure out what was really going on. In 1953 he’d joined the Robertson Panel, a secret committee convened by the CIA “to reduce public concern” about UFOs. “Their basic attitude was very clearly an attitude of ‘Daddy knows best, don’t come to me with these silly stories,’ ” Hynek said. In 1959, an ATIC report stated that Project Blue Book was “extremely dangerous to prestige.” The program was terminated in 1969, just before the start of a decade whose scandals would completely undermine the public’s faith in its institutions.

The government’s prickly paternalism—and its annoying habit of rechristening flying objects every few decades, most recently as UAPs—generated countless conspiracy theories, which Graff soberly investigates, down to the last crop circle and cattle mutilation. Most are bunk, but he acknowledges “an active, ongoing cover-up over decades” and believes that “even today, the U.S. government is surely hiding information from us.” (The “even today” seems needlessly charitable.) Hynek was one of the few who saw the advantage of greater transparency. “You can cover up knowledge and you can cover up ignorance,” he said. “I think there was much more of the latter than of the former.”

Suppose aliens do show their faces. What will we call them? How will we introduce them to heads of state at black-tie banquets? One of my issues with Star Trek: The Next Generation is its assertion that intergalactic amity can exist only in an atmosphere of stifling formality. The Enterprise crew are military factotums like those in Graff’s book—their sometimes rigid adherence to protocol means they can barely be trusted to talk to other humans, let alone to extraterrestrials. No one in Starfleet could pull off Joe Simonton’s quick, wordless, water-for-pancakes transaction.

Untitled, by Alexandra Duprez © The artist. Courtesy MEPAINTSME

Or so I thought before I read Robert Hickey’s Honor and Respect: The Official Guide to Names, Titles, and Forms of Address (University of Chicago Press, $80), which argues convincingly for the merits of decorum. This is a stately brick of a reference text, “a record of how officials are directly addressed in English at the beginning of the millennium.” It describes how tenuous and brittle communication is on our planet, and also how ornately beautiful. Though it’s intended primarily for diplomats, anyone who relishes language will enjoy it for its exacting specificity. At last, definitive advice on how to address the wife of a younger son of a marquess; the royal heir apparent of a Malaysian state; the territorial commander of the Salvation Army; the acting president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “The Master of the Horse is an honorary post in the United Kingdom ceremonially responsible for the royal carriages and horses,” I learned. “Astronaut is not used as an honorific,” and “deceased persons are not typically listed on an invitation’s host line.” Should I deliver my calling card in person, I know to leave a note in pencil; if I send a courier, I must use ink.

In a foreword, Pamela Eyring (of the Protocol School of Washington, naturally) wonders if “the demise of protocol is approaching” in an increasingly informal world. But Eyring insists that every detail matters. The place cards, the honorifics, the way that the State Department addresses a chargé d’affaires ad interim. “Why? Because everything speaks.” Indeed, everything does. Revisiting Simonton’s UFO story, I noticed a detail I’d missed. The spaceman, receiving his jug of water, “gave me a salute with the back of his hand—a gesture of thanks, I presume,” Simonton said. Not knowing what else to do, he returned the salute. It was this exchange that got him the pancakes.