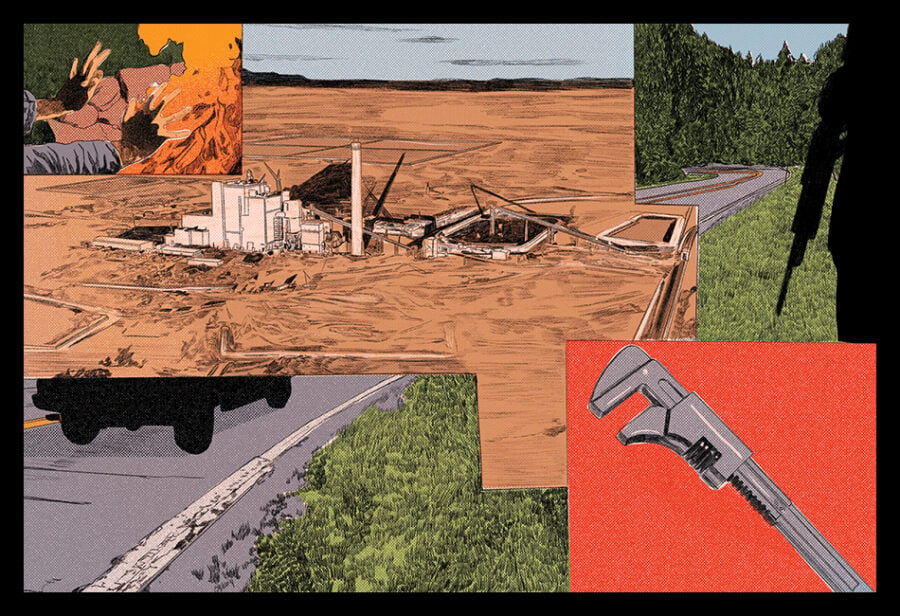

Illustrations by Nicole Rifkin

In the summer of 2016, a fifty-seven-year-old Texan named Stephen McRae drove east out of the rainforests of Oregon and into the vast expanse of the Great Basin. His plan was to commit sabotage. First up was a coal-burning power plant near Carlin, Nevada, a 242-megawatt facility owned by the Newmont Corporation that existed to service two nearby gold mines, also owned by Newmont.

McRae hated coal-burning power plants with a passion, but even more he hated gold mines. Gold represented most everything frivolous, wanton, and destructive. Love of gold was for McRae a form of civilizational degeneracy, because…