Let us follow a Cossack seigneur who is going by way of the Volga to his domains in the steppe of the Don. We are seeking picturesque representations of national life, and in order to find them we shall do best to follow in the footsteps of a great landed proprietor who has been staying in Moscow, performing his devotions in the cathedrals of the Kremlin. It is a joy to the heart of a good Russian to contemplate the town of the sixteen hundred churches, with its ocean of green roofs, its lacework of spires, its domes rising against the sky. He has visited St. Michael the Archangel, where the tsars since Ivan I have slept side by side in their coffins, and he has kissed the reliquaries beneath the vaults of the Uspensky Sobor, the metropolitan church where the emperor is invested with the crown on the day of his consecration.

In the evening his friends have invited him to Petrikief’s, the restaurant famous for the orthodoxy of its national cooking, where Tatars dressed in white serve ukha, or sterlet soup, so dear to the gourmet. He makes his last purchases in the bazaar, in those little booths that run along the vaulted galleries where Muscovite merchants, as impassible and wily as the Turks, sell caravan tea, Siberian furs, or silver-gilt images. Then he departs by steamboat for Nizhny Novgorod, and as he will certainly have some business to do there, we shall have time with him to glance at its microcosm of Russian life.

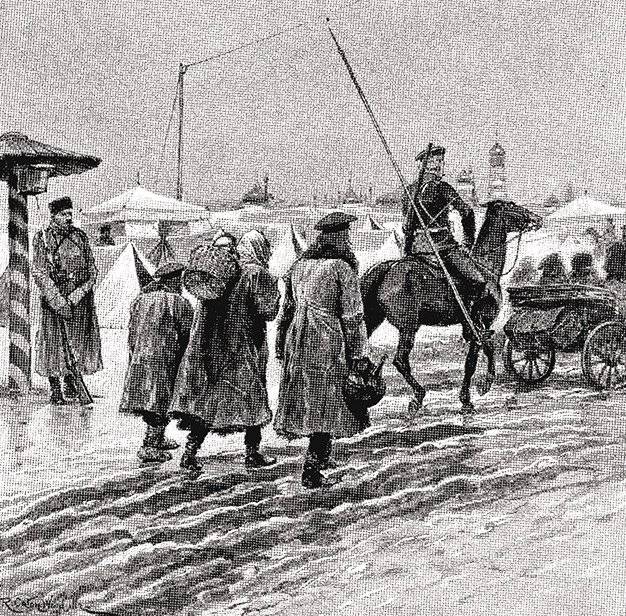

But first the level of the waters of the Volga must be consulted. When the waters are low, the heavy boats, laden with metal and with foodstuffs, run aground on the sandbanks of the river. It is upon this sandy plain that the large city rises: Nizhny, with its wooden houses, its long streets, its Chinese quarter whose pagoda roofs bristle with dragons. Here mysterious boats come up the Volga, each carrying an ethnographic sample of the East. It would require a correspondent of the Pall Mall Gazette to trace the lives which may be seen in Nizhny, where you may study the most abject misery and vice, and at the same time, the most incredible follies of wealth. In a few weeks a Nizhny merchant will drink more champagne than a whole provincial town in France consumes in a year, and spend a fortune such as the entirety of Paris rarely sees squandered within the same lapse of time.

Now let us take our Cossack friend far from these temptations and embark on a steamer going down the Volga to Astrakhan. It meets little boats going upstream, dragged with ropes by women in scarlet petticoats, apparitions who stand out against the brown clay of the cliffs and disappear between the poplar trees. On the banks are but a few villages, which grow rarer as we advance south. Until recently, pirates infested the lower Volga, and local populations took refuge in the interior to escape incursions. Their houses look comfortable, and have an air of cleanliness that distinguishes them from the miserable Russian isbas. In their colonies swarm evangelical sects of all kinds: Moravians, Stundists, Molokans …

Resume the journey and the Russian Mississippi continues to spread before us. Each day we touch down at a great town of the East, Kazan first of all, the city where half the population is composed of Muslims. Lower down is Samara, which the Russians call “the American town.” There is nary an old building, promenade, or tree in Samara; only hotels, public offices, banks, and sunburnt squares. Further still to the south, and one day’s journey above Astrakhan, the town of Tsaritsyn offers the same characteristics: it is the center of commerce between the Volga and the Don.

There we leave the steamer. In a vale between the yellow undulations of the steppe, where the pasturage of our Cossack stretches to infinite distance, we find a hub of business: mills, orangeries, immense stables. His own dwelling is modest, and—characteristic of old Russian manners—entered through an anteroom in which maids see to their needlework. Thus it was, once, in the homes of all seigneurs, and, if we believe Homer, in the atrium of Greek kings.

From “Social Life in Russia,” which appeared in the June 1889 issue of Harper’s Magazine.