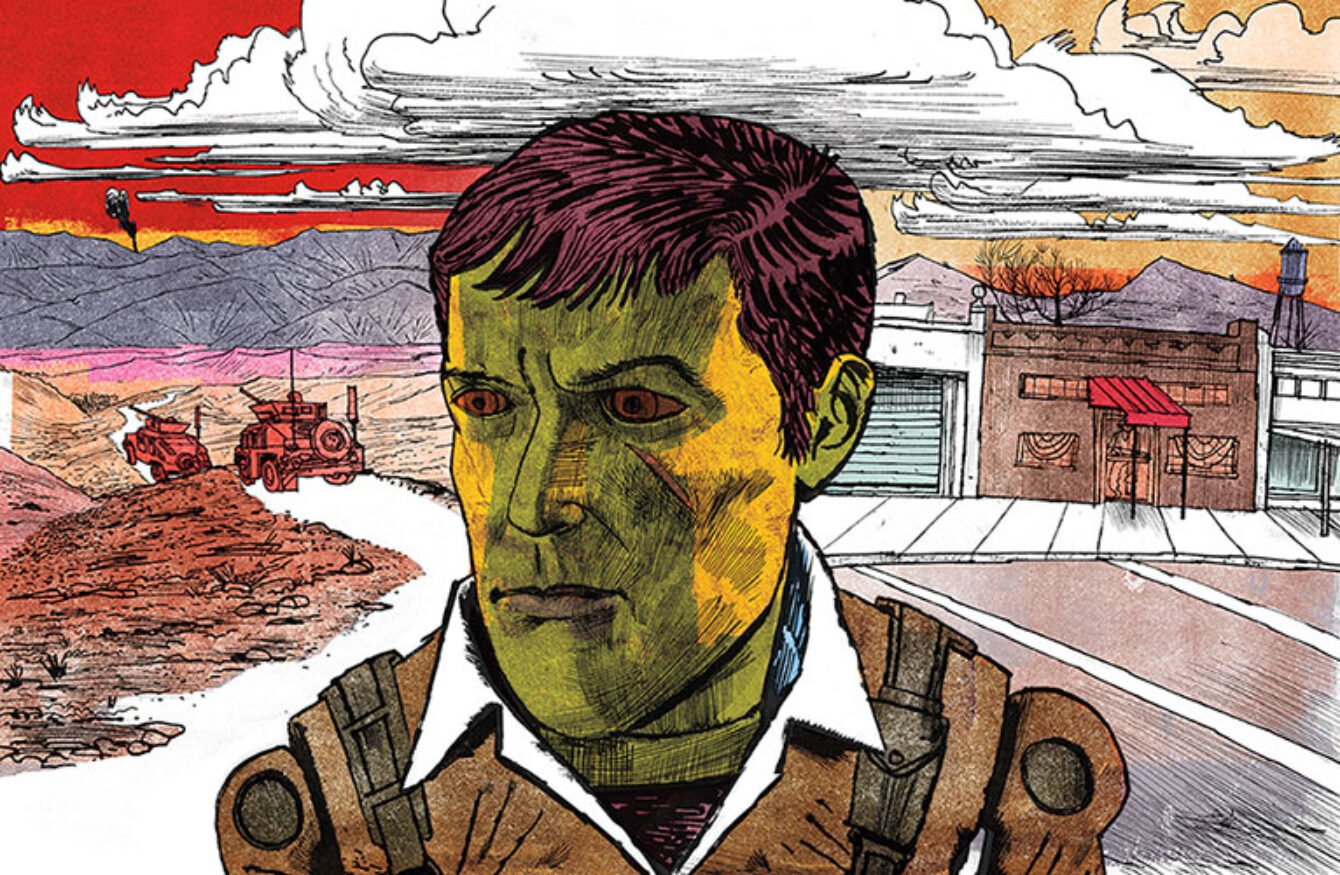

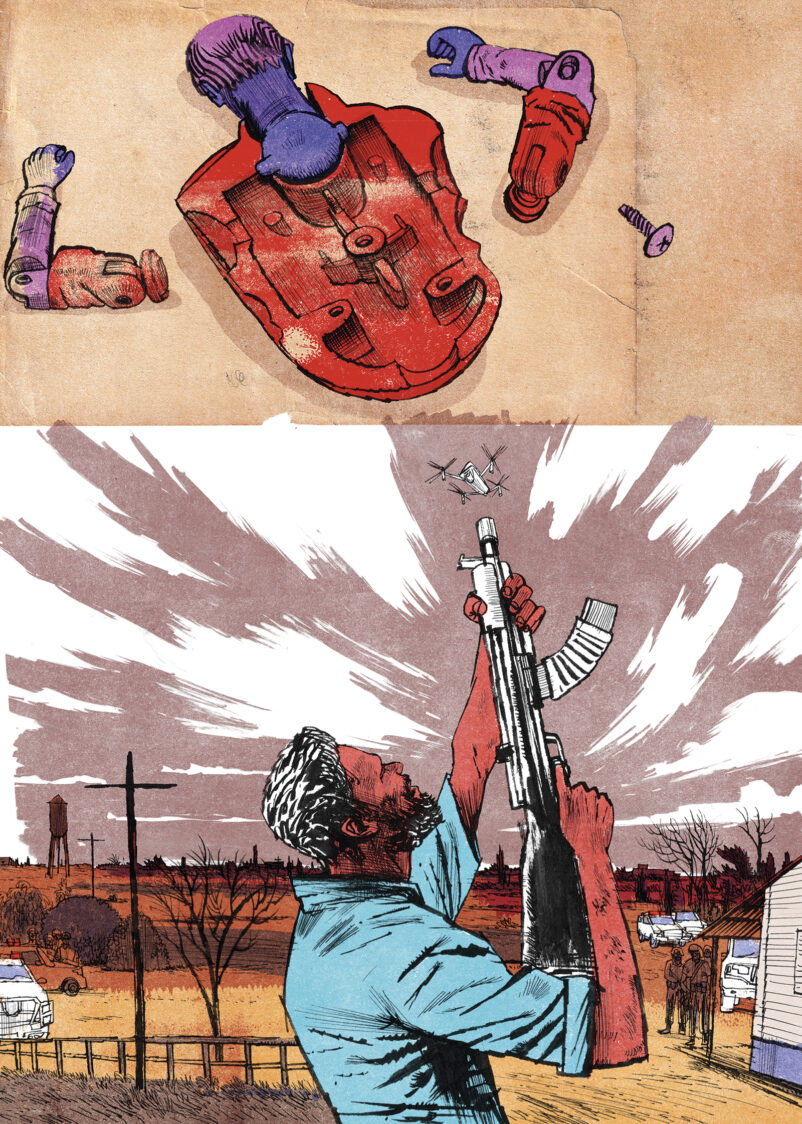

Illustrations by Matt Rota

A late summer sun burned out in the west behind me, blood rays filtering through the Texas sky. Crimson clouds turned gold as I stopped at a gas station in Granite, Oklahoma. At a crossroads a few miles back, when I was still in the Lone Star State, I made a phone call to one Dr. Neil Vitale, proprietor of the G.I. Joe Museum and Repair Shop in a town called Lone Wolf (population 402), telling him I’d be with him shortly.

A museum that repairs broken G.I. Joes in a town called Lone Wolf seemed like an ideal place to visit, that summer of 2022—poetic even, since after a recent divorce I was once again on my own. I was passing through the area on my way back to Fayetteville, Arkansas, where I’d lived with my ex-wife. I spent the season hiding out with relatives in the outlaw potato country of southern Idaho, waiting for the papers to come through.

The good doctor had been waiting around for me all day. I’d expected to arrive at the museum by high noon, but it was closer to sunset. I got caught up in Santa Fe, sharing a final meal with a high school English teacher who had become a dear friend over the past twenty years; she would die of cancer only a few months later. At Salt Fork Red River, before the bridge, a deer ran along the bank, pacing neat rows of green crops popping up in the red dirt. It was good country.

I called Vitale while driving on U.S. 287, a number that made me remember being young, for better and for worse. I am a veteran of the 2-87 Infantry, the Catamounts, a battalion in the 10th Mountain Division. We served the longest single combat tour in the war on terror, roaming eastern Afghanistan for sixteen months, from 2006 to 2007. We killed a lot of people. We only lost four of our own that deployment. We’ve lost many more since. It was a lifetime ago but seems close enough. PTSD is like a time machine embedded in your brain that glitches unpredictably and takes you back to relive the worst moments in your life. My nephew was born while I was in Afghanistan. He just got his driver’s license; he plays the flute and is first chair. I’ve heard our brigade has one of the highest suicide rates in the Army; a bunch of us, including me, have criminal records. Most of us draw some form of disability. A lot of us are dead.

god bless america read a sign down the road from the Granite gas station, blue and red sans serif letters against a white background. I noted it and moved on. In the next town over, on the main street in Lone Wolf, I saw a man putting out a G.I. Joe flag as I parked. There was a World War II Willys Jeep parked out front to advertise the museum, which was housed partly in an old grocery store. My dad had restored a Jeep like this when I was little. It had been a long drive, and I took it all in.

Earlier that summer, on my way out to Idaho, I’d passed through Fort Riley in Kansas. I was sleeping rough—saving money by rolling out a sleeping bag in the back of my Subaru at rest stops. It’s not a bad way to travel, but after a day or so you begin to smell. I knew that at Fort Riley I could go to the base gym, use the shower, emerge refreshed. As I left, I called my old battalion commander, Chris Toner, whose divisional headquarters had been here before he retired as a colonel in charge of all the Warrior Transition Brigades. He’s now a big wheel at the Wounded Warrior Project.

It was my command sergeant major, Jose Vega, who answered the phone. He wanted to know if I’d heard about Anthony Kienlen, who had been in Sean Parnell’s platoon and had apparently gone “full outlaw.” I stopped and pulled out my Catamount yearbook. I asked him to repeat the name, twice; I didn’t know any Kienlen. He’d been in Bermel; I’d been, well, almost everywhere but Bermel. I looked him up in the yearbook. He looked like a baby, which he was—he had joined up with the Army a week after high school graduation. Bermel, one of the most dangerous places on earth, was his university and graduate school.

And now he’d gotten into some trouble. One day the year before, problems with the wife devolved into attempted suicide—he cut himself hoping to bleed out—and, worried for his life, she called the cops to their house on Turkey Ranch Road outside Wichita Falls. Sheriff David Duke (his real name)sent out a posse to deal with the suicidal combat veteran turned emergency room nurse. The scenario that played out wasn’t the finest moment in the history of crisis management.

All hell broke loose. Kienlen didn’t want to go to a facility and the sheriff’s office rolled up on him heavy, a bunch of north Texas good ol’ boy deputies and other law enforcement officers kitted out like Blackwater operators. Kienlen shot their surveillance drone—freehand, from a standing position, with a Remington Model 700 rifle. Every time I’ve mentioned this fact to anyone with combat experience, they’ve been sufficiently impressed. It’s good shooting, though it is also highly illegal. He also allegedly shot at the police officers, and maybe at their cars too, all of which accounts for his having spent, by that point, a year in jail in pretrial detention. They didn’t take kindly to the whole situation. They have him on sixteen counts of attempted murder of a peace officer. A charge that strikes me as vaguely off. Catamounts don’t “attempt” to kill. We either do or we don’t.

I was born in this country, in Utah—the closest thing to Kandahar the United States has to offer—but I was raised overseas, in Turkey and Germany, from age six to eleven, before coming back to attend schools in suburban Virginia that were mostly populated with other military brats, diplomats’ kids, and spy progeny. The CIA’s main training base was just up Colonial Parkway from where I did my freshman and sophomore years. I spent my last two years of high school on scholarship at a boarding school in New Mexico that was founded by the king of England and Armand Hammer, and had a student body consisting mainly of international students.

One constant in my peripatetic childhood was G.I. Joe. G.I. Joe is there, as the theme song went, and I loved it for that. It was a multimedia form of love—I loved the toys, the comics, the cartoon. Now you know, as the catchphrase put it, and knowing is half the battle! I particularly loved the animated G.I. Joe: The Movie, released in 1987. This is the one with Serpentor, the Cobra Emperor, a creation of Dr. Mindbender, who himself was an orthodontist until he turned, well, Mindbender. He was a kind and honest man, who tried to build a brain wave stimulator to relieve dental pain; when he tested it on himself, it didn’t relieve dental pain so much as turn him into a monster and the premier mind control expert for the terrorist organization known—throughout the franchise—as Cobra.

To create Serpentor, Dr. Mindbender partnered with Destro, a Scottish arms manufacturer of noble ancestry who wears a metal face mask. Destro is the on-and-off paramour of a perpetually leather-clad European terrorist called the Baroness. Together they send out Ahnenerbe-style units to harvest DNA from tombs and relics to create a “composite clone” who possesses “the military genius of Napoleon, the ruthlessness of Julius Caesar, the daring of Hannibal, and the fiscal acumen of Attila the Hun.” Serpentor, the emperor, deposes Cobra Commander, who breathes in spores that cause him to become a reptilian being. And so on and so forth.

The Serpentor narrative, of course, was just the B story to the hero’s journey of Green Beret Lieutenant Falcon, who finally lives up to the martial prowess of his brother Duke after passing a series of tests in Sergeant Slaughter’s training regimen and seeing some real-world combat in the Himalayas. I watched G.I. Joe: The Movie just before we left for Turkey, and then each subsequent summer, at my aunt Debbie’s house, when we’d return to Utah.

I have an encyclopedic recall of G.I. Joe lore, which I learned from the hilarious and strangely subversive trading cards written by Larry Hama, a Vietnam War veteran of Japanese descent who also wrote the excellent G.I. Joe comic for Marvel. This was in the early Nineties, when my father was stationed in the Aegean city of Izmir as the Gulf War kicked off; the terrorist threat to Americans in the area meant I got time off school to play Nintendo games and watch cartoons. When we visited the PX—someone bombed the commissary, so it was closed for a spell—I finally got to purchase the latest G.I. Joe comics.

I still remember them as clearly as I remember watching the war live on CNN; they told the same story I was living but with a different spin, which was a good way to get some perspective on the official line. I read about the invasion of the fictional country of Benzheen, the financial interests involved, the behind-the-scenes scheming. I learned about tragedy from what was happening around me, but also from reading those comics. It was a big deal in one issue when some Joes got taken prisoner and executed by what was called a S.A.W.-Viper, a private military contractor working for Cobra. The Viper overstepped, misunderstood his orders. I’ll argue any day of the week that Larry Hama was as prescient and influential—particularly to my generation of soldiers—as any other writer of his era.

I’m a sucker for museums. On this particular stretch of my drive, I had half a mind to visit the General Tommy Franks Leadership Institute and Museum in nearby Hobart. Franks’s career arc as both a soldier and a veteran was the stuff of legend; it’s fair to say he’s had a different experience than me and my peers. He began his Army career in this part of the country: Fort Sill, home of Army artillery, wasn’t too far down the road, over in Lawton. Geronimo is buried there, in Beef Creek Apache Cemetery—Apache were held there as prisoners of war on a military reserve. As CENTCOM Commander on 9/11, Franks (a high school classmate of Laura Bush) oversaw the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, appeared on stage with Wayne Newton, and—wisely—retired from the Army while both wars still looked something like victories. Afterward, Franks slouched toward the semi-karat golden arches, joining the corporate boards of Bank of America, Chuck E. Cheese, and the like—still a man on the make. He was on the cover of Cigar Aficionado. Iraq burned, but Tommy Franks remained on the board of Outback Steakhouse.

In Lone Wolf, ten miles from the Franks Institute, Dr. Vitale took me on a tour of the museum he built in tribute to the G.I. Joe, that real American hero. It was obvious that he’d done this many times before; he had the patter down, and incidentally he’s really a doctor, I bet a pretty good one. Doctors carry themselves with an aura of authority that is often combined with an aversion to answering questions in favor of issuing diktats. Vitale is trim, in his mid-sixties, with a well-groomed beard, and he wore a cool custom polo shirt that I immediately envied. It was a forest green, of course, with g.i. joe museum stitched in plain yellow lettering that curved above an old-school logo, of a helmeted Joe head filling out the swoop in the J.

Inside the museum was a large Green Beret display and diorama, almost a full A-team. I’m a regular leg infantry veteran; there are plenty of grunts like me. But over the years I’ve worked with, for, and around enough Green Berets to gain a certain respect for them. They inspire a different reaction in me than, say, Navy SEALs. They even dispatched a team from Tacoma, Washington, to pay their respects and look after me during my brother’s funeral in eastern Idaho more than a decade ago. They had come out, in part, to commemorate the fact that my brother had once risked his and his crew’s life to save an A-team trapped in a steep mountain ravine, descending in a helicopter a thousand feet down a treacherous canyon, with barely a rotor’s clearance between the valley walls—pulling this maneuver twice to extract the soldiers, when no other pilot in his unit could.

Elsewhere in the museum, a poster showed twenty-three G.I. Joes neatly arranged in rows, the various incarnations of the action figure: pilot, astronaut, French Resistance fighter, mortar man. The caption read: “Old soldiers never die. Your Mom threw them away.” When I was a soldier, one of the stats repeated often was that twenty-two veterans killed themselves per day. Coming home, you may have heard, we’re not always on the surest of footings. As I walked through the museum, I tried to remain conscious of the fact that this tour was not about me—I concealed my exhaustion, my irritability. Symptoms, I imagined, of having finally gone off Ritalin, the last of the medications that Veterans Affairs gave me to help my brain function correctly. None of them helped much.

The place was a labor of love. At its root it was a noble project, I thought, as Vitale told me about an octagonal carriage bolt cabinet he’d found left for dead and restored lovingly over a couple of weeks. The museum and Dr. Vitale both deserved better than me in this moment. I was fueled entirely by coffee and a 5-hour Energy drink I’d slammed at the gas station in Granite.

Our last stop was the repair shop, which was situated near the space diorama and the giant D-Day diorama. It made a certain amount of sense, Vitale giving me the tour in the order that he did. Initiated thus into the mysteries of the G.I. Joe Museum ethos, I appreciated the significance of what the doctor was doing there, or what I imagined him to be doing. Which is: to take pieces of trash—things your mom threw away—and turn them back into treasures. He repairs the figures for anyone who sends them in. It was a paean to community, as much as anything else, and a family affair: the reason it’s in Lone Wolf is that the doctor’s wife is from there, and their daughter paints the murals. The museum is a variety of outsider art and a beautiful one at that. Vitale claimed it was a way he could play with G.I. Joes without anyone thinking it was weird, but let’s be honest: it is weird, just weird in a good way.

You have to see the place through Vitale’s eyes. Enter the building and look to your left, at the wall separating the museum from the street, and you’ll see the story of g.i. joe. The eye, however, is drawn to one of the daughter’s murals. Between the sign and the mural is an easel with the original 1964–65 run of the first Joe action figures (don’t ever call them dolls). There’s Action Soldier, Action Sailor, Action Marine, and Action Pilot—each of their faces is painted on the walls. Looking at them, I thought of the walls of Herculaneum and idly speculated about what tourists, two thousand years in the future, would think if this whole display were excavated, what conclusions about our civilization they would draw from the museum, which has more G.I. Joes than the town has residents.

By November, I was back in Arkansas, and the leaves were off the trees in the Ozarks. Just before Veterans Day, I drove across Oklahoma into northern Texas and checked myself in to a hotel in Wichita Falls. I wanted to see Kienlen and scope out the scene of the crime for myself. Obviously I had my own opinions, but I hadn’t seen the land, hadn’t spoken to the people affected. At the junction where Turkey Ranch meets the larger arterial road into the city proper, there’s a Dollar General—the beating heart of rural America. The lady behind the counter had been working when the shooting occurred. I asked her about it. She thought the sheriff’s office was making an example out of Kienlen and didn’t think it was fair. She was there when the police had set the cordon up, she had heard the gun shots, none of which hit the deputies.

“Kienlen always was a good shot,” one of his company mates, Stephen, told me over the phone. Stephen got into a little trouble himself when he emptied a fully loaded .45 magazine into a television set in his backyard in Maine; he’d gotten upset at the television, but hadn’t considered that he was within a few hundred yards of both a school and a police station—his lawyer was ultimately able to plead it down. Stephen was worried about Kienlen, and he had what I thought was a balanced perspective on the situation. Kienlen hadn’t wanted to kill the cops, Stephen figured, he just wanted them to go away.

I met with Kienlen’s lawyer at a diner off the highway, a few minutes from the jail—for breakfast, but mostly so he could scope me out before we went to see his client, my old comrade from the war. I wore a tweed blazer, a Hermès tie that a Latvian ex-girlfriend had given me, and some of my Army flair pins. The lawyer, Dustin Nimz, wore fancy black cowboy boots with colored embroidery and an expensive-looking cowboy hat. He removed it politely and left it sitting on the table, and when the waitress refilled our cups a drop of coffee stained the leather on the underside of the brim. I could see him wince.

Afterward we drove to the jail—287 once more—to meet with Kienlen in one of the attorney booths, number five. It was a small room, ten feet by ten, with a large bulletproof-looking window running down the middle. I once visited one of the Atomic Energy Commission’s first nuclear reactors, and the way this room was constructed reminded me of how the uranium was separated. I’m not sure which of us—the lawyer, the writer, or the prisoner—is the radioactive one in this metaphor.

There was a phone, like in the movies, but we didn’t use it. They’re ungainly and, more importantly, rumored to be tapped. Instead we use the document slide to talk, our voices vibrating through a gap about an index finger long and several inches wide. It is made for sliding papers back and forth between lawyer and client, not for communication any other way, and the acoustics were skewed. It was a bit like watching a movie in which the dialogue is out of sync with the actors’ mouths.

“Shit, man, this sucks,” I said, when nothing else immediately came to mind. “You doing okay?”

He looked at me. We didn’t know each other, but we deployed together. He knew he didn’t have to spare my feelings.

“Nah,” he replied. “When I came in here, it’s because I was suicidal. Over the past year, my meds haven’t changed, I’m not getting any kind of treatment. I’m not sure I’m any better off.”

I squirmed around in my chair, told him he looked like he needed some sunlight. In truth, he looked like he was back in a war zone. The food was bad. He had credit in his commissary account, but the jail price gouged everything, from Honey Buns to ramen noodles.

“I’ve heard ours is significantly more expensive than most jails and much more expensive than the prison system,” the lawyer, Nimz, told me of Wichita Falls.

“So who’s making all the money off that?” I asked, knowing the answer. Sheriff David Duke, inside whose jail I was sitting, locked in a room with a lawyer and a man accused of sixteen counts of attempted murder.

Kienlen seemed hypervigilant. I thought about his yearbook photo, the kid who joined when he was eighteen.

“We got older,” I said. “Look at this shit. I got gray hairs, man.”

Kienlen laughed. He no longer looked like a baby; he had gray hairs, too. In fact, he looked rough for his thirty-six years, despite sparkling hazel eyes and a fresh haircut. He was doughy from a year of antidepressants and jail food, his skin slack and sallow. I asked if he was working out, doing his push-ups, and he said no. Too depressed.

The lawyer preferred I not talk about the case in there, and I suppose there was no need. The facts of the matter were fairly cut-and-dried, the only issue being how the court would respond to them. My response was a human one: This is a guy I went to war with. There aren’t that many of us left. We talked about some of our departed comrades, most of whom had died after the deployment. There was more than one heroin overdose, a cruel irony. I told him that the commander and the sergeant major were worried about him, we were all working behind the scenes, but there was only so much we could do, and it would all move slowly. Over the course of my career, I’ve seen a number of soldiers in captivity, and nothing ever moves as quickly as one would like.

Kienlen was hoping he could bond out at the end of the week, but I can only assume the sheriff’s office really had it out for him. He was in the process of filling out his release paperwork after his previous bond hearing when they dropped two more attempted murder charges on him for good measure.

The topic of his platoon leader, a Pennsylvania politician named Sean Parnell, came up. Parnell’s senatorial hopes had ended amid allegations of domestic violence and child abuse. Parnell, he said, had not been in touch. I could tell that disappointed him; he said that most of the people he used to call were dead. I told him he could always call me. He hasn’t taken me up on it yet. Part of me is glad.

Iarrived at the courthouse two days later, wandering through a building in disrepair until I found the right room. It was about twenty minutes before the hearing was supposed to begin, and there was only one other person there, a lanky blond man with a beard, carrying a Coke and a thick red folder. He wore north Texas formal wear: a western sport coat and necktie patterned with the Texas flag, khakis, boots, and a lapel pin featuring the flags of both the United States and the Lone Star State. This was Patrick Bradford, the investigator who had written the arrest warrant affidavit.

I didn’t know this when I introduced myself, casually asking him if he was there the day of the shooting, what it was like. “I’ve never been in combat,” he said, “but that day …” He let the sentence hang in the air. It seemed like he’d told this story before, to people more impressed by that line than I was. I clarified that I wasn’t just here as Kienlen’s buddy, that I was a writer, adding that we were all just lucky everyone was still alive. With a rifle, Kienlen could have killed them all fairly easily, it seemed to me, if he’d really wanted to. At that, Bradford declined to say anything further about the case.

I tried a different tactic. I had spent some time in town, getting the lay of the land. I saw a rolling prairie bisected by the Wichita River. Supersonic jet trainers, T-38s, from nearby Sheppard Air Force Base flew overhead. From my car I saw military pilots training over longhorn cattle penned in by barbed wire. The roads are all shitty around here. The city seems to have been crafted from the worst parts of Texas and Oklahoma—the way Washington, D.C., was crafted from the worst parts of Virginia and Maryland. There’s plenty of prosperity in Wichita Falls, but I didn’t see much of it; it kept itself neatly confined to the fenced-off parts of town. I saw low-rent strip malls and houses in need of new siding. There is a building adorned with silhouettes of sexy women as Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove on the side of it—a strip club called Bombshells’ Topless. This might as well be Fort Worth, Amarillo, or San Antonio, though it’s greener than the rest of Texas. Still, there’s an aesthetic likeness.

This is a tough town, I said to the investigator. He said that when the hearing was done, I should walk out of the courthouse and look for the tall building adorned with swastikas—of the Native American variety. I’d seen them the day before, Kienlen’s lawyer’s office is in that building, but I played dumb. I was curious what effect he was trying to achieve by telling me this. I wondered if it might be a bad idea to antagonize him. Kienlen had certainly done that. From the affidavit for arrest issued on June 27, 2022:

Dispatch advised in route [sic] deputies that Anthony was making statements that he wanted officers to shoot him. Upon arrival, Deputies Vandygriff, Biter, and Garcia positioned patrol vehicles in the roadway approximately 135 yards north of the property on Tuerkey [sic] ranch road.

While waiting for additional units to arrive, Kienlen fired shots from a rifle in the direction of Vandygriff, Biter, and Garcia.

After additional units arrived, Kienlen moved to a shooting position on top of a golf cart that was protected by a cement wall. From this position, Kienlen continued to shoot towards Vandygriff, Biter, and Garcia as well as Captain Randy Elliott, Sgt. Rob McGarry, and Deputies Eric Wisch, Patrick Bradford, and Amanda Ward. Kienlen also shot towards Wichita County Sheriff, David Duke and Department of Public Safety Texas Ranger Matt Kelly…

During the attacks, Kienlen shot at and struck a drone from the air that was operated by TPW Game Wardens.

During the standoff, Kienlen’s wife relayed information to the 911 dispatcher that Kienlen stated that he would “Kill them all if they come in the gate.”

Of course, they didn’t all come in the gate, so he didn’t kill them. The situation was settled peacefully, no one was hurt.

Kienlen shuffled in, wearing a black-and-white jumpsuit whose colors had smeared together into a kind of grimy gray. Despite their relative statuses, he seemed to have a solid rapport with the deputies who guarded him. I overheard him tell Deputy Flemming, a guard with a bushy beard and bright smile, that he was in the Army seven days after graduating high school. The deputy laughed at that.

I met Kienlen’s wife and mother in the courtroom, dressed in their Sunday best. “They’ve pulled so much underhanded shit,” his mother told me. It occurred to me then—and not for the first time—that our war had come back on their shoulders. After the hearing, I found myself stammering a sort of apology for this. We went away and were changed, a change that had a ripple effect on everyone in our lives. I saw the way the war aged my parents and my siblings who hadn’t gone, all on account of the way it changed me and my brother. It is a phenomenon they leave out of the recruiting brochures.

Kienlen’s bond was set for $1.6 million. His mother found a bondsman who would secure it. Soon he would be back home, ankle monitor secured, preparing for his trial and wondering what a jury of his peers would think. What, I wondered, is a jury of one’s peers for a guy like Kienlen? What does that look like? I’m his peer, as is Stephen, but there aren’t that many people who have been where Kienlen’s been, done what Kienlen’s done. At least, for the time being, he would be out of jail. For my part, I figured it was time to get back on the road.

On the way out of Texas, not yet over the county line, I got nervous and called a friend who used to work for the Secret Service to tell her I might have just annoyed some cops in north Texas, that I was still in the county, and that if I got pulled over—well, to be ready for a phone call. I wouldn’t feel safe until I made it to Oklahoma.

“Fuck, man, he terrified those redneck cops,” I texted my old Army roommate and war buddy—Tony is his name. He had been in Bermel for a while; I wanted to tell him about Kienlen, see what he had to say.

“I bet man, shit, he’s shot at people who fought to the death!” Tony texted back. “Once you get in that heat of battle, you lose all senses.”

Tony had driven a couple hours out from his home near Boise to meet me at my grandfather’s farm in southern Idaho that summer. He’s a good friend, had come to check on me after the divorce. We try to look out for one another. He has four kids, loves his family, his wife, his church, physical fitness. He’s done a pretty good job of staying sane since the war, and even still, it gets to him. He did a second tour that was bad too. The part of Idaho we were in looks a lot like the part of Afghanistan we served in; on the way up to the reservoir to skip rocks and go fishing, Tony started to feel the old feelings. I felt bad for not warning him. He has a kid about the same age I was when I started playing with G.I. Joes.

I was racing a thunderstorm all the way through Oklahoma, on bad tires, with questionable brakes. I pulled off in Okemah and decided to wait out the rain at a small casino off the highway. The security guard noticed the Combat Infantry Badge on my lapel. Turned out he had served in the 10th Mountain Division, an MLRS guy, launching rockets. He loved it, spent some time in Korea, came back home. He asked what I was doing in town, and I told him about Kienlen. Bear in mind, me and the Creek security guard, we had never met each other before.

He got solemn, grabbed my arm, and asked how our brother was doing. “Brother,” that was the word he used—American veterans, one big dysfunctional family. Not great, I admitted. He told me he’d be praying for him, then led me past the slot machines and introduced me to an old Korean War vet sitting in the café. I was back around people I trusted. Sitting with my new Creek friends in this casino in Woodie Guthrie’s birthplace, I was grateful to be back in Indian Country. I was grateful to be in Oklahoma. I was grateful I wasn’t Kienlen and could cross state lines.

Now you know, as the slogan goes, and knowing is half the battle.