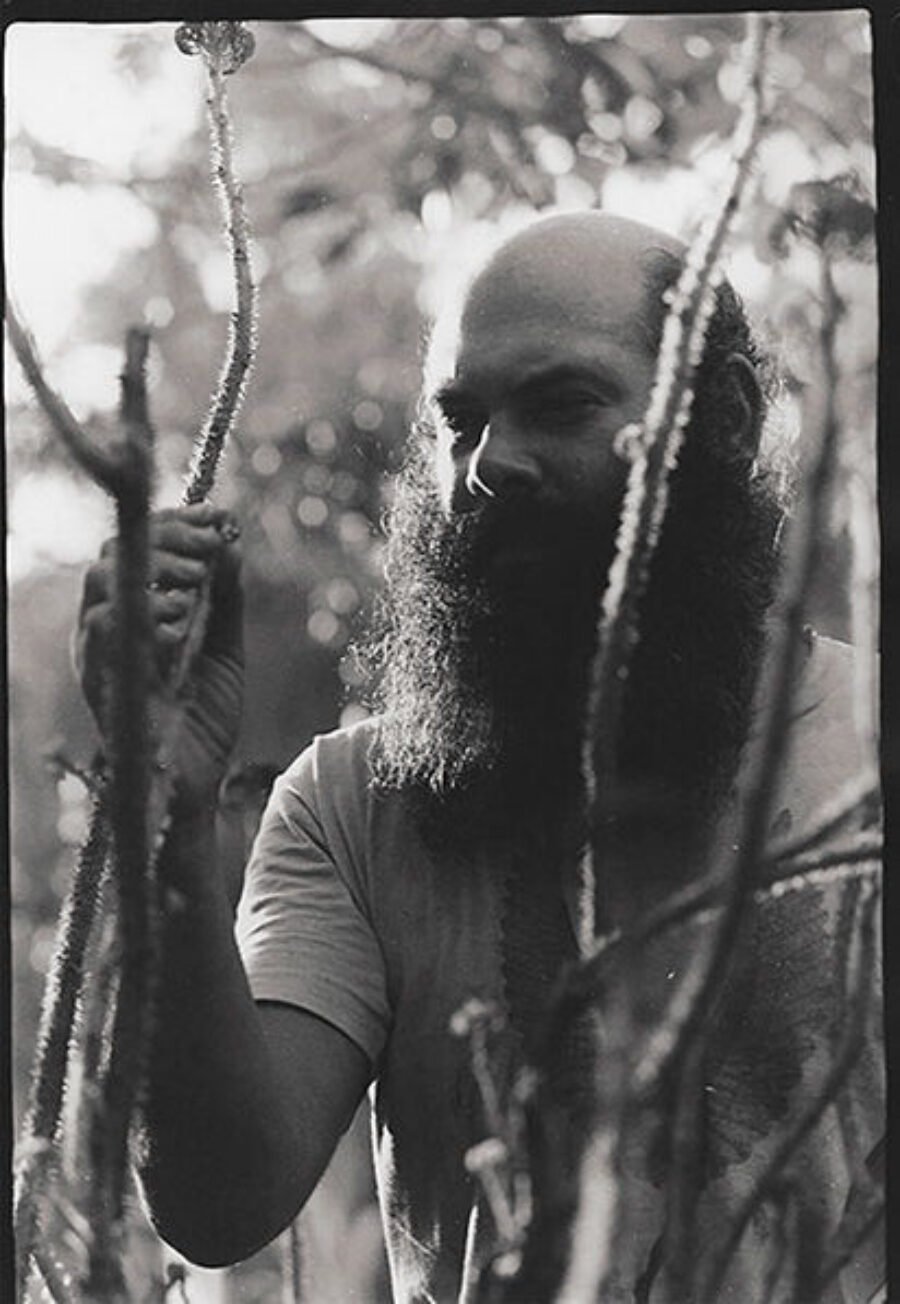

Andrew Weil in Colombia, early 1980s. Courtesy the author

In the summer of 1968, I moved from Boston to San Francisco to start a medical internship at Mount Zion Hospital, exchanging the comfortable familiarity of the East Coast for the turmoil and tumult of the West. The Bay Area was the epicenter of the country’s social upheaval—the previous year’s Summer of Love, which had drawn thousands of flower children to the Haight-Ashbury district, was already a memory. Speed freaks and panhandlers now outnumbered the hippies, and amphetamines had displaced LSD. There was an ambient anger in the air.

For the first two months, I house-sat a Victorian home on Divisadero, a few blocks down from Haight Street and a fifteen-minute walk from the hospital. In addition to my duties as an intern, I volunteered at the Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic, a model for the free clinics that were cropping up in many American cities at the time. The clinic occupied the second floor of a building on the corner of Haight and Clayton, with bay windows overlooking the street.

In my final year of medical school, I had designed and conducted the first placebo-controlled, double-blind, human studies on cannabis. The findings were reported in a lead article in Science and made news around the world, including on the front page of the New York Times. One of the conclusions was that marijuana was a “relatively mild intoxicant” that had less of an impact on the body than alcohol. My study cost less than one thousand dollars, raised without governmental assistance.

I hadn’t smoked pot with any real frequency until this period in medical school. And even though I’d learned that if I had to, I could not only function but function well under the influence, it was clearly prudent not to use it when I was working. Of course I knew that others did. At the hospital, stoner nurses, orderlies, technicians, and other staff would sometimes slip outside for a toke or two, especially when things were quiet. Our resident dealer was an X-ray technician I’ll call Tom, who always had good weed.

One weekend, I was on duty in the pediatric emergency room, a famously quiet service. Seriously sick children went to the nearby UCSF Medical Center; we got the occasional cuts, contusions, and stomach aches. A nurse I’ll call Mary, who I liked a lot—she was bright and greeted everyone with an unusually warm smile—was on the receiving desk. I was upstairs, holed up in a dismal room that interns used, furnished only with a creaky single bed, a desk, a chair, and a nightstand with a telephone that I wasn’t expecting to ring the entire weekend. I had a good novel that I was hoping to dig into.

I was feeling drowsy when I was startled by a firm knock on the door. No one had ever visited the room while I was in it. It was Tom. “I heard you were up here,” he said. “You must be as bored as I am. This place is asleep.” He pulled up a chair, propped his legs on the bed, reached inside his white coat, and pulled out a joint. “Want to get high?”

I hesitated for a moment, then said, “Sure, why not?” Based on past experience, the chance of my being called to attend to anyone in the pediatric ER seemed negligible. Tom lit up, and we passed the joint back and forth, taking pleasure in the act, its illicit nature, and in each other’s company. After smoking most of the joint, we talked for a while—our conversation interspersed with long pauses as we savored the moment. “I should get back to my station,” Tom said as he got up. “Catch you later.” I waved goodbye from the bed.

It couldn’t have been more than a minute or two after he left that the phone rang. “Dr. Weil, you’ve got a case in the ER,” Mary informed me, “a twelve-year-old boy with a scalp laceration that needs to be sutured.” So much for passing the time pleasantly stoned.

I washed my hands and face in the men’s room down the hall to get the odor of marijuana off me, put on my white coat, checked my appearance in the mirror, and confidently strode off to the ER to be Dr. Weil. The only people there were Mary, the boy, and his worried mother. Mary had the patient cleaned up and sitting on the edge of an exam table. I greeted him, inspected the cut, and assured him and his mother that repairing it would be easy and fast. Mary had set out everything I needed. As she turned to leave, she passed close by me, gave me an odd look, and said in a low voice, “When you’re finished here, doctor, I’d like to speak to you in private.” Then she walked out of the room, shutting the door behind her.

Her words sent a bolt of fear through me. She knew! She knew I was stoned. What would she do? I closed my eyes, took a deep breath, and with great effort put my fear aside in order to do my job. I sewed the edges of the wound together neatly and quickly, causing the boy as little discomfort as possible. He was most cooperative, his mother most grateful. I sent them to be discharged, cleaned up, and walked out to meet my fate. Mary was waiting for me. “Step in here,” she said, leading me into a tiny supply room and closing the door. I couldn’t read her expression. My heart was beating very fast.

“I don’t know how to tell you this,” she said. “I’m on acid.”

There was no further action in the pediatric ER that day or the next. Mary got to rest as her trip wound down, and I never smoked pot on duty again.

When I finished my internship year in San Francisco, I moved east to begin a two-year stint as a lieutenant in the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS), stationed at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in Chevy Chase, Maryland. This was in lieu of serving in Vietnam. It was not a fun time to be near the nation’s capital, especially after an exciting year in the Bay Area. Long a Democratic pork barrel, NIMH, for the first time in its twenty-year history, found itself under a hostile Republican administration that was demanding an accounting of what it had done with its funds. One area of vulnerability was marijuana, a focus of increasing social concern. Three years earlier, NIMH had received more than $450,000 from Congress to research pot—and I felt they had little to show for it. The institute had hired me to coordinate marijuana research in Chevy Chase, then promptly rescinded the offer. Perhaps they resented being scooped by my Science article; I imagine the Nixon Administration’s antidrug stance made them wary of research on illicit drugs.

I was told instead to report to the Narcotic Farm in Lexington, Kentucky, to spend two years working with incarcerated addicts. If I refused to go, I would lose my Public Health Service commission and be eligible for the draft. I asked well-connected friends to pull some strings at NIMH. They did, forcing the institute to take me on. When I got there, I was put in a windowless office in the Barlow Building on Wisconsin Avenue, hardly larger than a storage closet, with a phone and nothing to do. My boss was a pleasant man who didn’t know why I’d been assigned to him or what to do with me. From time to time, he gave me grant proposals to review; otherwise he left me alone. Okay, I thought, I’ll play along. Better than being in Vietnam.

I rented a house in rural Virginia, a forty-five-minute commute from Chevy Chase. It had a swimming pool in a huge backyard that led to woods with a rushing stream. On weekends, I invited friends out to cook together, get stoned, listen to music, and talk politics. My friends had jobs in various federal agencies, from the Justice Department to the White House; as antiwar protests intensified and divisions in the country widened, we had a lot to talk about. And all this was made more interesting by our experiments with LSD and MDA.

My plan to lie low at NIMH failed. Requests for interviews started coming in from the media, from universities, from congressional committees, and from government agencies. People who had read my article wanted to talk to me about marijuana. NIMH turned them away, first saying I was unavailable, then that I didn’t work there and they didn’t know how to reach me. This response encouraged more frequent and more persistent inquiries: What did I have to say about marijuana that NIMH didn’t want people to hear? My mail was opened and kept from me. I was asked unfriendly questions about why I was making unauthorized contact with reporters and legislators, and warned that I was not allowed to speak to anyone about marijuana or drug policy.

This tension soon became intolerable. As the end of my first year approached, the USPHS unexpectedly renewed its order: I would be required to report to Kentucky on July 1, 1970, to complete the remainder of my service at the Narcotic Farm. I felt I was being punished. I informed the agency that I considered the order illegal, would not go to Lexington, and would continue to report to my office at NIMH. July 1 came and went. The USPHS declared me AWOL, terminated my salary, and threatened to revoke my commission. At NIMH, people avoided making eye contact with me. A hearing was scheduled. I was advised to get a lawyer. At the hearing, I realized that I had no place in the system and no desire to be a part of it. Until then, I had felt wronged and thought I deserved fair treatment. Now I just wanted out.

Ultimately, the Selective Service System reclassified me 1-A, meaning I was available for military service, and informed me that I would get no credit for the year I had just completed as a commissioned officer in the Public Health Service. I ruminated about what to put in a letter to my draft board in Philadelphia. I decided not to hold back. I vented my anger about how I’d been treated at NIMH, and said the experience left me unwilling to do any sort of alternative service for the U.S. government. I went so far as to say that I could no longer practice Western medicine in good conscience because I rejected its philosophy and thought its methods did more harm than good.

I received their response two weeks later. I opened the letter with trepidation to find that I had been granted conscientious objector status without a hearing. That was unheard of. Were draft boards beginning to realize that people like me were not worth the trouble? An astrologer friend told me I was in the midst of my “Saturn return,” a turning point in life marked by that planet having completed one orbit around the sun since my birth. It could usher in a period of happiness and financial freedom or one of disaster. I hoped for the former.

Around this time, I began receiving requests to act as an expert witness for defense attorneys intent on challenging the laws against marijuana. Most state laws treated marijuana as a narcotic, which it is not. Narcotics are constituents or derivatives of opium that act as sedatives and analgesics. The cannabinoids in marijuana are unrelated chemically and pharmacologically to opioids. The penalties for the possession and sale of narcotics seemed to me excessively harsh for opioids, let alone for marijuana. Being a regular user myself, I was all for efforts to decriminalize it and was happy to do what I could for those who ran afoul of the law.

My research had shown that smoking pot has few physiological effects. I’d found that it causes a moderate increase in heart rate, does not lower blood sugar (often invoked as the reason users get the munchies), and does not dilate the pupils as cocaine, speed, and other stimulants do. (In some of the cases in which I testified for the defense, cops cited dilation of pupils as probable cause for suspecting the defendants had been high on weed. This I could disprove easily.)

On the witness stand I was regularly asked how I could tell that someone was high on marijuana. My answer has always been that you can’t, unless the person volunteers that information. Pot often makes a person’s eyes turn red, but this can also be caused by eye fatigue, allergies, and other common irritants. Novice users may become giddy or withdrawn; experienced users are likely to go about their business without exhibiting any obvious changes in behavior. Law enforcement agents, mental health professionals, and antidrug crusaders did not want to hear this.

I found it so amusing that people with no experience of marijuana thought they could tell if someone was high on it that I resolved never to speak about it in public or testify about it in court unless I myself was stoned. (It was easy enough to smoke pot unobserved on the way to an event. Back then, few knew what it smelled like; people commonly described the odor as “sickly sweet.”) How satisfying it was, having just toked up, to state with authority that there is no way to know that someone is under the influence of marijuana unless they volunteer that information. Best of all was saying that while being cross-examined by a hostile prosecuting attorney.

Some of the prosecutors I encountered tried to discredit my botanical expertise by asking what they thought were tough questions: What’s the difference between a monocot and a dicot? What’s the biggest monocot in the world? They failed. I was able to hold my own during cross-examination. The lawyers I worked with told me that my appearance for the defense often helped to reduce sentences.

In 1977, I was asked to appear as an expert witness in a marijuana trial in Japan. The request came from Keiichi Ueno, who has prepared Japanese translations of many of my books and become a close friend. The defendant, Satoshi Fukui, was a young, accomplished sumi-e artist. (Sumi-e is a traditional form of brush painting with black ink.) He was also a countercultural hero with a following of long-haired, wild-looking hippies who played flutes and smoked pot constantly. Cannabis is well-known in Japan as a source of hemp fiber, but that kind of cannabis has very low THC content and causes minimal psychoactivity. It was not until the Sixties that Japanese hippies began smoking imported marijuana and hashish, which were strictly prohibited and regarded by most Japanese people as dangerous drugs introduced by foreigners. Fukui had been busted for cultivating marijuana in his backyard.

He maintained that he had done nothing more than scatter birdseed. At the time, birdseed sold in Japan contained viable cannabis seeds, and Fukui soon had a number of plants growing behind his house. The police, hoping to make an example of him, charged Fukui with violating the Cannabis Control Law. Friends persuaded him to challenge the law by arguing that marijuana was relatively innocuous, and, surprisingly, a court in Kyoto agreed to hear the case. Given that there were no Japanese cannabis experts, Fukui’s lawyer petitioned the court for permission to call me as a witness. He did not expect to succeed, because courts in Japan almost never allow foreign experts to testify, but permission was granted. In the end, Fukui was convicted but received a suspended sentence.

By the Eighties, cocaine had become a popular illicit drug in North America, and I began to receive requests to testify about it. Cocaine was also treated as a narcotic under most state laws, but convincing judges and juries that harsh penalties were unjustified was trickier than in the case of marijuana. Physiologically, cocaine is not as toxic as alcohol, but its behavioral toxicity and addictive potential are significant. Nevertheless, I appeared as an expert witness for the defense in a number of trials involving the drug. Although I had not studied it in a laboratory setting, I had done ethnobotanical research in Colombia and Peru on coca, the natural source of the drug, and I had observed many regular users of cocaine in the United States.

I’ve given expert testimony in many state courts, in federal court, and in one court-martial. I have a fond memory of testifying in a case in Brownsville, Texas. When the defense attorney finished questioning me, the state attorney began his cross-examination. After a few routine questions, he stepped closer to the witness stand and asked, “Isn’t it true, Dr. Weil, that Sherlock Holmes became addicted to cocaine and that it destroyed his career?” I was at a loss. “It is my understanding,” I answered slowly, “that Sherlock Holmes is a fictional character.”

“No further questions,” the prosecutor said.

The strangest trial I attended was an LSD case in the federal district court in New Orleans. The defendant, charged with selling 3,400 tabs of acid to a federal agent, claimed he was distributing a sacramental substance that was a safer alternative to other drugs. No one expected the court to entertain his claim.

Richard Sobol, a lawyer I hung out with in the D.C. area in the early Seventies, had moved to New Orleans to work on civil-rights cases. In 1971, he called to tell me he had taken the acid supplier on as a client and was fascinated by him. The man looked like Jesus, he said, and distributed a pamphlet called Free LSD. In weekly meetings at a city park, he and others would take LSD and attempt to achieve group consciousness and manifest peace and love. With their spiritual guide facing prosecution as a major drug trafficker, they began to direct collective mental energy at the judge appointed to hear the case. Richard asked me to come to New Orleans and be an expert witness for the defense.

The courtroom was packed with spectators, including a large contingent of the defendant’s fellow LSD enthusiasts. One of them, a young woman, came up to me as I was about to take my seat, gave me a warm smile, and said in a seductive voice, “Close your eyes and open your mouth!” As I did so, she placed a tiny tablet on my tongue. “Swallow and join us,” she told me, and I did.

Thirty minutes later, during preliminary motions from lawyers for both sides, I came on to the drug. It must have been a substantial dose, because I was soon on a strong acid trip that would last the whole day.

The first thing I realized on my trip was that no one wanted to be there. Everyone—from the lawyers to the clerks to the judge and the defendant—would rather have been elsewhere. I watched transfixed as individuals morphed into archetypes. The judge became The Judge, cloaked in authority. The prosecuting attorneys, wearing American flag pins, moved like robots. I saw how bottled up they were, how disconnected from their feelings. A police officer took the stand to describe how he arrested the defendant after pulling a car over. When asked what happened next, I remember him saying, “Two Caucasian males exited from the vehicle.” What kind of unnatural talk was this?

The government’s first expert witness was a researcher from Tulane who had given monkeys high doses of LSD, then examined their brains for abnormalities. He claimed to have found plenty. Except he had no way to prove that LSD caused the abnormalities; they might have been pre-existing or artifacts of his method of preparing the tissue. Still, he insisted that the drug was the culprit. I was repelled by his cruelty to animals and saw the logical flaws in his testimony.

Next came a psychiatrist who dealt with drug users and had seen the “psychic damage” LSD could cause. According to him, acid made people psychotic and out of control, likely to hurt themselves and others. It scrambled the mind of anyone foolish enough to try it. To my own very clear mind it was obvious he did not know what he was talking about.

When the defendant took the stand, looking more messiah-like than ever, I had a sudden insight about the courtroom process. The collective attention focused on a witness makes it possible to tell if that person is speaking truthfully. I saw a blaze of white light around the defendant as he described his LSD-induced spiritual awakening. I knew he was telling the truth about it and about the sense of mission that he felt. He genuinely believed that it was his duty to make that experience available to others by providing them with what he considered to be a sacramental substance. He honestly felt that he was helping people. He was neither psychotic nor out of control. I thought he held up well during a tough cross-examination.

The defense called me to refute the testimony of the government’s experts and support the contention that LSD can have positive effects. I was feeling those effects strongly as I answered Sobol’s questions about the toxicity of the drug (negligible), its psychological dangers (significant but totally manageable) by attending to dose, set, and setting, and its potential to accelerate spiritual development (great). I spoke—or anyway, I think I spoke—forcefully, succinctly, and with authority.

Then I felt compelled to ask the judge permission to speak directly to the court. “I mean this with no disrespect,” I said to him, “but you should know that for the entire time that I have been on the witness stand I have been under the influence of LSD.”

There were gasps from the courtroom. Sobol’s jaw dropped. The judge merely nodded.

Remarkably, my admission was not reported in contemporary news coverage of the trial. Nor have I ever been asked about it since.

In my book The Marriage of the Sun and Moon, I describe the preparation and use of coca leaves by indigenous Amazonian tribes in southeastern Colombia. In the Seventies and early Eighties, I made a number of visits to a Cubeo village deep in the Amazonian rainforest. I would get there by speedboat from the town of Mitú, on the Vaupés River. The village consisted of no more than ten well-built thatch houses grouped around an open plaza. There was also one large maloca, a communal dwelling where several families had hammocks and cooking fires and where people gathered for meetings and nighttime fiestas. A dense forest surrounded the village, with a few cleared areas for the cultivation of yuca, chili peppers, bananas, and coca.

Many tribes use coca in a distinctive way, preparing it fresh by picking and then toasting the leaves, pulverizing them in a wooden mortar, mixing them with the ashes of the leaves of a jungle tree (which supply alkalinity to promote extraction of active compounds), then sifting the mixture through a muslin sack to yield a tasty, gray-green powder with the consistency of flour. All of the Cubeo men and some of the women consumed this powdered coca, working it into moist lumps in the mouth and letting it dissolve slowly.

Cubeo men fished every day, hunted, and harvested coca plants; women worked to cultivate and prepare yuca, first extracting its toxic juice, then turning it into a thin, dry bread or into chicha, a mildly alcoholic fermented beverage.

Cubeo fiestas happened quite regularly whenever I was there, possibly because of my presence. They began in late afternoon, when people would sit on benches under a ramada and drink a lot of chicha, both the ordinary kind and one I found much tastier, which was made from pupuña, the starchy orange-fleshed fruit of the peach palm. After a number of gourds of chicha and spoonfuls of coca, some of the men would begin to play carrizo flutes. Soon several men would link arms and dance back and forth in a line, the women later joining in. These very agreeable events went on for several hours until the night sky was bright with stars and people drifted off to their dwellings. When there was no fiesta happening and I was not interviewing Cubeos or watching them prepare food, drink, and coca, I mostly lay under a net in a hammock, dozing or reading, trying not to mind the constant heat and humidity, hiding out from the innumerable biting sand flies that abounded from dawn to dusk and attacked any area of exposed skin.

On several occasions I went to the village by myself; once I visited with a Colombian couple, filmmakers who wanted to make a documentary about native uses of natural drugs, and on one trip I brought a friend along. Steve Shouse, who was interested in Native American cultures and religions, had backpacked with me in Arizona; he had never been south of Mexico.

A problem I wrestled with each time I went was what to bring as gifts. One day I had a sudden inspiration. Light sticks had just become available—the plastic wands that when activated emit bright neon light for hours. They first appeared in camping supply stores, long before they became popular at clubs and raves. I bought boxes of them and packed them for my next trip.

Steve and I spent several days with friends of mine in Bogotá, made last-minute preparations for our adventure, then took a colectivo taxi across the eastern range of the Andes to Villavicencio, a frontier town that was the jumping-off point for travel farther east. From Villavicencio we caught a small doorless cargo plane to Mitú and spent a restless night in a hostel, kept awake by violent thunder and torrential rain. The next morning was clear, and before the heat and humidity became unbearable, we found a boatman to motor us upriver to the Cubeo village.

We arrived at midday. The Cubeos I knew welcomed us warmly and showed us to a vacant hut where we strung up our hammocks. The afternoon was too hot to do much of anything except avoid the sand flies and wait for sunset. Near the equator, evening comes quickly once the sun is down. Unless storm clouds build, the sky is soon black, and with no light pollution, the display of stars is dazzling. Even before it was dark, the Cubeos got ready to celebrate our arrival. They invited us into the maloca and plied us with chicha and coca. I distributed cigarettes. Soon the only illumination came from several cooking fires. The main sound was the buzzing of cicadas.

After more chicha and coca, the men began to play their flutes, at first seated on wooden stools, then standing, then linking arms and dancing. After a time, women ducked in between the men, joining the dance, and then my companion and I were pulled into the line. The simple repeated flute melody, the stomping of feet on the earthen floor, and the flickering firelight cast a hypnotic spell over us, intensified, I’m sure, by the agreeable combined effects of chicha and coca.

During a pause in the dancing, I got out one of my light sticks and bent it to break the capsule inside, allowing the chemical solutions to mix and do their magic—instant luminescence that created a brilliant glowing wand, all the more impressive in the mostly dark maloca. Gasps of surprise came from many of the Cubeos; a few approached it warily. Very soon they were enchanted. They were familiar with the bioluminescence of fireflies, but had never seen man-made cold light, a beautiful light that did not flicker. They touched the light stick, asked to hold it, passed it around, admired it.

Then one of the men managed to open a light stick and pour some of the luminescing liquid into the palm of his hand. Others gathered around to marvel at the sight. Several people dipped their fingers in the fluid and applied it to their skin.

Many Amazonian people, men much more than women, adorn themselves with paint. The men of some tribes spend hours decorating themselves and others, checking their work, and admiring the effects. Cubeo men apply face paint sparingly on special occasions, using natural red, yellow, and black pigments. Restraint was thrown to the wind, however, when they got their fingers into this fluid that glowed a brilliant yellow-green. With whoops of excitement they began decorating themselves, one another, and us. Soon our faces and torsos were striped and dotted with cold light. Special attention was given to my bald head, always a source of fascination to Amazonian tribal peoples, who, as far as I know, never lose their hair.

The dancing that followed was like nothing I’d ever seen. Men and women formed a line, right hands on right shoulders, and we all stomped and snaked our way around the maloca to the accompaniment of flutes and rattles. There were occasional breaks for more chicha, coca, and body painting. We even applied it to our feet, which enhanced the experience, and we continued dancing until most of us collapsed on the ground, breathless and spent. At some point, Steve and I crept out into the night and crossed the plaza to our hut and hammocks, where we slept in later than usual.

With the new day came a stream of Cubeo men, eager for commerce. What would we like in exchange for the boxes of light sticks? Cans of coca powder? Fish? Hammocks? Several men tried to get exclusive distribution rights, promising us all sorts of things in return. Each tried to convince us that he was the only member of the tribe who could be entrusted with the goods. In the end, we distributed the sticks equally and then began the long journey home.