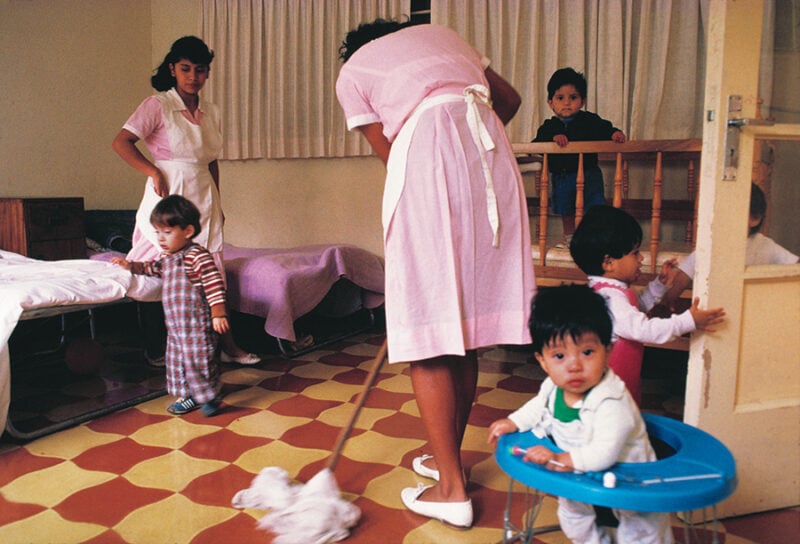

Childcare workers with children waiting for adoption, Guatemala, 1989. Photographs by Susan Meiselas © The artist/Magnum Photos

Discussed in this essay:

Until I Find You: Disappeared Children and Coercive Adoptions in Guatemala, by Rachel Nolan. Harvard University Press. 320 pages. $35.

In May 1982, Blanca Luz López entrusted her son, a toddler, to a full-time caretaker in a poor neighborhood of Guatemala City. This was a common arrangement for working mothers, like López, whose long hours prevented them from assuming themselves the responsibilities of parenting. She visited her son when she could, and then, one day that next February, he wasn’t there. The caretaker said she had sent the boy elsewhere “for his greater safety,” and gave López an address. López went to the house, and a woman there told her that the boy would be returned to her at a piñata party so that he could be given a proper goodbye.

When López and four other people—three adults and a child—arrived for the party, they were shown in, offered a bottle of liquor, and then set upon by a group of attackers with knives. All four adults, including López, were murdered, and the child was kidnapped. The assailants had already shuttled López’s son out of the country, and the other child was never seen again. To this day, neither has been found.

Before Guatemala outlawed foreign adoptions in 2007, one in a hundred children born there was adopted internationally. The country was second only to China in the number of children being sent abroad, yet Guatemala had a population of about thirteen and a half million people, roughly one one-hundredth of China’s. Rachel Nolan, in her detailed and heartrending first book, Until I Find You: Disappeared Children and Coercive Adoptions in Guatemala, uses years of research to show the way that a country destabilized by war can invite merciless profiteers to break apart families such as López’s and allow others overseas to reconfigure them according to their own desires. For the three decades between 1977 and 2007, Guatemala allowed lawyers to match children with foreign families, with minimal oversight from a court. What happened in Guatemala, along with similar scandals in Romania, South Korea, and Peru, inspired the creation of the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption in 1993. The treaty now governs the way more than a hundred countries conduct adoption across national borders.

Nolan has written, in these and other pages, on Latin America and its literatures for years, blending original reportage with detailed history and astute analysis. She often drops anchor in situations that have been reduced, especially in the United States, to talking points, such as the malefic “cartels” of Mexico. With Until I Find You, Nolan uses the adoption scandal to, among other things, distill the complexities of the Guatemalan Civil War of 1960 to 1996. This was a less evenly matched conflict than generally implied by the term “civil war.” Rather, it consisted of the government slaughter of leftist and Indigenous insurgents, as well as thousands of civilians. (The conflict had its origins in a CIA-backed coup in 1954 and was prolonged by U.S. support for Guatemalan governments.) Nolan dissects the country’s recent history without succumbing to the sanitizing impulse of much academic prose, and without overdramatizing what could easily be maudlin: babies whisked away from families and disappeared into distant lands. “While often initiated with the best of intentions in wealthier countries,” Nolan writes,

international adoptions were the result of immiseration in sender countries, where they were bound up in violent conflicts over politics, local racial divisions, and enforcing often misogynistic ideas about the role and place of women.

And some, of course, did not have the best of intentions.

In the United States today, if you want to adopt a child using the Hague Convention process, you must choose an accredited adoption agency and have your home inspected by a social worker. Then you file an application with United States Citizenship and Immigration Services and prepare a dossier of documents for the foreign country. Only after taking these steps can you be matched with a child. Once you match, you apply again to USCIS for provisional approval to go ahead. If approval is granted, you begin additional legal proceedings in the child’s country of origin. Finally, you are invited to pick up your child in their home country and report to the local U.S. Embassy for a visa interview, which, if successful, will allow you to bring the child to the United States. The process can take one and a half to four years and can cost between $20,000 and $50,000. (By contrast, adopting a child through the U.S. foster-care system can cost as little as $2,700.) Birth parents must relinquish their children freely, and they cannot be paid.

From 1999 to 2007, about thirty thousand children, many of them Indigenous or from families in extreme poverty, were adopted out of Guatemala—with more than three quarters of those kids going to the United States. Adoptions ramped up after the 1976 earthquake—or “classquake,” as Nolan and others refer to it—which killed an estimated twenty-three thousand people in the country. The response to the disaster “laid bare social inequalities and prompted coverage of an orphan crisis,” she writes. In its aftermath, the Guatemalan state collapsed, and international humanitarian agencies, many of them evangelical Christian in character, stepped in. One of the proposed solutions to the huge number of orphans was a law that privatized adoptions.

An Indigenous farmer, Chichicastenango, Guatemala, 1981

While state-run adoptions took years to complete, private ones could be wrapped up in a few months. Costs for adoptive parents grew from a few thousand dollars in the Eighties to almost $60,000 in the late Nineties, in today’s dollars. Lawyers earned $4,000 from a $20,000 international adoption, whereas birth parents were compensated the least: one Mayan Tz’utujil-speaking mother said that she was offered $40 and bus fare to give up her son.

“As foreign demand rose and the revolutionary notion of a child’s right to remain with their birth family was suppressed,” Nolan writes, “the principle of the best interests of the child was defined in a straightforward way: material wealth.” As with much of the Global South, permanent international adoption came to supersede older, informal modes of mutual aid. Among many Indigenous groups, personal struggles—including with childcare—are shared by the community. But coerced adoptions only accelerate the dissolution of existing support systems: a textbook example of how colonial logic disrupts perfectly functional societies. Blame for children being transferred abroad—if cast at all—almost always landed on mothers. They were often called madres desnaturalizadas, or “denatured mothers,” by journalists.

Enabled by privatization, lawyers began working with baby brokers, or jaladoras (“pullers”), who were paid to locate adoptable children. A jaladora would spot poor, typically Indigenous pregnant women “at home, at bus stops, in hospitals, or in marketplaces” and sell them on giving up their children. Some jaladoras, Nolan writes,

carried photo albums and flipped through them with pregnant women, showing them Guatemalan boys and girls in comfortable middle-class families abroad.

One photo of an adoptive family in America featured wall-to-wall carpet and a piano. As if they were something out of the Brothers Grimm, some pregnant women were subjected to casas de engorde (“fattening houses”), where jaladoras would keep them until the adoption was finalized.

Justifications for these tactics, as well as less villainous ones, varied. As Susana Luarca Saracho, a lawyer who worked with jaladoras and later went to jail for child trafficking and falsifying adoption papers, put it to the New York Times in 2006: “Which would a child prefer, to grow up in misery or to go to the United States, where there is everything?” Yes, there was and is instability in Guatemala, but there is also culture, language (twenty-two Mayan tongues, at last count), family—the implied “nothing” that nonetheless makes a place a home.

Private adoptions rose during Guatemala’s most violent years. Nolan’s book contributes to the historiography of the multidecade conflict, which has already been the focus of some excellent scholarship by such specialists as Greg Grandin, Victoria Sanford, and Stephen Schlesinger. But the war and the country remain poorly understood in the United States. About two hundred thousand Guatemalans died in the conflict. An estimated forty-five thousand people were also disappeared, about five thousand of whom were children. At least five hundred—which Nolan thinks is a “substantial undercount”—of the disappeared children were put up for adoption. And yet, it would be wrong to count, since each child “is not just an individual, but surrounded by a web of family and community,” as Nolan writes. “Numbers fail to convey the tearing of the entire social fabric around the forced disappearance of a child.”

I can attest to those tears in the fabric. My great-uncle Toma was disappeared from a small central Romanian village in the 1950s, when he was a teenager. All my life I have listened as my family members talked around the event but found themselves pulled in, as if by an emotional black hole. In our case, at least, there was a reunion: a decade after Toma’s disappearance, he came back. In the intervening years, he’d been jailed, tortured, and forced to work in grueling conditions, but he had survived. Though my grandmother, his sister-in-law, now lives in rural Ohio, she is still scared of the Securitate, the secret police force, which was disbanded in 1989. She was also adopted as a child and didn’t know who her biological mother was until she was nearly ten; she met her biological father only once, as an adult. As in Guatemala, the accumulation of steep economic inequality, political persecution, and forced migration affected many Romanian families. Mine, though split, has stitched itself back together. Still, when I look at my four-year-old son, I sometimes remember a rupture I never lived.

An adoption center in Guatemala City, 1989

Nolan’s book centers on Guatemala, “but in its broadest strokes,” she writes,

the story resembles that of many countries where Indigenous children have been separated from their families, where people have preyed on birth mothers to profit from commercial adoptions, or where families have struggled to keep and raise their children in the face of mass violence, untenable economic pressures, and unfreedom for women.

Native Americans in the United States, First Nation kids in Canada, and Aboriginal children in Australia, not to mention the children who were disappeared in Nazi Germany, Francoist Spain, and Argentina during the 1976–1983 dictatorship, have been subject to illegal adoption, but Guatemala was notable for the way, as Nolan puts it, that “colonial and Cold War violence marched lockstep.” When, in 2013, the country’s former dictator Efraín Ríos Montt was tried for genocide in Guatemala City, adoption records were used as part of the case against him. Since 1948, “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group” has been one of the United Nations’ criteria for classifying crimes as genocide. More than three decades of violence not only increased “humanitarian” adoptions in Guatemala, but set off a wave of emigration that continues today.

While extremely high unemployment in the Eighties accelerated a trend of Guatemalan men fleeing north on their own, whole Guatemalan families now migrate, and children increasingly attempt the journey alone. Though they may no longer be spirited away by “philanthropic” institutions, they are now forced out by a perilous combination of extreme poverty, climate change, and violence. In December 2018, two Guatemalan children, eight-year-old Felipe Gómez Alonzo and seven-year-old Jakelin Caal Maquin, died while in U.S. custody. In 2022, according to the New York Times, more than sixty thousand children from Guatemala crossed the U.S.-Mexico border without their parents. Many end up with relatives in the United States, but others land with unrelated sponsors. Little is known of their circumstances.

After years of teetering on the brink of state collapse, there has been recent cause for hope in Guatemala, with the election of Bernardo Arévalo as president last August. (One of his opponents in the presidential race, Edmond Mulet, was arrested in the Eighties for falsifying adoption paperwork.) Arévalo’s father, Juan José Arévalo, served from 1945 until 1951 as the country’s first democratically elected leader. Arévalo’s mother, Elisa Martínez Contreras, instituted programs that prioritized the rights of families and communities. If Arévalo isn’t forced out by a judicial system seeking to undermine him at every turn, he may be able to continue reuniting Guatemalan families—as well as the country as a whole. On January 14, the day he was due to be sworn in, reactionary lawmakers attempted a coup, delaying his inauguration by nine hours. Arévalo took office with the support of the Biden Administration, whose State Department officials had spent months strong-arming business leaders and had imposed visa restrictions on two thirds of Guatemala’s Congress. Arévalo inherits a country in which legal adoption routes are still closed to foreigners and abortion remains illegal, with the sole exception being to save the life of the mother. Same-sex marriage is outlawed, and LGBTQI people routinely suffer persecution. The lives, rights, and identities of Guatemalan children remain in peril.

And so it’s not surprising that many Guatemalans want their children to grow up in the United States. Once asylum seekers get to the U.S.-Mexico border, they are faced with a choice: wait months for an official appointment or submit themselves to human smugglers. For those families who decide that languishing in a border town, trekking the desert, or fording the river is too dangerous, there’s another option: sending their children to the United States alone. A slew of anti-immigrant policies, created by Trump but hardly disturbed by Biden, has made it more difficult for many asylum seekers to claim protection. But border officials will take unaccompanied minors into custody and begin processing their claims immediately. The setup has created an impossible bind: if parents relinquish their children, knowing they might not see them again, they may save their lives. Consequently, from September to November of last year, the number of minors showing up in Nogales, just one port of entry, almost tripled from 50 to 140, Pedro de Velasco, an advocate for migrants’ rights who works at the Kino Border Initiative, told me in February. I’ve spoken with a number of families, some from Guatemala, who’ve struggled with this decision—if “decision” is the right word in such a situation.

Lawsuits have forced the U.S. government to try to reunite some of the families they pulled apart during the family separation crisis, and they have returned more than seven hundred children to their parents. But reunion, as one can see from the example of Guatemala, is not the same as repair. “I felt like I was foundationless,” said Gemma Givens, who located her Guatemalan birth mother at the age of twenty, after being brought to the Bay Area at four months old. “I was floating, or I was a ghost. . . . Whose face do I have?” One Guatemalan organization, La Liga, has helped at least 527 families find children who went missing during the war. Thousands more remain in the dark.