Illustrations by Pep Montserrat

Jacob Angeli-Chansley, the man the media has dubbed the QAnon Shaman, had been released from federal custody six weeks before when we met for lunch at a place called Picazzo’s, winner of the Phoenix New Times Best Gluten-Free Restaurant award in 2015. Despite a protracted hunger strike and 317 days isolated in a cell, Jacob’s prison sentence of forty-one months for obstruction of an official proceeding on January 6, 2021, had been shortened owing to good behavior, and he was let out about a year early on supervised release.

It took some doing to get him to sit for an interview, as Jacob is wary of what he calls Operation Mockingbird, an alleged CIA-sponsored effort begun in the Fifties to use mass media to influence public opinion. Jacob believes that people like me are the tools of the Mockingbird operation, of the deep state, international bankers, pharmaceutical cartels, and corporate monarchies that control the world. People like me believe in medicines that are addictive drugs, in food that is poison, in environmentalism that is ecocide, in education that is ignorance, in money that is debt, in objective science that is not objective. “People are brainwashed by the elites and their propaganda networks,” he said. “Mass hypnosis, bro.”

He had agreed to meet with me on a number of conditions, including:

1. That I mention Dr. Royal Raymond Rife, the American inventor of an oscillating beam-ray medical technology that, according to Jacob, is a cure for cancer that has been quashed by the government, the military, and pharmaceutical giants; and

2. That I call attention to the existence of a clean, free, wireless, and renewable energy source powered by the earth’s magnetic field that was discovered by Nikola Tesla but suppressed by the government because such a technology would make the existing energy grid obsolete, and thus threaten the rule of the globalists and their corporate monopolies.

Jacob believes he has been sent to earth to combat wicked forces such as Warner Bros. and MGM. He believes in the clear and present danger of a global ring of slave-trading, adrenochrome-swigging Clintonistas. He would also like to lift the ban on psilocybin mushrooms. And he’s been doing the work for a long time—for “millennia,” he told me. “I have reincarnated on this planet numerous times throughout the ages.”

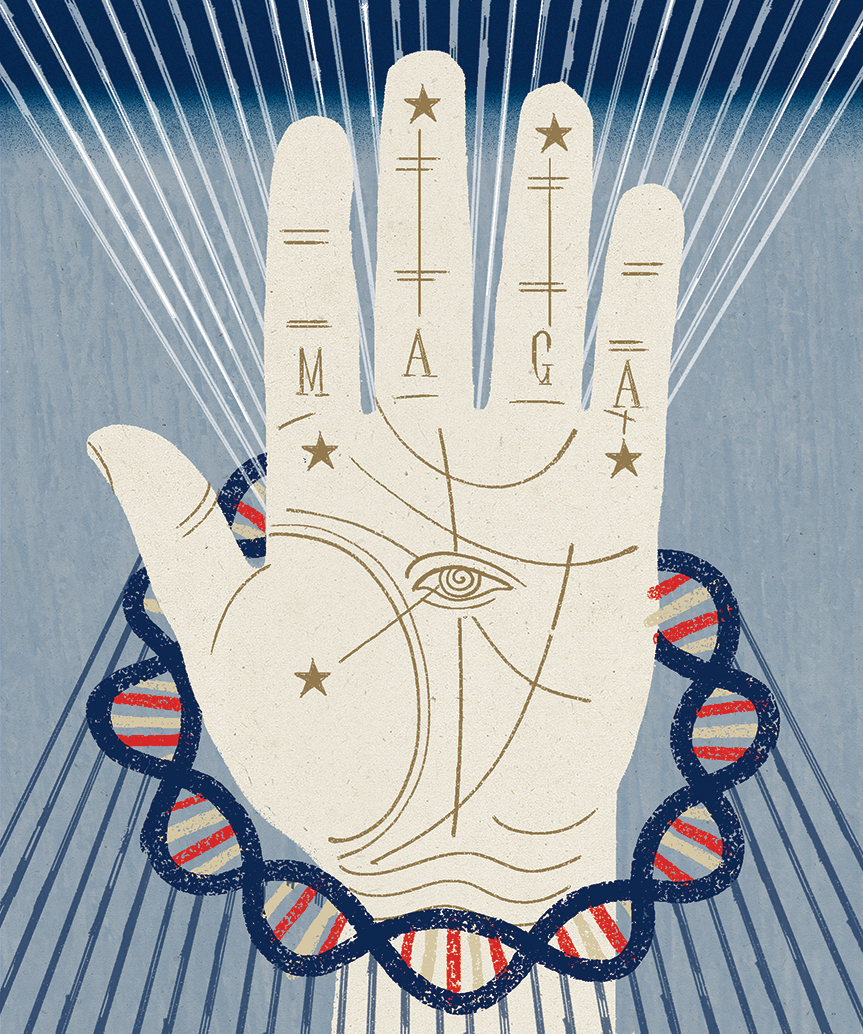

Jacob is as apt to paraphrase Shirley MacLaine as WikiLeaks Vault 7 or Alex Jones, which is why I had reached out to him. He is Exhibit A of the widely reported observation that MAGA, QAnon, and the broader conspiratorial mishmash draw substantial support from the consciousness-raising, om-chanting, sound-healing, joint-toking, crystal- and chart-reading crowd, the long-haired hippies who half a century ago were lumped together with the fellow travelers of the left, but have been reincarnated two generations later as pivotal elements of the Trump coalition. Jacob and his cosmic vibrations epitomize that political reversal. Perhaps, I thought, there was something in his belief system that could explain how the self-evident truths that guided the foundation of American democracy had lost their way in the wilderness.

I figured the tattoos would be a good place to start. As he was perusing Picazzo’s menu, I mentioned the marks on the backs of his hands. They were planets, pyramids, and runes, he said—the alphabets native to early Germanic and Norse peoples. The massive dark blots on his shoulder took six and a half hours. “My reality—what I thought was reality—was ripping at the seams right in front of my closed eyelids,” he said, recalling the ordeal. “I was seeing the quantum particles.”

He was also tripping on mushrooms.

Thor’s hammer he mostly did himself. “It would have looked a lot better,” he told me, “but I got locked up.” The tattoos on his shoulder, Jacob said, “represent manhood.”

The bricks that adorn his arms are a result of his dad having introduced him to the psychedelic space-rock band Pink Floyd and their wildly successful stoner opera The Wall, which tells the story of a fatherless musician who can perform onstage only after a drug injection leads him to believe he is a fascist dictator. (Roger Waters, mastermind of the production, has demonstrated his own penchant for parading around onstage in Nazi-style regalia, flanked by men dressed like storm troopers.) Jacob explained that the wall of bricks was a means of “healing from all the mental and emotional pain of growing up with an alcoholic dad who I loved very much and I know loved me.”

His biological father spent most of Jacob’s youth in jail and played no role as a parent. His stepfather, whom he calls his dad, committed suicide.

Friedrich Nietzsche once said that “when one has not had a good father, one must create one.” Carl Jung ratified the idea of the fantasy father in 1919, when he labeled the concept an “archetype,” by which he meant a mental compendium of mythic, legendary, and fairy-tale fathers all wrapped up into one enormous daddy issue.

Jacob, who was born in 1987, came of age in the wake of Robert Bly’s Iron John, a book published in 1990 about modern man’s alienation from heroic male archetypes that spent sixty-two weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and was a seminal work of the mythopoetic men’s movement. Like Jacob, Bly served in the Navy. Like Jacob, Bly’s father was an alcoholic. Like Jacob, Bly was interested in Old Norse mythology—in particular, the epic tales of the principal Norse god Odin, who, in order to gain mystical knowledge, subjected himself to nine days and nights of torture. He lanced himself with a spear and hung upside down from Yggdrasil, the cosmic tree that connects the nine realms of the universe, a tattoo of which lies over Jacob’s heart.

In the era of Iron John, “manosphere” membership required bongos, sweat lodges, hugging, weeping, and throwing spears at boars. Today, it’s about getting buff, buying liver-enzyme pills online, and keeping a paleo diet. Still, Bly resonates throughout the language and philosophy of Jordan Peterson, Joe Rogan, Tony Robbins, Andrew Tate, Josh Hawley, and other prophets of the modern men’s-rights movement.

In 2018, under the pseudonym Loan Wolf, Jacob self-published his own version of Iron John, called Will & Power: Inside the Living Library, whose hero retreats to the wilderness and stumbles upon an alien from the planet Ularu who looks like a hairy Sasquatch, has telepathic powers, and does a lot of yoga. This steely Übermensch goes by the name E-Su and teaches the hero to battle the corruptions of the world. We discussed the novel’s scenes of violence, and Jacob told me that there had been many powerful ancestors in his bloodline, and that in each of his thousands of previous lives, he and they had fought the good fight.

I nodded, and we sat in silence for a while. A waiter appeared, smiling in a vague, embarrassed sort of way. He seemed to have recognized Jacob and was ready to stand at attention.

But The Shaman’s thoughts had roamed far from the realm of gluten-free food. “The most evil things happen when a person believes that they are anonymous, when they’ve covered their face,” he mused after some time. “Whether it be with war paint, or whether it be with a mask.” Which struck me as odd, because at the Capitol on January 6, Jacob had painted his face. He had covered his head with a coyote-tail headdress and topped it off with buffalo horns. Holding his staff and megaphone, he sat his ass down in the presiding officer’s chair.

Now he looked me square in the eye.

“You’re paying, right?”

For the record, The Shaman ordered his pizza topped with artichoke hearts, basil, chicken, and mushrooms.

In court, Jacob’s lawyer told the judge that his client would not kill an insect, that he was picked on as a child and bullied as a teenager. After high school, he joined the Navy and found himself aboard the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk, a floating apocalypse-in-waiting, bristling with surface-to-air missiles, Super Hornet fighter jets, Prowler radar jammers, and Seahawk helicopters. It was the same ship aboard which John Frankenheimer filmed scenes for Seven Days in May, the 1964 black-and-white classic in which Kirk Douglas plays Colonel “Jiggs” Casey, who uncovers a plot against the United States government masterminded by the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It was the first movie of its kind, ushering in what became a standard in Hollywood thrillers after the Kennedy assassination: the deep state conspiracy.

About six months into his assignment, the ship psychologist diagnosed him with schizotypal personality disorder, an incurable condition characterized by social isolation, limited reactions to social cues, and sometimes a penchant to dress unusually. He received what the military calls a “general discharge, under honorable conditions,” in 2007, and returned to his mother’s house in Phoenix.

The living room here has an ornamental equine vibe—lit by a horse lamp, wall adorned with images of horses—except for the bookshelf, where what might have been a cowboy hat has been replaced by a Trump hat. Martha Chansley doesn’t subscribe to cable television. She believes that the buffalo is a “mystic” animal. When a reporter and camera crew from FOX 10 Phoenix descended on her house after her son had been taken into custody, she noted another mystical bond, this one with Donald Trump: “We are a part of him, and he is a part of us.”

“My mom was always kinda into woo-woo,” Jacob admitted.

After being discharged from the Navy, he remembered how he had once happened upon a CD in his mother’s car. The plastic case showed a bald and bearded hippie who had been dismissed from his psychology assistant professorship at Harvard because of his research on psychedelic drug therapies.

“I was like—oh, okay, that’s interesting.”

What The Shaman had stumbled across was a set of lectures given by Timothy Leary’s colleague Richard Alpert. Four years after his dismissal from Harvard, Alpert had traveled to India and changed his name to Baba Ram Dass. Four years after that, he published a book called Be Here Now, which sold two million copies and became a counterculture bible for Steve Jobs, Wayne Dyer, and George Harrison.

“I was awestruck,” Jacob said.

The Ram Dass lectures took their place in his library of unorthodox thinkers, which had long embraced Ralph Abraham, a professor of mathematics at UC Santa Cruz, who was not only an expert on chaos theory and psychedelic shamanism but had spent a good deal of time living in a cave in the Himalayas. Abraham credited his use of the psychedelic drug DMT with his ability to see the connection between numbers and Logos.

Jacob discovered Terence McKenna, widely regarded as the “intellectual voice of rave culture.” McKenna was an ethnobotanist and mystic who read Carl Jung at the age of fourteen and later recorded hundreds of hours of lectures on topics that range from transhumanism to the so-called stoned ape theory of human evolution, which posits that one hundred thousand years ago Homo erectus became Homo sapiens by eating magic mushrooms.

Jacob also became enthralled by the man often called the “Godfather of the New Age,” Carlos Castaneda, who wrote about a shaman named Don Juan who ate peyote, talked to coyotes, and could enter “a separate reality.” As Castaneda continued writing, however, ultimately publishing a dozen books and selling many millions of copies, scholars reached a consensus that he had made the whole thing up. Don Juan was fake news.

But even if the accusations against Castaneda about Don Juan were true, contended Jacob—“that he’s not really a brujo, not really a sorcerer or a shaman, or that Don Juan’s not real—does that change the truth?”

I said nothing. The Shaman sipped his ice water.

“Dude,” he continued, “if I were to tell you all of the stories, all of the paranormal experiences that I’ve had, the UFOs that I’ve seen, the strange synchronicities—you know, Carl Jung synchronicities, the strange synchronicities that are of a divine nature very similar to divine providence—we’d be here for hours.”

As it turned out, we did sit there for hours. As Jacob had tweeted several weeks earlier:

The ether is filled with ideas! Ideas which are frequencies of energy that exist within the larger fractal sacred geometric pattern called the Unified Field or God, Carl Jung called it the Collective Unconscious.

Carl Jung’s great ally turned rival, Sigmund Freud, proposed a model of the human psyche that acted much like a machine—repression and projection as twin pistons in the psychic engine. Freud’s mechanistic sex drives and death drives would eventually please the psychoanalytic establishment, but it was Jung who would win the war of woo. While Freud had been consigned to dry debates within the New York Psychoanalytic Institute, Jung’s theory threw open the door to the New Age less than a decade after his death in 1961. His ideas went well with paisley prints, black lights, and sitars. Cosmic codes of harmonic convergence became the sort of conversation starter that could blow someone’s mind between sips of hippie juice at a Joplin concert—not to mention the thriving trade they sparked in crystals, hypnosis, meditation, numerology, palmistry, tie-dye, yoga, and all things unicorn.

When we go to Big Sur to soak naked in a freshwater pool overlooking the Pacific in an effort to explore “superhumanism, the survival of bodily death, extraterrestrial intelligence, and more” (straight from the Esalen Institute’s website), it is Carl Jung we channel. When we pop ketamine and puke ayahuasca, it is to Jung we owe our faith in the great synchronic woo.

“Our DNA and our brains are like antennae,” Jacob said to Alex Jones on his podcast The Alex Jones Show. “Our thoughts and our emotions are electromagnetic frequencies.”

“Like the Force of Star Wars,” agreed Jones. “This is a real thing.”

Were all conspiracy theorists Jungians in disguise? And how in the cosmic world had the Zurich School of analytic psychology become entangled with Donald Trump?

In 1902, Jung received his M.D., writing his dissertation On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena, which linked medical cases of epilepsy, multiple personality disorder, and somnambulism with séances, spiritualism, and divine metaphysics. It was the first of many works that would outline Jung’s belief in the convergence of the scientific and the supernatural, an idea that would eventually attract cultlike followers to his practice on Lake Zurich to explore the contours of the collective soul and reestablish an intimate connection with forefathers and fatherland, a relationship that had been diluted and usurped by those of a different phylogenetic inheritance—that is, by those of a different race.

The goal of this proto-Aryan philosophy was to purge a nation riddled with decadence, drug addicts, and degeneracy—the bloodsucking horror that was draining the vitality of European civilization, typified by the dark vision of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which appeared in 1897 and reached a cinematic representation in the 1922 German film Nosferatu, in which the vampire was given stereotypical features of a Jew.

Scholars have observed a wide swath of such early-twentieth-century German protofascist life-energy movements, and have labeled the phenomenon völkisch. Much like MAGA, the term is not easy to define. It implies a preference for rural, populist values as opposed to urban, elite ones, tradition as opposed to modernity, ethnic unity as opposed to diversity, nationalism as opposed to cosmopolitanism, all intertwined with a quasi-mystical nostalgia.

From the late-nineteenth century, völkisch ideas permeated German cults intent on discovering, in Jung’s words, “the age-old experiences of mankind that speak to him from his blood.” The Munich Cosmic Circle, for example, was animated by the belief that rationalism had caused the West to decline and that the only way out was a return to paganism. The Thule Society traced the Aryan race to a lost continent made of ice, while the Tannenberg Foundation, founded by General Erich Ludendorff, sought relief from the exigencies of modern life in the forests outside Munich by lighting bonfires and sacrificing horses in honor of Thor. Later in life, Ludendorff would assist in planning Hitler’s failed 1923 putsch in Munich.

The future führer, too, had völkisch leanings. Whenever he had the chance, he retreated to Haus Wachenfeld, his cottage in the Bavarian Alps that a 1938 issue of Homes & Gardens described as “set amid an unsophisticated peasantry of carvers and hunters.” His diet was plant-based. His closest advisers believed in astrology. He refused to ride in a zeppelin because no bird on earth had ever flown that way. He suggested that ships be propelled from the side, like the fins of fish. He believed that a previous age was dying, a new one about to be born. When the Nazis sought to repurpose the celebration of Christian holidays in the Thirties, embracing the paganism of their ancestors, they replaced St. Nicholas with the deity Odin, whose watchful eye was the sun. And when members of the Wandervogel, Germany’s first nationalist youth movement, communed in the sacred forest to feel the invisible tissues that linked German to German, to become one with the fatherland that had forged the Aryan soul, to be initiated into manhood by jumping over the campfire, and to despise the parasitic bastard races—they brought their guitars.

After January 6, a former high school classmate told the Daily Mail that Jacob had “changed a lot” since graduating. Clearly, the kid didn’t know Jacob. Because in his last year of high school, when asked to write a paper about what he wanted to be when he grew up, he had a ready answer:

My career of choice is to be a “master,” a Christ, a Buddha, or a Muhammad, whichever you prefer to call it. Now most people would say that there is no such career, and that a career is something you do for a living. Then I would reply with a smile and say, “What better living is there?”

Goals included “moving things with your mind, healing the sick, and rising from the dead.” Daily responsibilities “are nothing. That is the beauty of it; one can choose whatever one wants to create in one’s reality…. This is why every day of the master’s life is the best day of their life.”

Which would include January 6. When he reached the west side of the Capitol, he moved as if in a dream, gliding onto the Senate floor as if he were some fabulous pooh-bah whom no one had ever heard of yet. He ambled down the center aisle of the Senate chamber, past one hundred abandoned desks.

“Fuckin’ A, man,” he said.

“What then is the American, this new man?” J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur asked in 1782. At long last, Jacob provided the answer: He is a pagan straight out of central casting, a bro tripping on the hidden figures of the cosmos, a natural man convinced of his own self-evident truths, a hero ready to fight for his blessed fatherland, notwithstanding the fact that he still lived with his mother. Jacob stepped onto the dais, looked out on the sea of marble columns, and flexed his naked biceps.

A cop asked him to leave.

“I’m gonna take a sit in this chair,” he said. “’Cause Mike Pence is a fucking traitor.”

The Shaman penned his infamous prophecy of cosmic reprisal—it’s only a matter of time! justice is coming—and then stood. “Let’s all say a prayer in this sacred space,” he said. “Thank you, Heavenly Father, for gracing us with this opportunity—”

He stopped mid-sentence, removed his horned helmet, and began again: “Thanks to our Heavenly Father …”

One of the patients at the Burghölzli Hospital, where Jung worked in southeastern Zurich, suffered from a recurring hallucination that the sun had a penis. The man’s name was Emil Schwyzer, and at the age of twenty-five he believed he had been up for promotion at a London bank only to discover that he was instead being fired. For the next three days, he wandered the city streets in a daze, then put a bullet through his head—yet failed to kill himself. Delusions, depressions, paranoias, and various suicide attempts followed.

The bullet that presumably remained lodged in Schwyzer’s skull had left one eye virtually useless; he heard voices, couldn’t stick out his tongue, and was, in short, a twitching mess. Jung might have summarily dismissed the case as incurable “dementia praecox” (as he described it to Freud)—if not for the penis.

For years, Jung had been immersed in long-lost pagan rituals, from the worship of “dog-faced baboons” in Egypt to the esoteric philosophizing of Hermes Trismegistus. Now he recalled the Mithras Liturgy, which echoed Schwyzer’s hallucination “almost word for word.” How else could the patient have known about the ancient Persian cult of the sun, or the mystery religion it inspired in Rome, except if there were such a thing as inherited memory—that is, a collective unconscious? “The fantasies or delusions of … patients,” an early Jungian analyst declared, had been “paralleled in mythological material of which they knew nothing.”

As if the scales had fallen from his eyes, Jung now saw penis imagery in the rising and setting of the sun, in the death and rebirth of gods, and he concluded that worship of male heroes from Heracles to Elijah, alongside the rigid and indomitable rays of Helios and Horus, and other sun gods of all description and from all times, defined a condition not only embedded within the male ego, but within male egos dating back to time immemorial. Emil Schwyzer was not a run-of-the-mill psychotic. He was Solar Phallus Man.

Thenceforth, Jung sought to rediscover the “two-million-year-old” in each of us. He traveled to North Africa, Kenya, Uganda, India, and eventually to “a still lower cultural level,” that of the Pueblo Indians of the American Southwest—the native land of Jacob Angeli-Chansley. There, Jung encountered a man named Ochwiay Biano, also known as Mountain Lake. As Jung recalled in Memories, Dreams, Reflections, he and the Taos Pueblo leader conversed as “the blazing sun” rose “higher and higher.” As the conversation came to a close, Jung asked: Might not the sun “be a fiery ball shaped by an invisible god”?

“We are the sons of Father Sun,” Mountain Lake later said.

The ancient realm of the ancestral Pueblos stretched into the northeastern reaches of what is now Arizona, some 145 miles north of Phoenix. The native populations there have largely been exiled to the Gila River Reservation south of the city and west of the Superstition Mountains. Their traces remain in the faux sandpainting of eagle heads on street signs, the patterns of hotel wallpaper, an airport mural of a strange psychedelic bird with outstretched wings, the crushed gypsum diamonds and ocher triangles that adorn local fast-food joints.

Jacob’s Arizona is not the glittering land of real estate billionaires, nor is it the modernist enclave of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West, the golfing arcadia of Jack Nicklaus–designed courses, or the Hollywood getaway where Marilyn once sat by the pool of the Biltmore sipping a tequila sunrise. Jacob’s Arizona is the land of Barry Goldwater and Kari Lake, where Boogaloo Boys, Proud Boys, and Three Percenters carrying pitchforks and semiautomatic weapons descended on the county election office to “stop the steal.” Weeks before Jacob drove to the nation’s capital, he had been among that very crowd, where he was photographed, dressed in full shaman regalia, holding a hand-painted sign: q sent me.

But to get back to those quantum particles Jacob saw while tripping on mushrooms: The field of quantum mechanics emerged in Twenties Germany among a group of theorists that included a young math genius from Vienna whom Albert Einstein considered his “spiritual heir.” His name, Wolfgang Pauli, now colonizes the field, from Pauli repulsion and the Pauli equation to the Pauli group and Pauli paramagnetism. In 1930, Pauli postulated the existence of the subatomic particle now known as the neutrino, the most common variety of which spills down from the sun and penetrates the human body at a rate of roughly one hundred trillion per second. That same year, Pauli divorced his wife, mourned his mother’s suicide, and had a mental breakdown. All of which led to a life-changing decision: he made an appointment with Carl Jung.

Both Jung and Pauli believed that the solution to the riddle of his psychological turmoil resided in what the physicist called “the cosmic order of nature,” which like the bosons, fermions, quarks, and leptons that the new quantum theory contemplated, were not only invisible to the naked eye, but whose strange entanglements defied reason, prompting Einstein to famously dub them spooky.

Jung’s sessions with Pauli became the stuff of psychoanalytic legend. The Swiss doctor eventually interpreted hundreds of the Austrian physicist’s dreams, enough to fill the twelfth volume of Jung’s collected works, Psychology and Alchemy. The title of the volume was deliberate. “Alchemy is not only the mother of chemistry,” Jung wrote, “but is also the forerunner of our modern psychology of the unconscious.”

Alchemists had long searched for the drug that would open their minds to perfect knowledge—more along the lines of modafinil or Nooceptin than Klonopin or Lexapro, much less Cialis or Viagra. Their chymistry led them to toxic concoctions of copper and mercury and “sugars” of lead, crushed into “black pouder” and sublimated into “stinking smoke”—which the adepts breathed and tasted. Paracelsus himself synthesized diethyl ether, a sweet-smelling, highly flammable hallucinogenic anaesthetic that could induce euphoria. The concoction remained popular in the “ether frolics” of the nineteenth century. Long before the microdosers of Silicon Valley, long before Terence McKenna and Ram Dass and Timothy Leary—and before even Carl Gustav Jung and Wolfgang Pauli—the alchemists had discovered better living through chemicals.

Every old hippie, astrologist, shaman, and yogi already knows this: Everything is connected. Everything is full of meaning. Wisdom consists in decrypting the synchronicities. Thus: the world of the conspiracy theorist, in which a new respiratory virus could explain everything from Fukushima to Frankenfood, fake meat to Malaysia Airlines Flight 370.

As for the pervasively eponymous Pauli, the man who turned spooky correspondence into hard science: thirteen years after coming to Jung for treatment, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics.

On January 7, 2021, Jacob began his thirty-four-hour trek back to the desert, which proved uneventful except for a text message from his mother saying the FBI was looking for him. The farther he drove west, the more conscious he became that he was now famous—and that the police wanted to chat. He called the FBI’s Washington field office and confirmed that he was in fact the one who had sat in the chair of the president of the United States Senate, that Mike Pence was a child-trafficking traitor, and that he was the one who had left a note for the vice president promising that it was only a matter of time—justice was coming.

The agent on the other end of the line asked if he might swing by their offices in Phoenix to continue the interview, and Jacob was amenable. The next day, on his way to yet another protest at the Arizona State Capitol, he pulled his Hyundai into the parking lot on North Seventh Street, down the street from the Deer Valley Airport, home of the Phoenix Police Department’s citywide helicopter patrol operations.

Perhaps he was surprised when the FBI asked if they could search his car. Inside they found his buffalo horns; coyote-tail headdress; red, white, and blue face paint; a six-foot-long flagpole-spear; his white bullhorn; and a rubber mallet that according to Jacob just happened to be in the vehicle, and had no connection whatsoever with Thor’s hammer.

Unfortunately for Jacob, Mjollnir never made it to the Arizona State Capitol; neither did the ancient pagan god of thunder unleash his vaunted cosmic pyrokinesis on the feds or eviscerate the office building with one of his god-blasts, as the FBI cuffed him without incident.

On January 11, a federal grand jury indicted him on six counts—two felonies and four misdemeanors—and Jacob became one of the first insurrectionists to be arrested and charged. He faced twenty years of imprisonment, plus a fine of up to $250,000. Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram removed his accounts.

Within days, Jacob’s counsel reached out to the White House chief of staff, Mark Meadows, to request a presidential pardon. In the final days of his presidency, Donald Trump pardoned more than 150 people, including Roger Stone, Paul Manafort, Charles Kushner, and Lil Wayne, but not Jacob Angeli-Chansley, who eventually pleaded guilty, spent twenty-seven months behind bars, and a few weeks after early release found himself ordering organic pizza at Picazzo’s.

When at long last lunch landed on the table, he clasped his hands and prayed.

When he opened his eyes, I asked whether he was a Christian.

“No,” he said. “I am not.”

Then why the “thank you, Heavenly Father”—just as he had prayed on January 6?

“Father Sky,” he said. “Mother Earth.”

Eventually, the attractions of ancient hermetic wisdom reeled in the greatest rationalist of them all: Sir Isaac Newton. When his long-forgotten secret notebooks finally surfaced at auction in 1936 (some of which, oddly enough, were purchased by John Maynard Keynes), they revealed that beneath the sane world that he had laid bare by dint of cold reason lay something far beyond comprehension—that his numerical calculations were the merest shadow of his kabbalistic obsessions. The same man who had pierced nature’s hidden order and revealed the rainbow of colors encrypted within white light had devoted millions of words to topics including astrology, gematria, the cosmic significance of the number seven, and the philosopher’s stone. The extraordinary lengths to which he went to predict the date of the apocalypse were equal parts profound and preposterous.

And just as it would to Q and his Anons, the temptations of secret knowledge that had hooked Newton proved irresistible to the masses. By the middle of the eighteenth century, Europe and North America were teeming with alchemists. Writing half-baked verses about the divine powers of truth, beauty, gravity, and magnetism had become as fashionable as playing the clavichord. No less of a clear thinker than Benjamin Franklin would envisage the “inestimable Stone” that could cure “all Diseases, even old Age itself.” Counts and dukes spent fortunes purchasing laboratory equipment they hoped might enable them to distill the drug of endless vitality and virility—life from blood, feces, and urine—and, like the great Peter Thiel, stay young forever. The age of Locke and Voltaire is littered with victims of poison, electrocution, and asphyxiation.

As was to be expected, the search for higher consciousness eventually became an excuse for the elite to see and be seen. Eighteenth-century society ladies gathered at private parties to swoon as waves of “animal magnetism” enveloped their body and soul. When they escaped the city for country estates, they found pagan temples constructed in the grottoes and caves that dotted untamed English gardens, often inhabited by hired hermits paid to wear goatskins and instructed not to bathe or cut their hair or nails so that they might possess a look rather like Jacob’s on January 6, one that radiated wisdom born of meditation and solitude. After that frisson of primitivism, it was time to head inside to inhale some laughing gas—the invention of which soon followed the discovery of nitrous oxide. “I am sure the air in heaven must be this wonder-working gas of delight,” wrote England’s poet laureate Robert Southey.

Three centuries ago, then, a revolution in consciousness was at hand, yet the standard story of America’s founding remains stubbornly the same: a political revolution born at the height of the Age of Reason, a constitution written by sober Enlightenment philosophes grounded in the world of empirical fact, a country dedicated to the proposition that reason and reason alone would lead to a more perfect union of humans within a society.

There is plenty of support for this scenario. No doubt modern chemistry was bubbling up from the ancient stew of alchemy right around this time, and the mechanistic, self-limiting, evidence-based notion of truth could not help but oppose the older and more popularly embraced mystical, occult, almost völkisch notion of the truth—with each side declaring itself the truthiest truth of them all. While cosmic mysteries beckoned, a new breed of natural philosopher—the scientist—was quite content with the fact that some secrets might be beyond his purview. The French atheist Baron d’Holbach articulated a novel set of boundaries:

It is not given man to know everything, it is not given him to know his origins, it is not given him to penetrate to the essence of things or to go back to first principles.

D’Holbach believed that the universe was matter in motion, that there was no God, no miracles, no supernatural, no endless referential reticulation of cannabis, crystals, and kabbalah. But such a thoroughly disenchanted cosmos was but a fraction of the evolving cultural landscape. Marshaled against the new philosophy of science was a tradition led by a pantheon of Jacob’s intellectual forebears, from Paracelsus to Newton, Ludendorff, Jung, Leary, and Ram Dass.

With this intellectual lineage, conspiracy theorists are not about to back down from their truths, because their own scientific method possesses a historical claim as deeply entrenched as ours. And they have a point: their spooky correspondences, their spheres of influence, their invisible forces, their gravities and their magnetisms, their parsing of the invisible effluvia—without these, there never would have been any science at all. And that’s the reason reason has yet to dent the citadel of MAGA, and never will.

Like his solar-phallic fantasy father, who is able to stare down an eclipse without eye protection, Jacob plans to return to the Capitol. He has filed paperwork to run for Congress and represent Arizona’s Eighth District in the House of Representatives. If you rent a billboard for him, he promises to give you a personal call. Details at shamanforcongress.com.

Win or lose, there’s always branded retail. Since his release from federal custody, he’s variously hawked Shaman iPhone cases, Shaman stainless-steel water bottles, Shaman hats, and Shaman-brand mouse pads, not to mention T-shirts, socks, yoga mats, yoga pants, leggings, and slides. At one point, his online store, Forbidden Apparel, offered a rather ornate Shaman American flag featuring an image of Jacob in full regalia superimposed onto the Stars and Stripes, his mouth open mid-chant, his staff with stainless-steel finial gleaming like a bayonet. (The flag cost $44, but you could purchase the same design on a coffee mug for $17.) No beer cozies, but for those manifesting a presidential run, there were plenty of shaman 2024 bumper stickers.

He produces The Occult Apocalypse Show, available from Apple Podcasts. Recent topics of discussion include the Rosicrucians, Skull and Bones, and Judy Garland. As his brand metastasizes, Jacob has become a supermeme, portrayed by turns as an action figure, a Halloween costume, the Joker, and for Christmas Frosty the Shaman. On his educational website, forbiddentruthacademy.com, he appears as a god, staring down the phases of the moon.

He’s also available on Cameo.

“You’ve got to put yourself in the alchemical fire every day,” Jacob told me. “Hello ordeals and suffering. Hello enlightenment. Hello purity.”

We talked until his agent called and he had to go. But before he disappeared into the celestial fire of the Phoenix heat dome, I had to ask—what was his best-selling merch?

It was the coffee mugs.