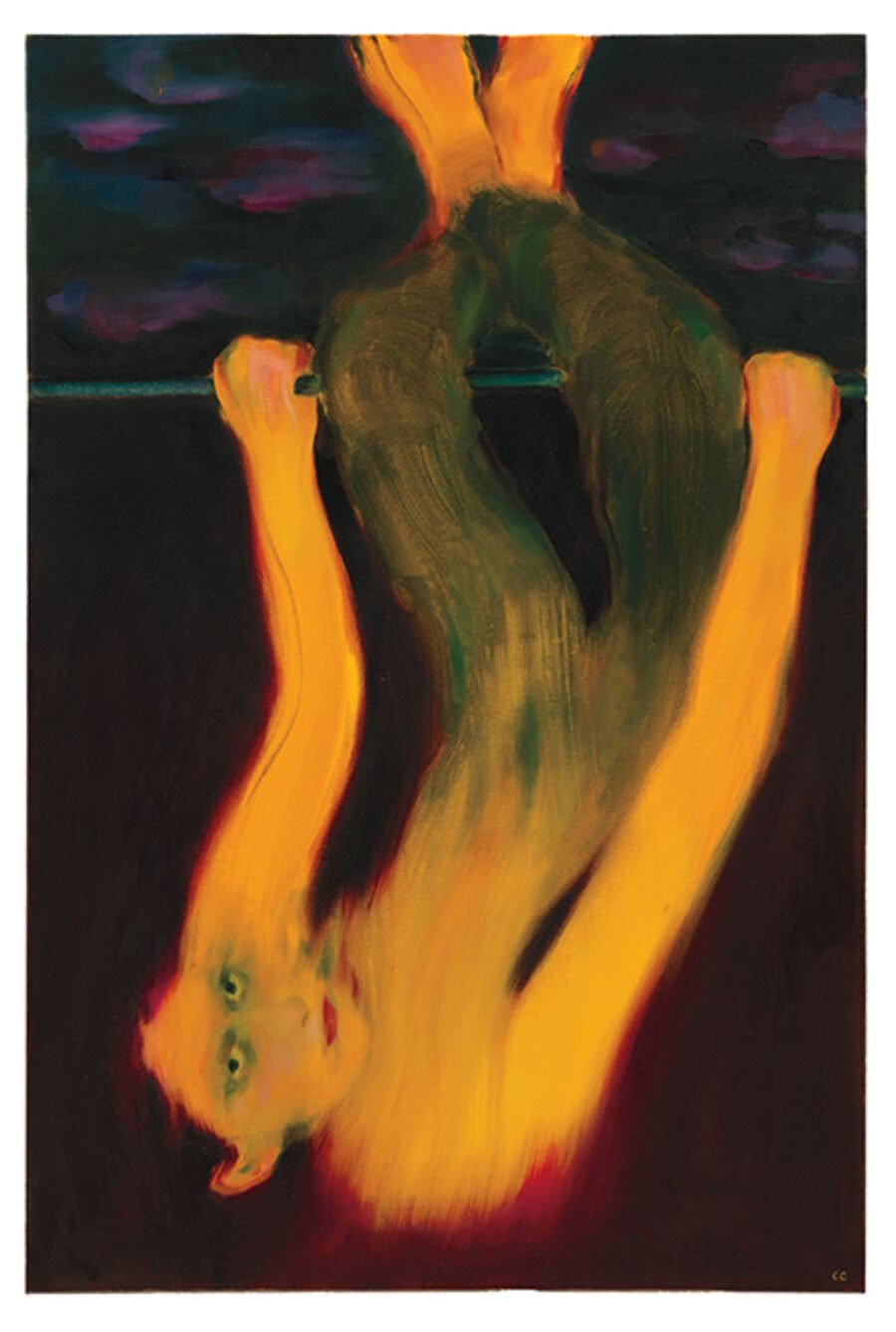

Thresholds, by Cathleen Clarke.

Courtesy the artist and Margot Samel, New York City

New Books

Because I’ve written about government conspiracies, I sometimes hear from crazy people. “Only the intervention of AI can stop Man from creating Hell cybernetically,” one wrote recently. “It would be better to have AI either remake us or end us as a species.” Tough, but fair. I read such screeds with great interest. Sometimes I’ll google my correspondents, looking for signs of their decline, the lives they led before illness consumed them. As a recreational drug user with a robust knowledge of the CIA’s mind-control program, I worry, a bit romantically (i.e., grandiosely), that I might join their ranks someday. Insanity captivates me, but only, of course, from afar. How easy it is to leer at the guy on Instagram who claims that the “Satellite Men” have been “damaging my teeth for over twenty-two years.” And how easy it would be, were I to encounter him on the street, to walk briskly, urgently away.

Would I still be able to face someone like that if I couldn’t gawk at or ignore him—if he were inescapably close? In The Complications: On Going Insane in America (HarperOne, $29.99), Emmett Rensin reflects on the ironies and humiliations of losing one’s mind in a nation that dehumanizes even its “normal” citizens. In an aside, he writes of Malcoum Tate, a schizophrenic man whose sister shot him dead on the side of the road after he went off his meds and threatened to kill his infant niece. “It’s a sad story, but if Malcoum Tate had lived, he’d just be another pain in the ass, wearing out the patience of his friends and family,” Rensin writes, “another frightening lunatic tolerated from a distance.” He can talk this way because he’s a lunatic, too, tired of seeing his condition treated with kid gloves. Efforts to destigmatize mental illness, well-intentioned though they may be, have brought relief neither to the insane nor to those charged with their care, Rensin believes. They are academic exercises, more concerned with doctrinaire politesse (don’t call them nuts; call them biopsychosocialpoliticalbodymind impaired) than with solutions. “I do not suffer mainly from stigma. I suffer from blunted affect and pressured speech, delusions of reference and violent moods and diminishing cognitive function,” he writes. “I am not mainly invested in being Accepted as Valid, but in staying well enough to stay free and employed.”

Rensin, now in his thirties, was eight when he first noticed fissures in his psychology. He feared a colony of ants would pour from the showerhead and suffocate him, “swishing under my tongue” and “cascading down my windpipe.” Since then, he’s threatened suicide; punched his best friend in the face; attempted to carve out one of his lymph nodes with a butter knife; crashed his car under direct orders from God; hidden in the closet from the withering gaze of his cat; broken into the home of a near-stranger to recover a lost scarf; and become convinced that his roommate was observing him on a series of monitors, a conceit not dissimilar to that of the movie Sliver. He once wore the same pair of black jeans for months, so I trust him when he says he stinks. The voices in his head sometimes sound “like the din of background chatter in a restaurant run through a ham radio,” and at his worst, he feels like a figment of other people’s imaginations. But his symptoms most often present as those of a run-of-the-mill asshole, which is what everyone seemed to assume he was at first. “The problem with teenage boys,” an early therapist told him, “is that no matter what’s wrong with them … they’re sullen and pissed off all of the time.”

About those therapists: He’s burned through some two dozen of them over the years, and he wouldn’t wish their hours of talk on anyone, especially anyone sane. “I go because I have to,” he writes. “But the sort of person who goes because they want to is the real lunatic, the real victim of some hitherto undetected personality disorder.” Psychiatry hastily slotted him into its strict taxonomy. He was reduced first to a series of data points and then a line of best fit. His official diagnosis began as “bipolar disorder type one, rapid cycling with mixed episodes and associated psychosis”; another shrink revised it to schizoaffective disorder, which has a history of poor diagnostic reliability. Rensin was dismayed to learn that some doctors saw it as “a lazy bucket diagnosis for overworked clinicians.” On the plus side, those clinicians granted him access to the antipsychotic armamentarium (his girlfriend, when he moved in with her, allotted a whole shelf for his medication). Swaddled in Seroquel, Abilify, and Ativan, he became functional—until he goes on the lam and has to be hospitalized. After one such incident, in Iowa, he received some routine paperwork: “It looks like you’ve been having hallucinations and/or delusions. But a normal life is possible!”

Hostile to the medical establishment and its many discontents, Rensin has suffered the misfortune of being insane at a time when the condition—its meaning, its meaninglessness—is assailed from more sides than ever, “a new species of identity to be recognized and protected and milked for New Voices.” Disorders like his are now manageable, but no more tolerable for it. Part of an unwilling coalition of “mad memoirists,” Rensin knows he’ll be accepted only insofar as he attains “a state of permanent infantile respectability mongering” by dressing up a graceless disease that makes him unbearable to be around. What he really wants is to ditch all pretense of enlightenment:

I miss when I was lost…. I feel one foot in the world of floating thoughts and brain murmurs and sea ships and prophets and God, and another foot in this world, where even drugged and therapized, I am not a good or useful person…. I want to fall backward, to let go of the medication and the insight and the slow push through thick sludge.

I’m compelled to wish him the best, but I don’t know what that looks like for him, and he doesn’t, either. His book is caustic and incisive, never more so than when his readers, curled up neurotypically on our couches, are in his sights: “You want to know what madness feels like. Why do you believe that I could tell you?”

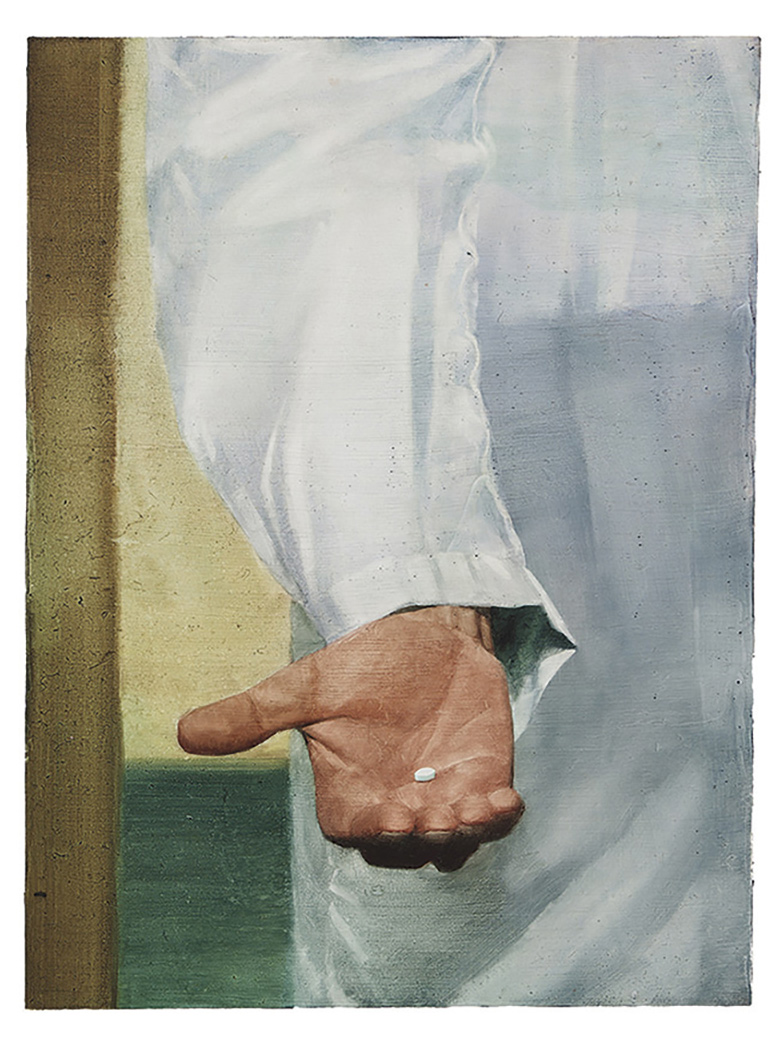

Freedom from Want, by Joseph Yaeger

© The artist. Collection of Alexander V. Petalas

Convinced that there was “some weird stuff” in his neck, Rensin sought the advice of a doctor, who told him, “Yeah, there’s all kinds of weird stuff in there. Don’t press too hard.” Case closed. A Body Made of Glass: A Cultural History of Hypochondria (Ecco, $29.99) finds Caroline Crampton pressing too hard on a similar area, “two square inches of skin on my neck to the left of my Adam’s apple,” where weirdness abounds. As a teenager, she had a relatively rare tumor there that made “a clicking sound I could hear with my tongue.” It’s long gone now, but you never can tell with tumors. So she probes. She palpates. Her neck ignites “into quivering sensation” at no provocation. “You know it’s not real,” she tells herself, “but this time it might be.”

Since her cancer treatment, Crampton has found herself irretrievably fragile, or irretrievably aware of her fragility: tantamount to the same thing, she points out. Every ache marks the return of an existential threat. Her body is like one of those miscalibrated car alarms that blares whenever a truck drives by; it makes terror just by acting terrified. She cannot accept that “my billions of cells do not work to my command or even for my attention.” The stress of coping with so many unreal diseases has a way of creating real ones. Her hair falls out in clumps, and she goes periodically deaf and blind.

Crampton is a hypochondriac: her preferred term, though modern medicine is trying to drum it out of the discourse. The DSM-5 now prefers “illness anxiety disorder” and “somatic symptom disorder.” Sufferers of the former, the manual notes, “research their suspected disease excessively (e.g., on the Internet)”—a parenthetical so stupefyingly obvious that it seems a scathing indictment of psychiatry, something out of Rensin’s book. Crampton, also like Rensin, finds that she can’t pour herself into the DSM’s diagnostic molds. There’s no Sturm und Drang in illness anxiety disorder, but hypochondria, she finds, offers a rich and nebulous tradition, binding her to two millennia of people led around in circles by their own bodies.

Originally described as ambiguous illnesses of the abdomen, hypochondria had evolved by the eighteenth century into a nervous disorder, a disease of civilization. As the physician George Cheyne put it, nervous maladies affected those “who fare daintily and live voluptuously,” those who had only themselves to blame: “it is the miserable Man himself that creates his Miseries, and begets his Torture.” An engraving in an edition of Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy depicts the Hypocondriacus character, a prosperous man in a fur-lined robe who, looking impassive and empty, contemplates “the profusion of medicine bottles and unraveling recipe scrolls around him.”

Contemporary hypochondria, Crampton says, also bears a kinship to a rare delusion from medieval and early modern Europe, when, at the same time that certain forms of glass became more popular, some people in the nobility came to believe they were made of it. Today, too, the health-obsessed feel vitreous and brittle, yearning for total transparency. The present vogue for full-body MRI scans (a practice touted by Kim Kardashian) speaks to a desire to see through oneself—a desire only within reach for the ultrarich, who treat preventive health as a fashion, who advertise, in essence, that they have achieved glassiness, that they’ve peered through their own flesh and into the future.

Crampton lives in the United Kingdom, so the battery of tests is hers for the taking, with the NHS footing the bill. Neurological, cardiological, endocrinological—she’s never met an exam she didn’t want. If no news is good news, then why not get no news as often as possible? At the nadir of her hypochondria, Crampton “became a shadow person who existed only to be pricked, scanned and quantified.” Her dedication turned an intensive urine sample into performance art:

I collected all of my urine for forty-eight hours in a giant vat so heavy that I had to strap it to the front of my bicycle and wheel it along the pavement so that I could drop it off awkwardly at the clinic reception.

What does she get for her troubles? A letter saying that a screening has revealed “something worthy of further investigation,” and, in the place where further resources should have been listed, some forgotten placeholder text: “<insert helpline number here>.” Her health was fine, in the end, but there should be no surprise that a world with “<insert helpline number here>” is also a world where we make doctors out of search engines; where we pay for Zeebo-brand “honest placebo pills” because it still feels healthy to be taking something, even if that something is nothing; where we are “prostrate before the machine, begging it for knowledge.”

Crampton found the onset of the pandemic “oddly calming,” which is how you know she’s mentally ill. Disinfection became ritual, hypochondria was exalted as hygiene, and hypochondriacs “were no longer the outliers, with our irrational fears and our imaginary illnesses.” Doctors saw an uptick in teenage girls with Tourette’s syndrome: twitching, cursing, bruising themselves, they’d blurt out “beans!” in a British accent when they knew perfectly well they were from Chicago or wherever. It turned out they were parroting Tourette’s influencers they’d seen on TikTok. Pent up at home, they sensed something was wrong, so they made something wrong. They were “carefully studied and validated by experts,” Crampton writes, sounding slightly envious. “Look at us, they seem to say. We are not OK, and neither are you.”

The Blue Bed, c. 1900, by Walter Gay. Courtesy Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, House Collection, Washington

What would the DSM-5 make of Henry Ward Beecher, then? My best guess is narcissistic personality disorder, with some exhibitionist tendencies thrown in. As the celebrity pastor of Brooklyn’s Congregationalist Plymouth Church, Beecher suggested somewhat radically—and perhaps flimsily, from a theological perspective—that it was possible to follow Jesus and enjoy oneself at the same time. This was in the mid-nineteenth century, so he pretty well blew people’s minds. Thousands came to hear his “Sabbath harlequinades,” as Vanity Fair called them, and to see the church’s lavish flowers, its piano and organ, and its altar furniture of “olive wood from the garden of Gethsemane.” He promised “love without stint,” and he gave it, seducing some of his flock and embroiling himself in scandal, his era’s spiciest.

Lib Tilton, a devout churchgoer and the wife of one of Beecher’s close friends, confessed in 1870 that she and her pastor had practiced “nest-hiding” together. That’s when you make your bed and then lie about it. Beecher supposedly believed himself “on the brink of a moral Niagara” and swore that he’d offered Tilton “unstudied affection,” but never sex. Robert Shaplen, a late staff writer for The New Yorker, says in Free Love: The Story of a Great American Scandal (McNally Editions, $18) that the six-month Beecher–Tilton trial was “a great passion drama,” raising “mere name-calling and character-destruction” to “high literary and elocutionary levels.” The prosecution lambasted Beecher for his “insidious and silver tongue which would lure an angel from its paradise,” while the defense held that “so flagrant and heinous an imputation” could bloom only “where the wicked classes make their meetings, and hold their gossips with a sneer and a smile.” Free Love came out in 1954, and it’s fun to view this much older affair through the lens of Shaplen’s durable midcentury elegance—looking back in time twice.

And yet we may as well be in the present. Some of the pleasure in sex-scandal watching comes from its undying steadiness. It’s a genre. It has rules. Like a Trump or a Depp, Beecher’s “new aura of sin now made him a stronger attraction than ever,” Shaplen writes. Beecher–Tilton looks a lot like Clinton–Lewinsky, too, right down to its principal’s deployment of the phrase “that woman.” Both cases generated a certain slobbering shorthand: the Cigar and the Blue Dress were, for Beecher, the Ragged Edge Letter and the Pistol Incident. If there’s insanity here, it may well be on the part of the hungry crowd, a mass delusion that our observation is morally necessary; that dissecting a private act between two people is a spectator sport; that we aren’t watching porn. Something more always seems to hang in the balance, as if we might grasp the nature of all deviance if only we looked closely enough.

I want Rensin to tell me what madness feels like; he can’t. I want Beecher to have owned up to his hypocrisy, as if something would’ve come of it; he didn’t, and it wouldn’t have. To be sure, Shaplen knows how to draw the preacher and his cohort into the currents of their time. The trial touched on suffragists, spiritualists, phrenologists, and marriage reformers; it enthralled the public in part because it was primed to adjudicate the direction of society, our openness, the reasons for our lovemaking. It ended with a hung jury.